As she gets closer to Audrey Amiss through working on her archive, Elena examines the different perspectives that help build a picture of Audrey. Key among those are the recollections of her niece and nephew, Kate and Steve.

Audrey and her family

Words by Elena Carteraverage reading time 10 minutes

- Serial

Everything I know about Audrey Amiss, I know from cataloguing her archive, from seeing her sketchbooks, and reading her diaries and notebooks. But when you’re discovering a person through the objects and papers they’ve left behind, is it possible to understand who they were in a meaningful way?

Those records hold a ghost, just one side of the story of Audrey as a person. I wanted to find a way to connect to who she was and to understand her relationships with others who knew her.

During the cataloguing of the collection, my colleague Anthony and I stayed in touch with Audrey’s niece and nephew, Kate and Steve. It was Kate and Steve who donated the collection to Wellcome after discovering it in Audrey’s flat after her death. Audrey’s parents are no longer around, and her sister Dorothy passed away in 2022. Speaking to Audrey’s niece and nephew felt like some way to get closer to understanding Audrey.

“She comes into my mind whenever I’m in London,” Steve says to me on a visit to Wellcome Collection. Audrey was born in Sunderland, where she spent her early life before moving to London to study art at the Royal Academy. Not long after, Audrey had her first breakdown, her mum Belle sold up the corner shop in Sunderland and the two of them lived together in London until Belle died in 1989.

I watch Steve look through a scrapbook we’ve pulled off the shelf in the basement stacks. He turns a sticky page and reads an annotation below a packet of pickled herrings: “Suggests Seaburn, Sunderland North.” Then on the next page: “The grey wood green suggests the sea. Sunderland North, Scottish connection.”

“She’s never far away from where she grew up, is she?” he says.

PP/AMI/A/3. Family photographs of Audrey. Left: Audrey (left) with her sister Dorothy. Right: Audrey (left) with her sister Dorothy (centre) and her mother Belle (right).

And London is always present in her works too – you could draw maps of the routes Audrey took every day between local supermarkets, corner shops and department stores, through parks and on Tube journeys, making similar journeys day after day around London. “Sketching in Brixton today was a burst of sunshine in a despairing world,” she writes to Dorothy.

Ways of seeing

Steve remembers the birthday and Christmas cards he received from Audrey. She sent them every year, even when he wasn’t in much contact with her, he tells me. The cards were always homemade; she’d stick stuff down that she’d found: junk mail, packaging – things that caught her eye. “She doesn’t see a biscuit wrapper the way I see a biscuit wrapper,” he remembers. “She sees whether it’s a beautiful object or not.”

A few days after Audrey died, Steve received a final birthday card from Audrey. Steve wonders aloud whether he still has that card somewhere, or whether it would have been chucked out at some point. Even though Steve recalls his aunt, there’s still something about this final card as a physical thing, as a memento of Audrey.

There’s something poignant and tangible about the card, about it arriving after Audrey’s death, about Audrey never forgetting a birthday or a Christmas, of staying in touch while also being often very far away in her own thoughts and experiences.

I ask Steve what he remembers about Audrey. He talks animatedly about the way she saw the world, and how she was always interested in everything. He remembers how these moods might change when she was heavily medicated, with Audrey visiting at Christmas and just sitting on the sofa and staring at her hands quietly.

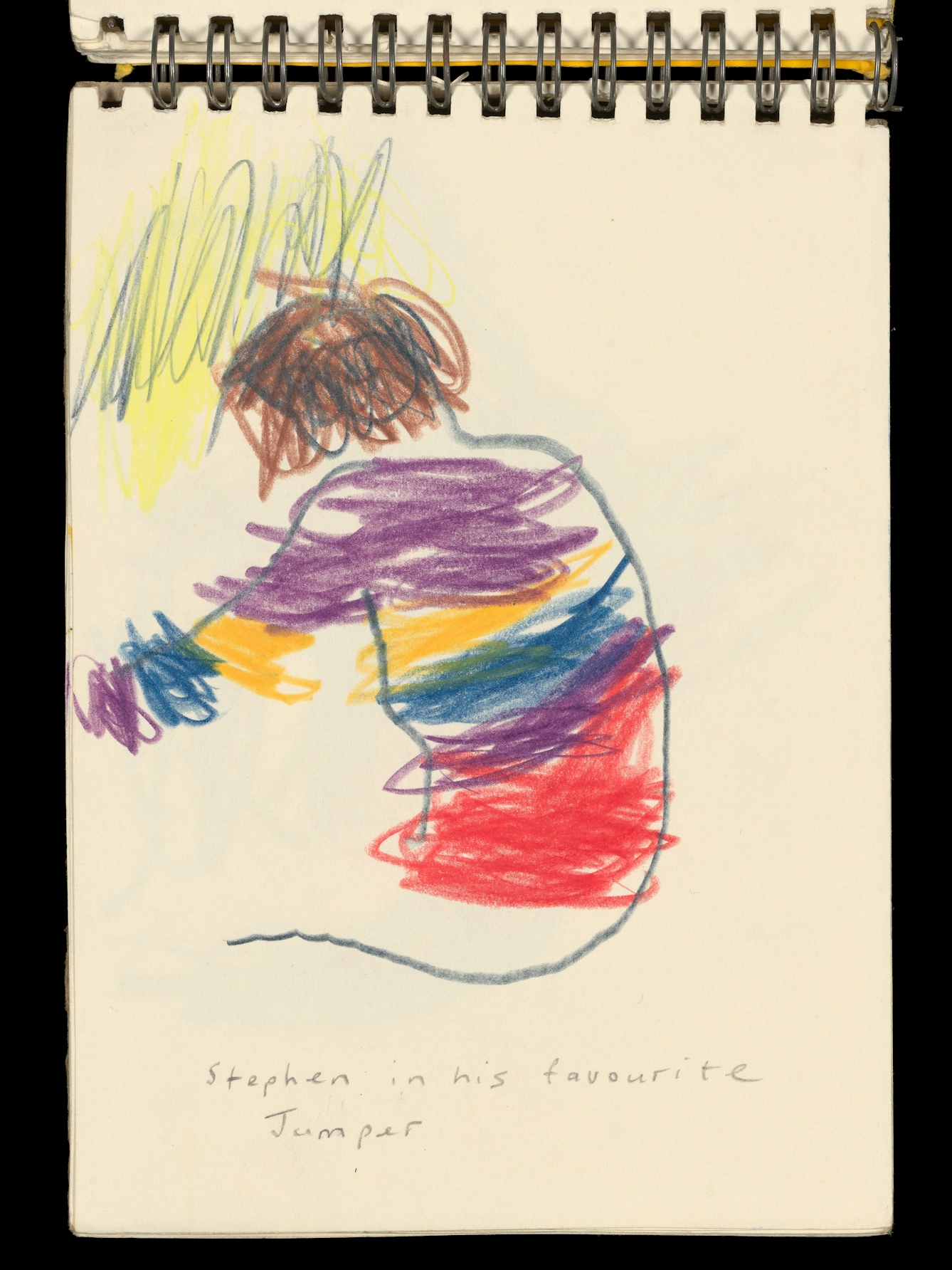

PP/AMI/B/65b: Sketchbook. Sketch by Audrey of her nephew Stephen in his favourite jumper.

He remembers that she hated being medicated and felt it dampened her spirits. She had an almost violent intensity when you got her on to a subject she was interested in.

Audrey’s niece Kate remembers stopping at some traffic lights in the early 2000s and watching an elderly and seemingly homeless lady shuffle across the road in front of her. She was wearing slippers and eccentric clothing, carrying stuffed plastic bags. It took her a moment to realise that woman was Audrey. The family had long periods where they didn’t see Audrey at all, where she was withdrawn or volatile and they kept their distance.

Sister care

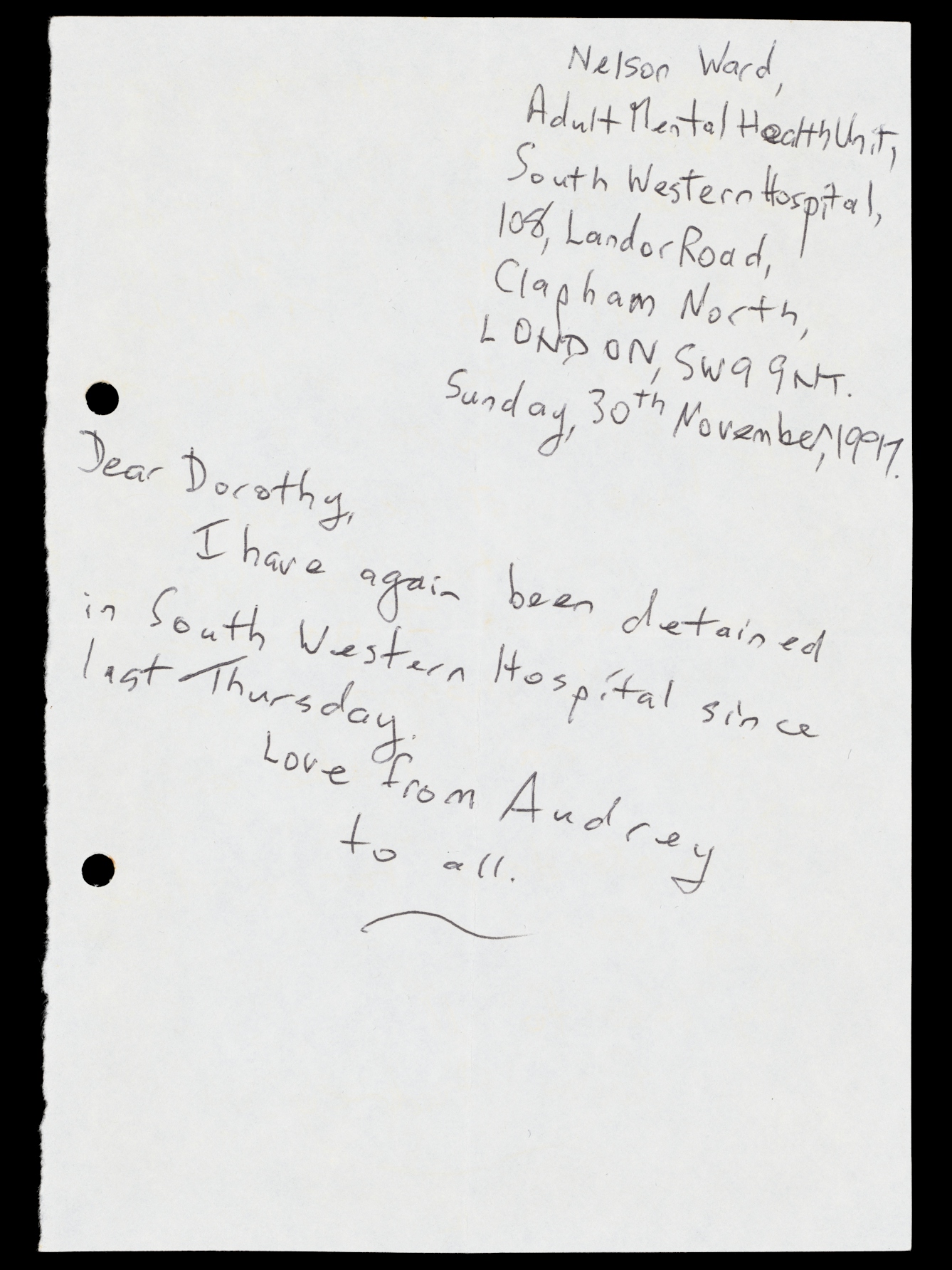

The relationship wasn’t an easy one, but Audrey’s sister and mother always tried their best to care for Audrey, Kate remembers. Two heavy box files in the archive are labelled “soeurcare” (sister care) and contain neatly filed letters Audrey wrote every week to Dorothy. These are letters Dorothy donated to join Audrey’s archive; Audrey seems to have rarely kept the responses Dorothy sent back.

There are also letters from hospitals and the police informing Dorothy when Audrey had been incarcerated. This act of “sister care” is one of careful monitoring and tenderness, dutifully noticing changes in Audrey’s handwriting and moods, and an often fraught and laboured attempt to care from afar.

She’d take a plastic carrier bag with her everywhere so that she had pens and a sketchbook just ready for whenever she wanted to draw something that she saw.

PP/AMI/H/1/3b: Letter from Audrey Amiss to Dorothy informing of her detention at South Western Hospital, Nov 1997.

But there was laughter too. Hysterical peals of laughter watching Monty Python or when something tickled her just right, as Kate remembers. That comes through in the archive too, I think – cataloguing the collection, there are moments when I could almost hear Audrey’s laughter through the page.

I think about Audrey writing about being thrown out of court for laughing in the public gallery, about her joy at seeing animals at the zoo. Reflecting on her visit to Hong Kong, Audrey wrote in a diary: “the situation was so ludicrous, I burst out laughing and the laugh rang out all over the airport. I laughed so much I wet myself.”

In that account she describes herself as a “big blowsy woman wearing a Chairman Mao cap with badges tilted at a rakish angle”, and I’m struck by the thought of how that trip ended – with Audrey arrested, deported, and taken to a hospital back in London.

Audrey’s view of the world

She’d really examine things, Kate remembers. She’d unwrap a Christmas present so delicately and remove every piece of Sellotape and crane her neck round to peer inside and exclaim loudly and be really pleased at whatever was inside. “It’s a nice memory,” Kate says. “I can even see her with a cup of tea, holding it and really examining the mug up close, and I don’t know what she was seeing, but it was probably not what I was seeing.”

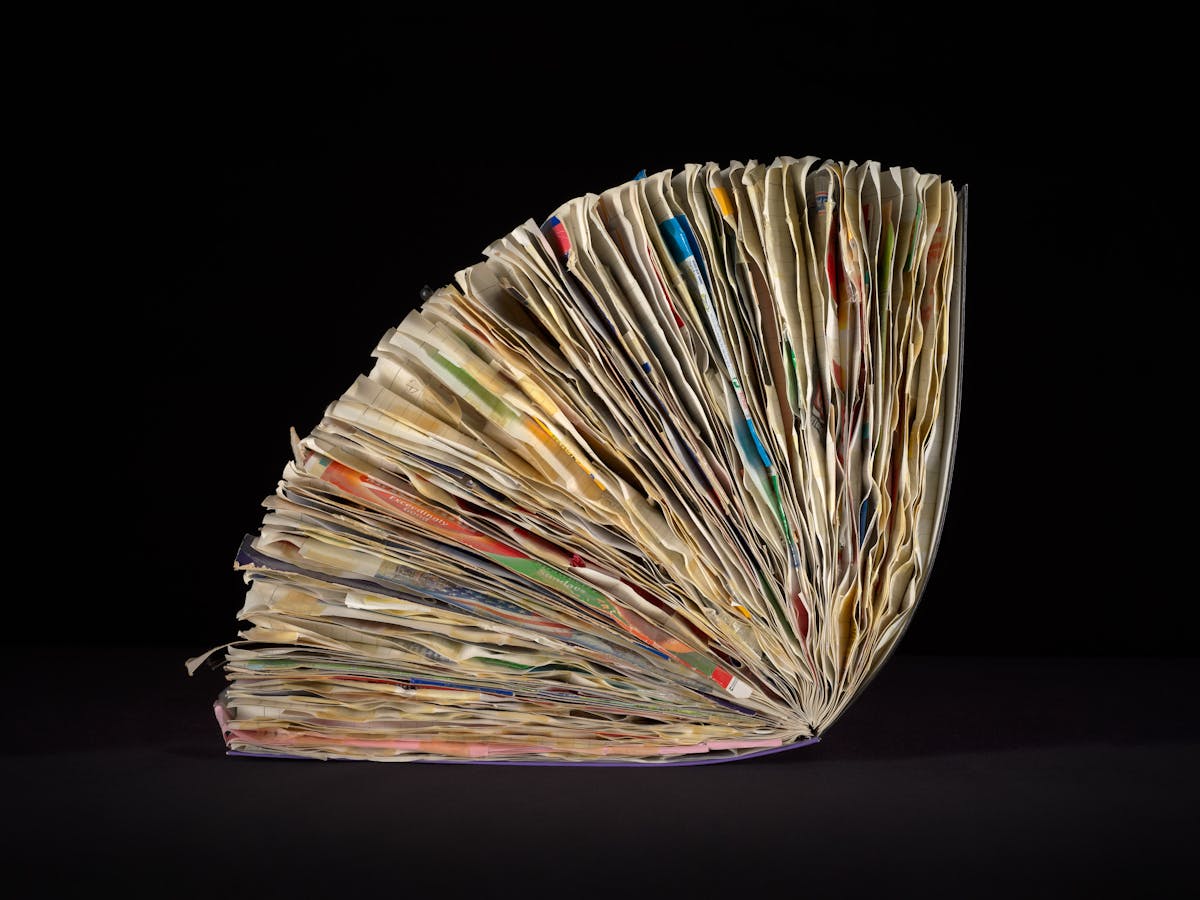

I think about how that comes across in the archive too – when a disposable coffee cup is pasted down in a scrapbook, Audrey writes about the perforations and the waves in the corrugated card, about the tiny crosses on the base of the design. In that way, the archive gives a glimpse into Audrey’s inner thoughts and how she saw things: the coffee cup is annotated with associations, thoughts, a drifting stream of consciousness evoked by the details on the cup.

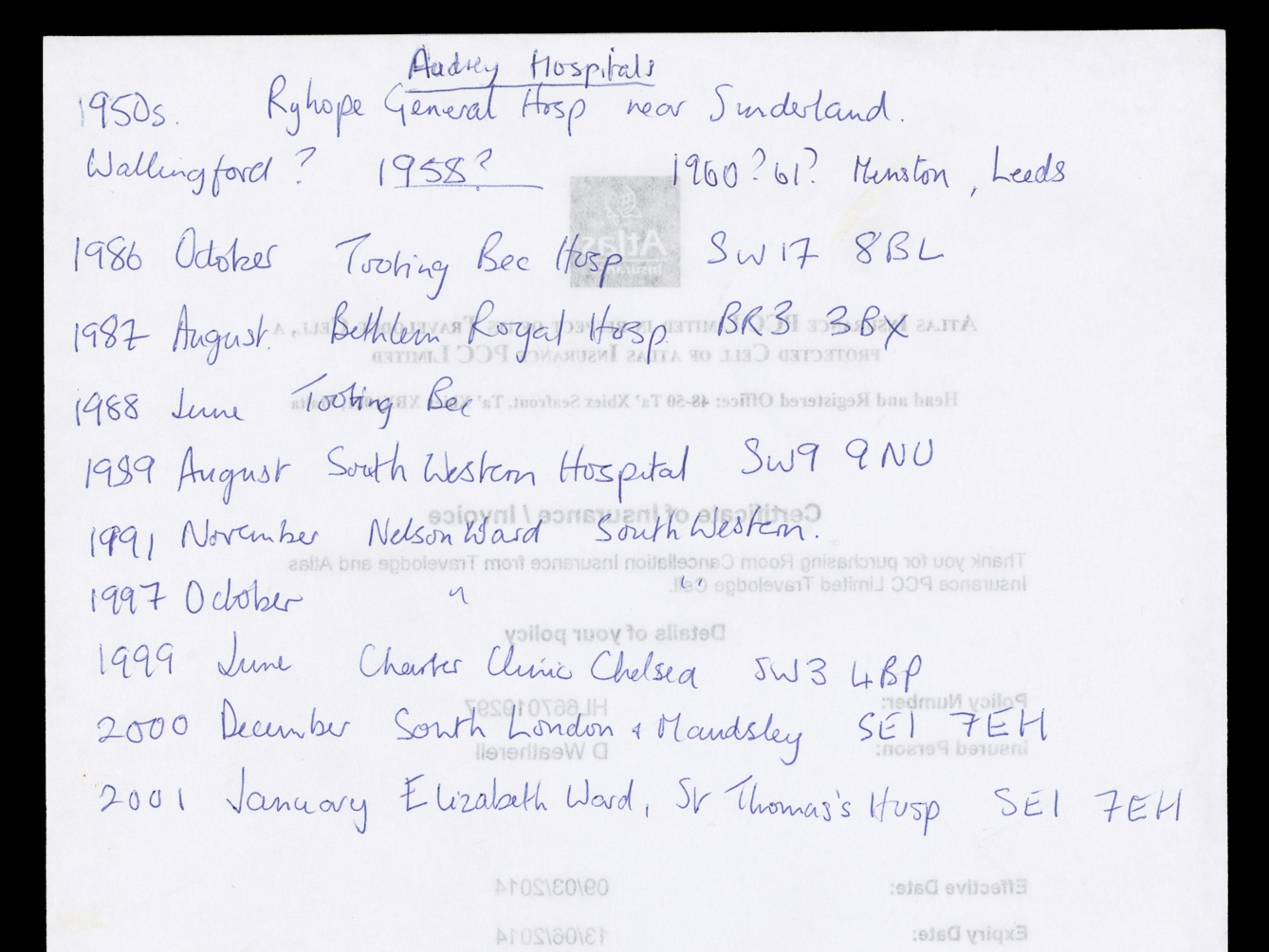

PP/AMI/H/3: Collected letters. ‘Audrey’s Hospitals’: list written by Dorothy Weatherell (née Amiss). 2014.

“She just saw things in a different way,” Kate says. She had an utter compulsion to paint and draw and re-create things, and she’d take a plastic carrier bag with her everywhere so that she had pens and a sketchbook just ready for whenever she wanted to draw something that she saw. She would have loved the pleasing feel of putting together the scrapbooks, of seeing the way the packaging sat on the page and getting the composition just right.

When Kate and Steve visited the flat after Audrey’s death, a sketchbook was on the table next to a fruit bowl, some of her final sketches in the notebook. On the floor was the carrier bag she’d taken everywhere with her, with a felt-tip and a pen in it that she’d used to draw the bowl of fruit.

There were sketchbooks and scrapbooks everywhere in the flat, on every surface, and in every drawer, Kate remembers. It was entirely overwhelming. And then in the middle of all of this, there were framed photographs of Steve and Kate, and a pen pot Kate had made as a child as a Christmas present for Audrey. Kate was struck by how it felt like a time capsule, and there’s a poignancy in imagining Audrey alone in the flat, but with old family mementos around her.

“My daughters say they wish they’d known Audrey,” Kate says, and I realise that’s something that Anthony and I have often thought too. There’s this sense of wanting to somehow get closer to understanding, or to knowing what Audrey would have thought of all of this.

PP/AMI/B/271: Sketchbooks. Studies by Audrey of her “Mam reading the paper”. 1987.

Invoking the ghost of Audrey

Speaking to Audrey’s family gives me a sense of who Audrey was to them and in their lives. It reminds me that Audrey’s illness had its own weight on the family, and caused tension and distance at times. Looking through the archive, it felt that both Kate and Steve had moments of recognition of the auntie they knew, but also moments of seeing Audrey anew, through her own words.

After someone dies, there’s an almost inevitable process of mythologising or storytelling as we try and make sense of their life. In cataloguing Audrey’s collection, Anthony and I had to make decisions about how we organised and described material, and in doing so we were also aware of filling in gaps and creating stories about who Audrey was.

We never knew Audrey in person, and speaking to her family feels like the closest way to understand who she was in relation to them. But who we are to our family is not a full reflection of who we are as a person, and it just adds one extra layer to understanding Audrey. Just like the archive holds a ghost of Audrey, so too do her family’s memories of her.

There will be other people who encounter Audrey’s collection and feel some connection to it and perhaps wish they’d known her when she’d been alive. As Audrey becomes more well known, it’s possible that people who did know her will emerge and reconnect with her works. And as the archive takes on a life of its own, different ways of seeing Audrey and the collection will come to light.

The archive provides an unfiltered plunge into Audrey’s world, through her own words, unmediated thoughts, and drawings. This is a different way of understanding Audrey from the way those who knew her personally in her lifetime did, but a way of connecting to Audrey that is no less valid.

At the end of a life, all we have is stuff. When that stuff is preserved, saved, archived, it is opened to the world to interpret and piece together in infinite different ways.

You can explore the Audrey Amiss archive through our online catalogue. To see the archive, you need to join our library and request to view specific items from the collection.

About the author

Elena Carter

Elena Carter focuses on developing the collections at Wellcome to challenge the way that we think and feel about health. Elena is particularly interested in radical and social histories and material that gives voice to marginalised groups. As Collections Development Archivist, she works directly with people to find the best home for their materials, with a focus on working collaboratively and ethically.