In November 2017, Gaia Pope, a teenager who had been failed by the justice and mental health systems, went missing. Her body was found after 11 days. Here, her cousin Marienna Pope-Weidemann proposes compassionate systems that listen to those in mental distress.

A story of death, trauma and austerity

Words by Marienna Pope-Weidemannaverage reading time 11 minutes

- Article

Content warning: Sexual violence, mental distress, loss. The day Gaia went missing, the world turned upside down. That was almost two years ago and it’s still not close to right side up. Gaia was the light of our lives. She was also a survivor of sexual violence, denied justice and ultimately killed by the very system that is meant to protect and care for us.

Dorset Police failed to prosecute her rapist – a known child sex offender – and convinced her not to appeal. Like so many, she was also let down by the mental health system, which detained and then abandoned her. On 7 November 2017, Gaia disappeared. After 11 relentless days, she was found dead on a coastal path near our home. She was 19 years old. The coroner ruled the cause of death as hypothermia; we call it a death by indifference.

Gaia’s story captured national attention because it speaks to a whole generation who know the horror of being denied justice after abuse; the pain of finding the courage to ask for help and then being ignored; the humiliation of being interrogated and stripped of the financial support we depend on.

I write this from the perspective of someone with five years’ experience caring and advocating for loved ones enduring extreme mental distress and as someone with my own lived experience. These two perspectives aren’t separate for me, or for countless others: both are rooted in the realities of poverty and oppression.

Gaia Pope, photographed by Marienna.

The nightmare

I often have nightmares. There’s one that repeats a lot, something between a nightmare, a memory and a fear for the future. The life of someone I love is in imminent danger. I am in a softly lit room, phone in hand. All I have to do is call a number, a very important number, and the system will spring into action and take care of us.

I call. It rings. No answer. I call again. “I’m sorry, we’re unable to get to the phone right now,” says the voicemail. “We are only open between blah and blah o’clock.” But it is between the hours of blah and blah. I call again, and again. The light starts to flicker.

Icy panic flushes through my limbs and pulls down on my organs, like when you crest the summit of a rollercoaster. I start calling other numbers; I’ve got at least 25 of them in my phone, different doctors and nurses and teams, because this person that I love has been passed from one acronym to another for a long time and the numbers have really stacked up by this point, but not one of them will answer me. The room darkens.

Finally, a human voice greets me with a surreal neutrality. I take a deep breath, push down all my desperation and anger over broken promises, knowing that if I show any emotion I’ll just be told to calm down. I try not to focus on the irony of the fact that I’ve learned not to show any signs of mental distress when dealing with professionals whose job it is to support those experiencing mental distress because I know they will dismiss me. I tell them we’re in crisis, we need those plans and promises fulfilled.

An approach that values lived experience is vital not just for those using the system, but for fixing the system itself.

I use all the right acronyms, all the right words, like “safeguarding” and “imminent risk”. You have to use their language. It’s like talking to a really primitive version of Alexa. The voice tells me they won’t be sending anyone to help. It tells me it has no record of any promises made and not to call again because I’m making a nuisance of myself. Now I’m in total darkness.

All dignity evaporates and I start to beg – not for the first time. Please. Someone is going to die. Please do something, please. Help us. The voice says something about a week next Tuesday. I tell them that’s too late. The voice asks me how I dare tell it how to do its job. It tells me that if I ring again, the police will be called, then hangs up.

I wake with incalculable rage heaving in my chest. I summon the energy to sob, just to get out some of the adrenaline.

I know the dream will follow me all day like a dark cloud. I know I’ll jump at loud noises, stare into space, compulsively pore over some records for no particular reason other than to remind myself that all these things actually happened.

Bad things happened, no one came, and Gaia died; and those of us left behind, stumbling under the weight of our grief, must still depend on the system that let her die; that has let many people die.

Floral tribute to Gaia.

Sharing stories

It is extremely difficult for carers to speak out. We too are dependent on mental health services. When you’re starving, you don’t bite the hand that feeds you, even if it’s only tossing you crumbs.

Five years engaging with community and residential mental health services has taught me that ‘family engagement’ is usually an outsourcing programme. There are rare exceptions – shining lights in the darkness – but they are bound and gagged by the system they work in and often burn out. The rest talk to you like they know everything and you know nothing, not even about your own pain, your own family.

It’s taken me a long time to grapple with the reality that I might need support myself. In my mind I was the advocate. I hid away in that role, trapped in the same soundproof box I built for myself when Gaia was missing, and I spent every hour of the day organising searches and giving interviews so I wouldn’t have to stop and hear the screaming silence of the absence of her voice.

Part of what gave me the courage to acknowledge my own pain, my own story, was the stories shared by others. They started coming through a couple of months after the Find Gaia Facebook group became Justice for Gaia, highlighting the intersectional links between austerity, inequality and sexual and domestic violence. I was speaking and reaching out because I wanted Gaia to be heard, and soon people started talking back.

“My dad tried to throw himself off our balcony, and two years later he’s still on the waiting list. I’m afraid to leave him alone.”

“I was raped by a colleague and my boss has threatened me with disciplinary action if I speak out or access counselling.”

“I’m fighting for an inquest for my teenage daughter who died a preventable death in a secure mental health unit, but I can’t afford a lawyer.”

“My grandchildren are being beaten at home. I’ve got stacks of evidence here, but I’m being ignored by social services and threatened by the police.”

That was when I realised how many of us are trapped in this nightmare together. I’ve been involved in anti-austerity campaigns for almost a decade, so I thought I knew how bad things were, but I was wrong.

Since 2010, several billion pounds’ worth of cuts to essential health and social services have been linked to over 120,000 deaths in the UK; I thought funding was the issue, but I was wrong about that too. Austerity only explains why the capacity of mental health services to help has been crippled, especially for marginalised communities, young people and rural dwellers. What it does not explain is why these services so often do active harm. This is an issue with roots far deeper than Tory austerity.

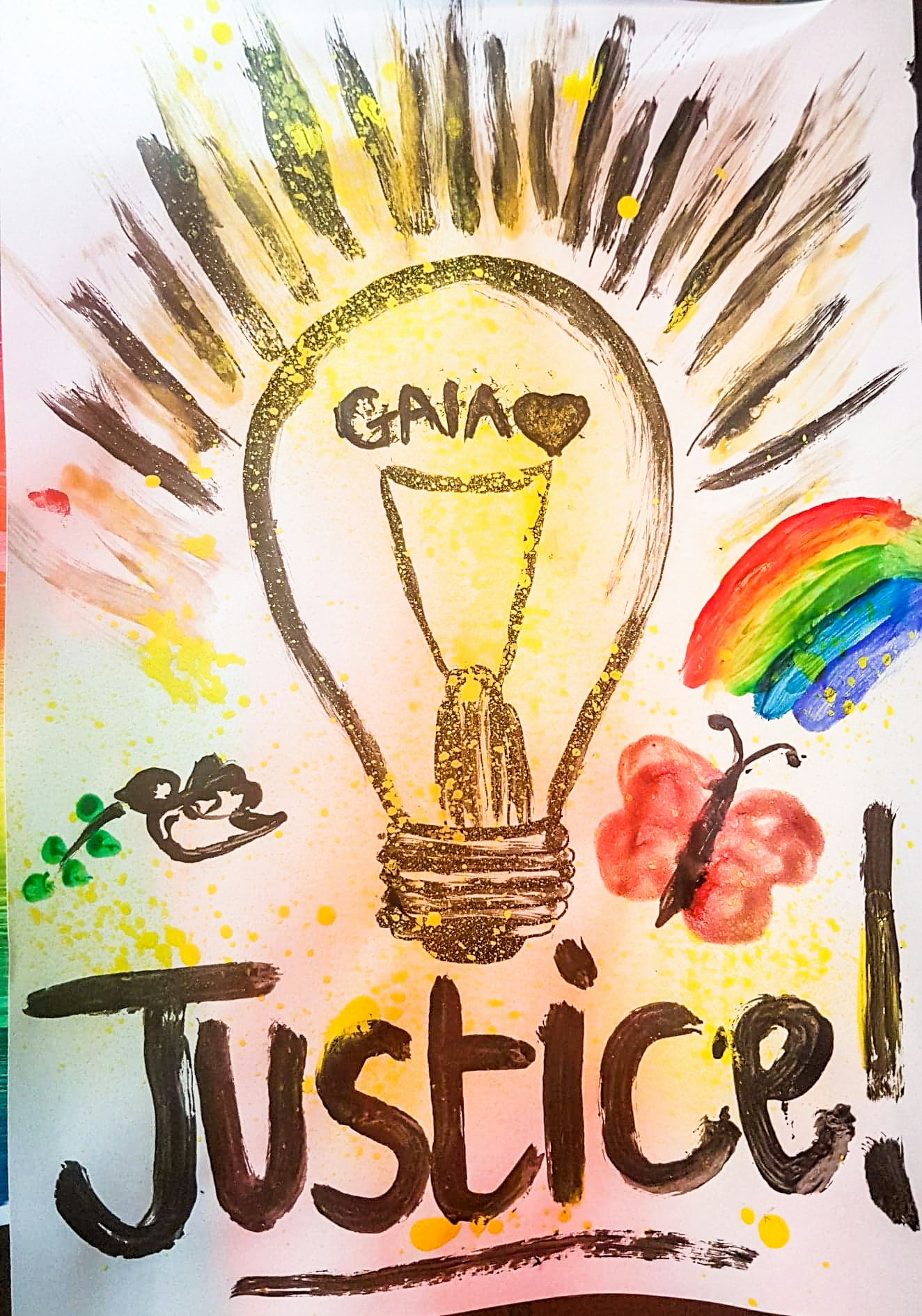

Artwork for Gaia.

An unjust reality

Evidence for the central role of trauma in mental health problems is overwhelming. There is a reason we are seeing a Black mental health crisis, with people of colour more likely to be sectioned, overmedicated and assaulted by those meant to care for them. There is a reason why almost half of women who have endured severe mental distress are survivors of sexual violence. There is a reason why almost half of those in need of benefits and half of those in financial debt are struggling with their mental health.

The common thread is trauma, the impact of which is magnified not just by austerity, but also by a mental health system, which, while essential, is as unequal as the rest of society.

Last year, I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Gaia suffered from severe PTSD, so I recognised the escalating cycle of insomnia, sleep disturbances, panic attacks and flashbacks that had already pushed me out of two jobs, my relationship and my home.

PTSD means the brain is more sensitive to certain trauma-related stimuli. There’s no doubt that my brain works differently from the way it did before Gaia was taken from us. I metamorphosed from a confident, fearless and idealistic young professional to an insular, nervous wreck, unemployed and too exhausted to even apply for the benefits I was entitled to. I couldn’t bear to be told by one more person that my pain wasn’t worth anything, as have 125,000 others with mental health conditions who’ve had their benefits slashed.

Did I suffer these symptoms because my brain is dysfunctional, as the medical model says (this is a widely followed theory that views mental health problems as physical illnesses, treating them with medication)? Was I broken by what happened? Or, after the trauma, did my brain adapt to a learned reality that we are living in an unjust world where the unthinkable can happen?

It might not seem an important distinction, but knowing, loving and losing Gaia – whose trauma was incalculably greater than my own – has taught me just how important that question is.

If my brain is to blame, I am what is broken here. The medical model justifies medicating people so they live and work obediently in an unjust world. It is the psychological equivalent of smashing square pegs into round holes until they fit – even if you break them in the process. There’s a strong financial incentive for this because drugs are cheaper than talking therapy. That’s where austerity comes in.

Maya, Marienna, Gaia’s mum Kim and Clara at Gaia’s festival fundraiser in 2018.

The oppressors and the oppressed

Like the murky inquest system we will have to navigate for the investigation into Gaia’s death, the medical model of mental health shifts accountability onto the oppressed and away from those oppressing them, whether that’s a family member or policymakers in government.

But if we take a trauma-informed approach, then the perpetrators of the trauma itself are to blame. They, and the systems that enabled their actions, can be held accountable. Whether that trauma is related to childhood or sexual abuse, hate crime and prejudice, structural racism, domestic violence, poverty or something else, suddenly your lived experience matters. An approach that values lived experience is vital not just for those using the system, but for fixing the system itself.

We are wired for connection. Little is more central to our wellbeing than a sense that we belong, that our experiences are valued, our stories heard. By pathologising symptoms that are most often caused by trauma, the medical model obscures our view of oppression, upholds the status quo and silences precisely the people we should be turning to for leadership: those with lived experience.

Some psychologists and users of mental health services are pushing for change. Mental distress – and the sharp learning curve that comes from any sustained engagement with the mental health system – can be a great teacher. Trauma can be a great teacher. But every day there are more deaths by indifference – another sibling, child or parent who has died waiting for someone to listen to their story. Dying along with them is the invaluable wisdom they’ve accumulated.

That I am slowly getting back on my feet is only thanks to the love and support of friends and family, and the inspiration Gaia gives me every day to keep speaking out. For me and many others the only thing standing between us and the void is the prospect of finally being heard, the possibility of change.

About the author

Marienna Pope-Weidemann

Marienna Pope-Weidemann is a writer and activist based in London. She leads the Justice for Gaia campaign on behalf of her family.