Many artists in the 1980s and 1990s turned their art into activism to raise awareness of the emerging AIDS epidemic. These public health posters from around the world show how they creatively challenged a growing environment of fear and ignorance.

Artists, activism and AIDS

Words by Lalita Kaplish

- In pictures

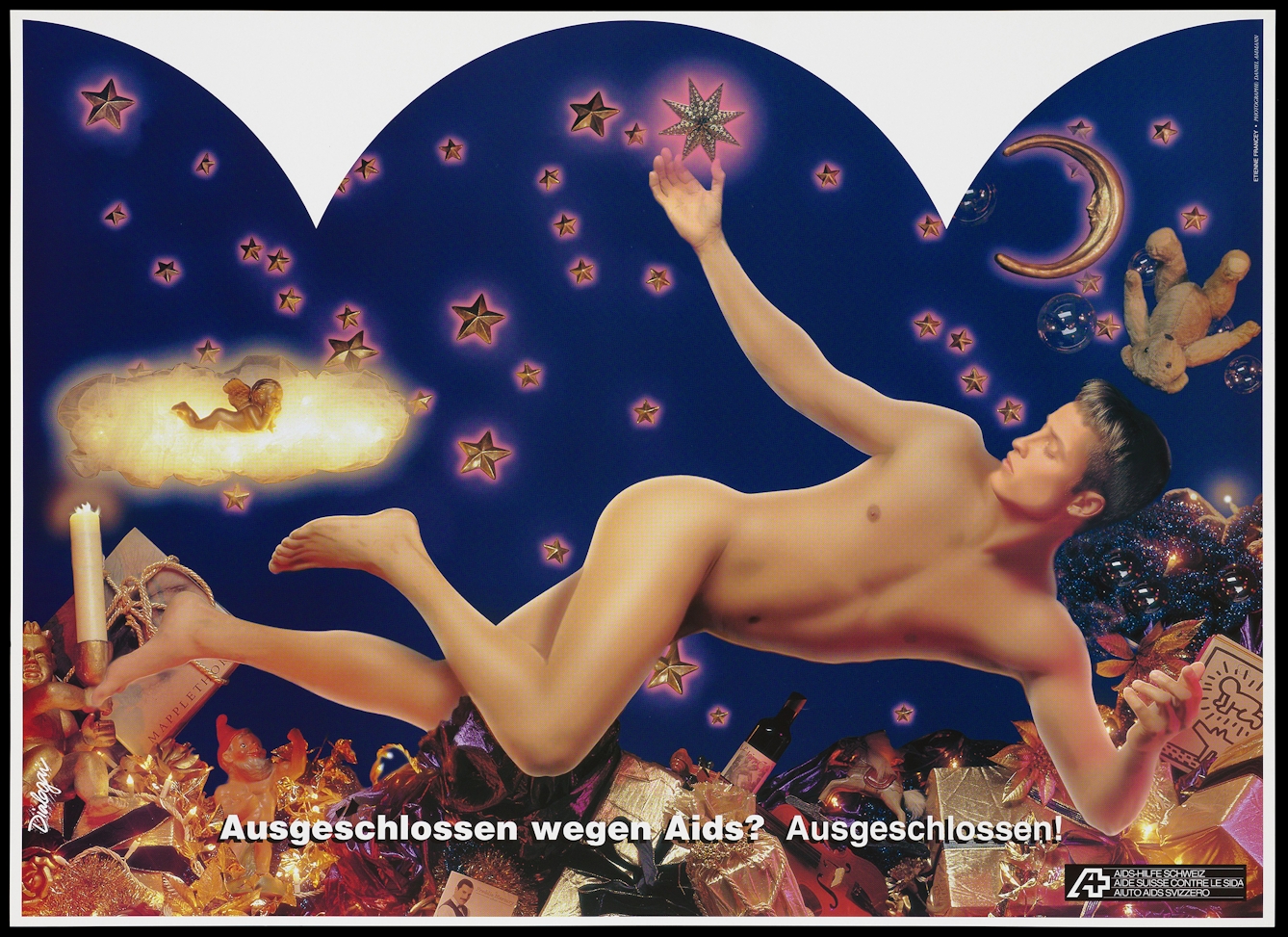

The translation of the caption on this poster from the Swiss AIDS Foundation is “Excluded because of AIDS? Excluded!”. By the 1990s it was becoming clear that everyone was vulnerable to the HIV virus, but this poster is a reminder of the prejudice and suspicion that people with AIDS and HIV experienced during the epidemic. Just behind the model’s left hand are graphics of a baby and dog, referencing artist Keith Haring. Immediately below the model’s lowered knee is a photograph of singer Freddie Mercury, and behind the extended foot is a book bound in rope with the name of photographer Robert Mapplethorpe. All these artists died from AIDS; they were also gay. The objects are embedded in a firmament of stars, gifts, wine and glitter – underlining the irony that they were celebrated and admired for their talents yet excluded for their illness and their sexuality. For many successful artists, such as Derek Jarman, just making their HIV-positive diagnosis public was a form of activism because of the bigotry and ignorance associated with AIDS. That so many not only chose to do so but also actively campaigned for others is remarkable.

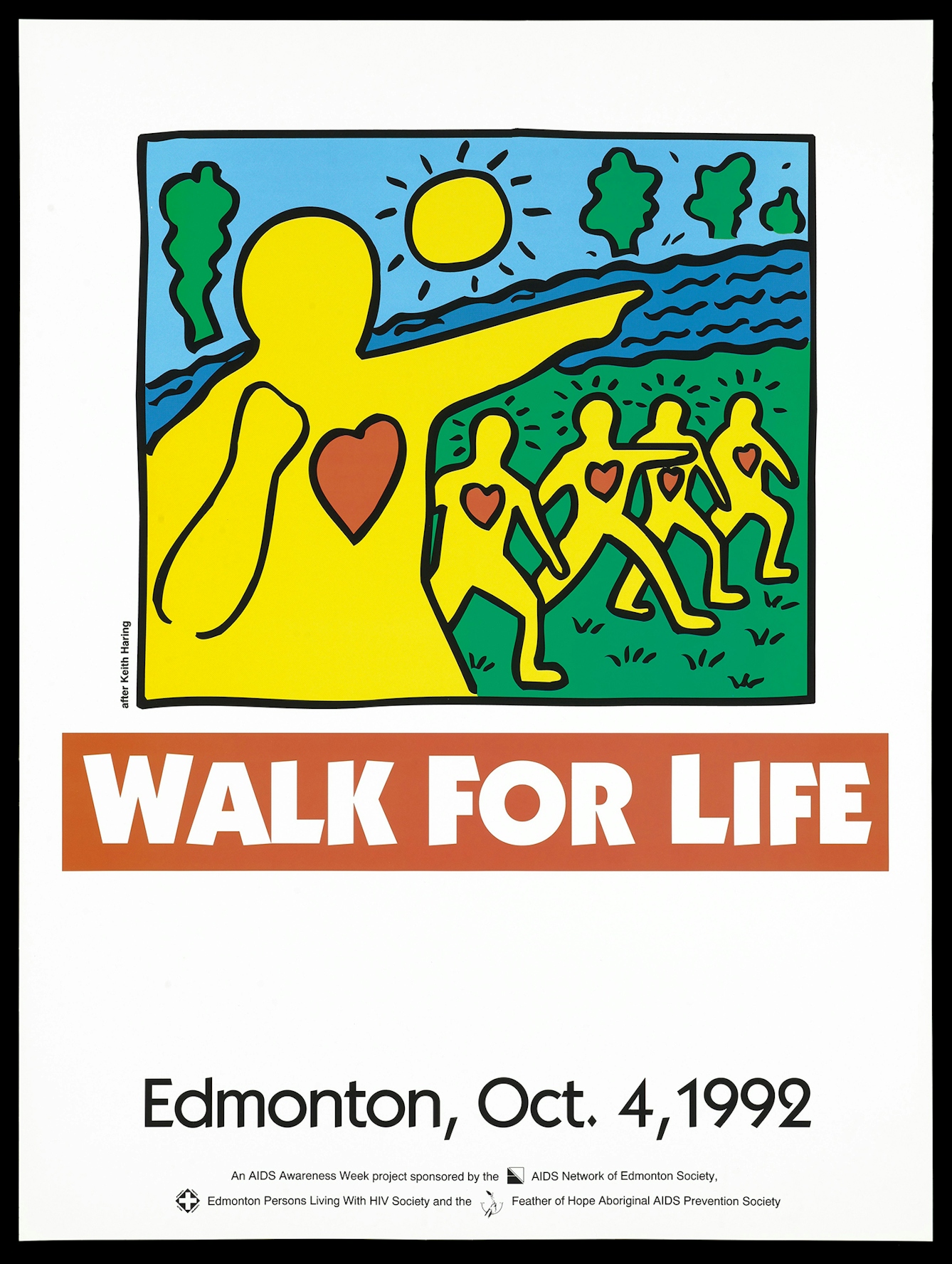

LGBTQ+ communities were the hardest hit by the epidemic, but they were also among the first to raise awareness and actively campaign for safer health and sexual practices. Among the early campaigners were many artists and performers who contributed their skills, as well as their time and effort, to the fight. Keith Haring was diagnosed as HIV-positive in 1988, but he was open about his diagnosis, and throughout his illness used his success and art to raise awareness of the epidemic and homophobia. In 1989 he established the Keith Haring Foundation to provide funding and imagery for AIDS organisations and children’s programmes at a time when many (including the media) saw the distinction between healthy and sick as virtually synonymous with straight and gay. This Canadian poster describes the artwork as “After Keith Haring” in acknowledgement of his contribution.

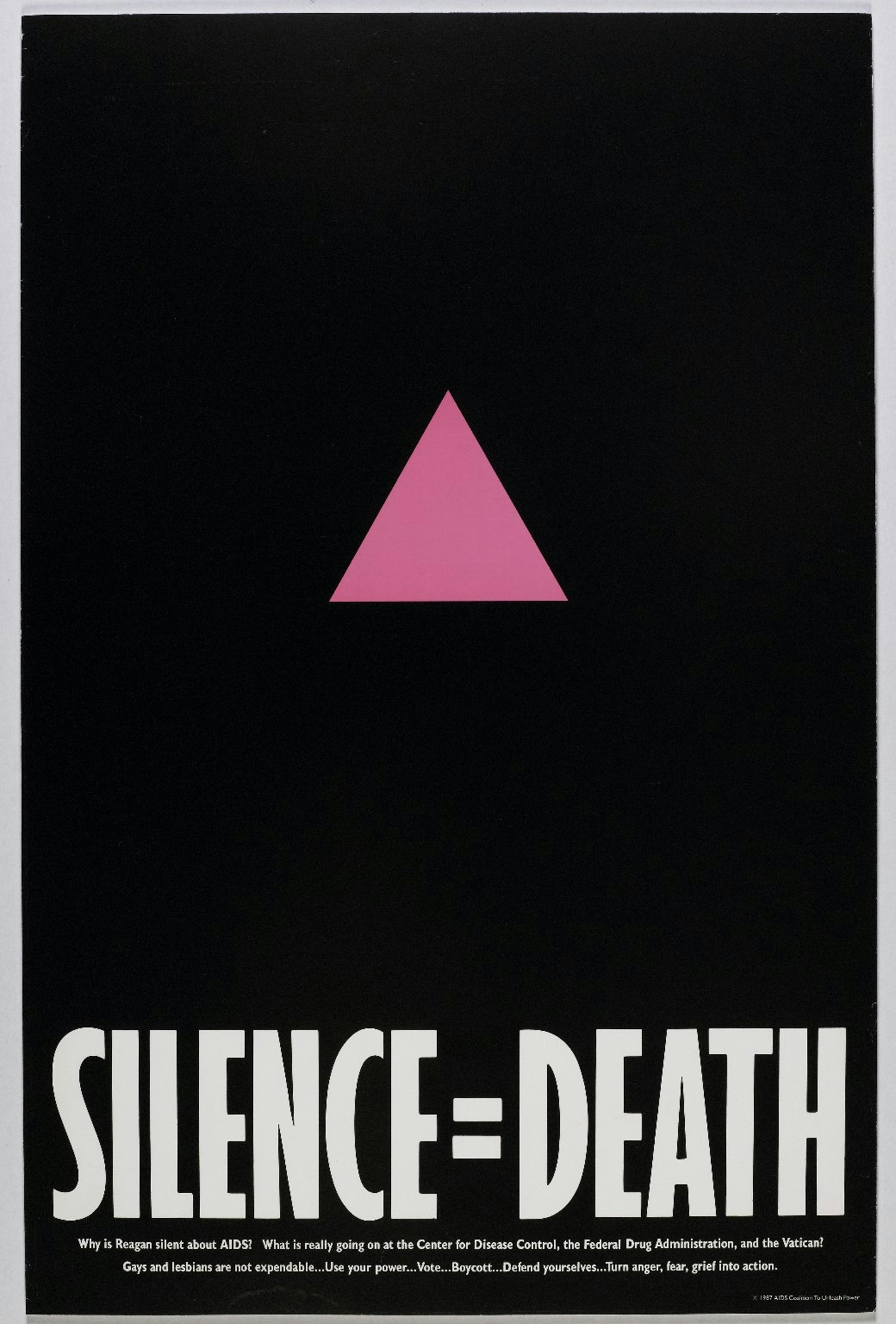

In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, LGBTQ+ communities in the United States were often excluded from political power and hence from health and social care and medical research. This poster, created by the New York City collective Silence=Death Project, was a call to action, reminding local LGBTQ+ communities that the consequences of staying quiet and doing nothing might be death. Avram Finkelstein, a founding member of the collective, likened the group to feminist collectives such as the Guerilla Girls, who were as much about consciousness-raising within their community as about agitating for change. The pink triangle, used to identify gay people by the Nazis, was a powerful signifier of the consequences of exclusion, but its horrific origins are subverted by its (accidental) inversion. And the call to action is reinforced by the wording at the bottom of the poster: “Turn anger, fear, grief into action.” The poster was adopted by perhaps the most prominent LGBTQ+ campaign groups of the time, ACT UP, and became a symbol of the fight against the epidemic.

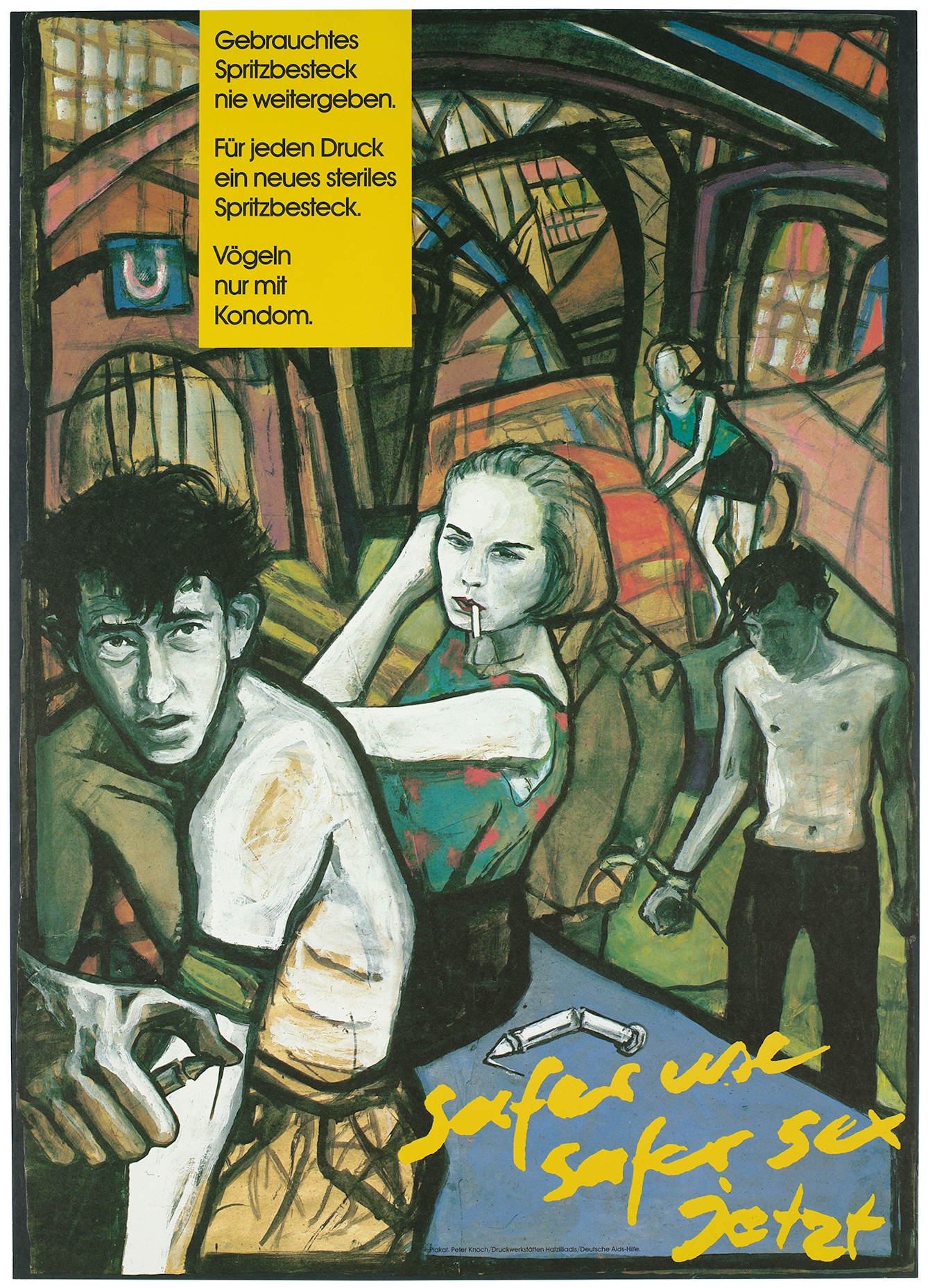

This poster from the German AIDS organisation Deutshe AIDS Hilfe is aimed at young habitual drug users. The text uses language that they would recognise: “Never pass on used syringes. A new sterile syringe set for each print. Birds [women] only with a condom. Safer use, safer sex, now.” The artwork is by artist Peter Knoch, an art student in Berlin in the 1980s and 1990s. During the 1990s Knoch participated in a number of exhibitions related to AIDS awareness and fundraising. As a young gay man in Berlin, he would have been only too aware of the impact of the AIDS epidemic. Knoch continued to challenge the status quo in his career. He co-founded the ‘Freie Klasse’ at the Berlin Art Academy – notable for its rejection of a head professor in favour of a constantly changing programme of lecturers, and he continues to work as a successful artist.

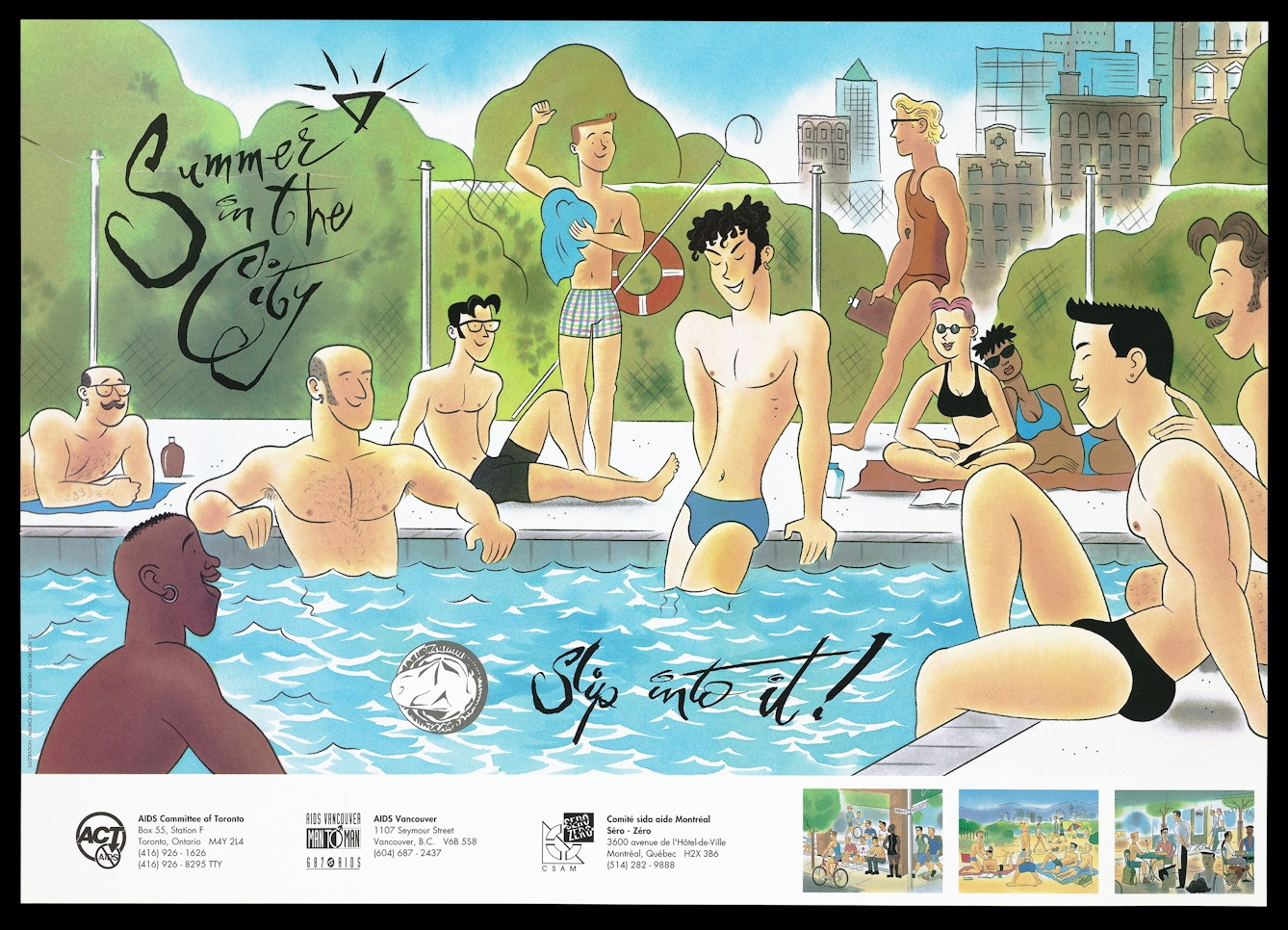

Canadian artist, cartoonist and zinemaker Maurice Vellekoop depicts gay life in his work, often with a humorous or mildly satirical edge. This poster for the AIDS organisations in Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal is very different in tone from most AIDS health information of the 1980s and 1990s. A cosmopolitan group of LGBTQ+ people relax around an urban pool, celebrating ‘Summer in the City’, while an image of a folded condom with the words “Slip into it” reminds the viewer to practice safe sex. Vellekoop already had an established audience for his work and his recognisable style would likely have been familiar to them. The poster is a friendly reminder from one of their own to take precautions but not give in to fear and bigotry.

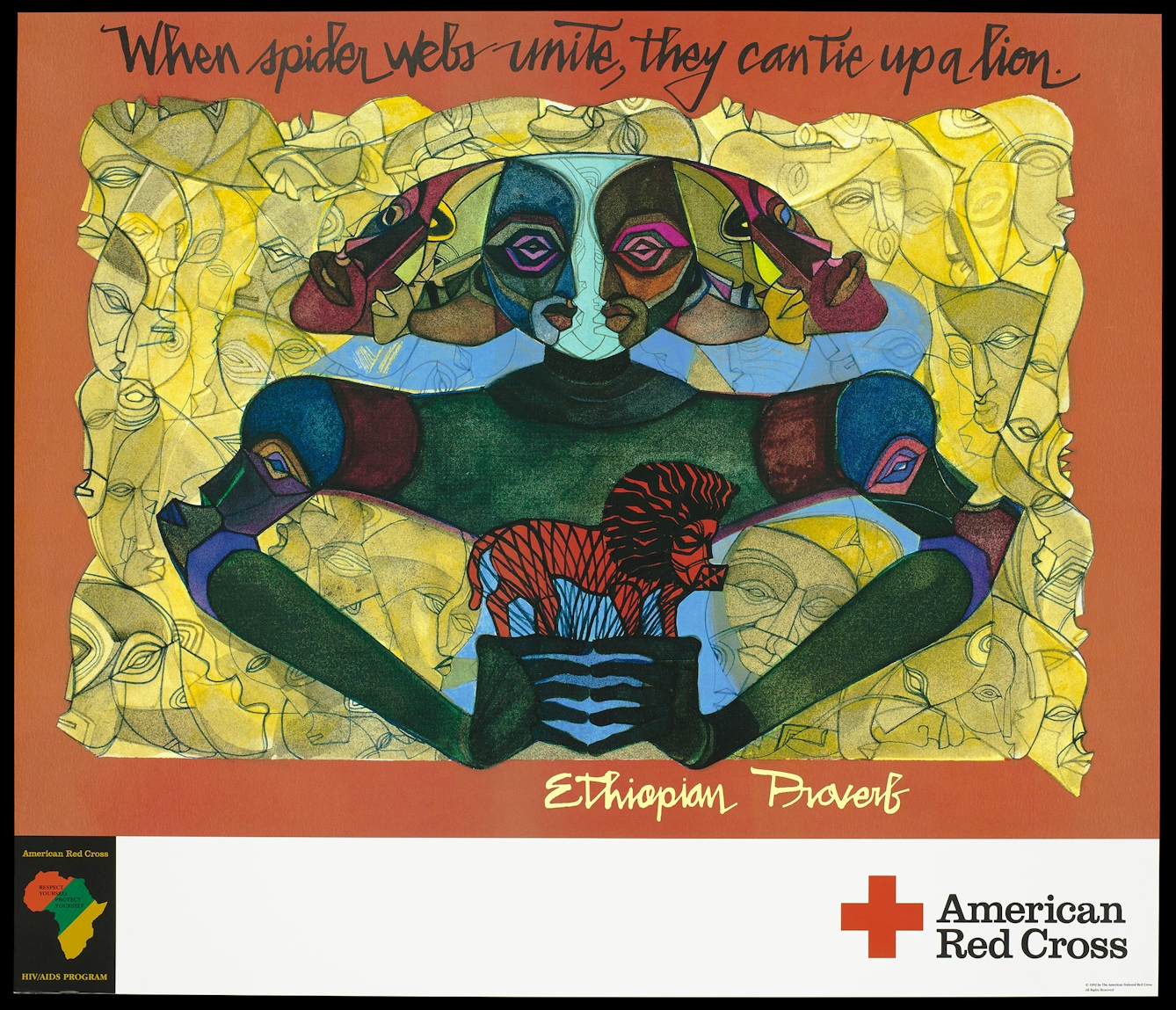

The work of African American artist Damballah Dolphus Smith has been exhibited in numerous solo and group shows in the United States. Smith’s art is informed by his African roots, and African imagery often featured in his work. He said that he wanted his art to “transport the viewer back to gather sensory awareness of the rich and great culture of my people”. In 1992, Smith designed six posters, including this one, for the American Red Cross HIV/AIDS Program in Africa. Each poster includes a proverb from a different African country. Damballah Dolphus Smith died from complications due to AIDS that same year. Clearly this work was important to him and shows how much he cherished and supported his culture and community.

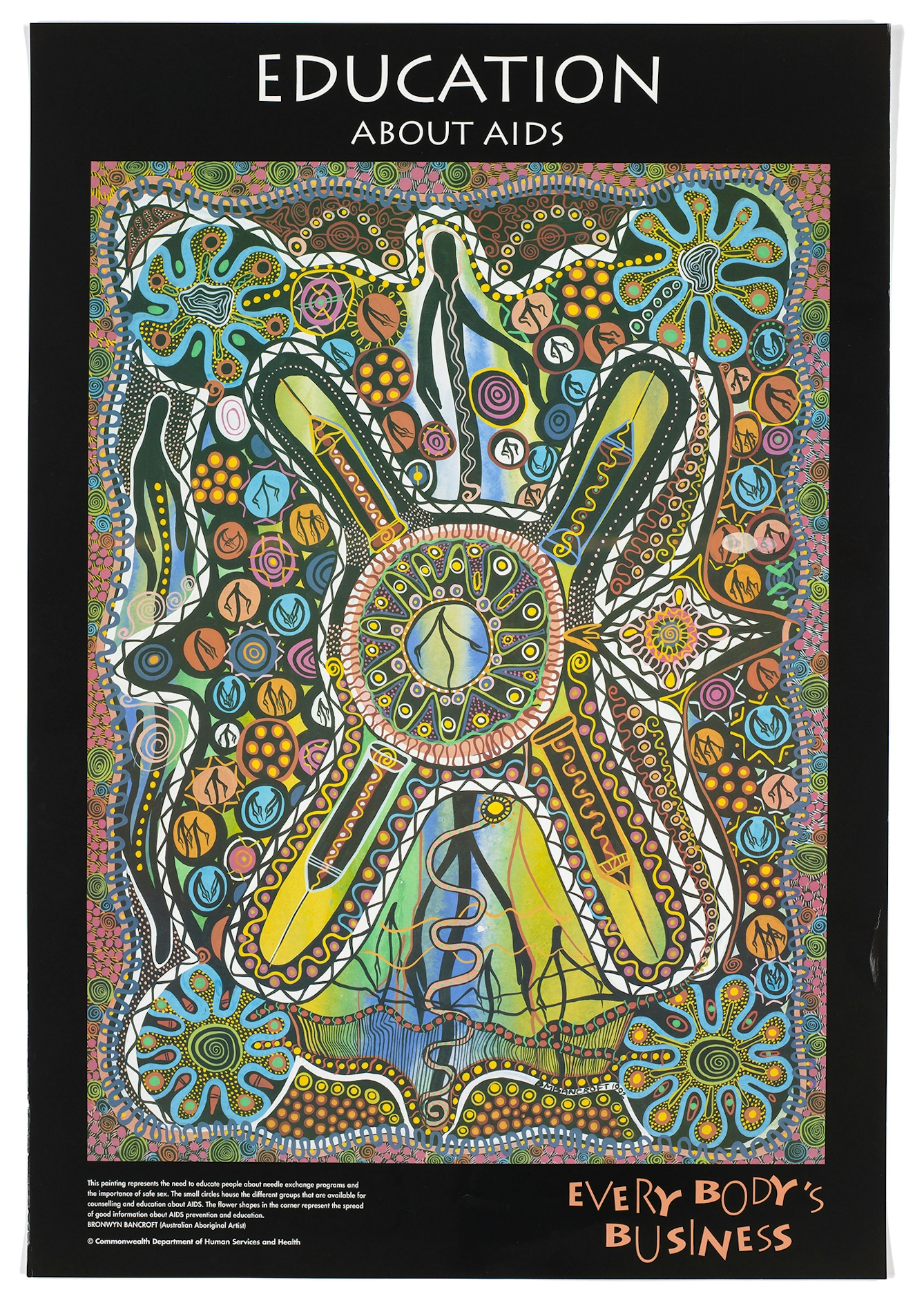

Like Smith, many artists who contributed to AIDS campaigns were already activists in their own communities. Bronwyn Bancroft, a proud Bundjalung woman, is an established Australian artist whose work has been acquired by major Australian galleries and private collections. She is a founding member of Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative (established in 1987), helping to support hundreds of Aboriginal artists in New South Wales. This poster by her is about the importance of education in fighting the AIDS epidemic. She says, “This painting represents the need to educate people about needle-exchange programmes and the importance of safe sex. The small circles house the different groups that are available for counselling and education about AIDS. The flower shapes in the corner represent the spread of good information about AIDS prevention and education.”

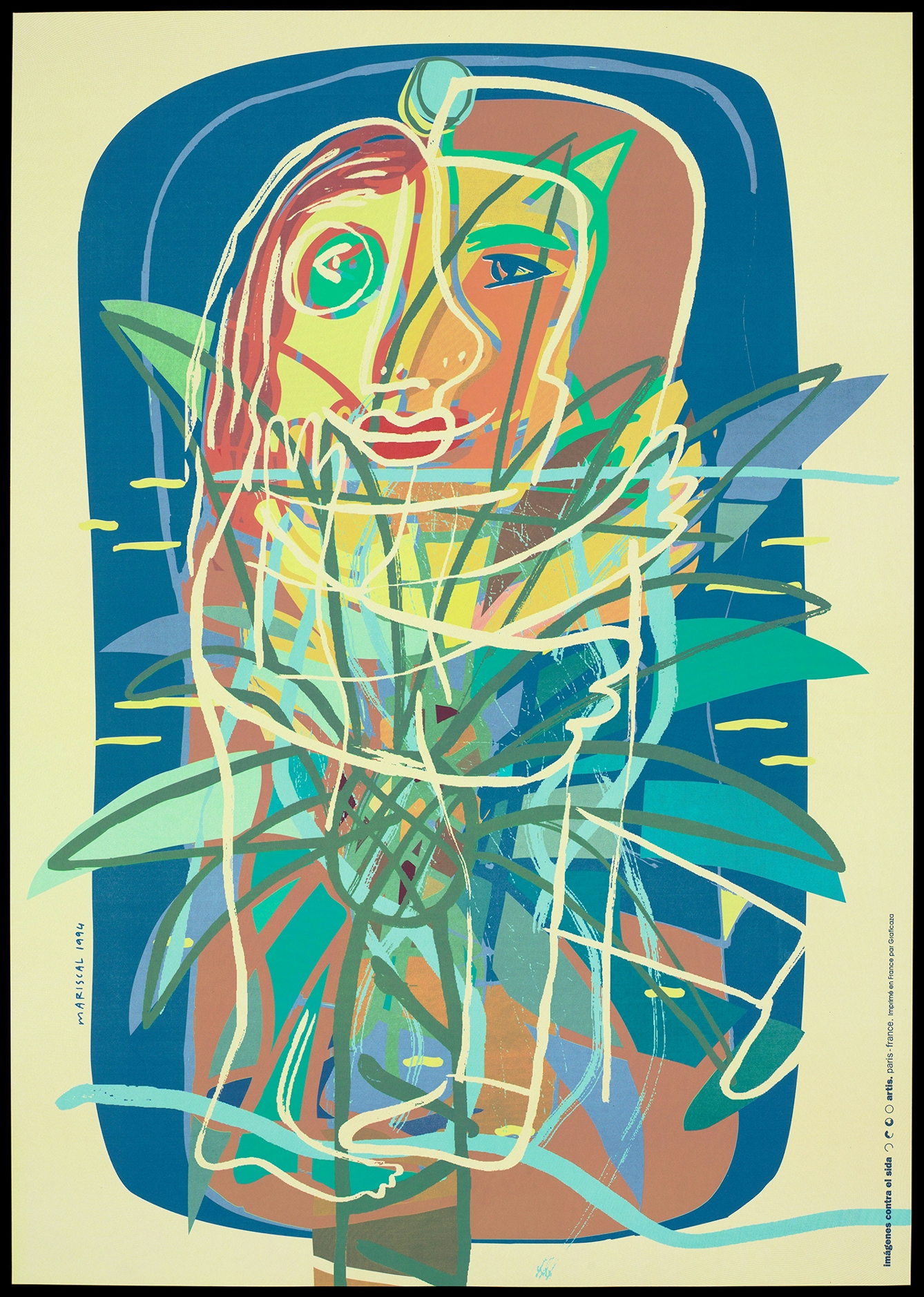

Many art-led initiatives were used to raise awareness and funds during the epidemic. This poster is from a series titled ‘Imàgenes Contra EL SIDA’ (Images Against AIDS), published in 1994 by Artis in France. The palm tree in this poster by artist/activist Javier Mariscal is traditionally associated with freedom, righteousness, bounty, resurrection and victory, and could therefore be interpreted as the rights of those with AIDS. Mariscal is a painter, sculptor, graphic designer, industrial designer and comic artist who works closely with his local community in Valencia, Spain. In 2001, he designed the diary-room chair used in the reality-TV programme ‘Big Brother’.

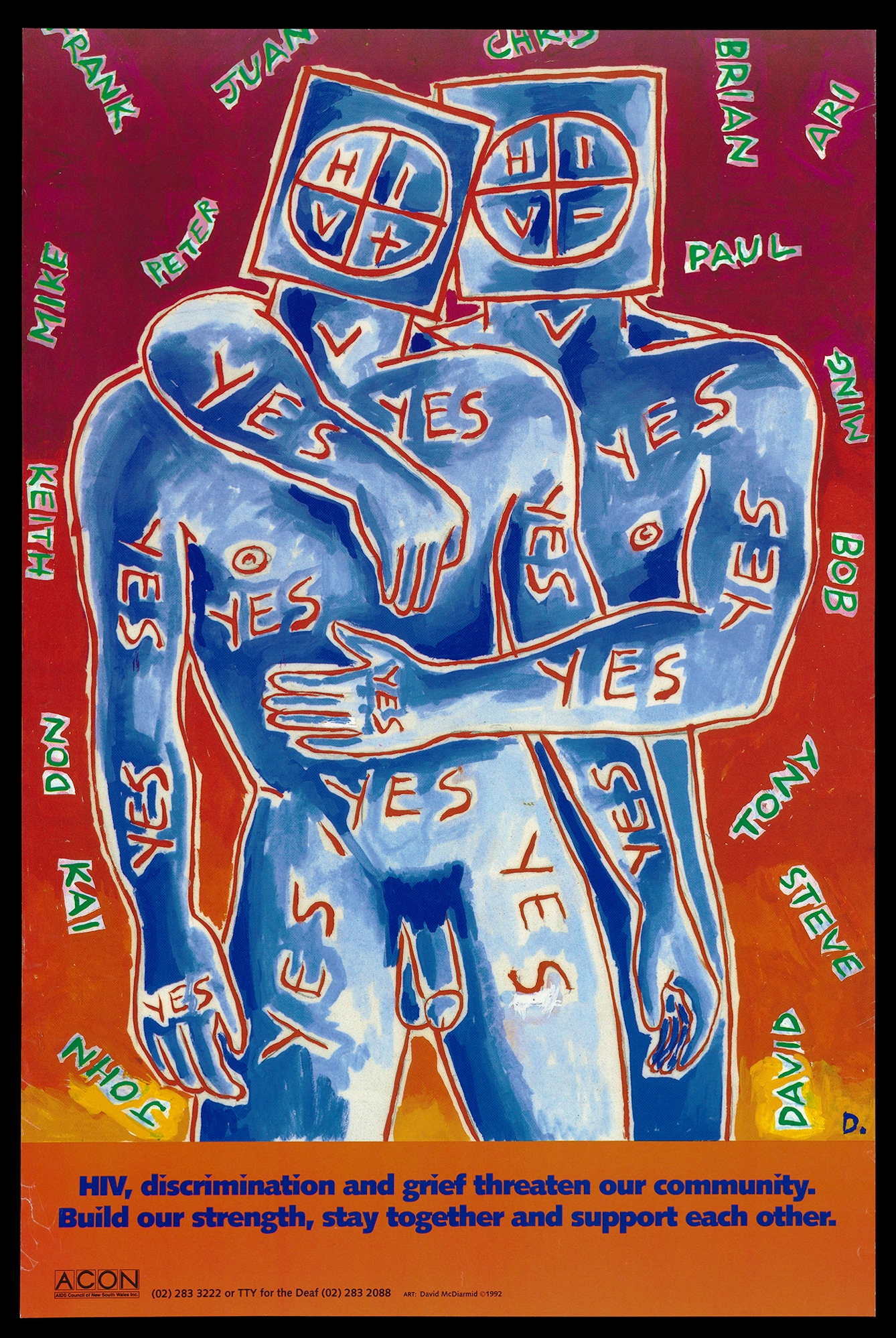

Australian artist David McDiarmid was involved in gay rights from the early 1970s. He was working in New York in 1986 when he was diagnosed HIV-positive. He returned to Australia, where he devoted himself to activism and producing art that raised awareness of the AIDS epidemic. McDiarmid was variously artist/designer and artistic director for the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras. Among his artistic contributions was a large-scale sculpture based on the Mexican Day of the Dead, which he designed with members of the HIV Living Group for the 1992 Mardi Gras. This poster, created in 1992 as one of a set of six for the AIDS Council of New South Wales, addresses the gay community with a plea to take care of each other. David McDiarmid died of AIDS-related conditions on 25 May 1995.

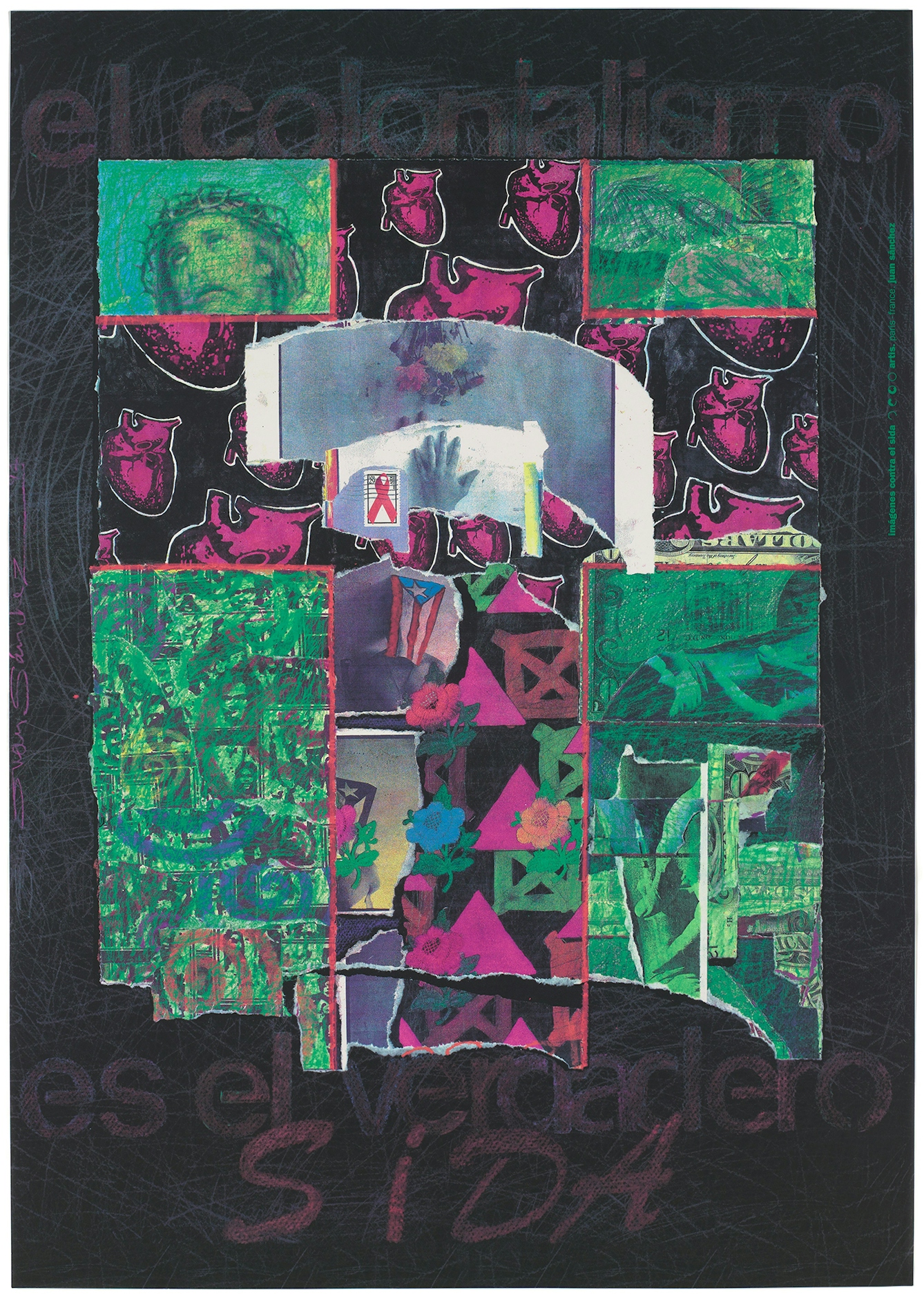

Juan Sánchez is one of a generation of artists who, in the 1980s to 1990s, explored questions of ethnic, racial and national identity in their work. Sánchez was known for his brightly coloured, mixed-media canvases that addressed issues of Puerto Rican life in the USA and in Puerto Rico. In this poster, which says “Colonialism is the real AIDS”, there are images of pink hearts and pink triangles, along with the red ribbon used by AIDS campaigners, collaged with imagery relating to religion, Puerto Rico and the United States. The poster addresses the wider inequalities of the epidemic.

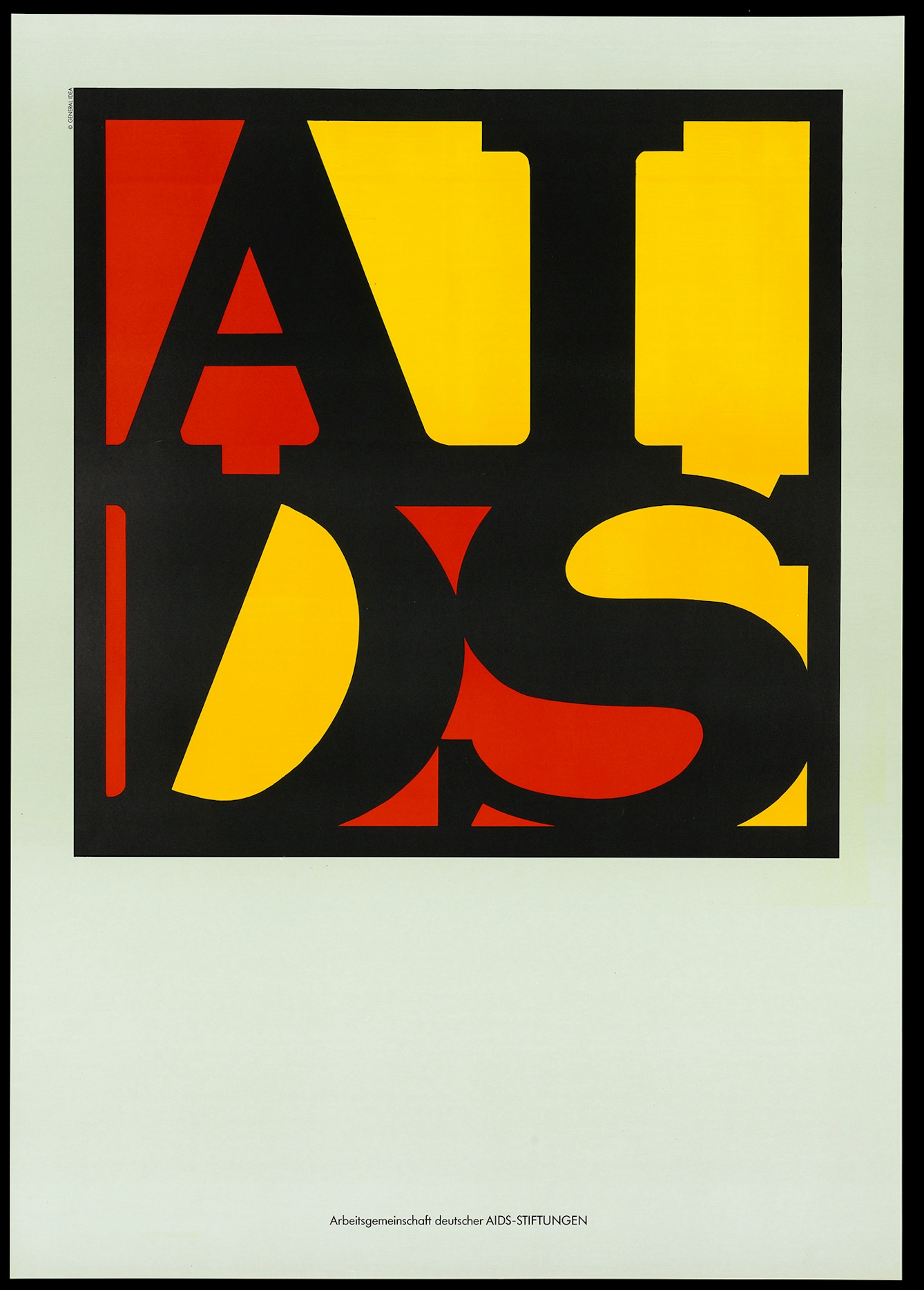

‘General Idea’ was an art collective of three Canadian artists: Felix Partz, Jorge Zontal and A A Bronson, working between Toronto and New York City. Their first AIDS-related work was created for a 1987 exhibition in support of the American Foundation for AIDS Research (amfAR). The painting substituted the word AIDS in the same layout and colours as the motif LOVE, as used in multiple works from the 1960s by Robert Indiana.

The logo was then used in a poster campaign called ‘IMAGEVIRUS’ across New York and San Francisco. As Bronson explained, the logo was meant to go viral: “It would spread within the culture and create a… visibility for the word ‘AIDS’, so it couldn’t be swept under the carpet, which was… what was happening.” The image did indeed proliferate in a variety of formats and was used by medical and charitable organisations. This version, produced for the Working Group of German AIDS Foundations, replaces the red, blue and green of the original for the colours of the German flag.

The group’s activity ended in 1994 with the deaths of Zontal and Partz from AIDS-related causes. Weeks before their deaths they incorporated powerful photographs of themselves in works that made the epidemic all too human.

About the author

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the history of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.