Growing up as a thalidomide survivor meant coping with all the usual challenges of childhood and adolescence, while having to fit into a world designed for the able-bodied. Most of them had to make compromises in order to balance the demands for ‘normality’ against their individual needs for independence and acceptance.

Adapting to life as a thalidomide survivor

Words by Ruth Blueartwork by Hollie Chastainaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

The true extent of the damage caused by thalidomide became clear in the 1960s, as the story began to break in the press. For the families of thalidomide-affected babies, the long battle for compensation and recognition had only just begun. Their priority shifted to thinking of ways to ensure a decent quality of life for their child, including getting the health and medical support they would need for the rest of their lives.

Alongside this, attempts were made by the medical profession to replace what was missing, in the form of prosthetic limbs.

Compensating for thalidomide impairment

Children with impaired limbs were treated in clinics with experience of dealing with amputees, such as Queen Mary’s Hospital in Roehampton. The hospital was renowned for rehabilitating soldiers over two world wars at its limb-fitting and amputee-rehabilitation centre.

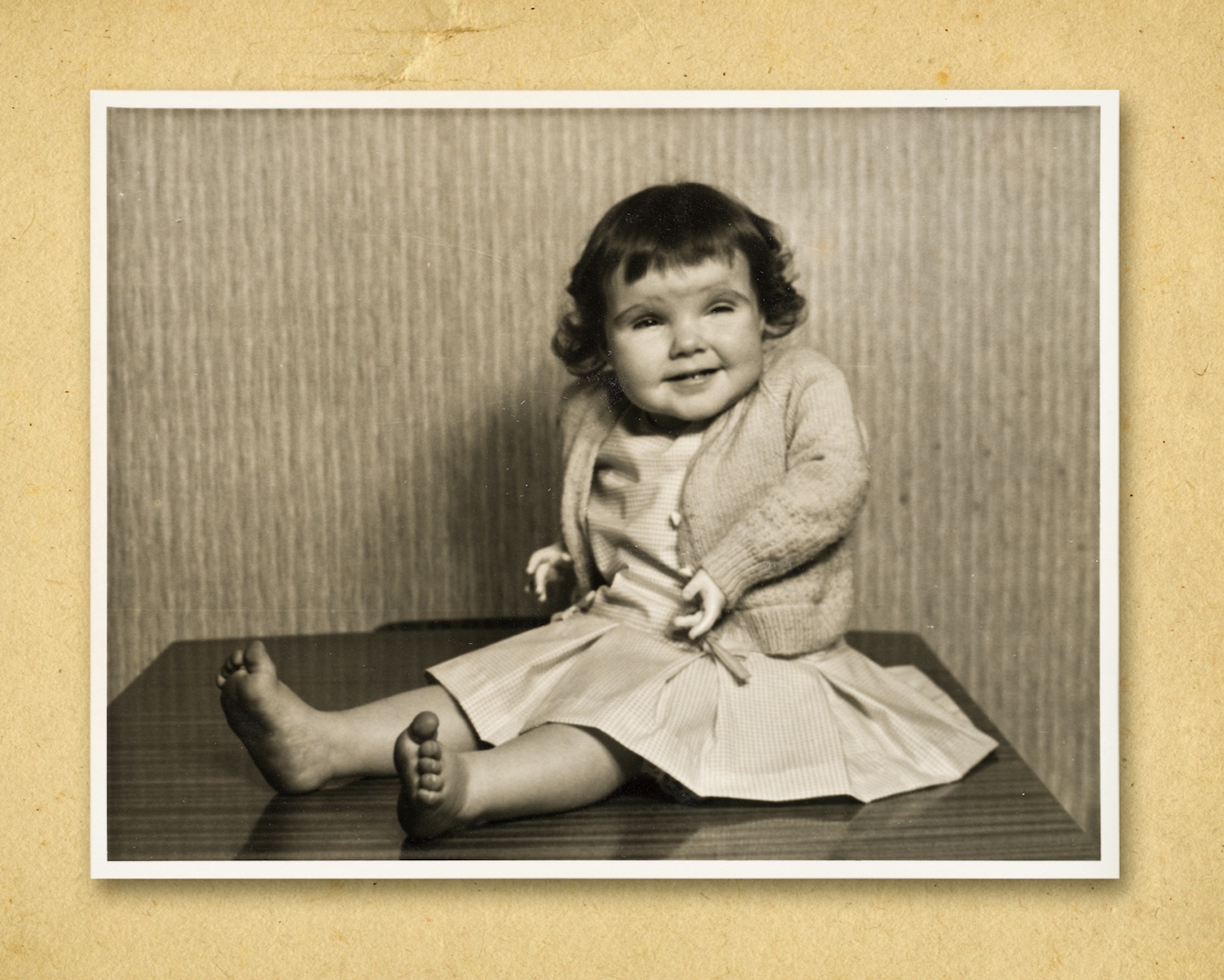

Thalidomide-impaired children started being fitted with prosthetics and supports from as young as three to six months of age. The purpose and function of prosthetics depended on whether they were for meant for upper or lower limbs.

Lower-limb prosthetics

Very young children with lower-limb impairments began their prosthetic journey with ‘sitting sockets’ to aid balance and help them sit upright. They then progressed to block feet on rods, which enabled them to stand. As the child grew, the limbs became more complex, sometimes including articulated knees to aid walking and sitting.

Tracey standing on block feet with articulated knees.

Little had changed in prosthetic design since World War II, when prostheses were designed to attach to the stump of the limb of an adult amputee. One of the difficulties for thalidomide survivors was that their existing limbs rarely fitted into such prosthetics neatly, the way an amputee’s stump did. Sometimes the more obtrusive parts of their limbs might need to be amputated in order to fit comfortably.

Wendy had her feet amputated when she was seven so that she could use prosthetic legs for walking. With the matter-of-fact curiosity of a seven-year-old, she remembers asking her father what would happen to her feet after they were removed.

Her school friend, Geoff, was “devastated” to learn that her feet had been removed, but for Wendy, who still uses prosthetic legs today, being able to walk unaided was liberating.

Wendy.

Kath’s experience was different. She learned to walk with prosthetic legs without any amputations and she found them difficult to manage: “It was heavy; it was hot; it was bulky.” She walked with prosthetic legs until the age of 13, and she attributes some of the back pain she endures as an adult to her struggles with the prosthetics.

Kath.

Upper-limb prosthetics

Upper-limb prostheses were aimed more at creating a sense of visual ‘normality’ and very rarely improved limb functionality. There were several types of upper-limb prosthetics: ‘dress’ arms, which had no function except to give the illusion of an arm inside clothing; slightly functional arms with basic split hook hands; and gas-powered prostheses, which offered more functionality but were cumbersome and difficult to wear.

All of these options had the disadvantage of denying the child access to the sensations and feelings available through the skin and sense of touch of their existing impaired limbs.

Mandy was given prosthetic ‘dolly’ arms from the age of six months so that she “wouldn’t be unacceptable to look at” when her mum took her out in the pram. For Mandy, “looking normal” often had more to do with making other people feel comfortable with her disability than making it easier for her to be accepted.

“Mandy was given prosthetic ‘dolly’ arms from the age of six months so that she ‘wouldn’t be unacceptable to look at’ when her mum took her out in the pram.”

By the time she started school, she had progressed to more functional gas-powered arms, but she found they only succeeded in making her stand out from everyone else. She recalls that the accompanying gas bottle was bulky and, “They made a very big noise and everybody used to stare at you when you opened and shut your hand.”

It’s no surprise that some of the children found ways of rebelling against the use of prostheses. Ed attended the occupational therapy centre at Roehampton, where the children practised using their artificial arms for everyday activities such as eating. But they struggled to get food into their mouths using the prosthetics and were left “starving hungry”.

As soon as the therapist left the room Ed and his companions removed the prosthetics and happily ate using their own hands, feet or straight from the plate. The prosthetics were quickly replaced before the therapist returned to praise them for doing so well with their artificial arms.

Adapting to fashion

Clothes were another way in which disabled bodies could be ‘disguised’ in order to fit in with ‘normal life’. There are lots of stories of girls wearing shawls and capes, both very fashionable in the 1970s, in order to cover their upper body. But teenagers also wanted to be able to dress like their peers, and the more enterprising found ways to adapt fashionable clothes to fit their bodies.

Carolyn wearing a school coat, traditional for the time, that her mother had adapted to be functional for Carolyn’s body.

Hitting their teens raised other issues for thalidomide survivors. Being fitted for prosthetic limbs could be a humiliating process when it involved standing or lying still for long periods of time in underwear while measurements and casts were taken.

Some children built strong relationships with limb-fitters whom they had been seeing for years. Tracey persuaded her limb-fitter, Fred, to make her some legs with feet that would fit the high-heeled shoes that she craved. But when she walked into the doctor’s office proudly wearing four-inch stiletto heels, the doctor said: “I’ll give you three weeks walking around on them.” And poor Fred got into trouble when she admitted that she’d already been walking in them for three months.

Freedom in a wheelchair

For four-limb-impaired thalidomide survivors who had rejected prostheses, and those with more extensive lower-limb impairments, the arrival of electric wheelchairs was their first opportunity for independence. When Rosie was 14 years old, she commandeered a spare electric wheelchair on a visit to the Nuffield Orthopaedic Hospital and was “liberated”. She describes how, “I could get where I wanted to get without being exhausted and at warp speed, which I’d never experienced before. This was brilliant!”

As thalidomide survivors grew from young children into adults, they gradually found their own ways of adapting to fit in with a largely able-bodied world, shaking off the expectations of visual ‘normality’ and making their own choices about the devices and ‘enhancements’ that they found useful.

About the contributors

Ruth Blue

Dr Ruth Blue is a freelance writer, researcher and oral historian with a PhD in fine art from the Slade School of Fine Art. She worked for Wellcome for 17 years, where she began working with thalidomide survivors in 2013, collecting their stories, photographs and artefacts. She has continued this work for the Thalidomide Society.

Hollie Chastain

Hollie Chastain is a mixed-media artist and award-winning illustrator living and working in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Coming from both a graphic-design and studio-art background, her work has a storytelling quality, mixing found material, strong graphic elements and modern palettes. Along with gallery work, she has illustrated work for Smithsonian Magazine, Warner Music and the Oxford American, among others, and authored and illustrated a book published in 2017. She currently works from a home studio with her husband Eric, two children, two cats and two dogs.