From animal-bladder skin to houndstooth check and sequins, face masks have undergone many revolutions in design over the centuries. Writer Lizzie Enfield traces their history in pictures.

Face coverings as a way of protecting respiratory health go back at least 2,000 years. The Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder (23–79 CE) used animal-bladder skins as masks to filter dust while crushing cinnabar, or mercuric sulphide, a toxic mineral used at the time for pigmentation in decorations.

In China there is evidence of similar face coverings dating back to the 13th-century Yuan dynasty. In his travelogue written during this period, the Italian explorer Marco Polo (1254–1324) described servants attending to the Chinese emperor and his entourage wearing silk scarves to cover their mouths and noses to prevent their breath from contaminating the food they prepared.

By the early 14th century, the Black Death, Europe’s largest plague epidemic, had prompted widespread use of facial coverings. Another outbreak in the 17th century led to the invention of the beak mask – which came to symbolise the plague – by French doctor Charles de Lorme. Covering the entire face, the mask had glass portals so the wearer could see, and the beak was often filled with spices or aromatics, including mint and camphor, to filter out disease.

Artist Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) soaked cloth in water and placed it on his face in order to prevent toxic chemicals from paint and plaster from entering his lungs. People trying to escape a burning building are still advised to use this effective method to protect their lungs from the effects of smoke inhalation.

The discovery in 1861 of the presence of bacteria in the air by Louis Pasteur made people aware of the dangers of breathing in harmful pathogens. This led doctors to prescribe cotton masks to limit contagion during epidemics. Fashionable women wore lace veils to protect their lungs from harmful airborne particles.

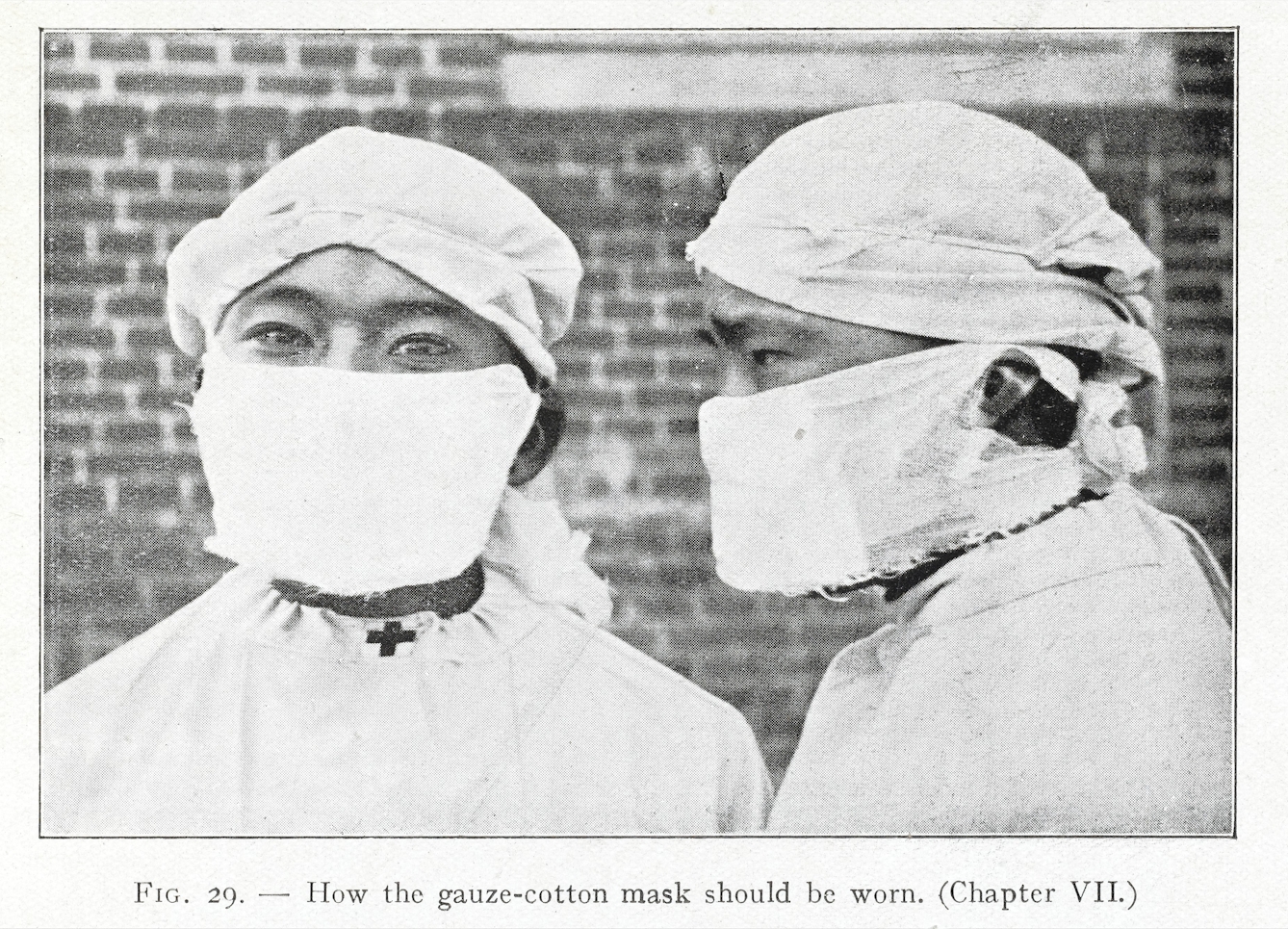

During the early years of the 20th century, Wu Lien-teh, a public-health specialist from Malaya, was investigating a pneumonic plague that had broken out in northern China. He developed a mask from layers of gauze enveloped in cotton, with ties so that it could be hung on the ears. This was the prototype from which the masks currently used in medicine today evolved.

In 1905 Chicago physician Alice Hamilton published a study about the amount of streptococci bacteria expelled when scarlet fever patients coughed or cried. She also measured the bacteria from healthy doctors and nurses when they talked or coughed, leading her to recommend masks during surgery. Her recommendations led to widespread use of protective masks for surgeons and nurses.

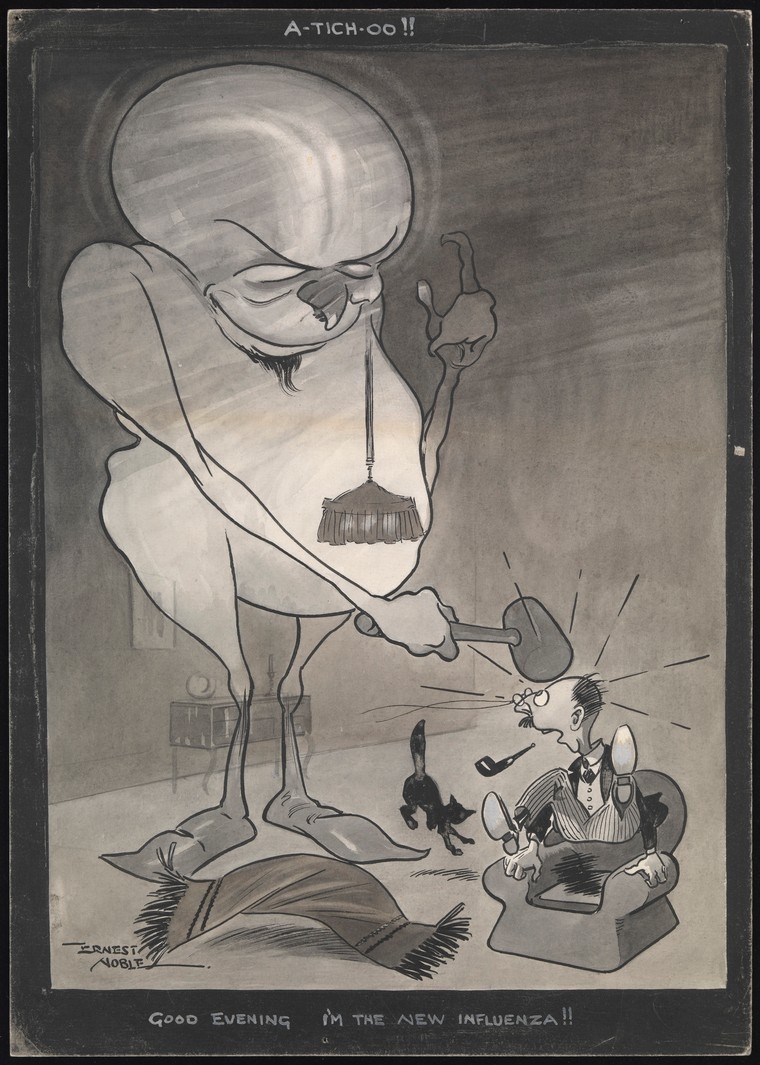

During the global flu pandemic of 1918, both medics and members of the public used protective masks, especially in America, where in some states they were compulsory in the workplace and on public transport. The virus personified in this drawing killed more people than World War I, which had only just ended when ‘Spanish’ flu emerged.

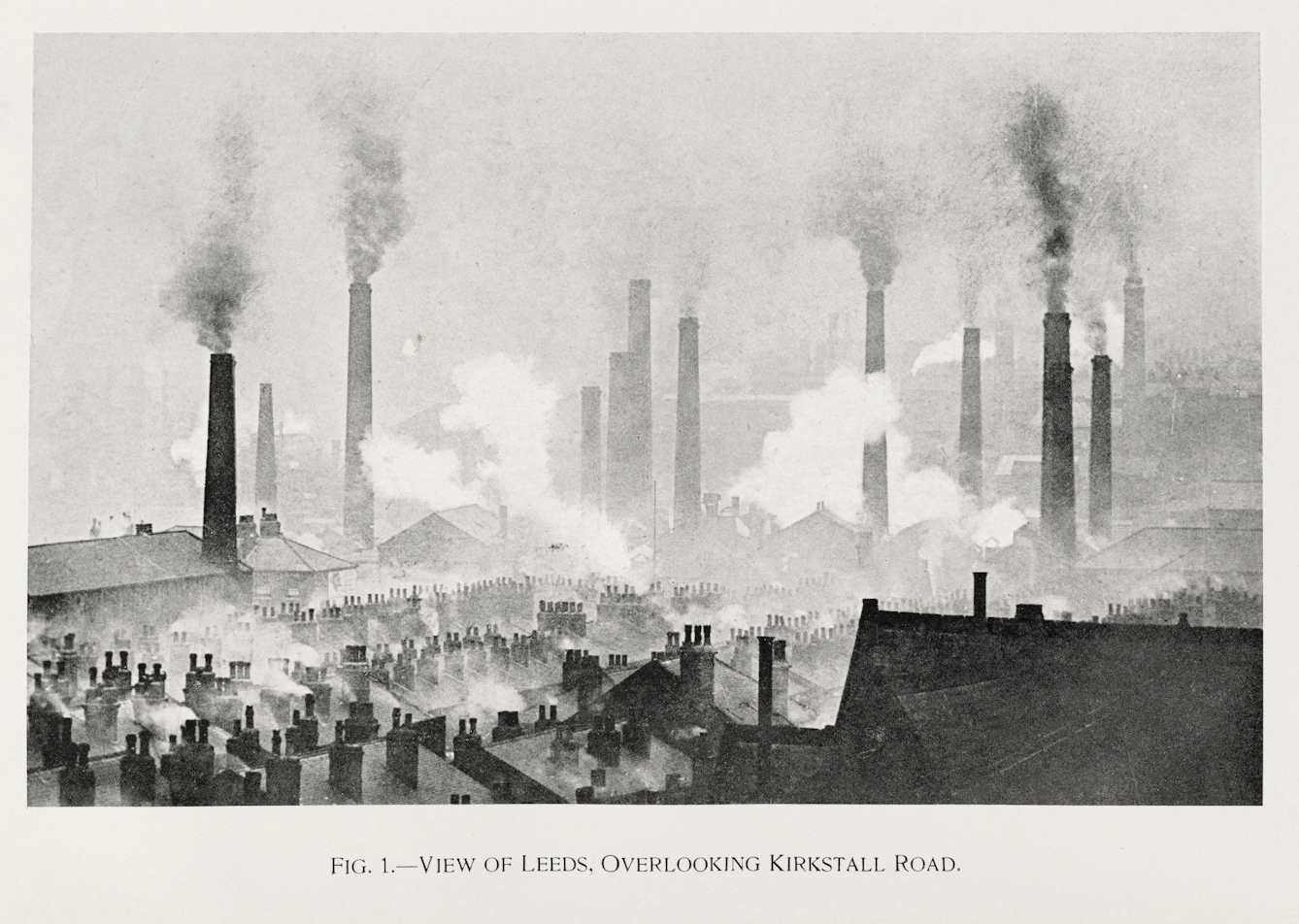

Increased industrialisation meant that by the 20th century one of the biggest threats to public health was air pollution. It led to people in some of the worst-affected cities adopting ‘smog masks’.

Early in 2020 French designer Marine Serre proved to be ahead of the game when, at Paris Fashion Week in February, her models wore outfits with matching face masks, designed months before the world became aware of COVID-19. But the fashion industry as a whole did not anticipate the demand to come, so the fashion-conscious have now turned instead to the home-sewn mask.

About the author

Lizzie Enfield

Lizzie Enfield is a journalist and regular contributor to national newspapers, magazines and radio. She has written five novels, and had her short stories broadcast on BBC Radio 4.