While recent research shows art in hospitals plays an active role in patients’ healing, its presence in medical buildings is nothing new. Art historian Anne Wallentine discusses why icons, frescoes, prints and sculpture have adorned the walls of wards and corridors for 600 years.

A history of art in hospitals

Words by Anne Wallentine

- In pictures

Some of my earliest memories are of the cheerful, colourful halls and playful sculptures in the children’s hospital where I was a patient. Decades later, I still remember the feelings of warmth and positivity they conveyed. In an environment often infected by fear, art provides distraction and comfort, contributing to the healing process – as it has, in various ways, for centuries.

In the Middle Ages, for instance, Christian religious communities provided care throughout Europe in hospitals which grew out of monasteries and convents. They were often decorated with biblical iconography, and included altarpieces and other devotional artwork. Here, care was intertwined with prayer.

In Italy in the 15th century, hospital artwork began to reflect the medical and charitable duties these institutions performed. Domenico di Bartolo’s fresco, pictured above, decorates the civic hospital in Siena with a detailed scene of the kinds of medical care undertaken there. The fresco was placed in the Pellegrinaio, which served as a reception hall and infirmary. Its prominent location emphasised the value of the hospital and its charitable work.

Early modern hospitals in Europe predominantly served people from poorer communities, as wealthy people could afford to be nursed at home. Manuscript and woodcut illustrations from the 16th century frequently depict plain, dark, busy wards with all activities — nursing, cooking, cleaning and eating — happening in a condensed space. Though some of this may be attributed to the compositional frame, many institutions with little funding would have been similarly crowded and undecorated.

At the other end of the spectrum is this painting from around 1598. It shows Elizabeth of Hungary, a patron saint of hospitals, who founded one of her own in 1228, tending to patients in a hospital space. With a Madonna and child sculpture and religious scenes framed above the beds, the intertwining of ideas about faith and healing is clear. St Elizabeth’s familial coat of arms is also set above the window.

Though the space is imagined, this painting illustrates what was likely an ideal version of a well-funded hospital of the era, which included religious imagery and donors’ arms to remind patients of the munificent sources of their care – in both the worldly and spiritual realms.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Scientific Revolution and Enlightenment sparked radical new conceptions of science, biology and medicine in Europe, bringing different frameworks to how hospitals were founded and run. Voluntary hospitals founded on Enlightenment ideals of education and scientific discovery began to replace those run by religious institutions.

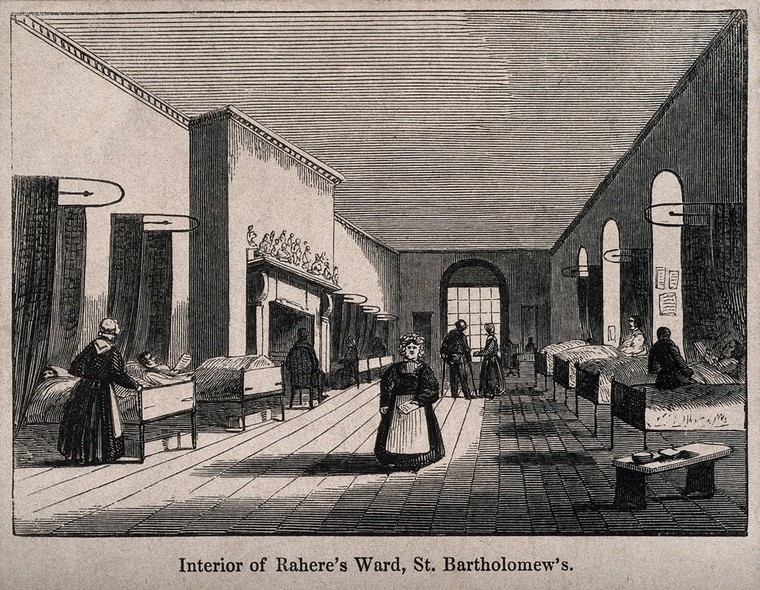

A contemporary illustration of Rahere Ward at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London shows a plain, repeating row of beds with curtains for privacy and professional staff consulting and monitoring the ward. There is some ornamentation above the fireplace mantel, but no religious or decorative imagery in sight.

Stark white walls – not unlike these – are my only recollection of the adult hospital I was diagnosed in before moving to the children’s hospital for treatment. When I visit hospitals now, I am always attuned to the contrast between generic, neutral-toned rooms and those with any kind of art or colour, which can make a strange environment feel that much more humane.

In the 18th century, the public and administrative areas of hospitals received more artistic attention to attract donors. Across Europe, hospitals for retired or ill soldiers also included triumphal battle scenes to glorify their sacrifices and a given political regime’s achievements.

While patients’ environments remained simple, St Bartholomew’s Hospital commissioned lavish artwork for its administrative wing, including a staircase painted by William Hogarth and the Great Hall, which featured the names and portraits of benefactors. Interestingly, Hogarth’s staircase, which would have been glimpsed by people seeking treatment, featured two biblical stories of healing rather than depictions of contemporary medical practice – perhaps aiming for the inspiration of allegory over visceral reality.

Though many institutions in the period added to their public and exterior decor, some began to challenge this use of funds. In 1755, the French priest Marc-Antoine Laugier advised that: “Hospitals should be solidly but simply built. There should be no building where sumptuousness runs contrary to propriety… Magnificence announces either superfluous funds in the foundation or very little economy in its administration.”

Public hospitals varied widely in their standards of care and cleanliness in the early 19th century. As nursing became professionalised following the Crimean War, efforts were made to instil more standardised practices as well as a sense of “middle-class respectability”. Hospital walls were often whitewashed to ensure any dirt would be visible, and an emphasis on good ventilation and frequent chemical cleaning became the norm.

While this era gave us our modern-day conception of hospitals as secular, sanitised, white-walled institutions, there was also a nurse-led emphasis on making the wards pleasant for long-term recovery. Original artwork could not withstand the rigorous cleaning protocols, but nurses sometimes hung glass-framed prints.

This photograph of antiseptic pioneer Joseph Lister in a men’s ward, from around 1890, shows the calm of a clean, organised ward of the era, with natural light, fresh air, and simply painted walls – and a few prints visible on the far walls.

Tile decor became popular in English hospitals around the turn of the century, as it was seen as more hygienic and convenient for frequent cleaning (and patronised Britain’s burgeoning tile industry). In 1901 and 1903, St Thomas’ Hospital in London installed tile artwork on the walls that featured characters from nursery rhymes and fairy tales in the children’s wards. Still, plain, standardised wards remained the norm, especially for adults.

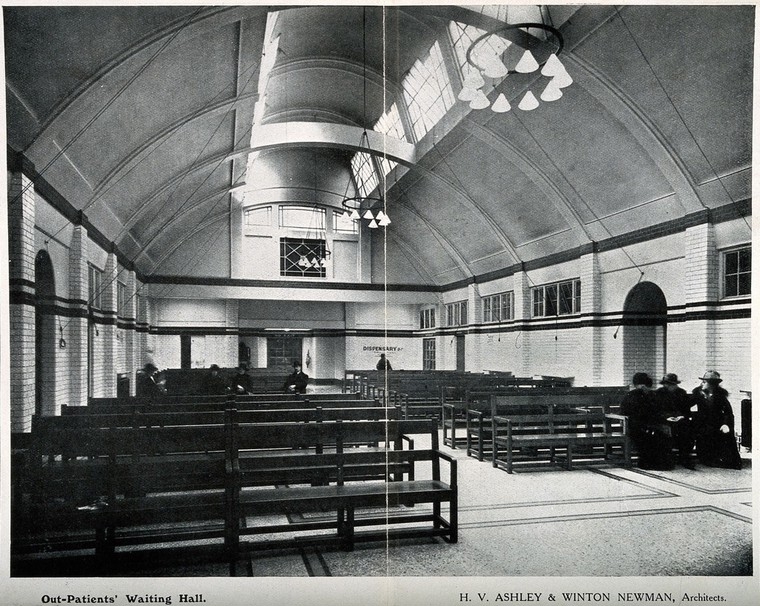

In 1913, the Royal Free Hospital’s bare, brick waiting room, shown above, appeared almost like a British Tube or train station, with simple directions to a dispensary marked on the wall at the back. The hospital’s maternity ward of the period was much the same: an undecorated room with regimented charts and lights above each bed. The contrast between the adults’ and the children’s wards of this era visualises our ever-evolving concepts about age and stages of life. At what point do we age out of needing visual or environmental comfort – or think we do?

In a hospital budget, art comes after the necessary medical tools and technologies – so it’s important to note who donated decoration, where, and why. Institutions with wealthy benefactors could afford grand commissions while many hospitals struggled to provide patients with the basics of care. As hospital art developed over the 20th century, wealthier hospitals, cities and countries were able to create art programmes and commission original art. Many others could not afford artistic additions or relied on the inexpensive simplicity of prints. But even a little bit of art could have an impact.

During World War I, trains, boats and residences were commandeered into makeshift hospitals. This 1915 painting shows recuperating soldiers in the lavish Music Room of the Brighton Royal Pavilion, which was temporarily converted into a hospital for Indian soldiers, with over 600 beds. The early 19th-century pavilion’s red and gold pseudo-Indian decor was not intended for a healthcare setting, nor for this audience, but served as an ironic backdrop to the segregation the Indian regiments experienced in the British Army, and their healthcare.

The choice of surroundings was not incidental – depictions of soldiers’ comfortable convalescence in photographs and paintings like this one were used as propaganda to convey the benevolence of colonial rule and stymie criticism from the Indian independence movement. The British also saw the Brighton Pavilion’s decor as ‘suitable’ for the soldiers recovering there, given its visual influences.

These images, as well as efforts to provide for soldiers’ religious practices and entertainment, were meant to inspire continued military recruitment by emphasising the government’s paternalistic concern for their wellbeing. The hospital’s gilded decor was, in this instance, a colonialist façade.

By contrast, this contemporary painting by official war artist John Lavery, copied by other artists, shows the first Caucasian wounded of the war receiving care in a typical ward in the London Hospital. The ward remains largely undecorated and true to the principles of the era, with plain walls and numbered beds. However, fresh flowers decorate the bedside tables in tribute, and a Union Jack hangs above a window as a propagandistic reminder of the origin of these injuries.

Flowers had been a popular hospital gift since the Victorian Flower Mission, which began in the 1880s. This charitable initiative in the US, Britain and Australia, delivered flowers to patients in an effort to brighten wards. Though less permanent than art – and more challenging for cleaning and maintenance – flowers were an easy yet significant way that impersonal wards could be humanised.

Josephine Tey’s novel ‘The Daughter of Time’ opens with a recuperating detective exasperatedly counting the cracks in the ceiling of his hospital room. Though his visitors bring him several kinds of flowers, it’s a print of a famous portrait that sparks his interest in solving another case. For me, at three and four years old, it was a small mountain of stuffed animals that provided the most cheering distraction.

Following World War I, the 20th century saw a flourishing of art collected or commissioned for hospital spaces across the western hemisphere. In the 1920s, the US Cleveland Clinic began hanging pictures to cheer up their patients, eventually founding a research institute to better understand art’s impact on health. Researchers have since reported that the clinic’s substantial collection of 21st-century art has a positive outcome on people’s health, with 73 per cent of visitors reporting improvements in mood, and 61 per cent reporting reduced stress because of it.

In the 1930s, the US Works Progress Administration (WPA) funded the creation of murals at hospitals and other civic spaces as part of their effort to provide jobs during the Great Depression. This initiative provided the seed for the NYC Health + Hospitals Art Collection, which is today the largest public art collection in New York City. As more studies began to show the numerous positive outcomes art can have on patients’ health, artwork and art programmes have become common in hospitals around the world.

In 1934, William Palmer’s figure-packed mural (above) valorised modern hospital care with a limited colour palette; almost a century later, the public mural programme in New York City’s hospitals has blossomed, with bold, primary colours and designs that range from cheerful abstraction to depictions of nature and community members – showing how the “function of a hospital”, as well as its art, has evolved.

We don’t often recognise the impact of our surroundings until we are forced to reckon with a space – like, for example, in the emotional and physical confines of a hospital room. Hospital environments are an integral part of healing; whether they provide comfort, cure or anodyne efficiency is up to those who create them. And one particularly powerful choice is to place popular art in a public-health space.

We see this with the well-known Mexican painter Diego Rivera, who was commissioned to create a mural for the Centro Médico Nacional La Raza in Mexico City.

Centred around a depiction of the Mesoamerican goddess Tlazoltéotl giving birth and flanked by two trees, the composition is a riot of activity, depicting people with illnesses, surgical operations, scans, and consultations with doctors and practitioners. Rivera combined cultural history and modern medicine to illustrate the relevance of health in every individual’s life. His mural provides a vivid reminder to those passing through the hospital of our universal need for healthcare, no matter our stage of life or history.

Today, institutions regularly incorporate art into the work of healing, acknowledging the impact it can have on individuals and spaces. The NHS has developed a substantial art collection since its founding in 1948, and charitable organisations such as Paintings in Hospitals and Art in Healthcare help to distribute artwork throughout the UK.

The increased demand for art responsive to or reflective of healthcare environments has opened new avenues for creativity, and art is now commonly created and installed as a healing tool for patients. These movements – from art commissions to art therapy – have empowered new ways of articulating health, illness, and wellness from increasingly varied perspectives. As an adult, I found creating art helpful during another bout of illness; when controlling my surroundings and my physical experience wasn’t possible, it mattered to have a method of channelling pain into promise.

Recent research has also provided a stronger understanding of how art impacts our health. Engagement with art has been shown in various studies to reduce pain-medication use, length of hospital stays, anxiety, physical and psychological symptoms.

Our use of art in healing settings reflects our sociocultural priorities, including the more humanistic and patient-centric approach of today’s hospitals and healthcare practices. The future may hold any number of artistic approaches to hospital spaces, reflecting our continued discoveries about the impact of art on wellbeing – from affecting one individual’s hospital experience to building towards greater collective health.

About the author

Anne Wallentine

Anne Wallentine is a writer and art historian with a focus on the intersections of art, culture and health. A graduate of the Courtauld Institute of Art, she writes for outlets that include the Financial Times, the Economist, Smithsonian Magazine, the Art Newspaper and Hyperallergic.