While the right opportunity can spur people to commit some types of crime, such as burglary, homicide is linked more with emotions than opportunities. Laura Bui delves into our love of true crime stories and the research that explores whether a person can ever be a born criminal.

Are people born violent?

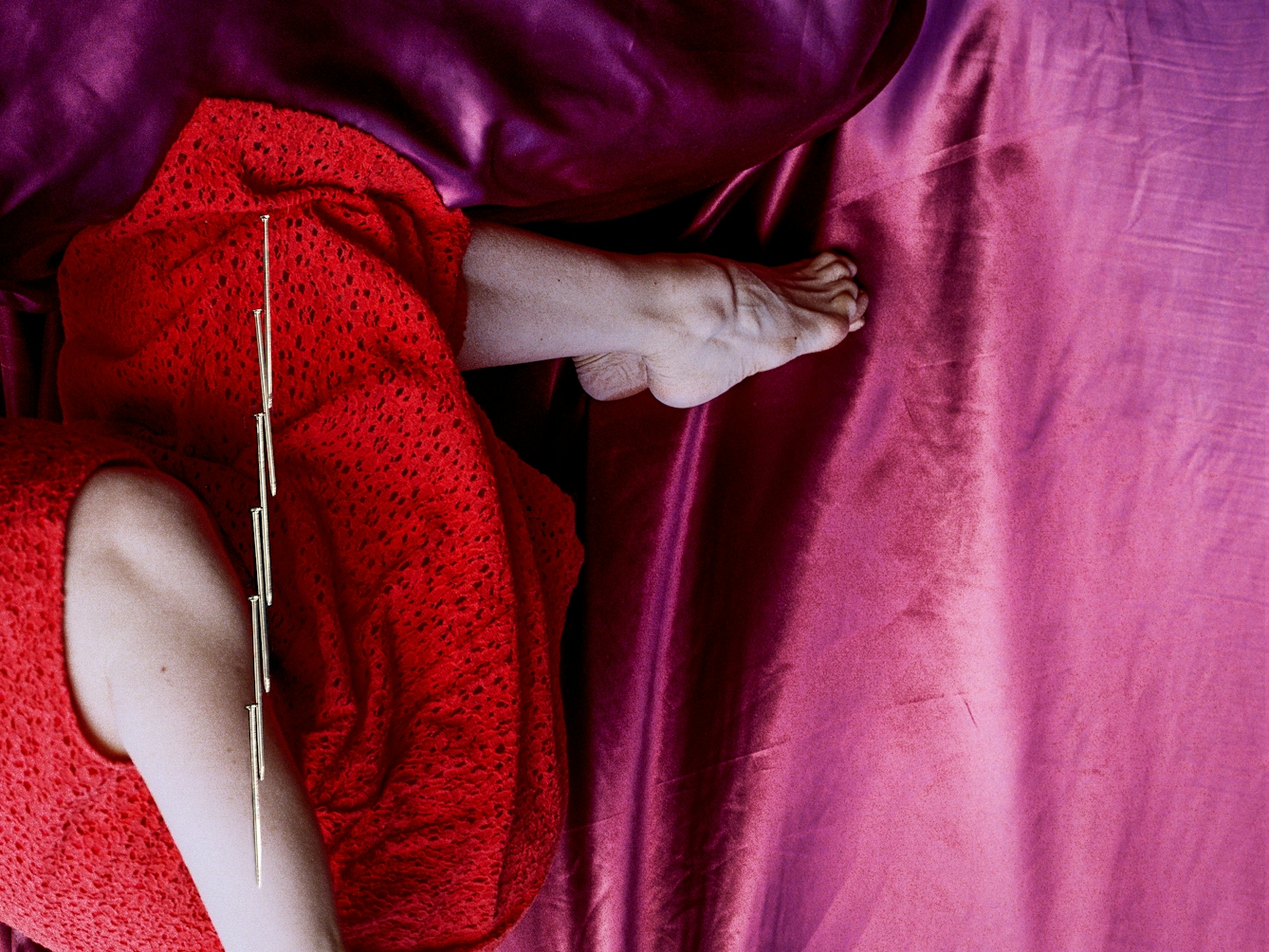

Words by Laura Buiartwork by Jessa Fairbrotheraverage reading time 7 minutes

- Serial

Across the globe, lockdown measures were related to a large reduction (minus 37 per cent) in urban crime, suggesting that opportunity to commit and get away with offences mattered more than the motivation of the would-be offender.

The crime that decreased the least, though, was homicide. One of the reasons is that a considerable number of homicides happen in domestic settings, and lockdowns did not change that situation. Compared with other crimes, homicide tends to be linked with emotions – think “crimes of passion”.

Homicide tends to pique more interest, even fascination and obsession, because, unlike crimes of opportunity – hey, a window was left open and no one was around – there is likely a good origin story (read: dysfunctional and full of adversity) behind the culprit, so we want to know: why?

Violence, with homicide considered the most serious interpersonal form, has major currency in today’s love for true crime. The quintessential question that consumers of true crime try to address with these morbid cases is whether the deed is intrinsic to that individual – whether they’re an inherently bad person.

Biology, brains and born criminals

The notion of the inherently bad person is better known as the “born criminal”, and it emerged in the late 19th century. Its major figure was an Italian doctor, Cesare Lombroso, who viewed criminals as relics of a primitive human phase because of their inferior mental and physical features.

Today, it is easy to laugh at Lombroso and his blatantly problematic work but it reflected the prejudices of that time. A founder of British criminology, Leon Radzinowicz, though, was quick to point out that: “Long after so many of us have been utterly forgotten or hardly remembered, Cesare Lombroso will continue to stand out as the originator and creator of the discipline of criminology.”

“Homicide tends to pique more interest because, unlike crimes of opportunity, there is likely a good origin story behind the culprit, so we want to know: why?”

Being a “born criminal” suggests a biological basis, and in recent decades, interest in understanding violence through biology has surged, attributed to increasing sophistication in brain-imaging technology, and advances in molecular and behavioural genetics that show that, to some extent, behaviour has a genetic basis. The implication of this work is that those who are violent are different from those of us who are not. If so, then violence can only be intrinsic to some – or is it?

I cannot talk about biology and violence without talking about Adrian Raine. Years ago, when I was a postgraduate student, I knew nothing about contemporary research on biology and violence until he arrived as visiting professor and gave seminars on the topic.

Tumours or head injuries seemed connected to transforming law-abiding citizens into violent law-breakers.

I was surprised to learn that a lot of research and evidence existed. Changes in the brain were related to changes in behaviour, as tumours or head injuries seemed connected to transforming law-abiding citizens into violent law-breakers.

The 1991 case of Herbert Weinstein was the first murder trial to use brain scans as a defence; Weinstein had argued with his wife, and uncharacteristically strangled her and threw her out of their 12th-floor apartment window. It was later discovered he had a large cyst in the front of his brain, and this was thought to have altered his behaviour by impairing his ability to control his impulses.

The seminars on biology and violence, especially related to the brain, revealed significant issues and controversies relevant to criminal responsibility and morality – why we think someone is responsible for their actions.

“Once upon a time, it was nature versus nurture, where some argued that the former contributed to committing crime and violence more so than the latter, and vice versa.”

The importance of social environment

Raine can tell you why the most violent people do what they do, and if they are ‘born’ that way. He even did so recently in a three-part series, ‘What Makes a Murderer’, with forensic psychiatrist Vicky Thakordas-Desai. Raine’s name became rooted in bio-neurological research on crime and violence when he was one of the first to scan the brains of murderers to compare them with those of people from similar demographics who were not murderers.

Where contemporary biological research on violence, including his, departs from or actually elaborates on and refines Lombroso’s work is in the inclusion of the social environment.

Once upon a time, it was nature versus nurture, where some argued that the former contributed to committing crime and violence more so than the latter, and vice versa. Now, this dichotomy is considered embarrassingly parochial, as advances in biological research on violence have established that it is an interaction between the two.

This is the crux of Raine’s social-push hypothesis. Although meant to explain antisocial behaviour generally, it can apply specifically to violence.

The theory tries to explain when adverse biological features, like complications during birth and poor executive functioning – which is related to problems in planning, problem-solving and concentration – matter in goading someone towards violence. When the social environment is favourable, like having parents who are supportive and set clear rules, or high socio-economic status, adverse biological features will be a likely reason for why someone commits violence – there are no harmful social factors to push someone into violence.

“Where contemporary biological research on violence departs from Lombroso’s work is in the inclusion of the social environment.”

The opposite is proposed for those in highly unfavourable social environments; it is those adverse social features that would better explain why someone commits violence rather than biological ones. When aspects of biology and social environment are both considered adverse, this substantially increases one’s likelihood for violence. What this research suggests is that, depending on who we are and what we are born into, we all are susceptible to violence.

Raine’s work lends itself well to our current love of crime drama and true crime. The producers of the hit series ‘Homeland’ had even created a show based on his book, ‘Anatomy of Violence’. One of the characters, a criminal psychologist who teams up with a young female FBI agent, was called ‘Adrian Raines’.

The media and the message

In that summer when life slowly returned to what it was just before the pandemic, I finally met Raine in person again and asked what motivates him to partake in crime as entertainment. There is a sense in academia that participating in such things – tracking the life histories of serial killers on TV, going on breakfast shows to give your thoughts on the latest sensational crime, writing books about the psychopaths and notorious murderers you’ve met – is not respectable.

Raine told me that he feels a responsibility to the perpetrators and victims, as his work has shown that many of these “born criminals” are not so – their violence contains echoes of what happened to them, circumstances they had little to no control over. Biology matters just as much as the social environment, and ways to effectively prevent violence will need to consider both of these aspects about ourselves.

If his work is attractive to media entertainment, then why not? Its messages can reach a much wider audience, and maybe reach someone who actually has the power to do something good about it. For example, a policy-maker or a prison governor in charge of selecting and implementing rehabilitation programmes.

One message is that violence is likely to occur because of an interaction between adverse elements in biology and the social environment – but what exactly were these circumstances that Adrian was referring to that were beyond someone’s control?

About the contributors

Laura Bui

Laura Bui teaches and researches crime and violence at the University of Manchester. Her research on these topics has appeared in academic journals and also in places like the literary anthology ‘Test Signal’, where she explored grief and the paranormal; the non-fiction journal ‘Tolka’, where she questioned what a (criminal) psychopath is really for; and BBC Radio 4, where she raised the questions we should really be asking about true crime.

Jessa Fairbrother

Jessa Fairbrother is a visual artist using photography, performance and stitch. Her long-term investigations revolve around subjects of yearning and the porous body. Her work is held in numerous private and public collections worldwide, including Tate Britain, the V&A, the Yale Center for British Art and the Museum of Fine Art, Houston. Her work is represented by the Photographers’ Gallery, London and AnzenbergerGallery, Vienna. She is also a QEST (Queen Elizabeth Scholarship Trust) scholar.