Historically, people with albinism were often objectified as curiosities to be gawped at. Today, it’s still common to be singled out or cruelly joked about, and Caroline Butterwick has been made to feel self-conscious about her own albinism. Here she uses archival objects and images to tell the personal story of how the genetic condition has affected her life, and how self-acceptance has followed understanding.

A personal history of albinism

Words by Caroline Butterwick

- In pictures

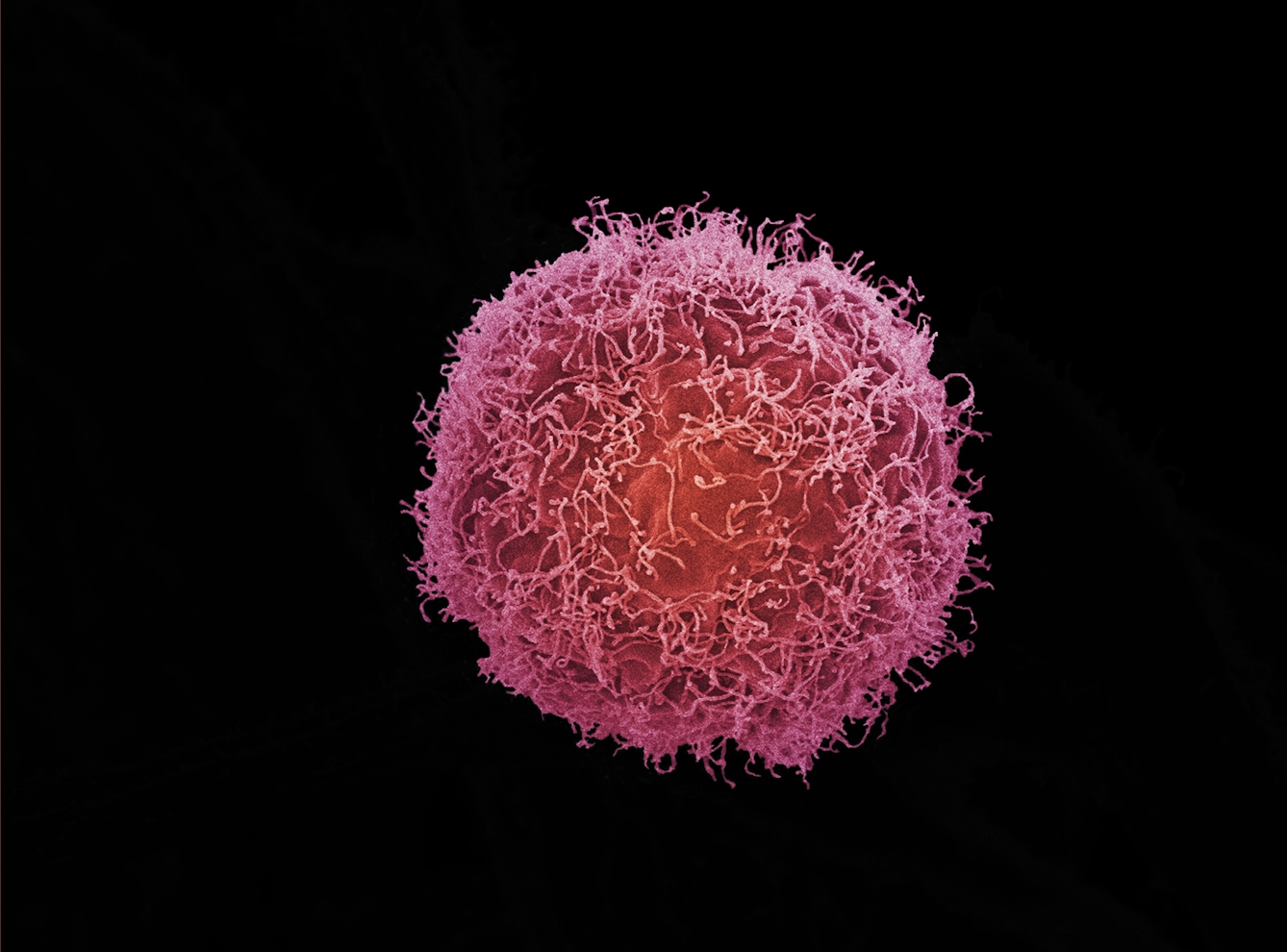

Despite it being a genetic condition present from birth, I didn’t realise I had albinism until my teens. It was a word I’d heard spoken about me as I sat in the ophthalmologist’s chair as a child, lights shone in my eyes to examine them, but it wasn’t until I googled the word that I realised what it meant. Albinism affects the production of melanin, which is the pigment in the eyes, skin and hair. It commonly causes visual impairment, as the development of the retina is affected, with many also experiencing astigmatism (where the eye is shaped like a rugby ball) and nystagmus (involuntary eye movements side to side).

I’ve never had genetic testing to show what kind of albinism I have, but it’s down in my notes as “ocular albinism”, meaning it’s predominantly my eyes that are affected. Albinism causes photophobia, meaning the eyes are sensitive to light. When the sun is in my eyes, everything is whitewashed, like an overexposed photo, and it hurts. You may associate sunglasses with visual impairment, as many blind and partially sighted people – myself included – find they help protect our eyes. There’s always a pair of sunglasses in my bag.

Growing up with an impairment is a process of simultaneously learning about the specifics of your condition, and about how it relates to your life and your place in the world. It took me a while to realise I was different from my peers, despite always being partially sighted. As a teenager, I tentatively tried to embrace things that would help me, like a talking watch – which was thankfully sleeker and more subtle looking than this watch for blind people from 1929. Still, there were awkward moments when I’d accidently press the watch and it would shout “ten fifty-five a m” in the middle of class.

It was around this time that I started taking part in activities run by a local visual impairment charity. There is a tension between disability and charity – finding the services useful, while feeling awkward about being a recipient of charity, along with some of the problems about how charities ‘use’ disabled people to provoke pity. Still, aged 14, I went on a week-long trip to the Lake District with a group of other visually impaired (VI) young people, and it was good to talk to others who understood the challenges of being VI. It helped with my acceptance of myself as a disabled person.

Visually impaired people have often been marginalised in society. Victorian “blind asylums”, like the one pictured, segregated blind people. While society has moved on, visually impaired people are often treated differently. At school, I had a growing awareness that there was something unusual about me. My peers didn’t need someone to take notes from the whiteboard, or for the blinds to be closed so the light didn’t hurt their eyes. When I’ve had office jobs, I’ve been very conscious of how I have the computer screen magnified, and how I struggle to recognise colleagues. My confidence has grown along with my self-understanding, but I’m still often made to feel different.

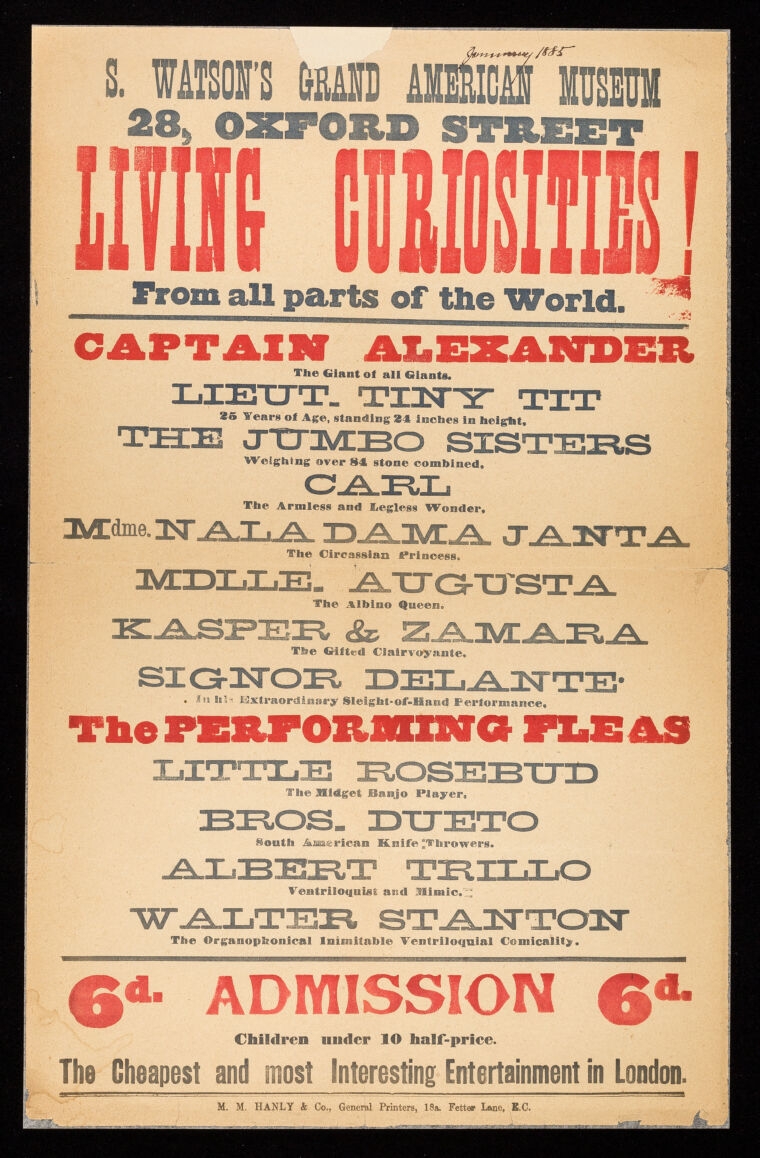

People with albinism have long been stigmatised. This Victorian poster advertising a museum of “living curiosities” includes Mademoiselle Augusta, “the albino queen”, as if she is someone to gawp at rather than a real person. Misconceptions and prejudices about albinism persist today. I’ve heard people make cruel comments or jokes about ‘albinos’ that make me feel like I’m different and something to be laughed at. Although I’m officially diagnosed with ocular albinism, I also have very pale skin and as a child my hair was almost white. Some people can tell I have albinism just by looking at me, whereas others are surprised.

Many people with albinism are at increased risk of skin cancer because of the lack of melanin in our skin. My skin is very sensitive and burns easily, which means I must be careful in the sun. My mum would slather me in sunscreen as a child, and I am always careful to do the same now, or to wear clothes that cover my skin. When I was growing up, classmates would comment on how ‘pale’ I was, which made me feel like I was unusual – I remember one girl regularly telling me I should use fake tan.

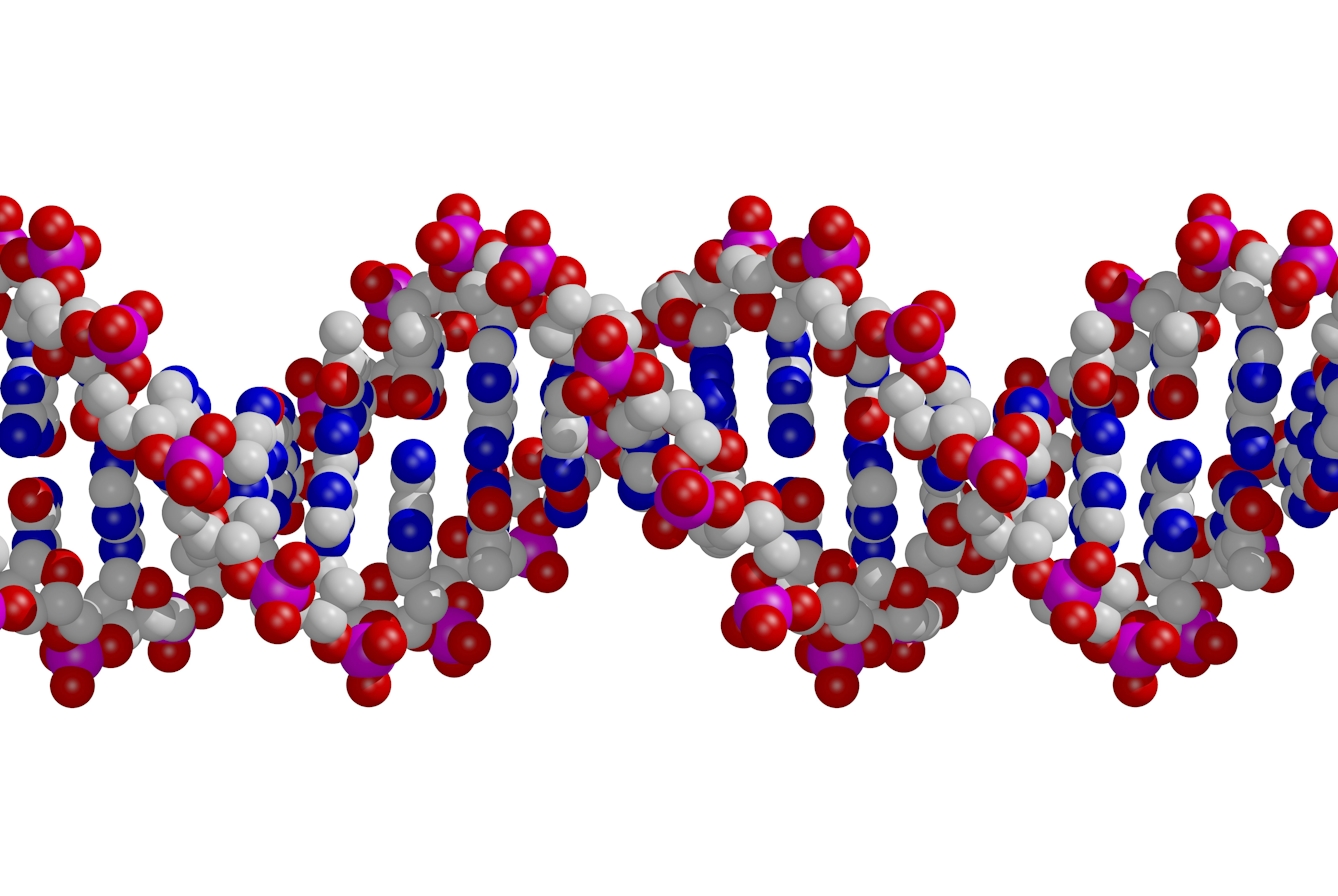

I have a better grasp of what albinism is now and how it impacts my life, but one thing that’s missing is a clear definition of the kind of albinism I have. In an online group I’m a member of, I’ve seen others comment that they were diagnosed with ocular albinism as children, but genetic testing showed they have oculocutaneous albinism, the most common type, affecting the skin, hair and eyes. At some point, I’m going to ask for a referral for genetic testing. While it’s not essential, it feels like the next step in understanding – and embracing – myself as a person with albinism.

About the author

Caroline Butterwick

Caroline Butterwick is a writer, researcher and freelance journalist based in North Staffordshire. She’s currently working on a nonfiction book proposal, and her freelance journalism has featured in a range of publications, including the Guardian, the i paper, Mslexia, and Psychologies. She is studying for a PhD in Creative Writing that explores the power of memoir as a counternarrative to dominant models of disability, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council/Midlands4Cities.