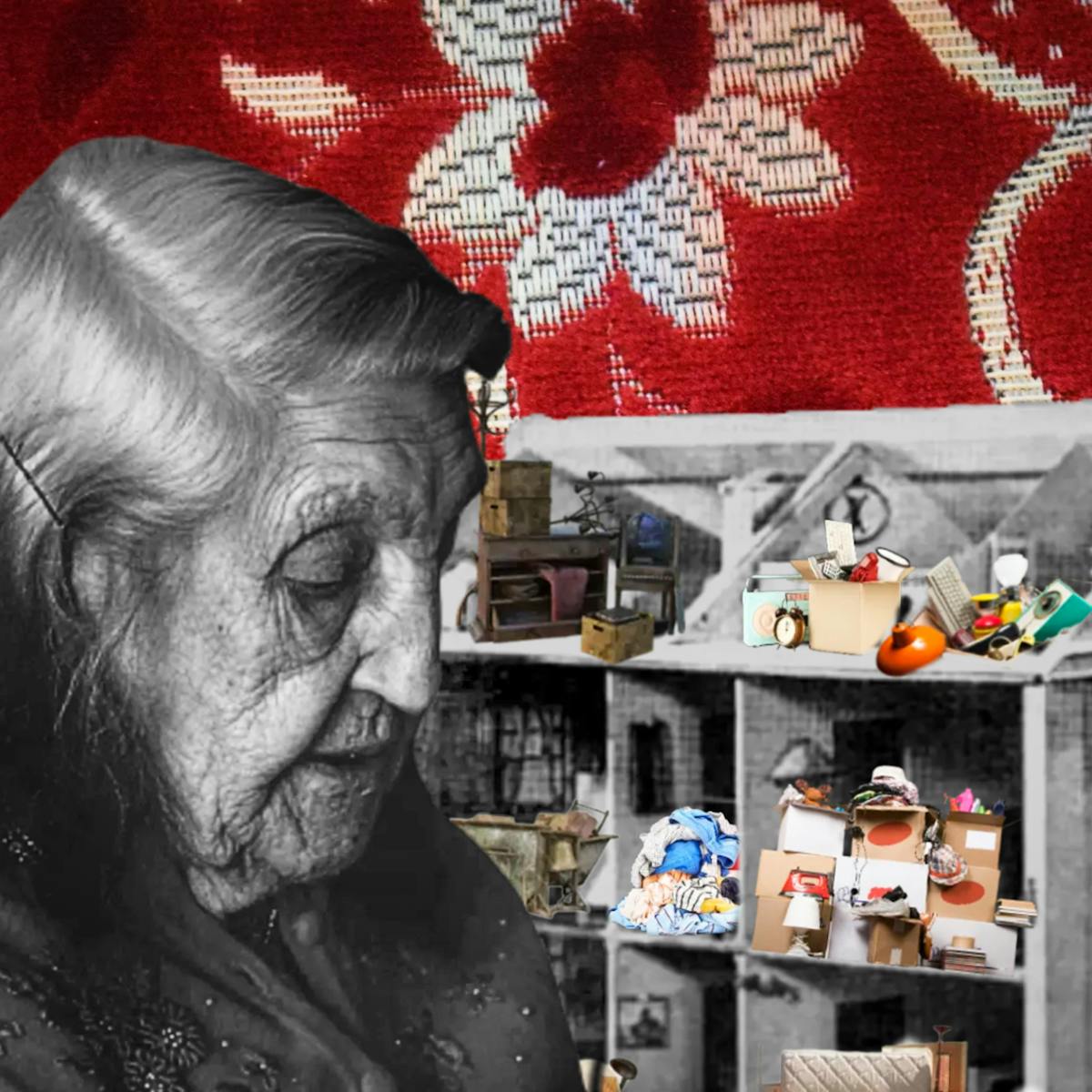

The small bungalow where Georgie Evans’s grandma lived was overwhelmed with stuff, and Grandma seemed intent on gathering more. Witnessing her grandma’s frustration, and the increasing danger the piles of clutter presented, Georgie embarked on a series of articles, hoping to understand hoarding behaviour, and to explore the literature, language and science surrounding it.

I’d visited Grandma in her bungalow at least once a week for as long as I could remember. Almost every time, she’d be sitting in her armchair when we arrived, reading, or watching telly, or looking at the street outside.

On one visit in particular, we found her in the front room, throwing things around. I say throwing; what I mean is, she was taking things from one pile and chucking them feebly on to another. “It’s here somewhere,” she kept saying. “I know it’s here somewhere.” She did this, despite my protests, for at least 15 minutes.

Finally she wondered aloud if the TV remote might be in the bathroom. When she stood up, a fuss of receipts, tissues, clip-on earrings and biscuit crumbs fell from her lap. I offered to check for her, but she was having none of it. So I watched, cringing, as she shuffled out of the front room, kicking aside magazines and shoes on her way. I worried she was going to trip and fall.

Without Grandma busy in her chair, the room changed. It made less sense. When she was gone, the bungalow became strange and looming.

It was like that because my grandma hoarded. She collected and stashed things, and it was almost impossible to convince her to throw anything away. She lived in defence of her belongings, trying to persuade us that she needed every single thing she owned.

There was no order – none that made sense to me – to the way she stored these objects. She bought and bought, and what she bought yesterday would soon merge into the blur of items that had grown into mountains throughout the bungalow.

“There was no order – none that made sense to me – to the way she stored these objects.”

Boxes, clocks and remote controls

From the small stool I found to sit on, I spotted the TV remote: on the windowsill, half-hidden behind a framed photograph of my cousins. I went through to the bathroom and tapped Grandma on the shoulder. “I’ve found it,” I mouthed to her. She read my lips, and nodded; she got it. Slowly, I led her back to her armchair, and when she was settled and I knew she wouldn’t fall, I reached over some precariously stacked jewellery boxes to claim the remote.

“What’s it doing there?” is all she could say. We laughed. And finally, I could mute the telly. She would put the volume on full blast sometimes, hoping that if it were loud enough, she’d be able to hear it.

Grandma had been deaf since she was a child, but I hated having to remind her: dementia was making her forget. When I told her, she always rubbed behind her ears. She didn’t always believe me. It was the reason she collected alarm clocks; she was sure that if she could find the right clock, if she could get it to ring loudly enough, she’d be able to hear it.

Writing about Grandma

When I asked Grandma, years later, if I could write about her, she gasped. “You want to write about me?” I nodded, smiling back. I said, “Can I write about your stuff?” As she read the words on my lips, her own mouth moved in imitation. “My what?” I repeated the word. She said, “Stove?”

“There must be a reason why, all these years, I’ve thought of my grandma as a hoarder.”

I laughed and shook my head. I gestured around, at the room that was swollen with objects. “Stuff,” I said, “your stuff.” She looked from my mouth to my hands to the piles of clothes they pointed towards, her brow still furrowed. I’d never used the word ‘hoard’.

She kept forming words on her lips; I kept repeating mine. Then she got it. She said yes, of course I could write about it. “But I don’t know why you’re interested.”

When collecting becomes hoarding

In the room in which I am writing, there are two full bookcases, three bags for life spilling books, and more piles of novels on my desk, my chair, on top of the wardrobe. It seems I’m a collector. But… I’m not a hoarder. No one would think I was hoarding because I have too many books for my shelves.

Why? Is it because other people see value in my books, whereas what Grandma collected appeared to be simply rubbish?

I wish I knew more, and could understand the shape and form of hoarding. There must be distinctions and hard lines. There must be a reason why, all these years, I’ve thought of my grandma as a hoarder. At what point did she cross over, shift into that group? I suspect it was the point at which her home became unsafe to live in.

I want to understand all the things I didn’t when I was younger, and Grandma’s bungalow was at its fullest. In this series, I’ll tackle hoarding from all angles: the science, the language, the literature, the perception, and how these things characterise my grandma’s experience. Because something I thought was simple seems more complex every time I delve into it.

About the contributors

Georgie Evans

Georgie Evans is a writer and bookseller from Halifax. She has an MA from Goldsmiths University and has published words in Brixton Review of Books, the Rialto, the Pomegranate, and the Telegraph. She is currently working on a hybrid non-fiction book about deafness and dementia.

Nicole Coffield

Nicole Coffield, also known as Collage Graduate, is a digital collage artist based in Northern California. Her work is composed of forgotten ads and images that are reworked to tell a new story.