Because of her chronic illness, artist Poppy Nash has developed a complicated love/hate relationship with her bed. Here she explores how a medieval manuscript was her starting point for a recent bed-inspired artwork that celebrates the everyday nature of illness.

My bed represents both a space of comfort and confinement. It is somewhere I can retreat to when I want to cocoon myself from the world – it can be a refuge. But due to my chronic illness, I sometimes can’t get out of bed and I grow to resent it. It becomes my prison.

I have expressed my experience as a type 1 diabetic through textiles because of the significance of beds and health in my life. For a project titled ‘12/7 Tripping’, I imprinted bed sheets and blankets with the constant and relentless calculations that I need to make to manage my diabetes. Worrying about this does not stop when I go to sleep – it is always there with me, and diabetes often disrupts my sleep. Instead of relaxing in bed, I can often be left sweating with anxiety.

I have thought a lot about what our beds mean to us. We spend so many crucial moments of our lives there – we are usually born in a bed and die in one too. You do a lot of things in your bed. It is safe. But it is also scary. Sometimes you can’t get out of bed. I have had to spend hours and days both in my own bed and in hospital beds, which I have hated. How can you love and hate your bed?

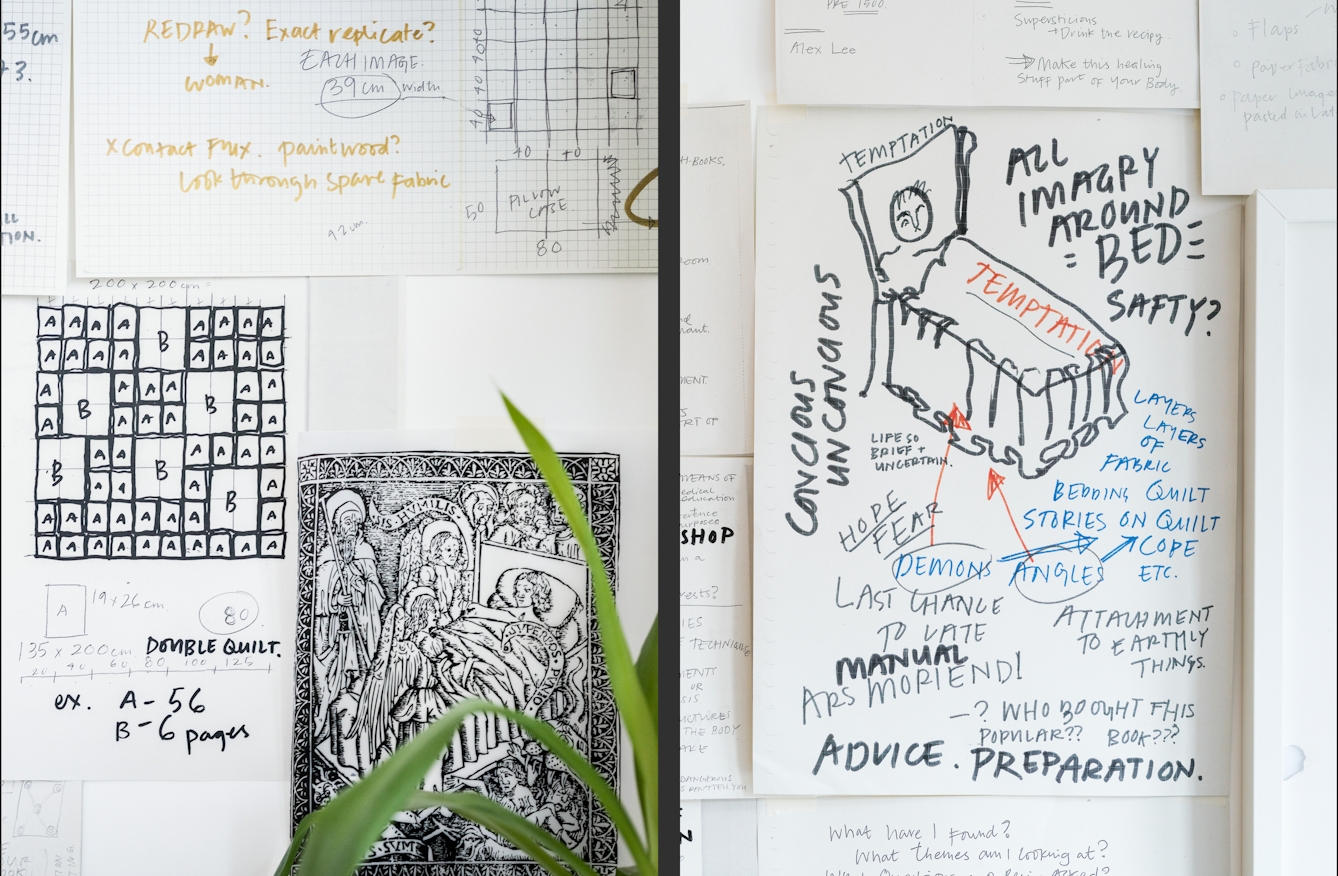

Poppy at home with her research material.

Exploring medieval sickness and health

A research grant to look at medieval medicine provided me with the opportunity to explore health and illness as inspiration for my art. This included my interest in the role beds play in our lives.

It was fascinating and emotional to look at these manuscripts about health. When I saw my first manuscript I could have cried. I didn’t expect that, but it was so old and held so much as an object. I imagined all the hands that had touched the information held in that manuscript.

One manuscript had advice to help with childbirth – imagine giving birth at home and all you had was handwritten knowledge. I’m terrified of having a baby even now, and we know so much. There was one part that was covered in blood, which was very exciting, because stains are clues, and this made me picture someone using the manuscript during childbirth. I never thought I would get excited about an old stain!

There was one part that was covered in blood, which was very exciting, because stains are clues.

The more you look through books and manuscripts, the more stories you are left to imagine. I wanted to find out more about the people recorded in the Bills of Mortality, weekly listings – in London parishes during plague outbreaks – of those who had been buried, and what they’d died of.

Poppy's research

Through my research, I encountered the ‘Ars moriendi’, an early 16th-century printed manual about preparing for death.

The woodcuts featured a dying man propped up in bed, surrounded by various temptations.

My reaction to this book was to create my very own version.

I had never spent so much time thinking that, until recent decades, you simply died if you were ill. As a diabetic I would have died. There was no one like me who experienced the lived trauma of being both healthy and sick at the same time. There were no healthily sick people.

Through my research, I encountered the ‘Ars moriendi’, an early 16th-century printed manual about preparing for death. The woodcuts in it featured a dying man propped up in bed, surrounded by various temptations. When I saw these I believed I knew how he felt, and I needed to know why this book was filled with these images.

‘Ars moriendi’, which translates as ‘The Art of Dying’, explains how to ‘die well’ by providing practical advice and guidance. As I delved further into my research, I found that during these years written works were intended for men. So in these manuscripts we are following the stories of men.

How could I find out more about women’s history during the medieval era? I discovered that women’s stories were usually told through textiles and passed down through generations. We can also find information about women by examining their bones. I found this very engaging – women’s narratives are told through textiles and death.

My version of ‘The Art of Dying’

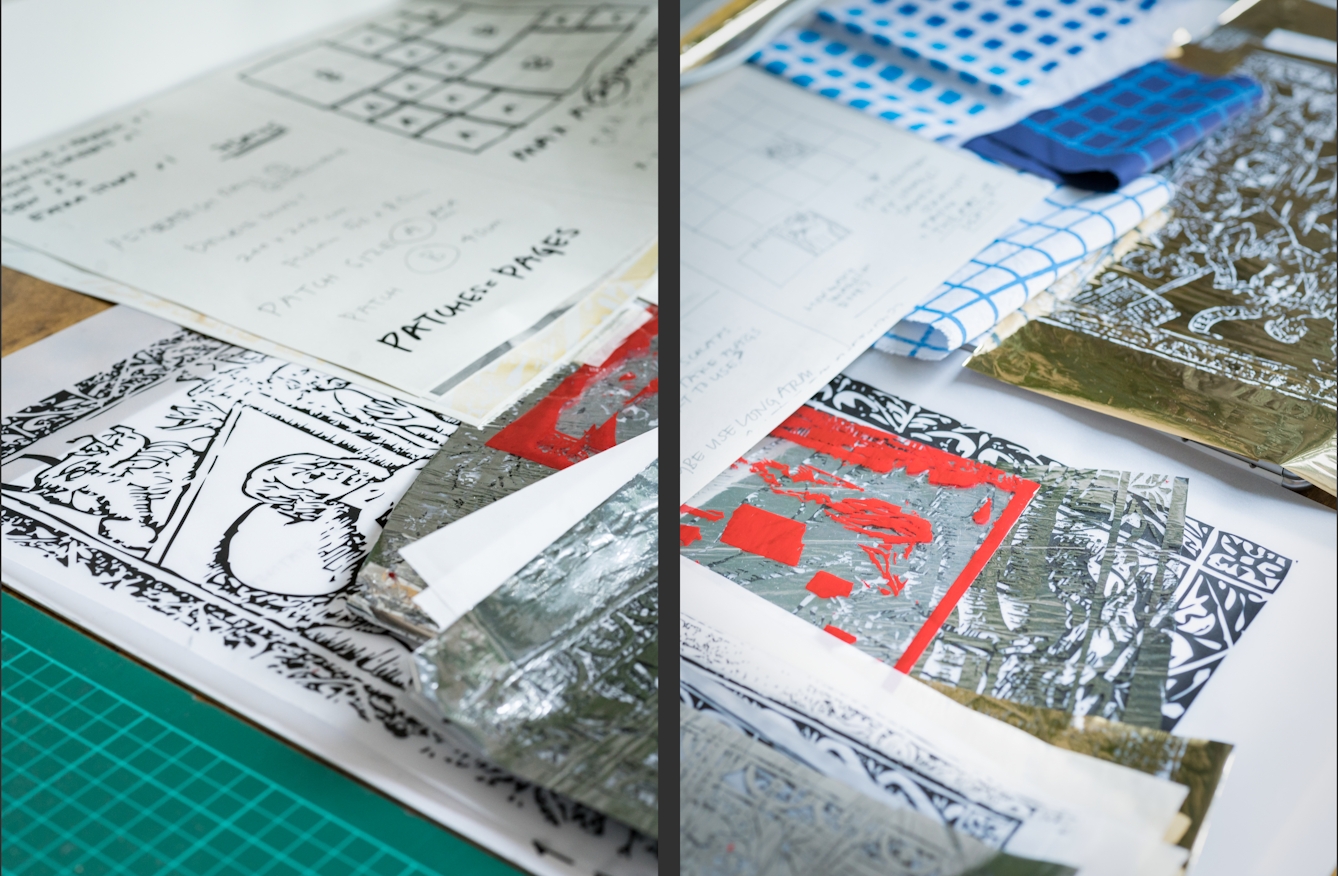

My reaction to this book, which I had accidently fallen in love with, was to create my very own version: a version for women. I named it ‘EPB/A/61997’, which is the shelf mark of ‘Ars moriendi’ at the Wellcome Library. I decided mine would be a duvet cover featuring images from ‘Ars moriendi’. A patchwork of golden images to sleep in and let sink into your subconscious.

Poppy's artwork

I decided to create a duvet cover featuring images from ‘Ars moriendi’. A patchwork of golden images to sleep in and let sink into your subconscious.

I made the quilt by hand, using screen-printing techniques.

Much of it is golden, using two different techniques to incorporate the gold.

The quilt represents our biggest fears and our connection to worldly things.

I made the quilt by hand, using screen-printing techniques. Much of it is golden, as I wanted this everyday quilt to be a celebration of everyday life. I used two different techniques to incorporate the gold: one was to push ink that has little flecks of gold in it through the screen; and the other was printing with glue and then adding golden foil squashed through a heated press. I wanted it to be printed on recycled material to reflect the way that medieval books often reused materials.

The quilt is now on holiday at Wellcome Collection before it comes home to live with me, where I will use it as a bedcover. I particularly like the idea of it having a life and journey of its own and being in the company of many different people. This is like some of the books I wanted to see during my research, which were on trips around the world, loaned to exhibitions overseas, where many different people could see them.

For me, the quilt represents our biggest fears and our connection to worldly things. It reminds me that none of us are going to get out alive, but that’s okay.

Poppy's research was part of a collaboration between Outside In and the Wellcome Collection.

About the contributors

Poppy Nash

Poppy Nash is a textile designer living and working in Glasgow. She creates designs, translates them into cloth, and uses these printed cloths to tell stories, both her own and other people’s. Her recent work has explored the connections between her chronic illness and her relationship with her bed. You can find her on Instagram.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.