The story of medicine in India is rich and complex: shaped by unique challenges and opportunities, and uniting cutting-edge technology with ancient cultural traditions. In her book, In the Bonesetter’s Waiting Room, Aarathi Prasad investigates how Indian medicine came to be the way it is. In this extract she travels to Kerala to explore Ayurveda.

Ayurveda: Knowledge for long life

Words by Aarathi Prasadaverage reading time 14 minutes

- Book extract

South of Mumbai, the skyscrapers of the city are soon replaced by verdant mountains and then lithe coconut palms which frame the sea and envelop the land. As the Konkan route exits Maharashtra, it runs past the modest homes, churches, mosques and forests of three more states – Goa, Karnataka and finally, Kerala. The two-day drive is undeniably beautiful and opens a window onto an India very different from the traffic-clogged, unrelenting urban sprawl of Mumbai. Much like the rich blue of the sky, shades of green on the ground are a welcome respite to the eye and a delight to the lungs. The Ghat mountain range that flanks India’s western coast ranks seventh in the world’s biodiversity hotspots, and along it the variety of plant life flourishing in this part of India becomes apparent. Among the prolific coconut palms are mango trees and cashews; Flame of the Forest trees crowned with mushroom clouds of crimson; emerald expanses of rice paddies; grand jackfruit trees, heavy with enormous, reptilian-skinned dark green fruit and with their trunks masked entirely by black pepper vines.

This chromolithograph from 1885 shows a flowering and fruiting branch of a cashew nut tree.

Such plants have been used in Indian medical traditions for thousands of years, and in particular by Ayurveda. I was making the journey to discover more about the use of herbs in one of India’s oldest native medical practices – and how the ancient discipline was faring against mainstream medicine. I knew that Western doctors had been studying and working with Ayurveda much longer than many suppose: in fact, the trade in the precious ‘black gold’ from the pepper vines and other medicinal spices I had seen was one of the great draws for 15th-century Europeans seeking out medicines, as well as exotic flavours. The lure of these valuable substances would also bring them into contact with a natural world largely unknown and mysterious, as well as diseases such as cholera and dysentery that they had never encountered before.

The medicine practiced in Europe at the time was based on a very different system from that of today. Medical knowledge in Europe during the Early Modern period was based on the 2,000-year-old tradition influenced by the writings of Hippocrates, Aristotle, Galen and Avicenna. According to their classical medical theories, it was imbalances in the four humours – blood (hot and wet), phlegm (cold and wet), black bile (cold and dry), yellow bile (hot and dry) – that were the cause of fevers and disease, and they were remedied through diet, purges, bleeding and plant and mineral-derived remedies. The concept of balance restoring health and imbalance undermining it would have been familiar in Asia and one upon which much of India’s folk and scholarly medical theory was also based. Many of these ideas were recorded in core Indian medical texts like the Sushruta and Charaka Samhitas dating between the ninth and sixth centuries BCE (and lost books it refers to, like the Atreya, and Agnivesa treatises). But they were also rooted in key ‘books’ of the Hindu scriptures – the Rigveda and Atharvaveda – which preceded these medical texts by around a thousand years.

In pictures

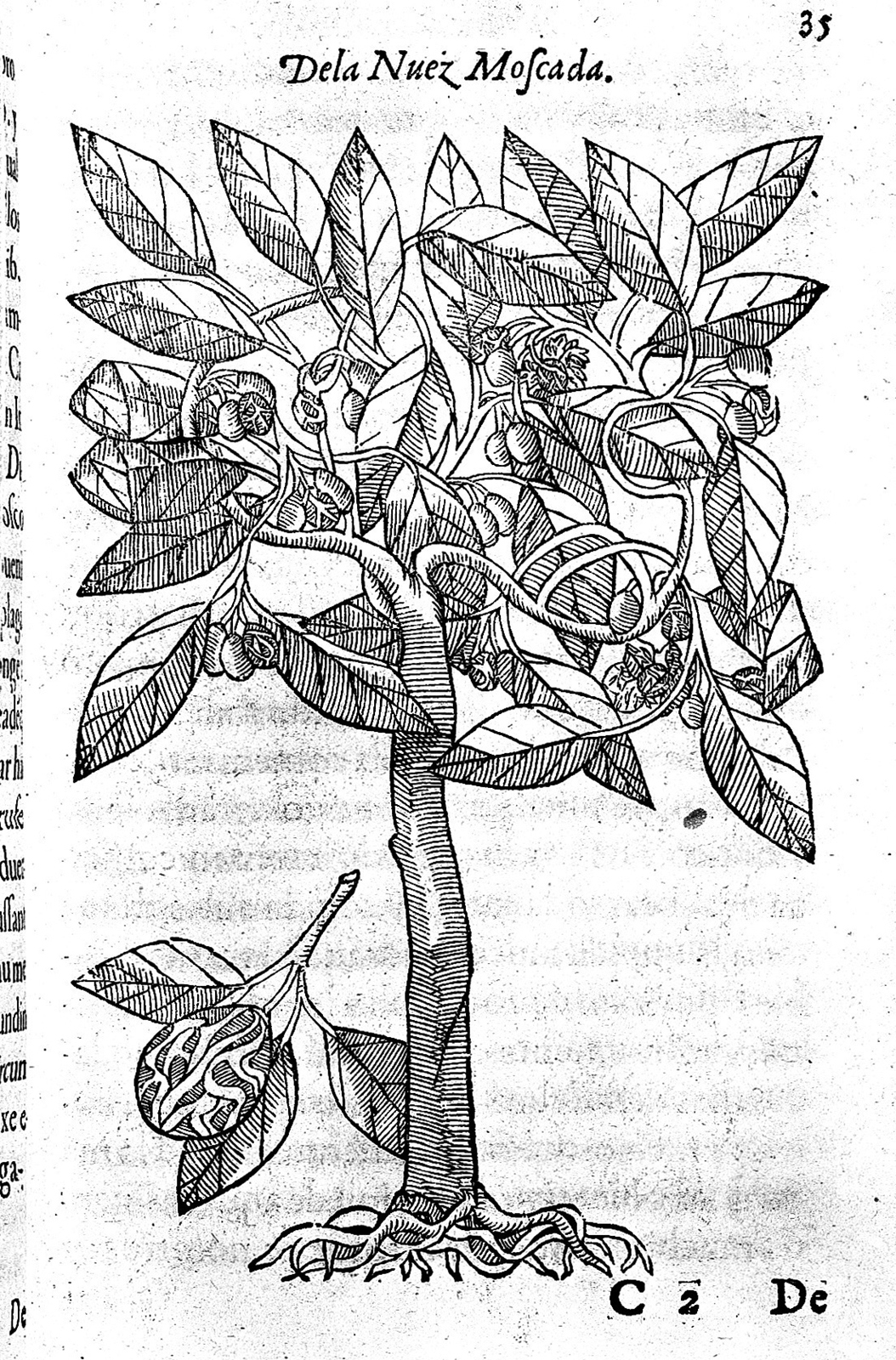

This image of a fruiting nutmeg tree appeared in a Spanish treaty of drugs and medicines of the East Indies dating from 1578, which you'll find in our library.

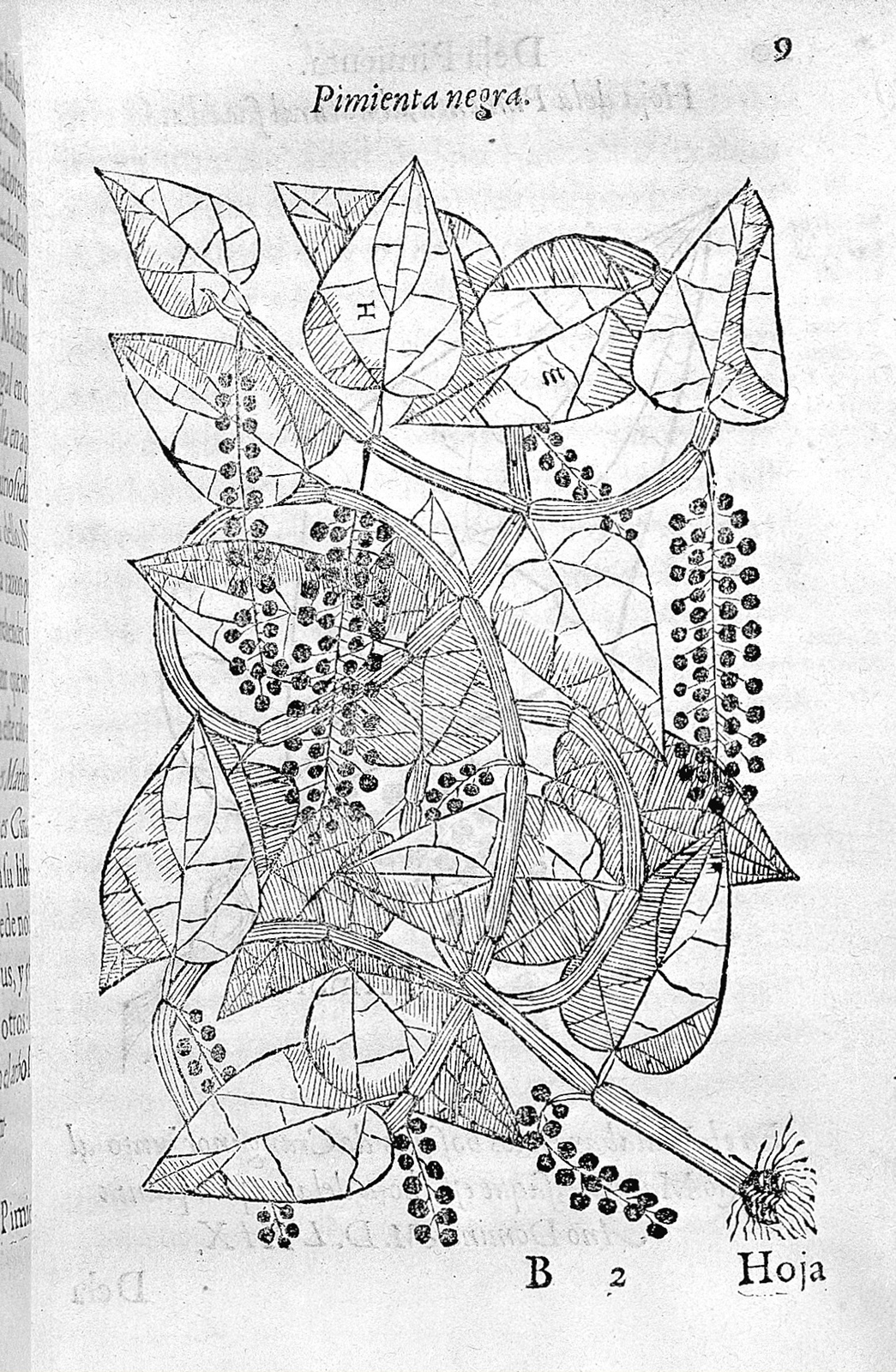

The trade in the precious ‘black gold’ from pepper vines and other medicinal spices was one of the great draws for 15th-century Europeans seeking out medicines, as well as exotic flavours.

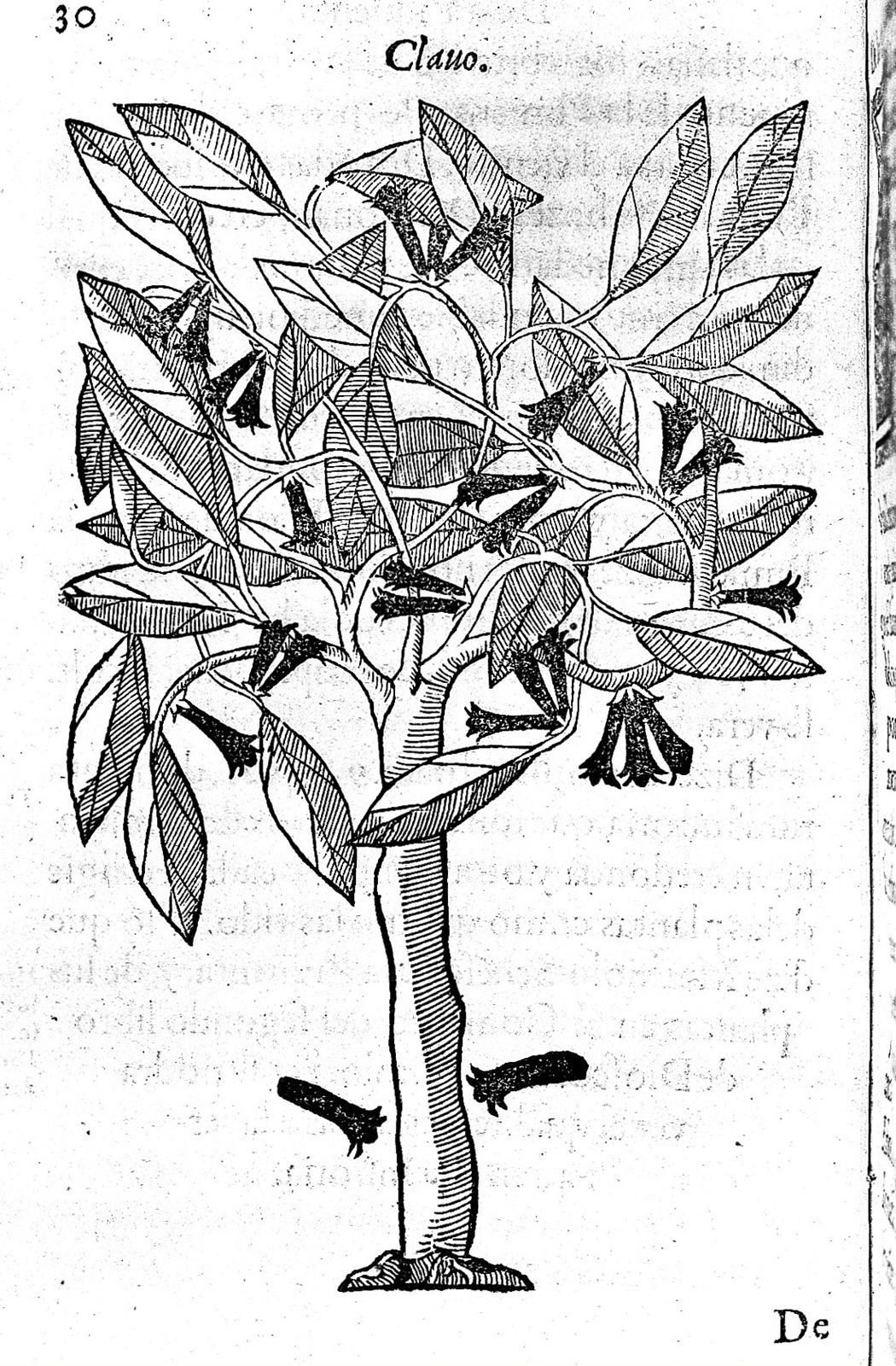

From the same 1578 book, this image shows a clove tree.

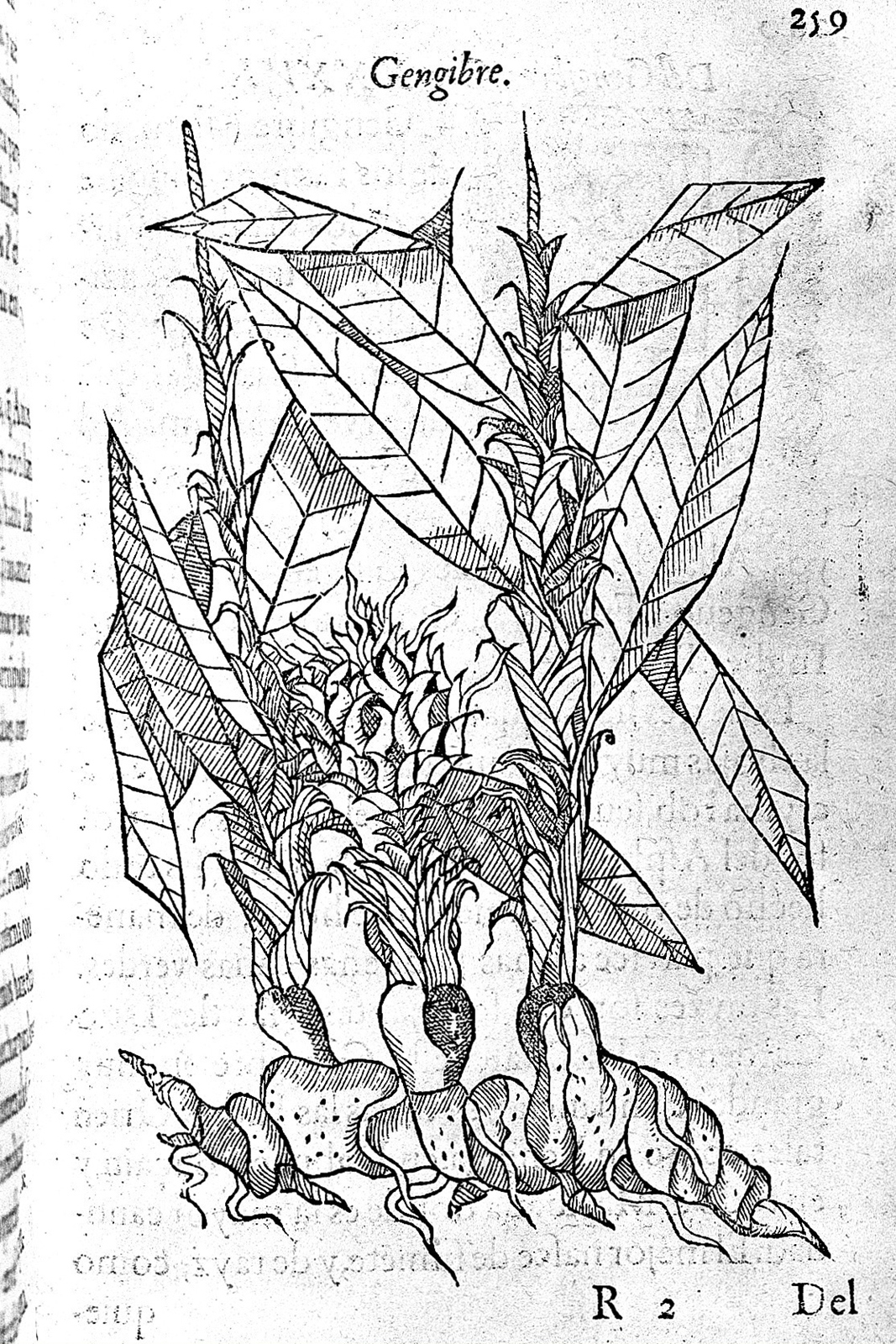

Ginger.

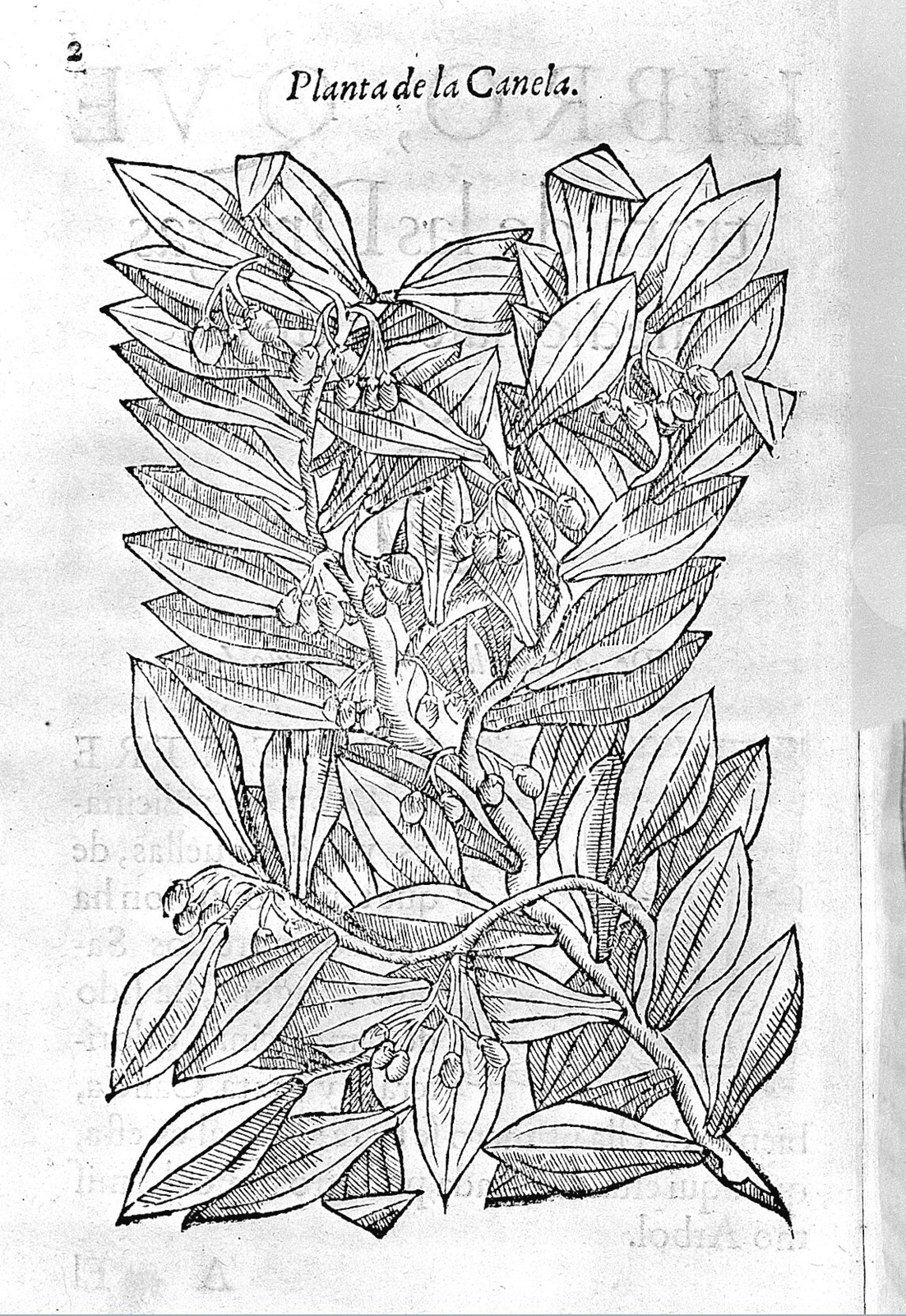

Cinnamon.

On 12 March 1534 a young doctor from a Portuguese Jewish family boarded a ship at Lisbon, bound for the west coast of India. It is likely that Garcia de Orta, who had been forcibly converted to Christianity under the reign of terror of the Spanish Inquisition, chose to escape persecution by taking a job 4,500 nautical miles away, as attendant physician to his military patron, Martim Afonso de Sousa, who had also commanded the first official Portuguese expedition to Brazil. De Orta served de Sousa during campaigns from the Kathiawar peninsula north of Mumbai, along the Arabian Sea to the south-eastern tip of India and into Sri Lanka.

From the age of 15 until he left Iberia at 34, Garcia de Orta had studied and then lectured in medicine and natural and moral philosophy. As his captain general’s military campaigns ended, he settled in Goa and set up a lucrative medical practice that he would oversee until his death thirty years later. As well as working as a doctor, de Orta dedicated himself to recording the use of more than eighty drugs, fruits, spices, minerals and medicinal preparations either found in India or employed there. He was clearly fascinated by the ancient and sophisticated medicines he had found in the subcontinent, planting botanical gardens both at his home in Goa and on his estate in Mumbai – very close to where the British-built Mumbai town hall stands today. He had agents – shopkeepers, traders, soldiers, translators, travellers, missionaries – send him plants and seeds from around India and he gathered information from discussions with Indian physicians, slaves, servant boys, cooks and gardeners. The information he collected was published in 1563 as Colloquies on the Simples and Drugs of India and it provided the Western and Eastern worlds with an early opportunity to explore the interaction both between old and new forms of knowledge and between Indian and European medical systems.

In India, both Portuguese migrants and Indian aristocracy came to de Orta suffering from conditions he would never have encountered in his own country. Undaunted, he adapted to his new practice: using taste and smell, he deduced what balancing properties – cold, hot, dry or wet – his new collections of herbs, seeds and drugs might have and prescribed accordingly. He experimented both on his patients and on himself, turning to Indian medical practices when his European methods failed and making their medicinal herbs famous among Westerners in India as well as back in Europe. By the time Goa’s Royal Hospital opened in the sixteenth century, both Indian physicians and folk healers were working alongside European doctors. The hybrid medical knowledge established there was enormously successful, and being adopted by the Portuguese seaborne empire, had spread to the hospitals of Lisbon and Coimbra by the 18th century.

In pictures

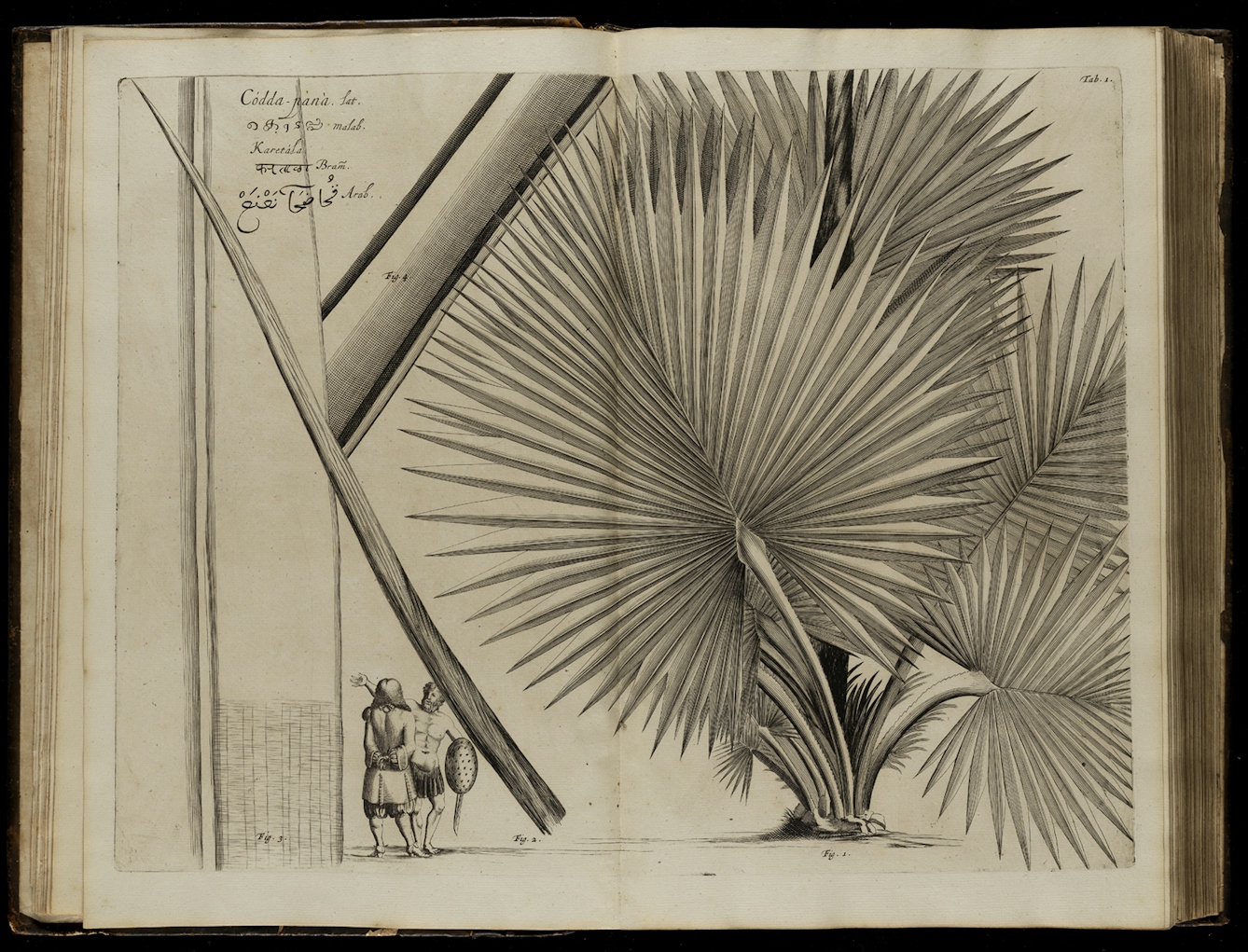

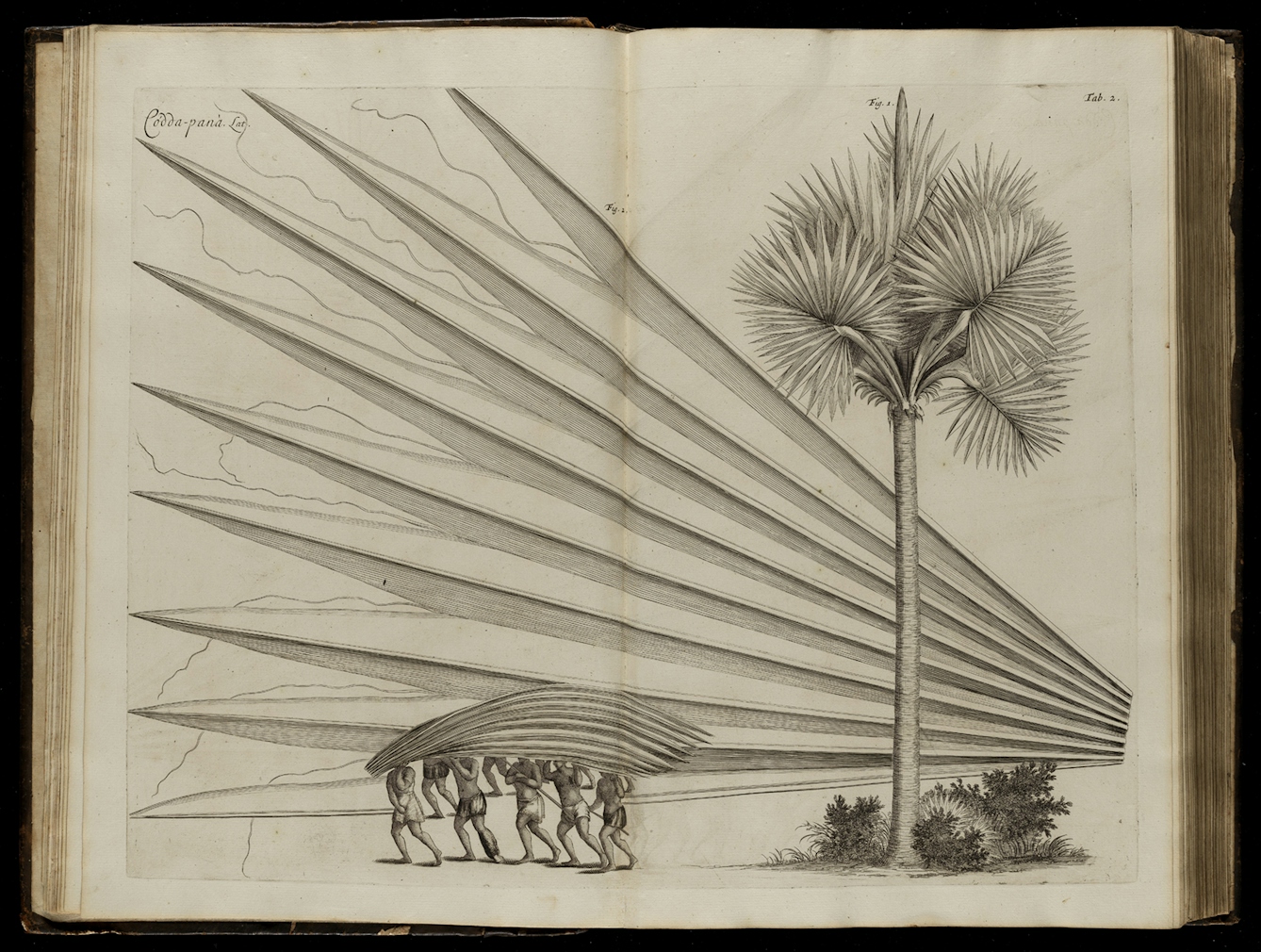

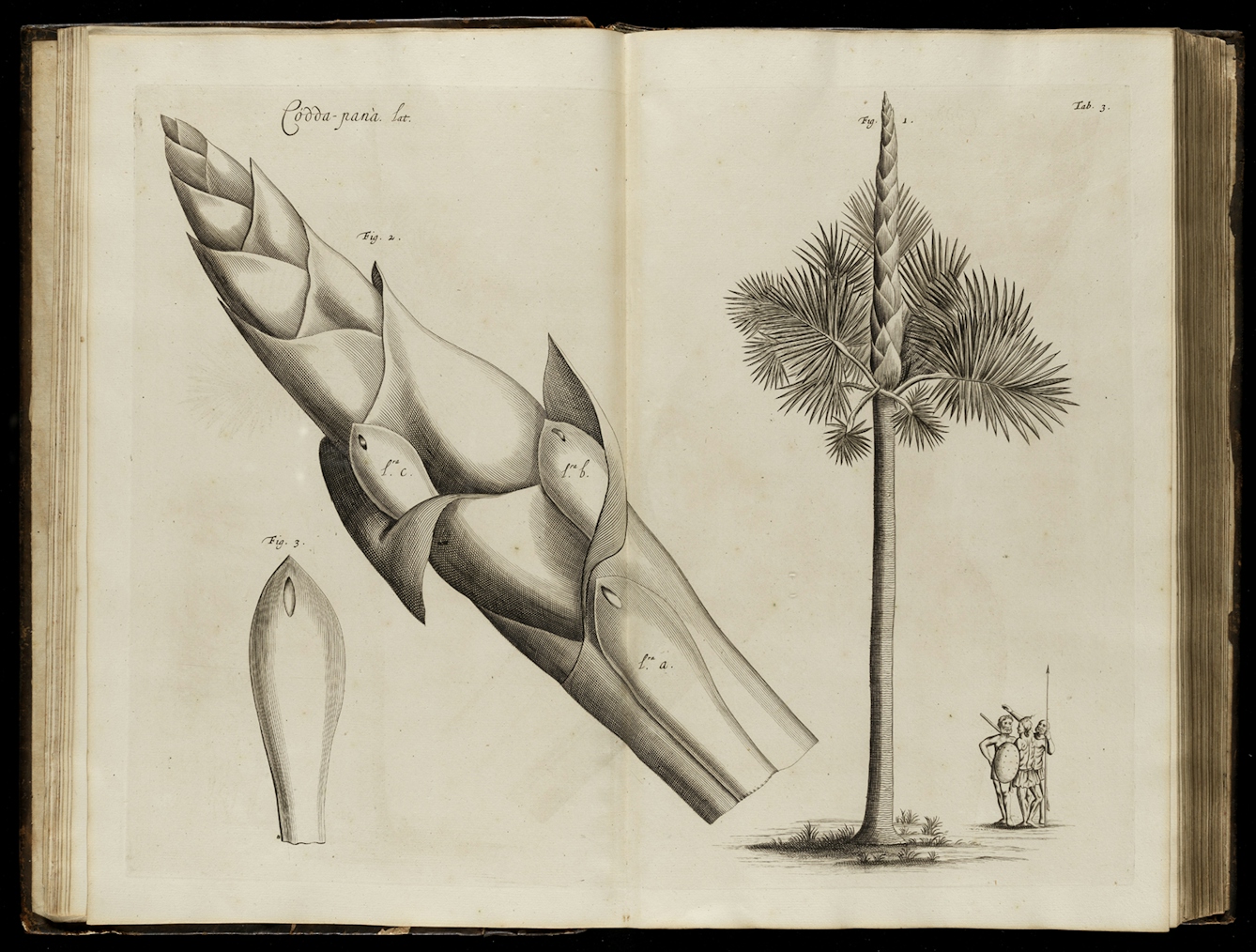

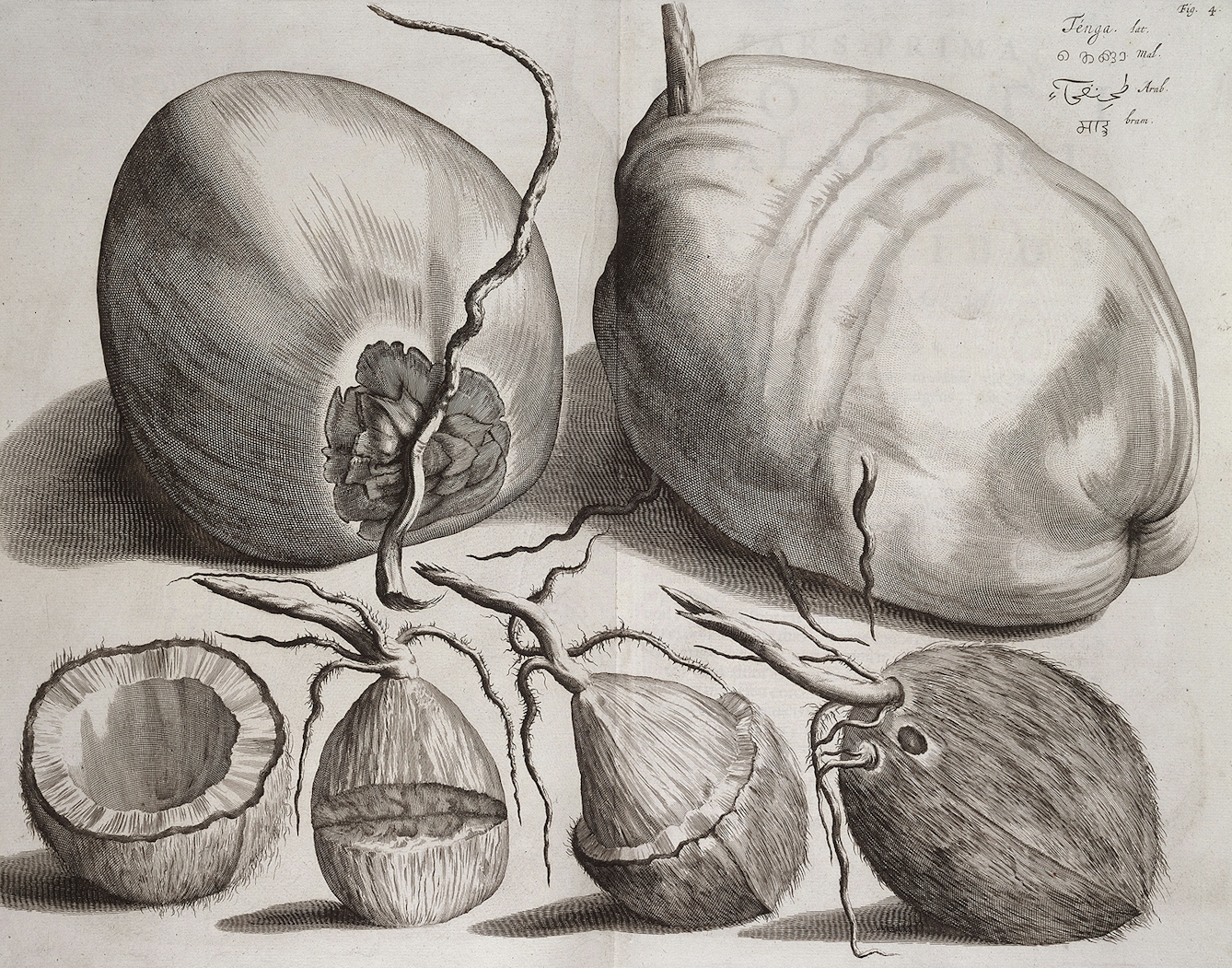

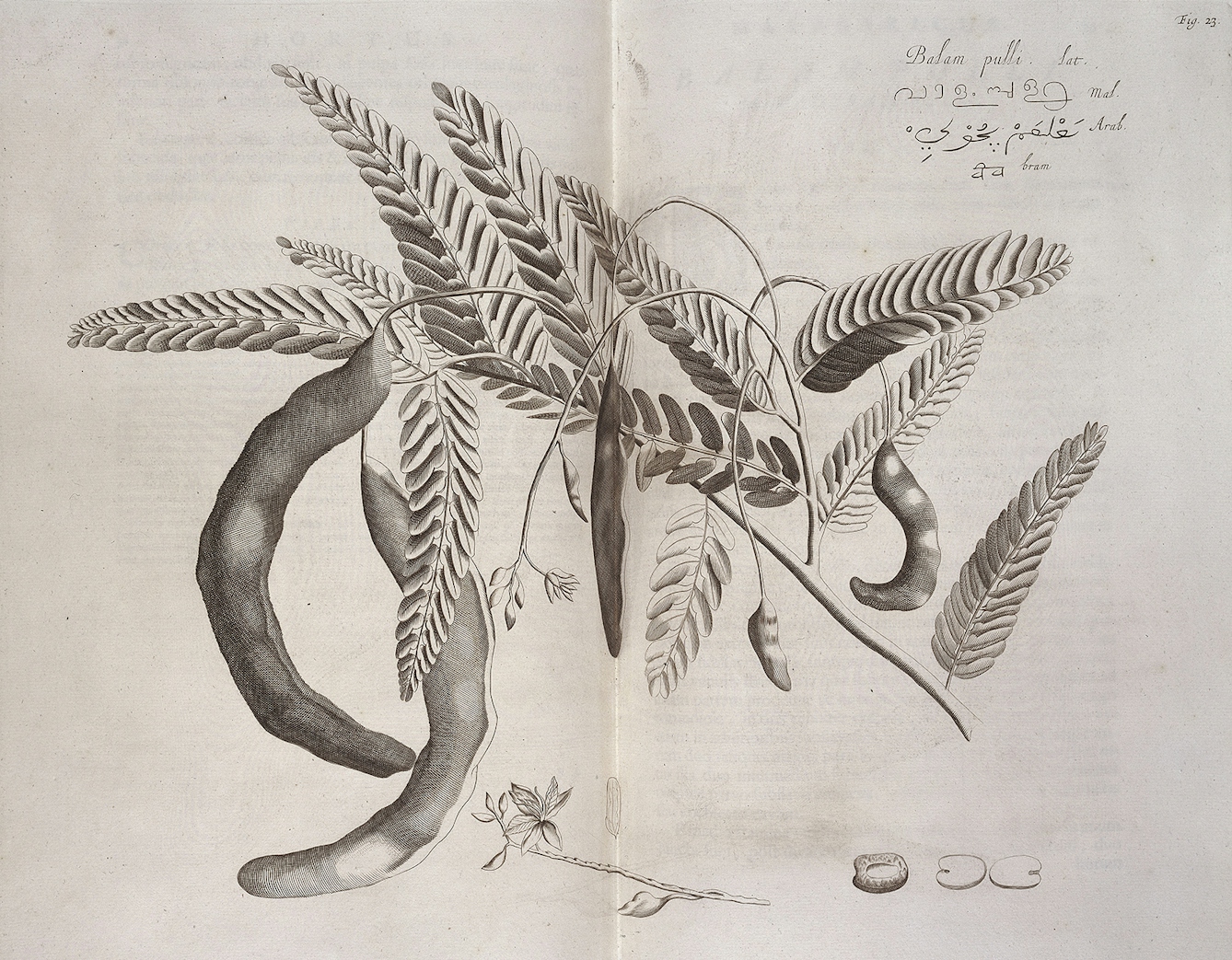

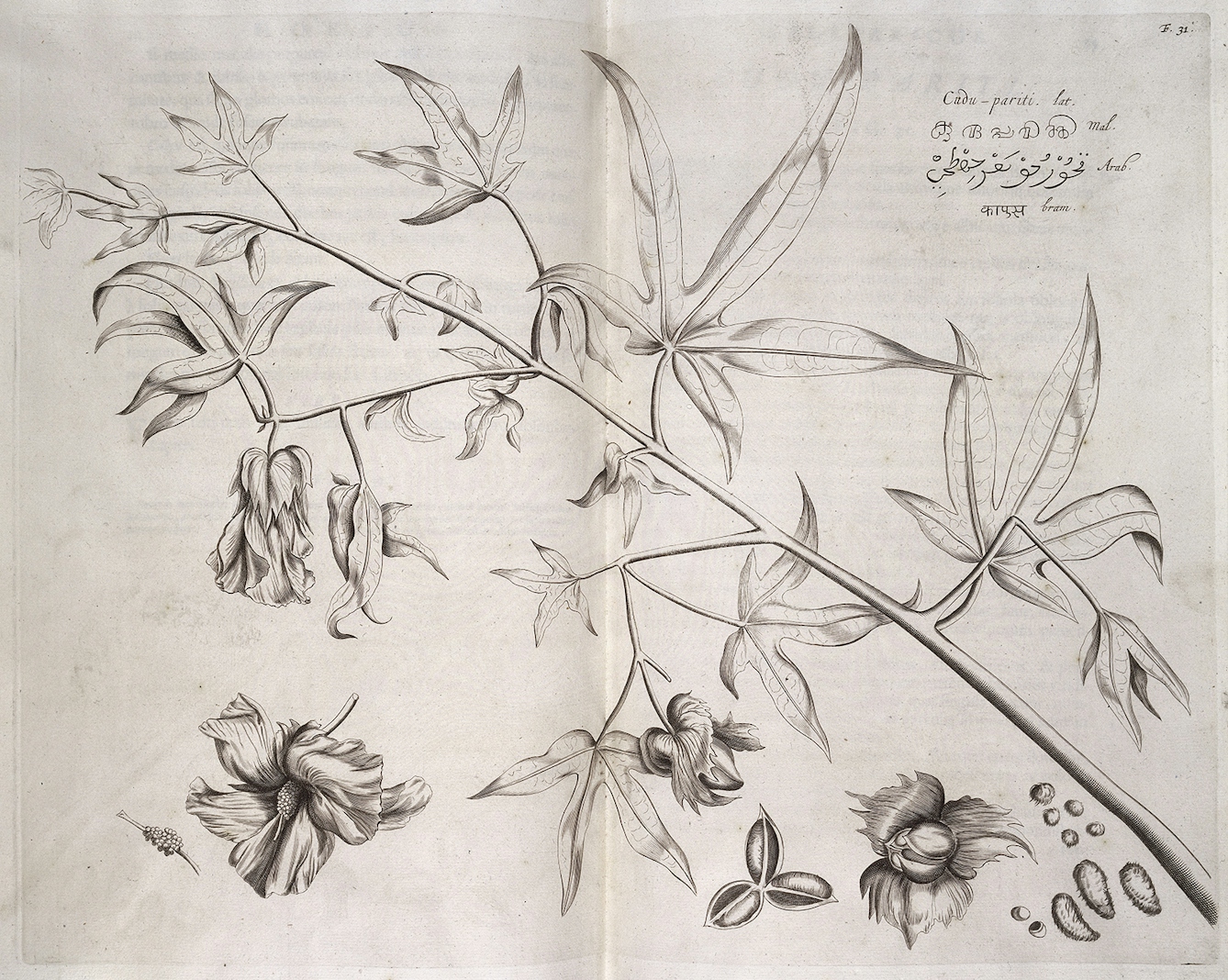

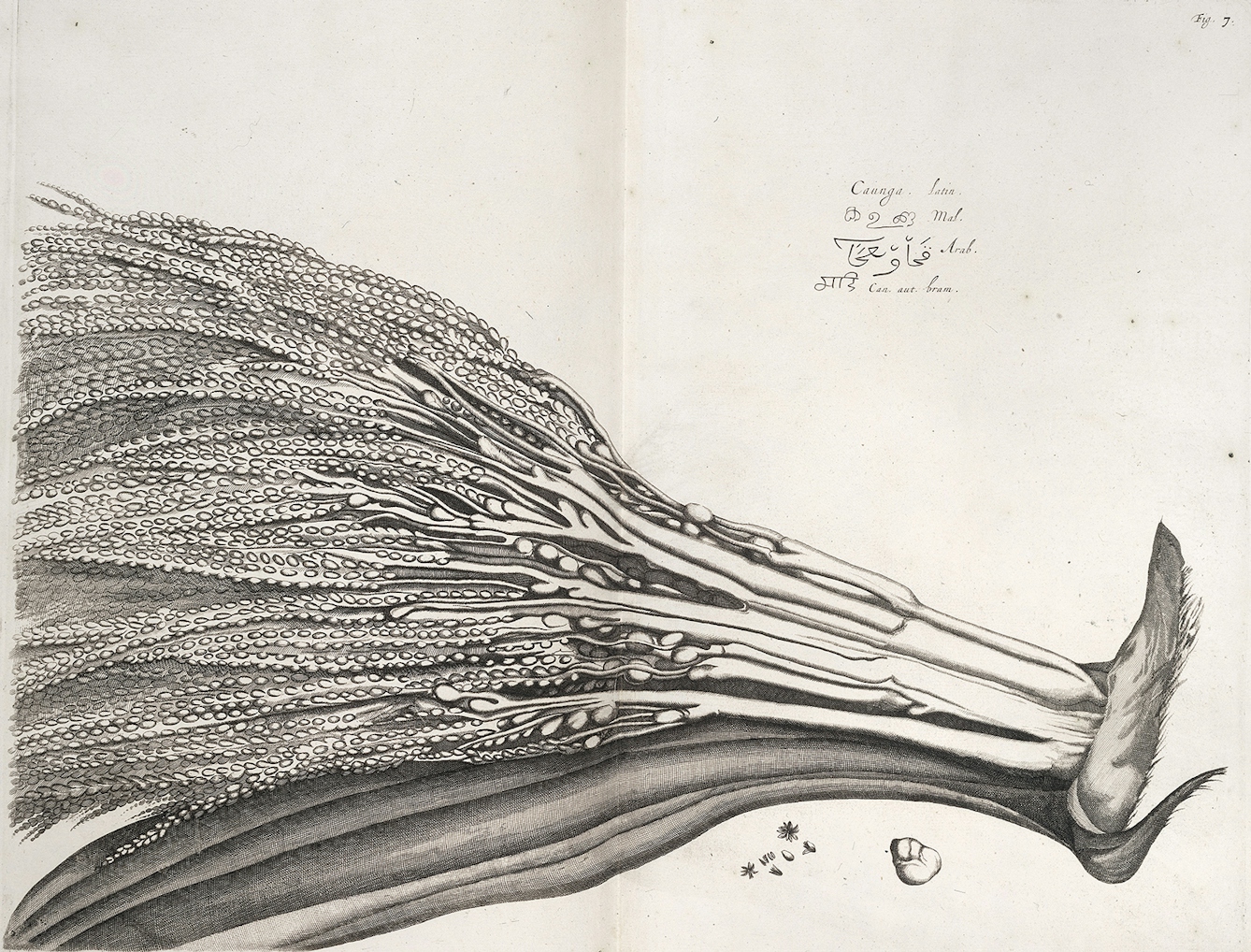

Illustrated pages from the Hortus Indicus Malabaricus, a book you'll find in our library. It's a study of the medicinal plants of the Malabar (a region beginning in south Goa and encompassing Kerala) made between 1678 and 1703.

Hortus Indicus Malabaricus

Hortus Indicus Malabaricus

I first came across de Orta through an exhibition hosted by the National Centre for Biological Sciences in Bangalore, which examined botanical interaction between the East and West during the pre-colonial period. Among botanical illustrations, prints and maps was the Hortus Indicus Malabaricus, a study of the medicinal plants of the Malabar (a region beginning in south Goa and encompassing Kerala) between 1678 and 1703. Commissioned by Hendrik van Rheede, an aristocrat who had been governor of Dutch Malabar, it was an ordered catalogue of nearly 800 paintings. Van Rheede had left home aged 14 to join the Dutch East India Company and had developed there a strong and mutually respectful relationship with Indian scholars and physicians, three of whom became contributors to his text. He also worked with Itty Achudem, traditional physician from the lower-castes who was an expert on local plants used in medicinal and culinary formulations, and whose medical palm leaf manuscript is thought to have been handed down through his family to the present day.

Curious to learn more about the pre-British colonial history of Indian medicines, I spoke to the curator of the exhibition, Dr Annamma Spudich, a scientist formerly of Stanford University who was born and raised in Kerala. I was fascinated by how – and why – a geneticist who had built her career firmly within the American university system had switched to the study of Indian scientific traditions. We chatted about the long trips she takes several times a year to Europe, Bangalore and Kerala, where she has been recording the work of India’s few remaining Ashtavaidyas, practitioners of a specialist branch of India’s Ayurvedic medicine.

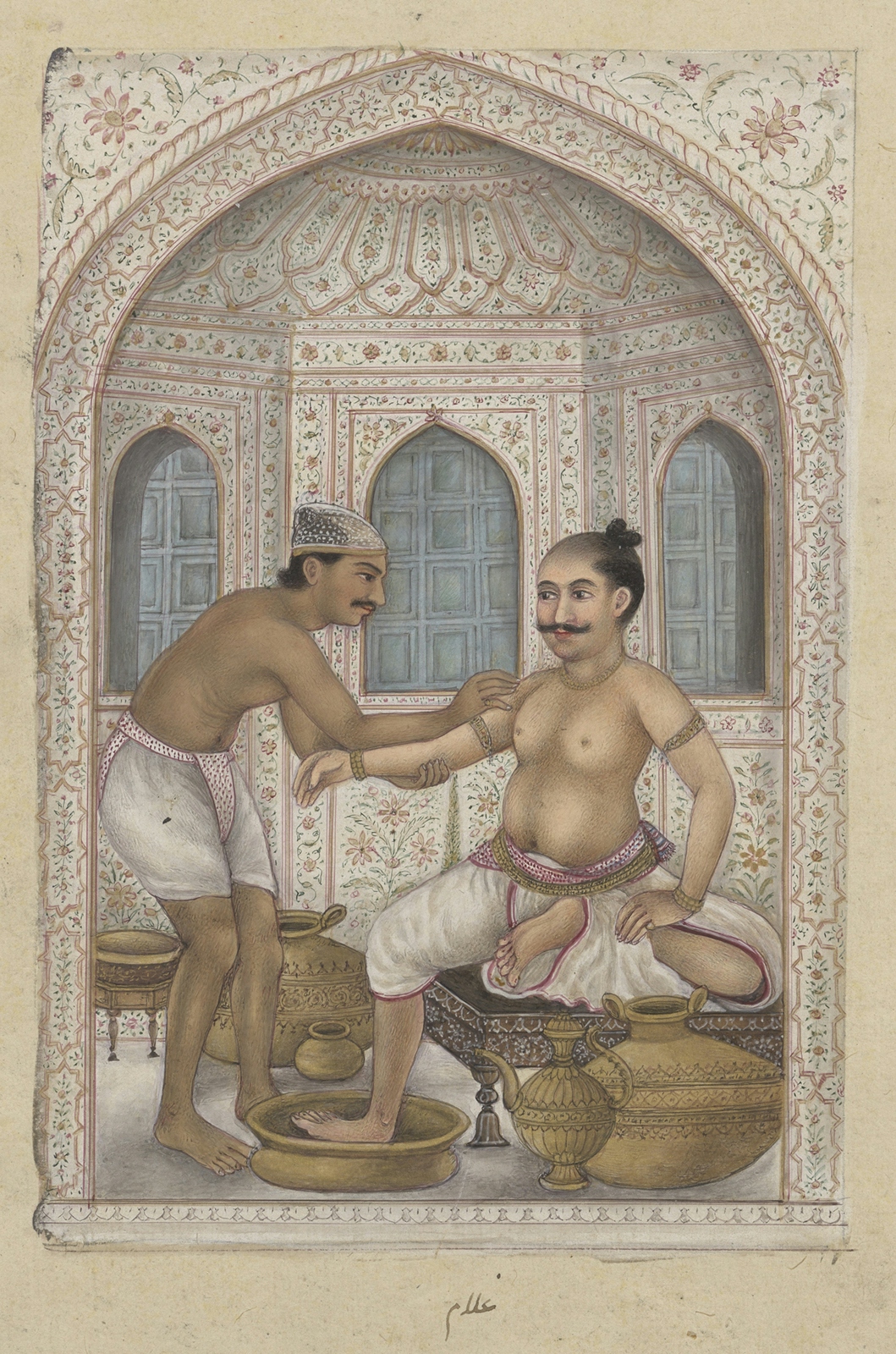

This painting from 1825 shows two Ayurvedic procedures. 'Snehana' involves massaging the body with oil to nourish the nervous system, while 'svedana' uses hot steam to flush out toxins.

The Ashtavaidya’s tradition had arisen from a historic interaction between text-based Ayurveda practices and regional folk medicine that drew on Kerala’s medicinal flora. Roughly translating from the Sanskrit as ‘the science of longevity’, Ayurveda is based on a theory of medicine originating in Brahmanic tradition and set down in Sanskrit texts in the early centuries of the Christian era. Its medical theory is based on humoral, physiological and pathological principles of a body in health and disease. Ayurveda covers an enormous number of practices and philosophy, from physical exercise and meditation (yoga) to diet, but at its heart it revolves around the three concepts of dosha, dhātu and mala. Dhātu are the body’s tissues and mala are its waste products. Dosha is a little more tricky to capture, but it is often equated with Hippocrates’ humours – though in Ayurveda there are three, not four. The doshas are semifluid substances in the body which regulate its state of balance. Of them, pitta and kapha seem to align with bile and phlegm, while the third, known as vāta, represents wind. The doshas interact with the body’s waste products and what are referred to as its seven constituents, namely blood, chyle (a milky fluid of lymph and emulsified fats), flesh, fat, bone, marrow and semen. Balance through moderation in all things is the way of Ayurveda – followers of the system are recommended only ever to take reasonable quantities of food, medicines, sleep, sex and exercise, so that the central process of the body, digestion, can do its work, allowing ojas, energy, to be extracted.

In general, the medicines used in Ayurveda have plant and animal origins. In some formulations, minerals and metals, including sulphur, arsenic, lead, copper and gold, have a central role, an innovation that was introduced around ce 1000. Around the same time, opium (historically prescribed for diarrhoea) began to be adopted, it is thought from Islamic sources. As this suggests, India’s most ancient living medicine has continually experimented, evolved and absorbed elements from other systems of treatment. Neither has it been uncritical of itself – Ayurveda today has been shaped by revisions and criticisms from within as well as from outside sources. As early as 1698 a vaidya (Ayurvedic doctor) by the name of Vīreśvara published a text debating illness and health in which he questioned the whole theory of humoral balance of doshas, adding for good measure, “it resembles the babbling of lunatics”.

This colour engraving from 1683 of a mango shows the fruiting tree, leaves, fruit, flower, seed and a cross-section of the seed.

I asked Anna about the idea that the study and veneration of plants were part of the culture of India. “Absolutely,” she said. “I grew up in Kerala. On my mother’s side we had many friends who were traditional physicians, vaidyas. We would call the vaidya as often as we went to the medical doctor. The vaidyas might prescribe a thailum, an oil, or maybe the extracts of two or three plants. We’d go to them for a large number of ailments. Of course, if you had appendicitis you’d go to the medical doctor, but from the vaidya we learned about plants that could help us. But this is how we learnt about plants – for an upset stomach, say, my grandmother would tell us to go to the garden and pick these leaves.”

I knew that, for minor ailments, my mother’s family in Tamil Nadu also called this pattivaidyam (granny doctor) or veetuvaidyam (home doctor). In their part of India this involved a mix of a system known as Siddha medicine. This is a system similar to Ayurveda in theory of causes of disease but different in origin; in the types of medicines used and in the ways they are processed; and with its own texts written mainly in Tamil, not Sanskrit. As well as Siddha, there were folk medicines handed down the generations and prescribed by mothers, grannies and relatives within the home – often simply from the spice cupboard in the kitchen. Like the Ashtavaidyas’ practice of Ayurveda, these home remedies were the result of an interaction between Indian medical theory and folk knowledge.

“That’s also part of the folklore of medicine”, Anna said. “Indian food is medicine. There is that overlap between them, inbuilt into the cuisine. There have always been these medical traditions, botanical-medical knowledge, massage therapy and so on. I was delivered by a local midwife, and for all of the problems that arose these women knew what medicine to administer. All this was part of our traditional systems – a new mother was bathed for thirty days with extract of certain leaves and roots, some of which helped with the contraction of the uterus – these women had a list of procedures and medicines of their own.

“It wasn’t until I was a teenager that a medical college was opened in Kerala. Now there are many medical schools and biomedicine is the dominant system. People want immediate relief with a single-molecule drug rather than wait for the lower concentrations found in traditional medicines to work.” Anna’s point was a significant one. Despite the fact that, according to the World Health Organisation, 70 per cent of people in India still use traditional medical therapy as a first line of defence, the way of thinking about medicine and the time frame in which results are expected have changed significantly. We want quick fixes rather than the protracted lifestyle changes that Ayurveda prescribes.

“You should come to Kerala with me and see how the physicians practice. There is a young Ashtavaidya who is trying very hard to preserve the traditions. He’s studying at an Ayurveda college. There is not much of the real tradition left.” Anna knew better than most how threatened the history of Ayurveda had become. She’d been devastated to discover that the palm-leaf manuscript that Achudem spoke of in the Malabaricus had recently been thrown away by his family. “It seems to have been suspended in the main house in a hanging basket and they weren’t sure what it was, so they put it in the rubbish. It was very sad,” she said, clearly frustrated. Perhaps even more sad is the fact that the loss of Achudem’s treasure is by no means an isolated case.

In pictures

Illustrated pages from the Hortus Indicus Malabaricus. It was commissioned by Hendrik van Rheede, an aristocrat who had been governor of Dutch Malabar, and contained an ordered catalogue of nearly 800 paintings.

Hortus Indicus Malabaricus

Hortus Indicus Malabaricus

Hortus Indicus Malabaricus

Hortus Indicus Malabaricus

Hortus Indicus Malabaricus

What Anna was saying reminded me of something van Rheede had written in the Hortus Malabaricus: that, even in 1678, the use of Indian plants “whose curative virtues were proclaimed by indigenous physicians as having been famous for extreme antiquity was rapidly approaching its end”.

A further reason for the demise of the Ashtavaidya’s work – which would have been a problem even when van Rheede was searching for collaborators in 17th-century India – had also emerged from Anna’s research. The traditional education of the old Indian medical scholar practitioners was exclusive, sometimes dependent on royal patronage and extremely long and demanding. Generally, such instruction was given only to men who were members of an existing practitioner’s family or of a high caste. A wealthy sponsor would also be vital in order to support what could be 15 years of rigorous one-to-one apprenticeship. Students would receive training in not only healing practices (study of the medical texts, diagnosis and preparation or medicine formulations) but also logic, astrology and additional periods of meditation and memorisation and recitation of classical texts.

This unwieldy system persisted until the 19th century, when a European-style fixed curriculum was introduced, with specialist subject teachers, a set training period and qualifying exams. Successful candidates would receive a medical certificate and a licence permitting practice. Ayurvedic and other traditional medical colleges in India still operate with a standardised syllabus that includes Western disciplines – anatomy, physiology, biochemistry – ostensibly so that the old and new can interact with ease. Although this streamlined system has turned out large numbers of traditional medical physicians and widened the availability of their services, the inclusion of Western practices is considered by many to have undermined the philosophy behind Ayurvedic medicine.

Still, things have been worse. In 1822 the British Raj outlawed the integrative approach pioneered by de Orta and colonial India’s various fledgling medical institutions would teach only the separate disciplines, rather than pushing for the pluralism which had been so effective.

Unsurprisingly, under the British, European medicine was to supplant all others. The English politician Thomas Babington Macaulay was the architect of this change. An uncompromising modernist and the son of a missionary, he considered the ‘pagan’ Indian systems of medicine to be both backward and slowing the progress of Anglicisation. Despite the protests of British Orientalists, he decreed that Ayurveda as a system of medicine was to end. At the new Calcutta Medical College, only one system was to be taught as medicine.

‘In the Bonesetter’s Waiting Room’ is out now.

About the author

Aarathi Prasad

Aarathi Prasad is a biologist and writer. She has appeared on TV and radio programmes, including BBC Radio 4, Channel 4 and the Discovery Channel. She is the author of ‘Like A Virgin: How Science is Redesigning the Rules of Sex’. She lives in London.