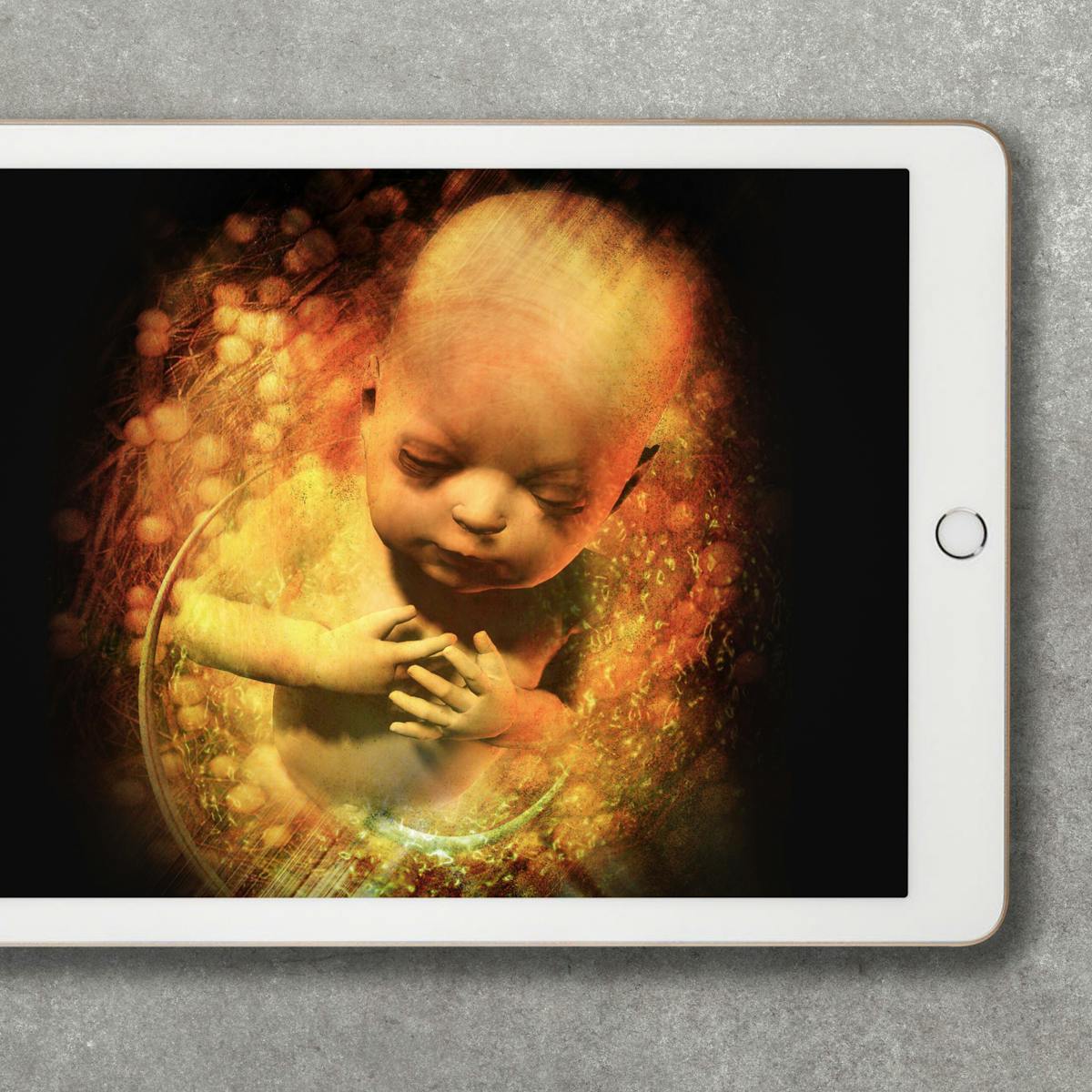

Will contemporary artificial wombs – which treat the premature baby not as an infant that has arrived too early but as a foetus yet to be born – face the same challenges as other revolutionary reproductive technologies? And what are we to make of the possibility that human gestation could one day occur outside the body? Claire Horn argues that, when it comes to imagining the future, the past offers some crucial clues about the different paths external gestation – ectogenesis – might take.

A history of gestation outside the body

Words by Claire Hornaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Article

For hundreds of years, pregnancy and birth were handled by women themselves, by female friends and relatives, and by lay midwives. Well before incubators were introduced as a medical technology, mothers and midwives had applied the common-sense notion that a newborn baby might best thrive in a closely swaddled, warm environment analogous to the womb.

For all that gestation was treated as a natural phenomenon, some women may have welcomed the help of ectogenesis. Childbirth remained dangerous and there were limited avenues for care when something went wrong. We have long used scientific and medical advancements to make other ‘natural’ things easier and less painful. Why not gestation and birth too?

Perhaps the earliest vision of artificial human gestation comes in the form of the homunculi imagined by alchemists in the 1500s. In his 1572 ‘De Natura Rerum’, Paracelsus insisted that he had developed a guide to creating a miniature infant (a homunculus, or “little man”). If one put sperm in a flask alongside horse manure and ‘fed’ it blood, he wrote, a small human form would appear, translucent at first but growing more solid over the next 40 days.

The notion that humans existed as very tiny persons within sperm, popularised in the 1600s, essentially regarded the pregnant person as a vessel that could easily be swapped for another mammalian uterus or even a beaker. The first fantasy of ectogenesis, then, was as a means of men seizing control of reproduction, making sense of the elusive, dark space of the womb by replacing it entirely.

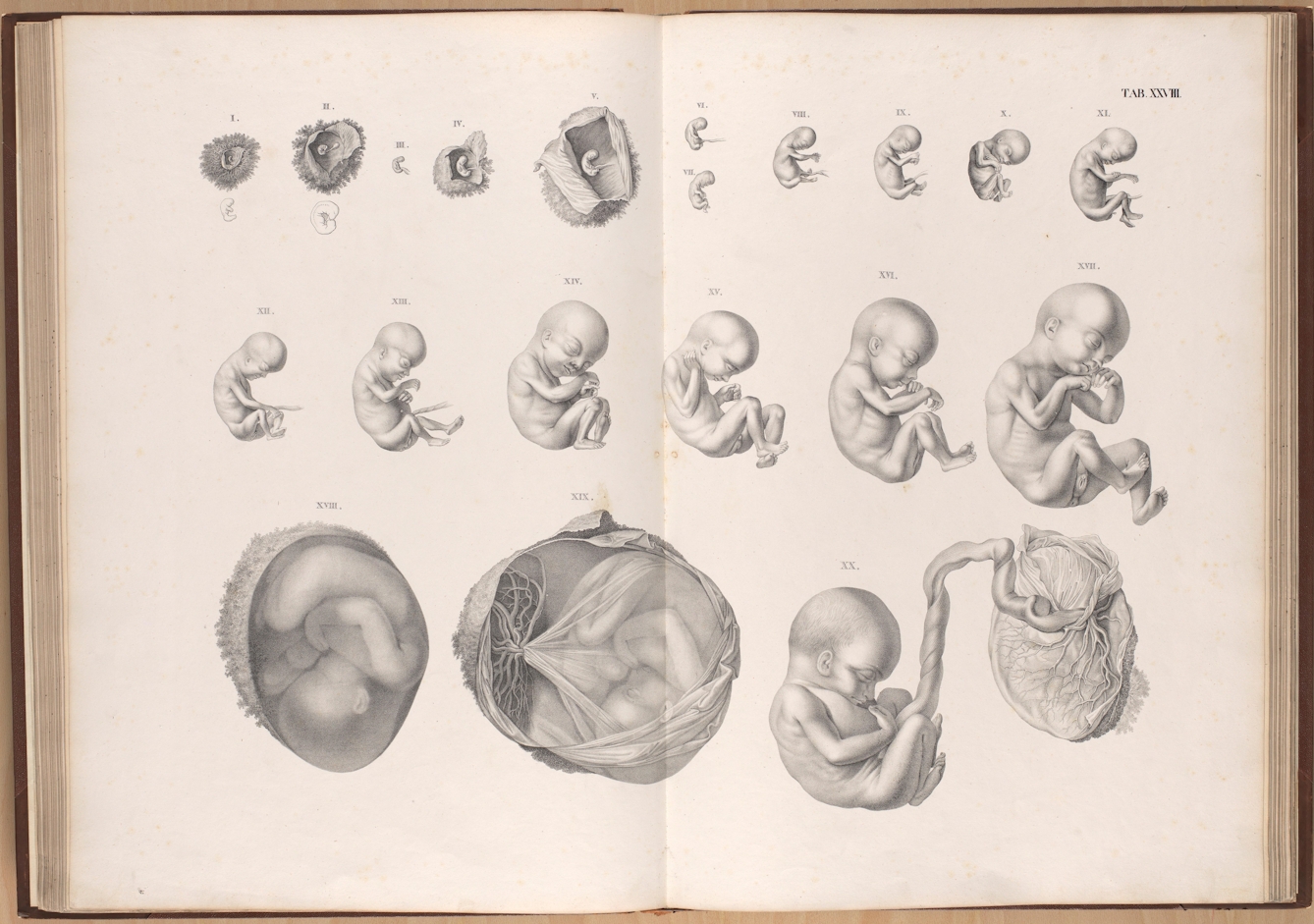

In the late 19th century, the field of obstetrics developed in earnest as doctors became interested in bringing pregnancy and childbirth under their purview. Physicians (mostly men) and formally trained male midwives began to codify what was ‘normal’ in pregnancy, rendering both gestation and birth medical concerns.

The coming decades brought means of measurement and risk management, but many of these methods, like the use of anaesthesia and routine episiotomy, were crafted to make things easier for the attending doctor, not for the person giving birth. Medical intervention is not inherently negative, and today, the care of healthcare professionals benefits many pregnant people around the world. The problem lies not with all technologies and interventions, but with how they are often used.

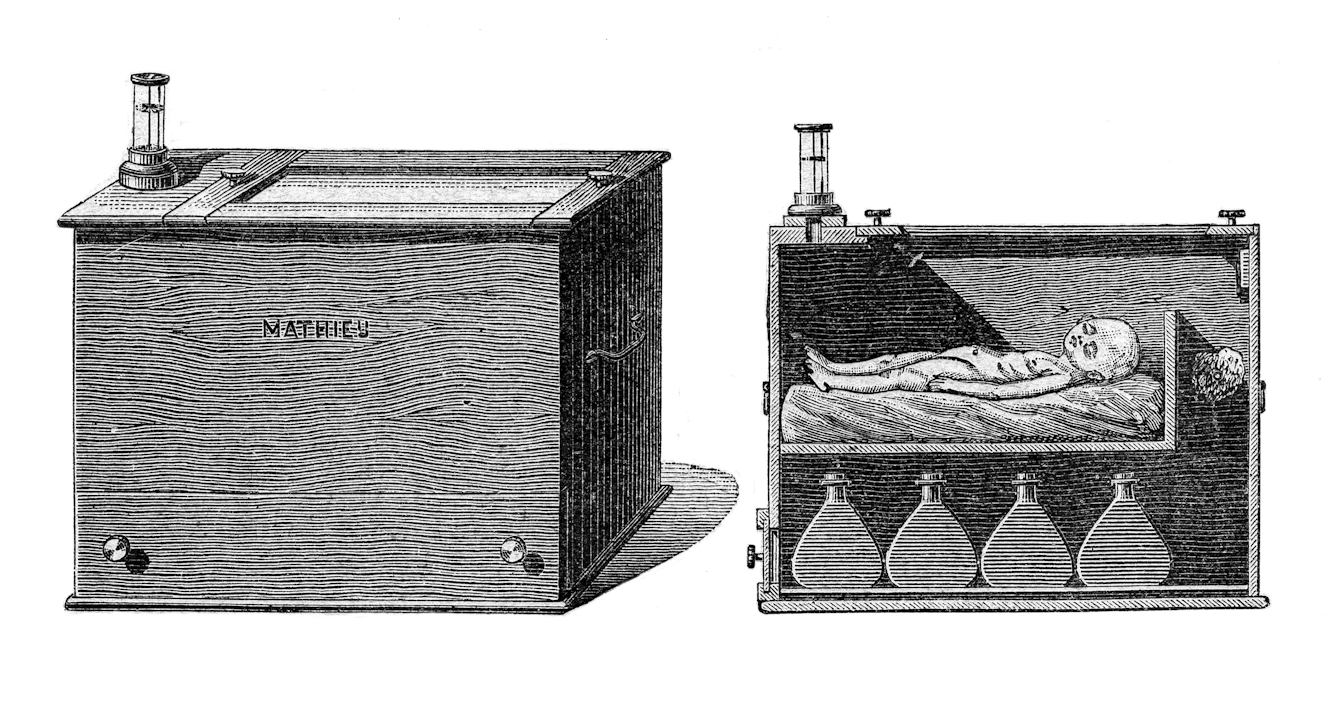

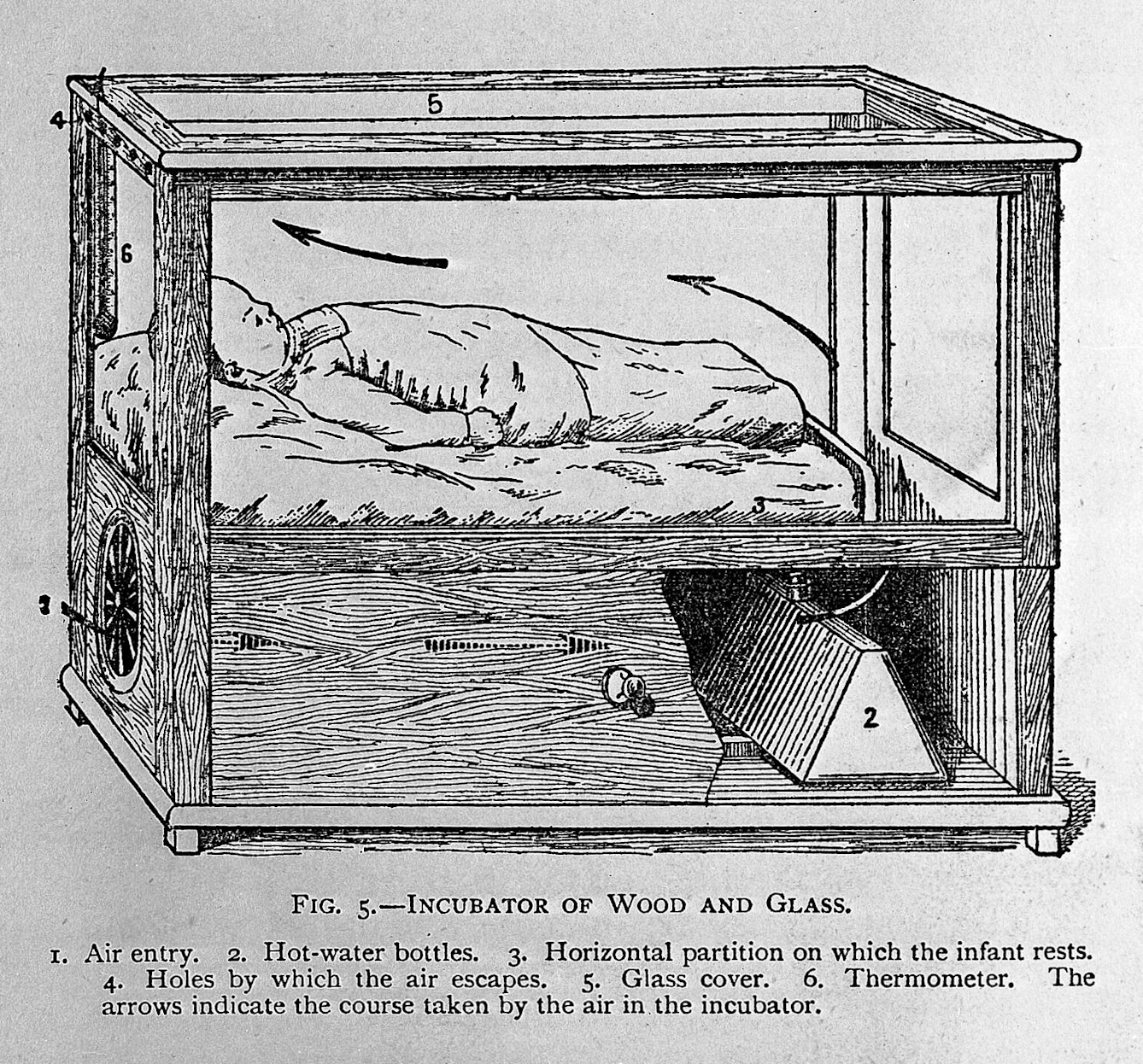

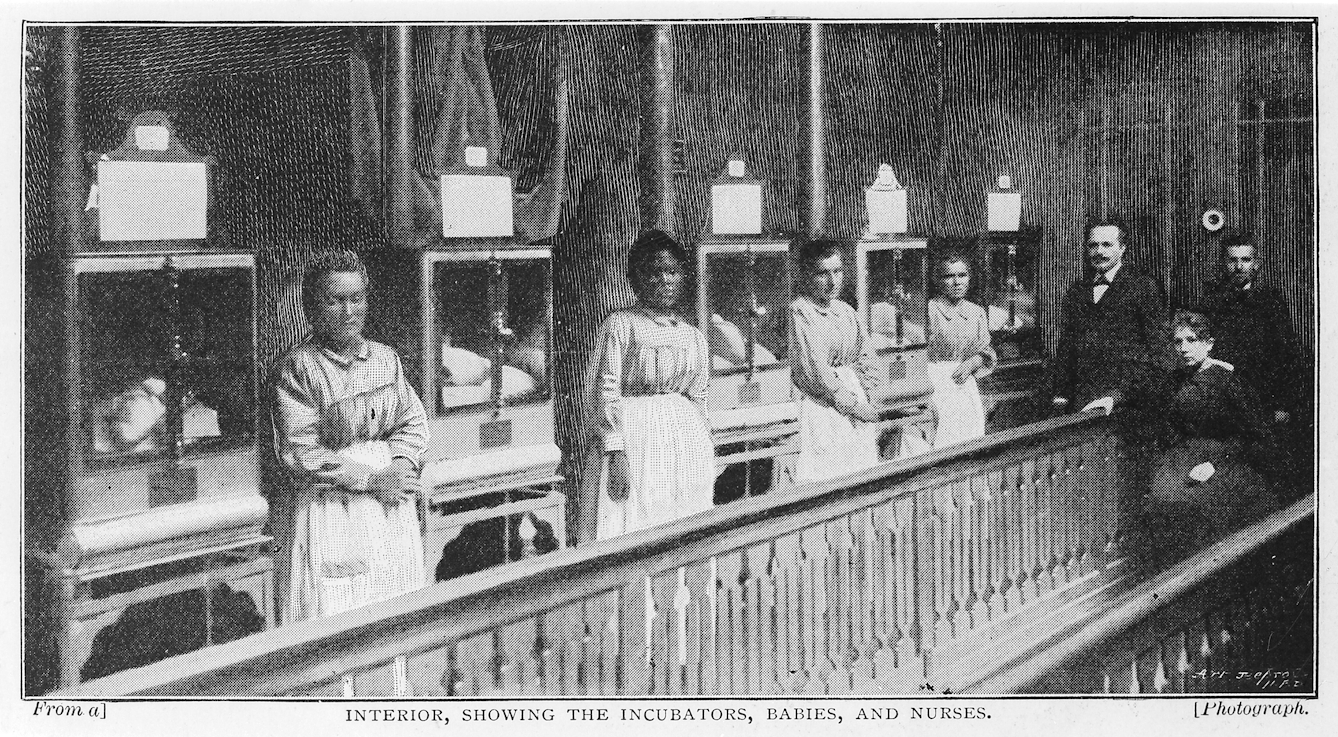

In the late 1880s physicians toured the first medicalised incubators – replete with live infants – across the World’s Fairs in Europe and the United States. Spectators paid to view babies ensconced in glass and displayed between rows of decorative palm trees. The exhibits generated speculation that human infants might be grown outside their mother’s bodies, much like orchids in the warm, humid environment of a greenhouse. These early incubators supported babies born not long before the 40 weeks that make a full-term pregnancy.

Just as pregnancy and birth had become concerns for mainstream medical practice, these new incubators initiated the idea of a premature infant as a special category of patient. In the leading medical journals, commentators debated the purpose and efficacy of the technology.

Some lauded its innovation but emphasised breastfeeding and closeness to the mother as superior strategies for the care of ailing infants. Others, however, wrote of the way the ‘orifices’ of the incubator were decidedly more pleasant to look at than the human uterus, and suggested that with its sanitised environment of air and glass, the incubator made a marked improvement on the mother’s body.

Those who believed the incubator might be an improvement on the human uterus were encouraged by the lofty claims of one of the technology’s creators, French physician Stéphane Tarnier, who claimed he was at the cusp of allowing the latter half of human gestation to occur outside the body.

The incubators produced by Tarnier and his colleagues were far from self-governing, requiring 24-hour maintenance, mostly performed by nurses. Visions of the technology as an autonomous object were quick to obscure the human caretakers in plain sight, and the incubator was even dubbed “an artificial foster mother” by one magazine reporter.

Debates over pregnancy, birth and contraception have loomed large across generations of feminism. It is no surprise, then, that artificial wombs have had a recurring place in feminist literature. The term ‘ectogenesis’ was first coined by the author and biologist J B S Haldane in a speculative speech given to the Cambridge Heretics Society in 1923.

Imagining that by the 1960s all babies would be born from artificial wombs, Haldane’s speech was later published as an essay, which prompted a series of responses from friends and colleagues. Among them was socialist feminist nurse and author Vera Brittain. In ‘Halcyon: Or the Future of Monogamy’, Brittain argued that artificial wombs were not the key to a future utopia. Instead, the path to a better future was one in which scientific progress would render birth and gestation safe and painless, and social progress would ensure that parents shared the work of childcare.

Shulamith Firestone, the Marxist feminist and author of the 1970s manifesto ‘The Dialectic of Sex’ is often misrepresented as an enthusiastic technopositivist who uncritically embraced ectogenesis. It is true that Firestone declared pregnancy to be barbaric, and that she argued “reproductive biology” was a tyranny that produced fundamental gendered inequity. There could be a world, she imagined, in which some form of artificial gestation could communise reproductive labour, redistributing the burden of gestating to the whole of society. But Firestone cautioned that “in the hands of current scientists, few of whom are feminist or even female”, ectogenesis should only be viewed with suspicion.

The sight of forceps or of a speculum can evoke fear and trauma for many people with vaginas and uteruses. J Marion Sims, the creator of the speculum and often dubbed the “father of gynecology”, was a white supremacist who cruelly trialled speculums and other interventions on Black teenagers without anaesthesia and without consent. Black women, Indigenous women, women of colour, people with disabilities and people living in poverty have been unjustly subjected to reproductive harms into the present day, from being denied sufficient access to safe and culturally responsive care to being targeted by eugenicists.

Modern-day feminist commentators on artificial wombs have rightly expressed concerns that this technology could be used to coerce and harm pregnant people, particularly those who are already marginalised in reproductive care. The legacy of intervention and technologies being used to visit obstetric violence on pregnant people is one in which ectogenesis is inevitably entangled.

Prototype technologies currently in development could allow infants to survive outside the human body in good health from as early as 21 to 23 weeks gestation. Popularly referred to as partial artificial wombs, they replicate the uterus by subsuming the extremely premature baby in artificial amniotic fluid and allowing it to continue to grow.

Embryological research has also made remarkable progress. In 2017, two teams of researchers successfully grew embryos in a laboratory setting up to the then limit of 14 days, demonstrating that human embryos could organise themselves without input from a person’s body for much longer than previously believed. In 2021, scientists at the Weizmann Institute announced that they had gestated mice from embryos into foetuses with fully formed organs, an experiment they hope to recreate with human embryos if ethics approval permits.

Researchers often draw careful boundaries around their advances, emphasising that artificial-womb technology will assist extremely preterm babies, not facilitate external gestation. But despite the caveats of their makers, these innovations have understandably raised excitement and concern about ethics and social implications.

Firestone was right to contend that what drives the creation of artificial gestation matters, and that it matters who technology is made by and for. As costly, resource-intensive treatments, artificial wombs are likely to only be available in highly equipped neonatal wards. But if they are successful in human trials, they stand to make a tangible difference for the families of extremely preterm babies who can access this form of care.

Media coverage that represents these technologies as a means of fully automating gestation is about as accurate as the news stories printed in response to the incubator’s arrival in the late 1880s. But what are we to make of the possibility that some (or perhaps one day, all) of human gestation could occur outside the body? The answer may depend on who has a say in the tech’s development, design and use.

Advanced-care specialists, parents, nurses, doulas and midwives are likely to have varied insights on how artificial wombs might most beneficially be applied. Imagine, for instance, an artificial womb that could easily be assembled in a low-resource environment or operated by a person in their own home.

These ideas may seem far-fetched, but the future of ectogenesis is unwritten. Hundreds of years ago, the vision of babies in incubators led Victorian spectators to imagine human life gestated like a rare flower. Drawing on the technologies in development today allows us to envision the as-yet-unwritten possibilities for our own future of birth.

About the author

Claire Horn

Claire Horn is a Killam postdoctoral research fellow at Dalhousie University’s Health Law Institute. Her work over the last six years has focused on law and policy governing sexual and reproductive health, rights and technologies. She has written for a variety of academic and nonfiction publications, including the Journal of Medical Ethics, the Medical Law Review, Feminist Legal Studies, Catalyst, Aeon, and Lady Science.