In the archives of Wellcome Collection is a fascinating medieval manuscript that provides instructions to take a remedy beyond medicine and into the realms of medieval magic. These portable step-by-step instructions help the would-be healer convincingly perform a healing ceremony.

A medieval guide to practical magic

Words by Rebecca J S Nicephotography by Thomas S G FarnettiMetalwork by Martin Hoptonaverage reading time 4 minutes

- Article

In medieval times, ritual and performance were part of everyday life, both as part of religious ceremonies, and in medicine and household duties. The mystery surrounding magic, with its sometimes forbidden and secretive nature, gives these rituals their allure, and practitioners were helped by rich visual tools, including tables, diagrams and charms in astrological, numerical, chiromancy and medical manuscripts.

One of these is Wellcome MS 407, a vellum (calfskin) manuscript from the early 15th century, with a collection of medical ‘receipts’ – or prescriptions – in English and Latin. I am going to focus on a short charm to be performed by the physician, which includes a mixture of religious, medical and classical references. In the margin, a template illustrates the object that the healer should make as part of the performance: a plate of lead.

Let’s consider this book as an everyday guide for magical, medical ritual, performed at the bedside. With its cheap and functional decoration highlighting some of the text, its size – small enough to hold and refer to – and use of the vernacular, this manuscript is all about function and portability. It was probably a tool for a physician looking to show off his status and education during a healing performance. The manuscript’s abbreviations and marginalia would have prompted the physician to follow the correct sequence as he worked.

Lots of medieval manuscripts have a similar type of feature text highlighted via rubrication (decoration) to help the reader to memorise or recite the words, but this manuscript goes further: the performance determines the design of the manuscript.

A modern reinterpretation of a medieval guide to practical magic

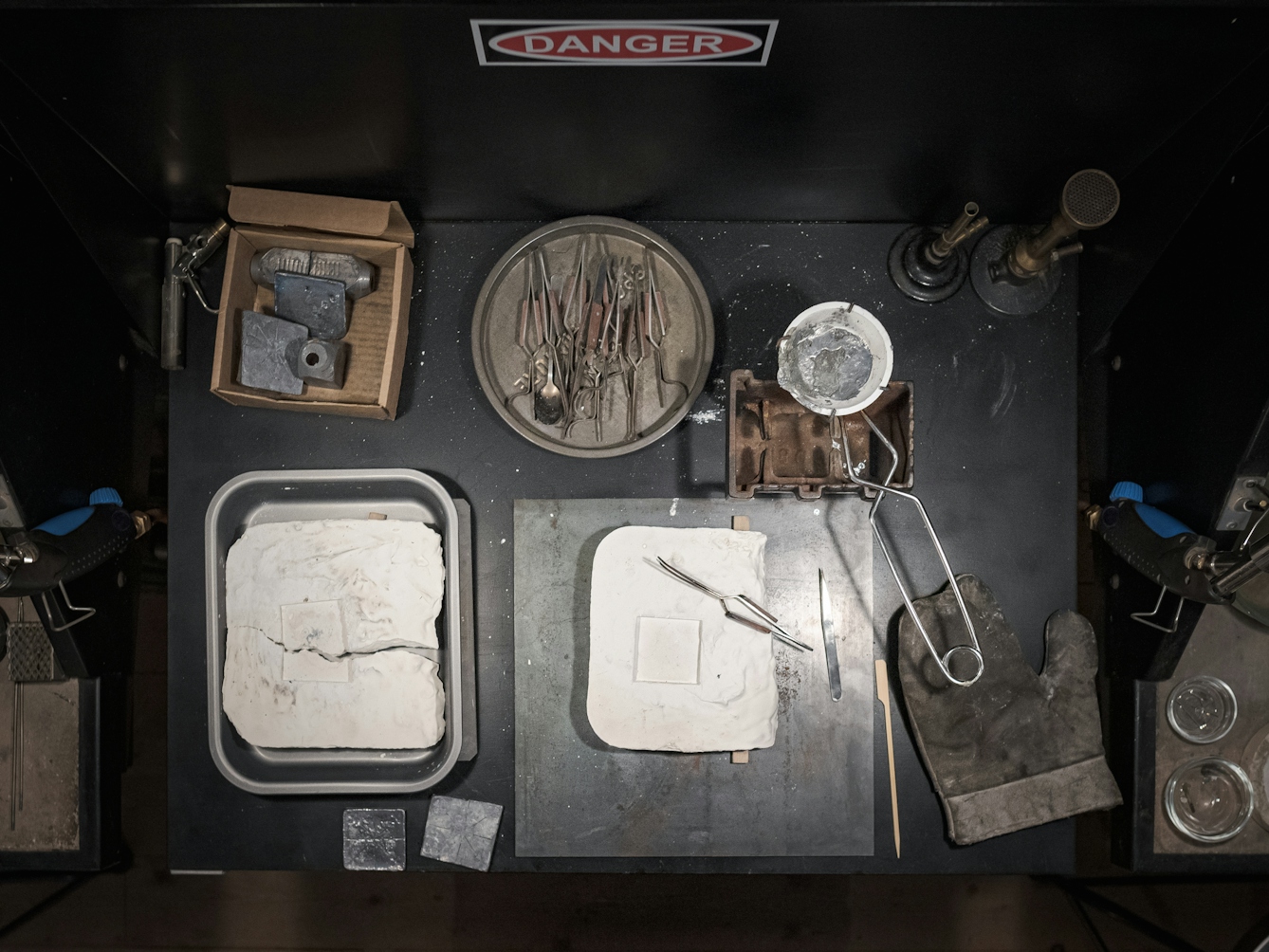

The specially crafted plaster-cast mould will be used to create the square healing plate.

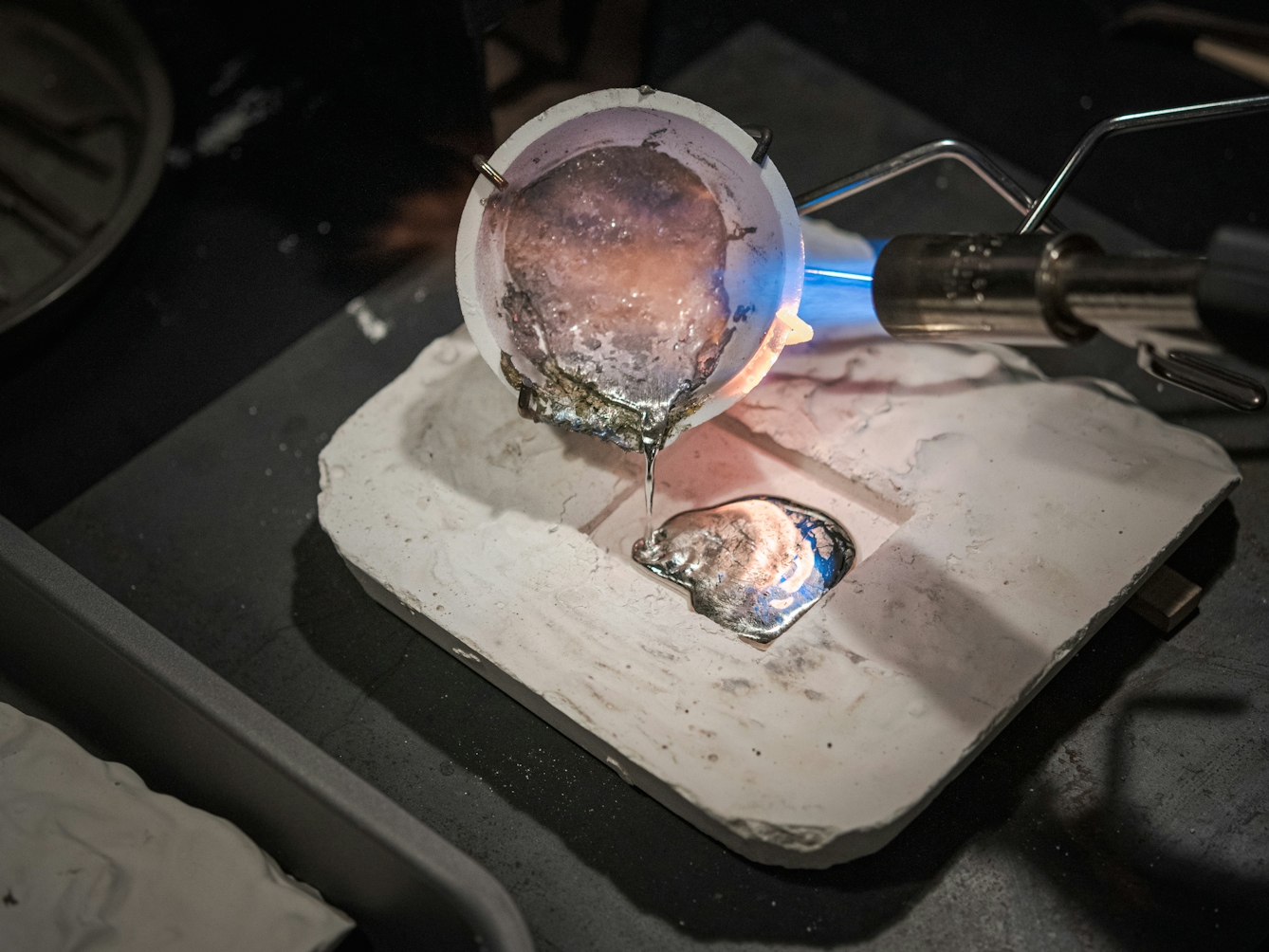

Martin heats the lead to its melting point of 327.5°C.

As the melting point is reached, the lead can be easily poured into the plaster mould. Due to its relatively low melting point, the flame is kept on the lead to help it retain its viscosity.

Once solidified, the lead can be easily removed from the cast. The plaster mould can be re-used a number of times to create additional plates.

The lead healing plate is set aside to cool. A thin oxide layer is visible on the surface of the lead after melting, giving off intense blue and purple hues.

Ritual and performance

A special part of MS 407’s design is the way it borrows contemporary written signs that would have indicated gestures, and alters them. For instance, the sign of the cross is part of the tradition of religious language, and in late medieval charms, crosses appear in multiples to tell the performer how many times to make the sign of the cross.

The charm with the lead plate in MS 407 is slightly different, though. It has crosses in the diagram instead of in the text, so that making the sign of the cross on the body is replaced by inscribing the plate. The crosses are transformed from something that simply provides timing and rhythm to something that is part of a performance and the making of an object.

Inscribing and blessing the object during the performance helps the patient to believe in its power to heal.

Imagine the injured person lying in bed while the physician attends them, book in hand. A fire is burning, with a basin of lead melting. The physician is instructed to inscribe the lead with five crosses while performing prayers. He then places the lead plate on the wound as the patient says five ‘Ave Marias’ and the physician reads prayers in Latin from the book. Inscribing and blessing the object during the performance helps the patient to believe in its power to heal.

Making the sign of the cross

The lines and crosses are made by pressing the lead with specially crafted sticks.

Martin carefully uses a wooden mallet to gently press the sticks into the lead.

The lead healing plate complete with five crosses and the tools to make the impressions.

Due to the malleable nature of lead, very little effort is needed to make the crosses. Four diagonally placed crosses in the four corners of the the plate, with leading lines to one central, right-way-up cross.

The lead healing plate would be placed on a wound which would be followed by the healing ritual. “The five inscribed crosses might represent the five wounds of Christ, allowing the patient to pretend that their wound is Christ’s wound, with a desired outcome of healing and resurrection...”

Master Craftsman; multi-disciplined jewellery maker Martin Hopton, of Martin Hopton Design and the Hopton & Furlong Workshop.

The performance provides a soothing meditative noise as the physician prays. Our patient contemplates the murmured words while gazing upon the crosses on the plate. They can recall those prayers again during the three days that the plate remains on their wound.

The five inscribed crosses might represent the five wounds of Christ, allowing the patient to pretend that their wound is Christ’s wound, with a desired outcome of healing and resurrection, so that they are physically mimicking Christ’s actions. The medieval person’s belief in the efficacy attributed to ritual objects has a close parallel in the modern-day placebo effect.

The designs of manuscripts speak a thousand words: this one – indicating a performance including creating an object with inscriptions, incantation and repetition – reveals almost as many actions and gives us a special insight into medieval healing practices.

About the contributors

Rebecca J S Nice

Rebecca J S Nice is an RCA/V&A postgraduate in History of Design and Material Culture. Building on a career as a dance teacher and theatre critic she now specialises in performance and object-based research, with a particular interest in ritual, performance and medieval manuscripts.

Thomas S G Farnetti

Thomas is a London-based photographer working for Wellcome. He thrives when collaborating on projects and visual stories. He hails from Italy via the North East of England.

Martin Hopton

Martin has many years of experience in the creation and design of unique jewellery, timepieces and accessories. His work, all designed and made at his Hertfordshire studio, combines the ingenuity of the Victorian Period, with an inherently gothic and dramatic style. He is co-founder of both Hopton & Furlong and St Albans School of Jewellery. He is a graduate of, and Associate Lecturer at Central St Martins, University of the Arts, London.