Protestors railing against “government lies” at weekend anti-lockdown protests have become commonplace in the last year. But such sentiments are old news – they have their counterparts in the defiance of anti-cholera supporters 190 years ago.

In May 2020, at an anti-lockdown protest in London, there were signs saying, “Fake pandemic” and “I do not consent”. And in the United States, Trump repeatedly downplayed Covid-19, comparing it to seasonal flu and claiming it would just go away, even as cases rose sharply across the country.

Such pandemic denial is nothing new. In 1831 Britain suffered its first ever cholera outbreak. It started in Sunderland, but when central government imposed a lockdown, it met with local resistance.

I feel quite satisfied the reports and statements of this fatal malady have been grossly exaggerated.

Asiatic or Indian cholera, as it was then called, had already swept through Asia and Europe, travelling along trade routes until it took hold in the busy ports of Hamburg and Riga. To stop it reaching Britain, the government ordered any ships returning home to quarantine in port for 15 days.

Despite these measures, in October 1831 several Sunderland residents fell ill. These were the first confirmed cases, but it’s likely that the disease had already spread much earlier, with one instance of a riverboat pilot named Robert Henry dying on 14 August that year with cholera-like symptoms.

“Cholera had already swept through Asia and Europe. To stop it reaching Britain, the government ordered any ships returning home to quarantine in port for 15 days.”

After this flurry of cases, Sunderland’s Board of Health met on 1 November and unanimously agreed that cholera had spread into the town. The board was headed by Dr William Reid Clanny, a consultant at the local infirmary (who would later become famous for inventing the first miner’s safety lamp). He was joined by James Butler Kell, an army surgeon who was the only person in Sunderland who had actually seen cases of cholera first-hand.

On hearing the news, the government imposed a quarantine on Sunderland’s port, banning all ships from entering or leaving. The town’s economy depended on coal exports so, needless to say, many residents were angry and frustrated.

Doctors and businessmen join forces

A group of local businessmen banded together to form an “anti-cholera party”, spearheaded by the Marquis of Londonderry. The aristocrat – who had a past reputation for ‘whoring’ and drunkenness – owned collieries in the area and was not about to see his profits detrimentally impacted.

The group denied that the disease had taken hold in Sunderland and claimed that people had become infected with the far less deadly “English cholera” – a catch-all term for gastroenteritis and more common bowel complaints.

In a letter to the London Evening Standard, Londonderry wrote: “I feel quite satisfied the reports and statements of this fatal malady have been grossly exaggerated.” However, it's clear from later, private correspondence that Londonderry was well aware that there were cholera cases in the town but chose to deny it.

As part of their campaign, the anti-cholera party produced a series of posters. One insinuated that the town’s doctors were motivated by personal gain: “Any Person supplying the Board of Health with a few Cases of Asiatic Cholera, will receive a liberal and substantial Reward; and should none be obtainable, any number of Cases of British origin, however small, will be thankfully received.”

“As part of their campaign, the anti-cholera party produced a series of posters. One insinuated that the town’s doctors were motivated by personal gain.”

But some local doctors colluded in this campaign of misinformation. Many who had agreed at the 1 November meeting that cholera had infected the town later changed their minds – most likely under pressure. They were, after all, dependent on this band of wealthy merchants and landowners for their income.

Vilifying the experts

Of course at that time there was very little understanding about how diseases like cholera spread. Some doctors were “contagionists”, who believed it spread by person-to-person contact. But many, including Clanny, put it down to “bad air”.

Then – just as today – this uncertainty could be seized upon to further a particular agenda. If cholera was carried through the air, for example, what would be the point in quarantining the town?

As Sunderland’s public health official number one, it was Clanny who came under the most fire from these cholera-deniers. “I have come in for my full share of abuse in the cholera conflict,” he later wrote.

Today, high-profile medical experts have experienced similar attacks. Hashtags like #sackwhitty (in reference to UK Scientific Adviser Chris Whitty) have trended on Twitter, and American infectious disease expert, Anthony Fauci, has been repeatedly attacked by Trump and his pandemic-denying supporters, both on and offline.

“Even the cholera victims themselves came in for criticism. The disease mostly afflicted the town’s poorest residents, who lived in overcrowded, dirty lanes alongside the river.”

While there was no social media in the 19th century, people had other ways of smearing the experts. In December 1831 a ‘Lost’ poster appeared that mocked Clanny, comparing him to a dog “afflicted with Cholera-phobia”, who was last seen with his “tail between his legs”.

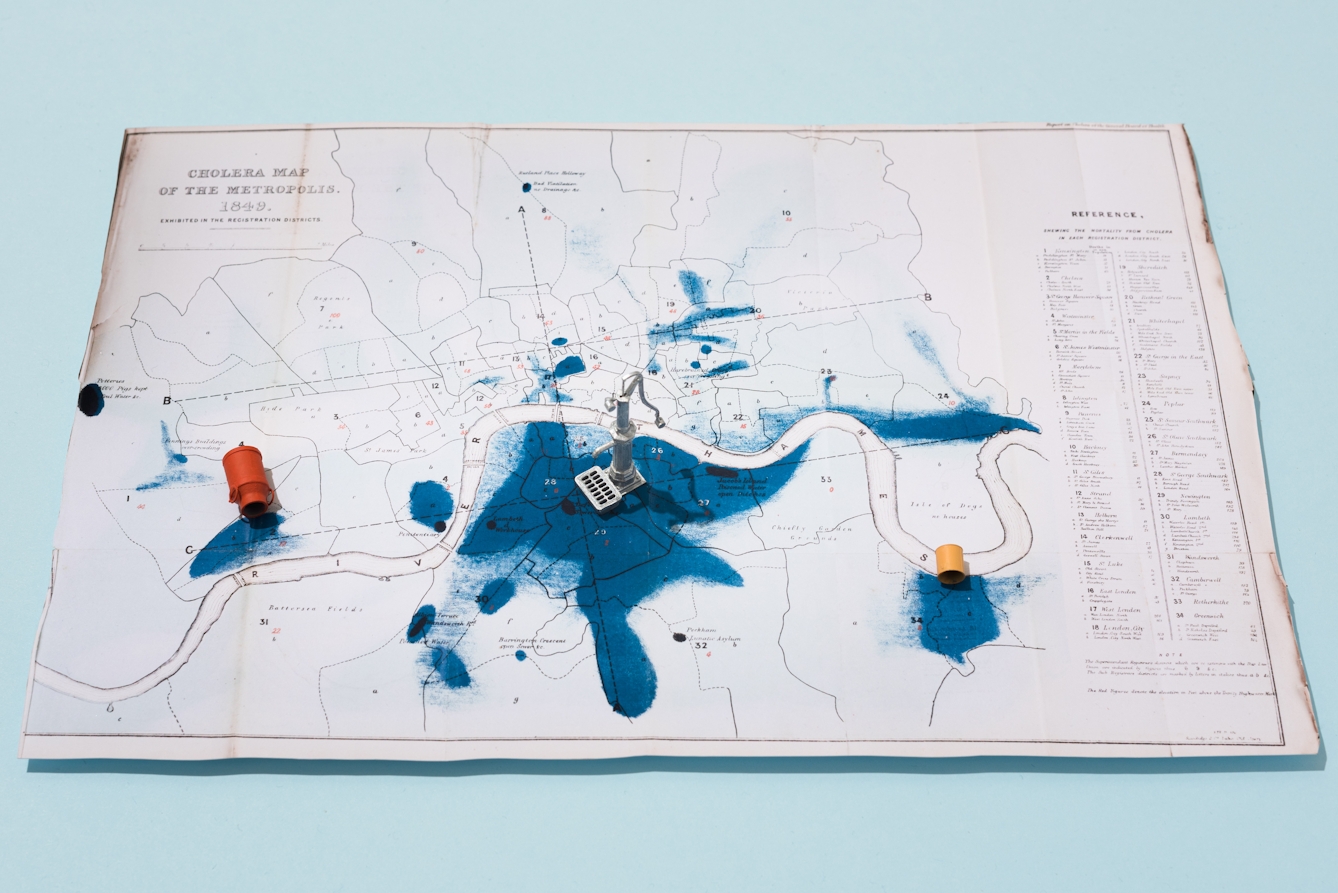

Even the cholera victims themselves came in for criticism. The disease mostly afflicted the town’s poorest residents, who lived in overcrowded, dirty lanes alongside the river. Bad habits and “intemperance” were cited as reasons for the spread. And before the outbreak even reached Britain, one poster cast cholera as a human character who seeks out “the Drunkards, the Gluttons, the Lazy, the Dirty and the Quarrelsome”.

Capitalism versus cholera

After the town failed to contain the disease, it spread across the country, killing around 32,000 people. Sunderland was considered a national disgrace, with the London Medical Gazette writing, “It seems very clear that the public safety is in their estimation a very secondary object when brought into competition with the sale of coals.”

The coronavirus pandemic has raised legitimate questions about how societies balance quality of life and the economy with preventing the spread of a deadly disease. Nonetheless, it’s hard not to view lockdown resistance as history repeating itself.

In ‘Cholera in Sunderland’ (a book published in 1992), co-author Stuart Miller describes how “a remote government in London reacts in panic with ill-considered and half-measured directives” and “the holders of public office act with the basest of motives”.

He ends by saying, “This sort of thing could never happen today.” But, as if getting a brief glimpse into the events of 2020, he tempers it with a final, “Well, probably!”

About the contributors

Rachael Swindale

Rachael Swindale is a freelance writer and TV/ film producer. She writes about film, history, culture and travel for the Guardian and other publications. Her film and TV work includes documentaries for Nat Geo, BBC Storyville and Discovery; and independent shorts selected for the BFI London Film Festival and SXSW. She also writes short fiction and screenplays and is currently working on a TV series set in 18th century London.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.