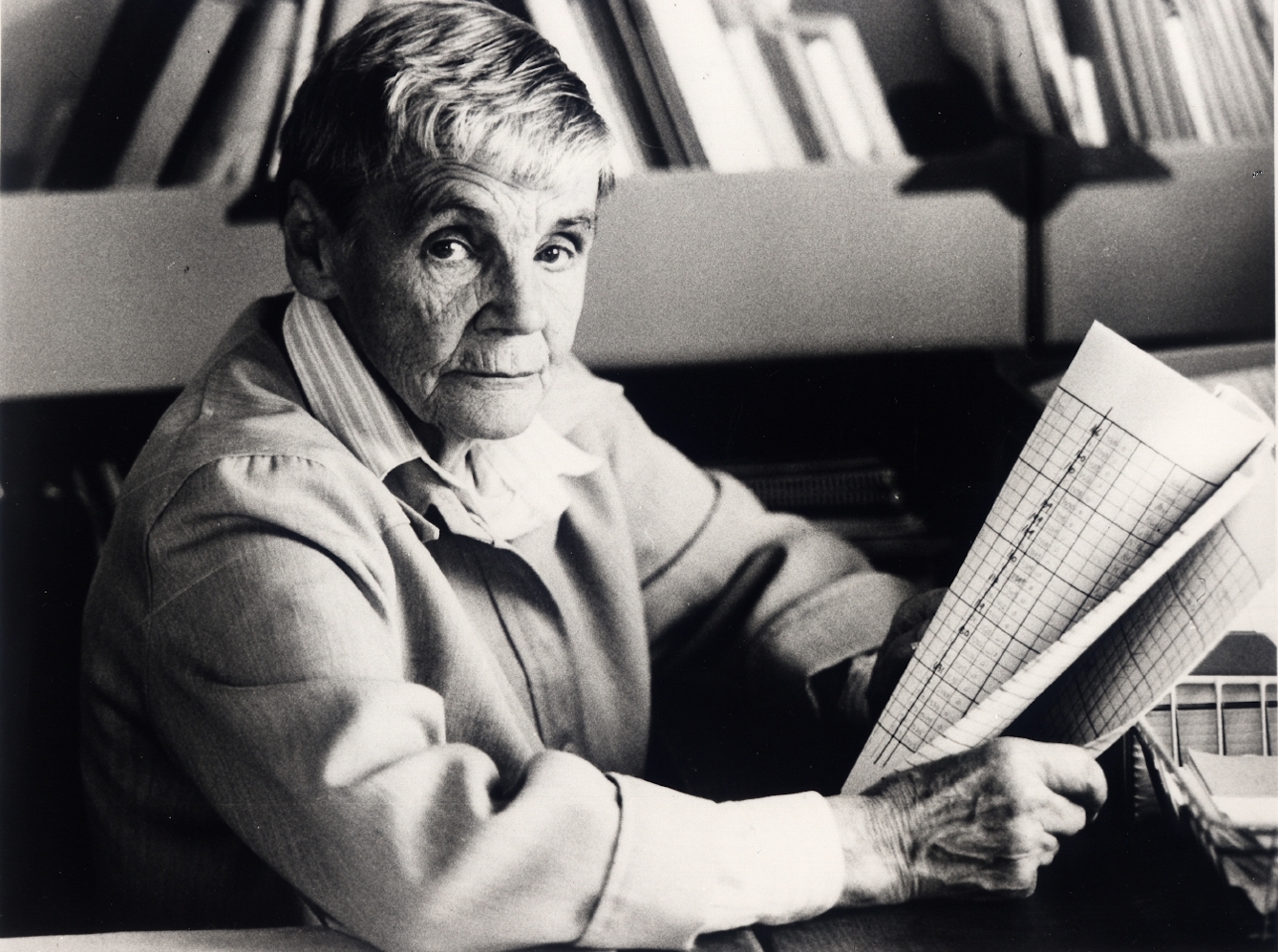

Dr Alice Stewart realised how things in everyday life could be as deadly as any infectious disease. Her pioneering work on the effects of low-level radiation during pregnancy was just one of many achievements in a controversial life dedicated to social medicine.

We are the survivors of slow-motion epidemics

Words by Angela Saward

- In pictures

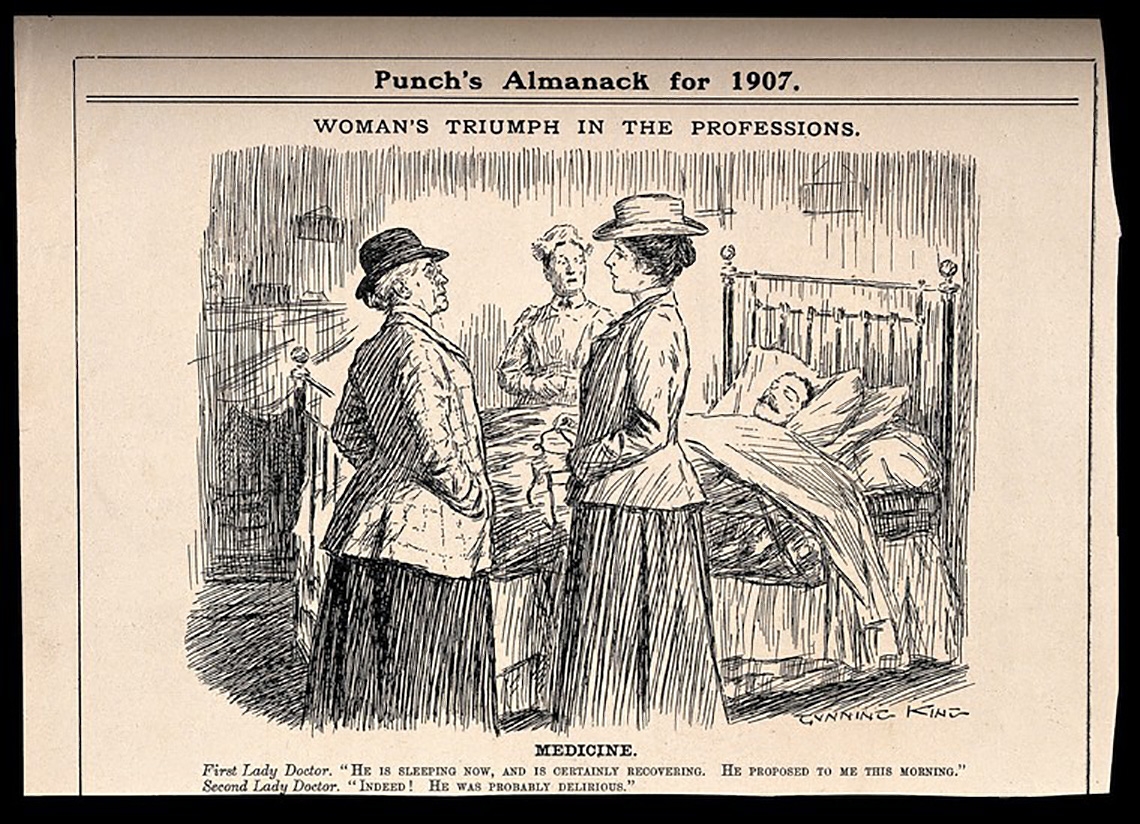

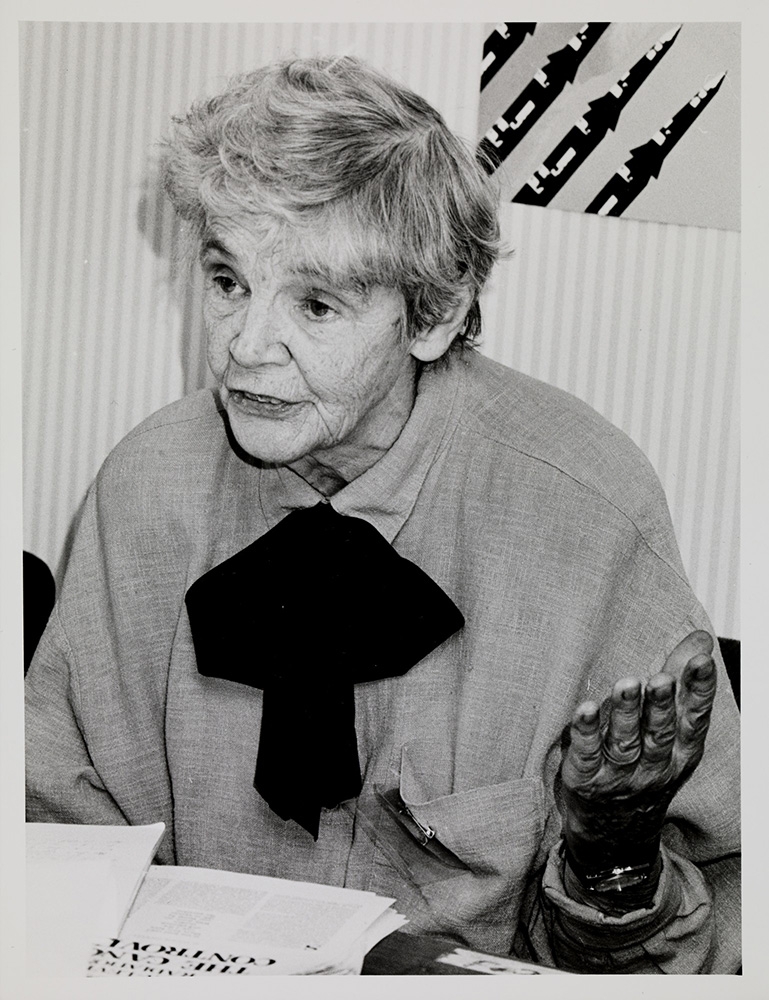

Dr Alice Stewart (1906–2002) was a doctor and epidemiologist, best known for her pioneering work on the effects of low-level radiation on the foetus in the womb. Both her parents had been doctors, and it was from them that she got her sense of social justice. Her mother was among the first female doctors, and her father was an advocate of women in medicine, unlike many of his peers. Alice herself was initially reluctant to follow in their footsteps.

Alice studied natural sciences at Girton College, Cambridge when women were still very much in the minority. In a physiology lecture she was one of only four women along with 200 men, who stamped their feet in unison when the women entered, forcing them to sit together on the front row. Alice went on to complete her medical studies at the Royal Free Hospital in London. She then entered a long and sometimes controversial career in medicine, marrying in her twenties and having two children.

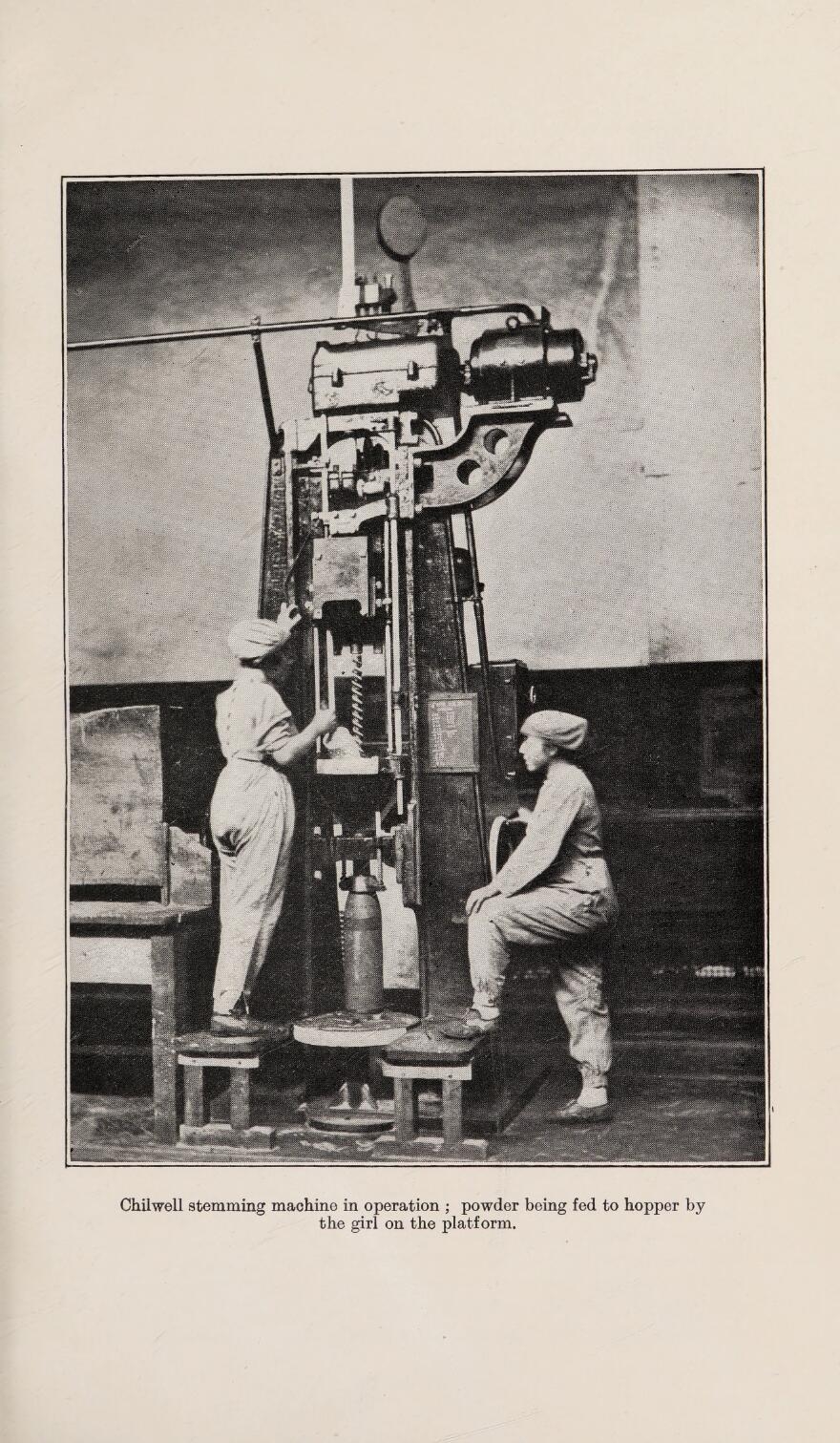

Her career took her to Oxford where, during World War II, she led a survey of munitions workers working with TNT, an explosive. The study was designed to avoid the experience of World War I, when young women working in munitions factories had died of exposure to toxic chemicals. Alice and a team of 44 students spent several months working in the munitions factories, testing their own blood for toxicity. In 1944 her study on TNT factories was published in the first issue of the British Journal of Industrial Medicine, which she co-founded.

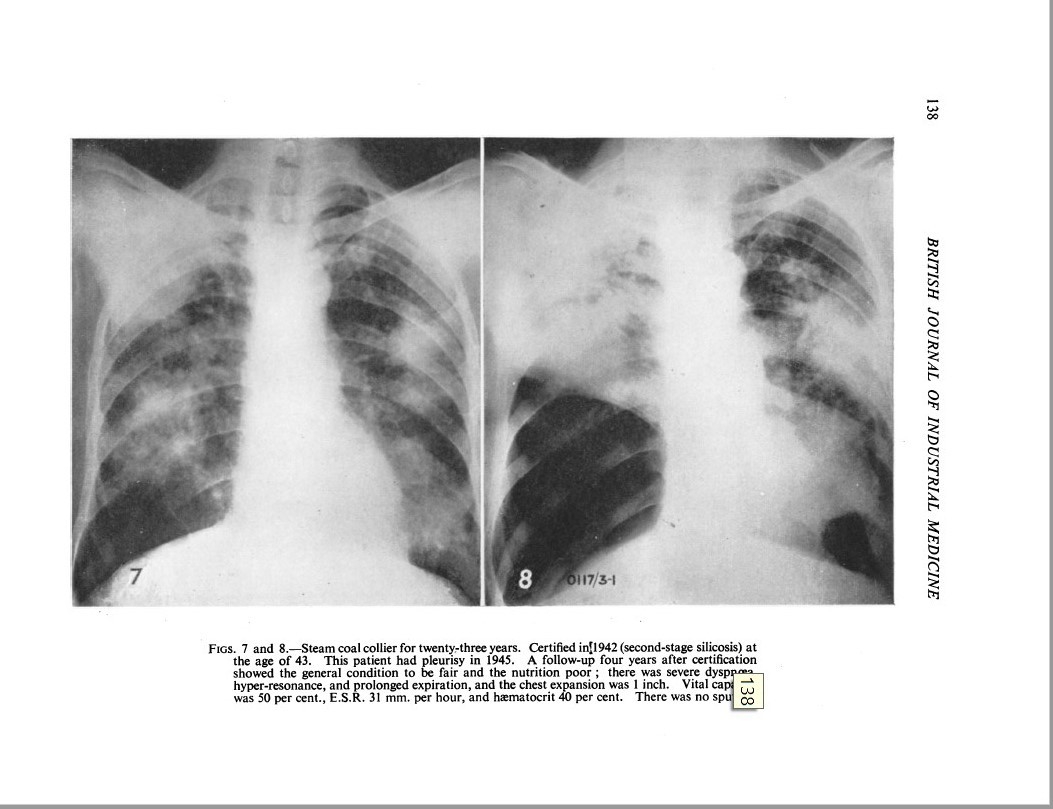

Towards the end of the war, Alice went to work at the newly established Department of Social Medicine in Oxford, headed by Professor John Ryle. She worked with the MRC Pneumoconiosis Unit, studying the effects of coal dust on the lungs of miners, a condition known as “black lung”. She later confessed that, to begin with, she had “despised” public medicine, which was in its infancy, but came to realise that “we are the survivors of slow-motion epidemics” that could be countered by small but transformative decisions made, especially in the workplace, to improve people’s health.

After the war, Alice became involved in the Oxford child cancer studies. From the 1930s onwards, the incidence of death in childhood cancer began rising. Initially it was believed that this was the result of better diagnosis, but by the 1950s, it was suggested that there might be an environmental factor involved. Alice began from the earliest stage, the foetus in the womb. She persuaded all the country’s local health departments to co-operate in interviewing the parents of every child dying of cancer or leukaemia, together with an equal number of control children. She published her findings in the British Medical Journal in 1958.

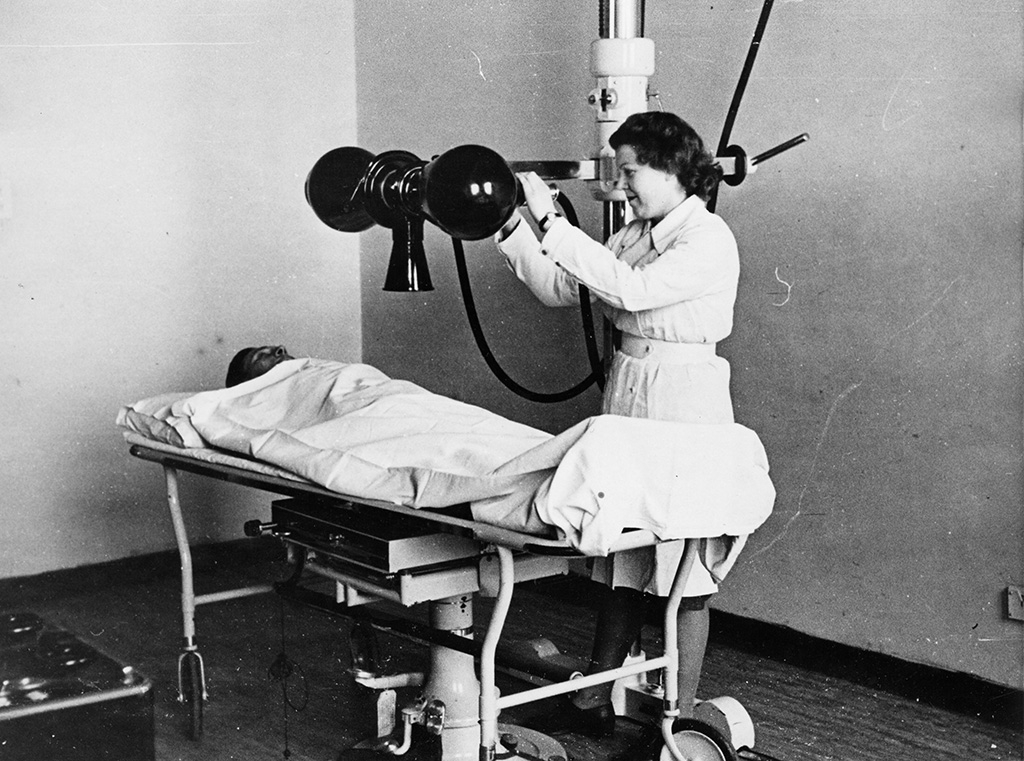

The results showed a clear connection between routine antenatal X-rays and the incidence of leukaemia in children. The report was met with outrage by many doctors. This was at the height of the Cold War, when governments were trying to build public trust in the “friendly atom”, and nobody wanted to accept that low-level radiation could kill children. As a result, she encountered difficulties obtaining funding for other studies.

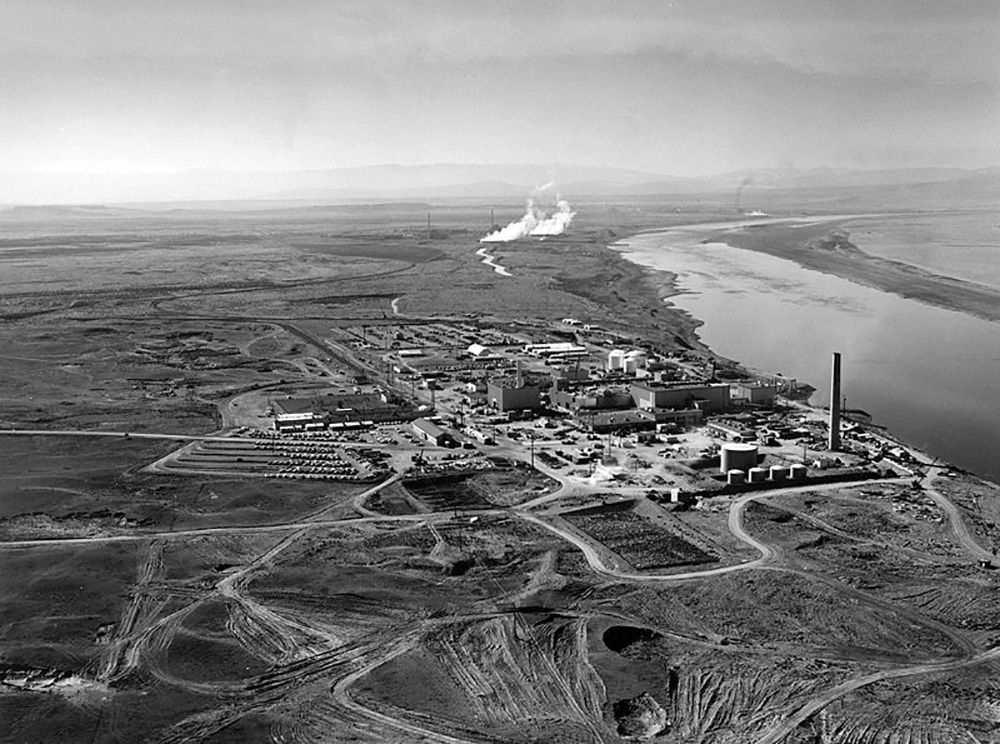

In 1974, when she was 70 and about to retire from Oxford, Alice was contacted by Dr Thomas Mancuso, who had been appointed by the US Atomic Energy Commission to study the health of workers in the Hanford plutonium plant. The findings of the Stewart-Kneale-Mancuso analysis (George Kneale was a statistician colleague) were startling, revealing a much higher rate of cancer among Hanford workers than predicted. As a result of the analysis, Mancuso lost his job and the US authorities withdrew their support. In spite of this, the Hanford survey continued, working with people living around the plant as well as workers.

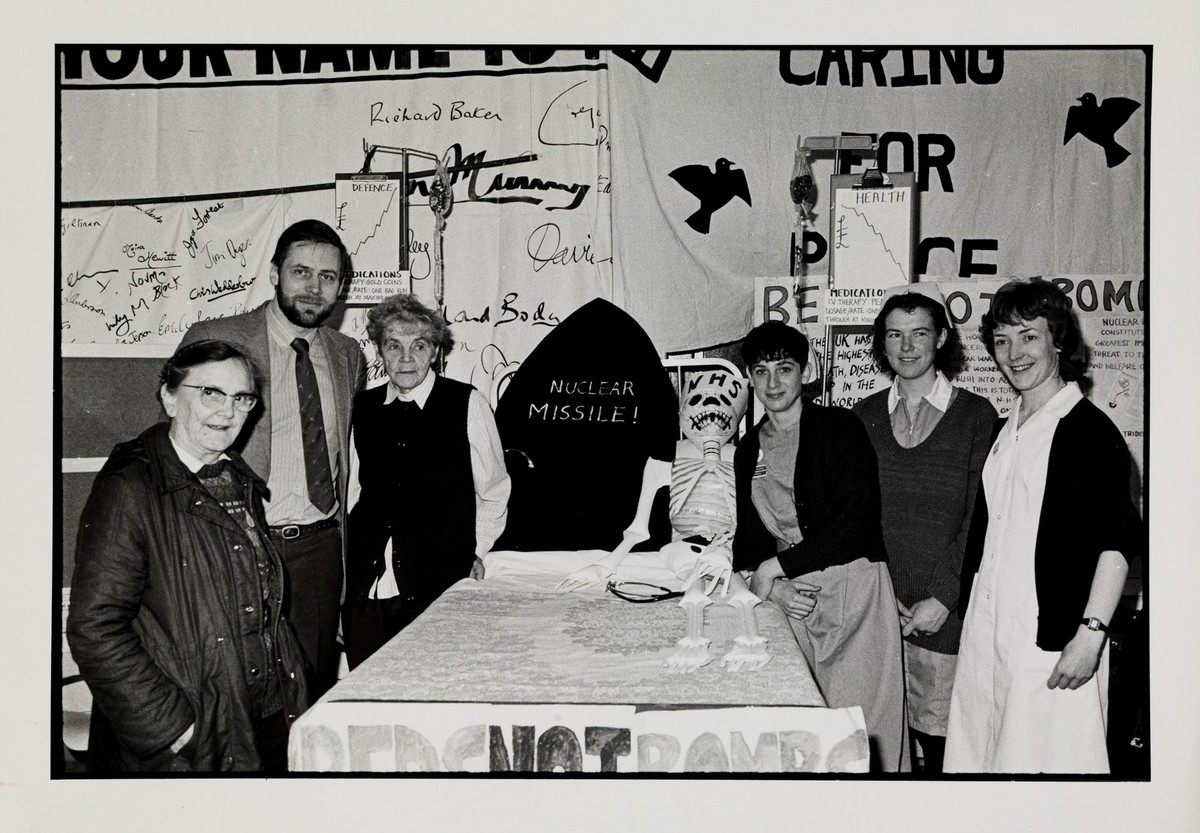

If the authorities dissociated themselves from her work, anti-nuclear activists were, unsurprisingly, open to Alice Stewart’s ideas. But she maintained a certain distance from them throughout her career. As she explained in her biography: “I wasn’t big on marching in demonstrations; I felt it was important that I not be an activist myself. I didn’t want my feelings about the nuclear issue to confuse my science, and I didn’t want to do anything that would jeopardise my credibility.”

Stewart was passionate about promoting the connection between low-dose radiation and cancer, and she was instrumental in getting the idea widely accepted. She was a brilliant and dedicated researcher, but her determination and tenacity also brought her into conflict with her peers and the authorities. In a 1995 interview she reflected on her struggles: “If I had been a man I would never have stood it; I would have gone,” she said. “The prospects were too bad, the pay too low. But being a woman, I didn’t have all that number of choices.”

Alice Stewart lived long enough to see her work universally recognised, but remained a controversial figure throughout her life. In 1986 (aged 80) she was awarded the Right Livelihood Award, the so-called “alternative Nobel Prize”, but the British Embassy in Sweden refused to send a car to take her to the ceremony. She remained characteristically defiant about her legacy: “Good people are seldom fully recognised during their lifetimes... One day it will be realised that my findings should have been acknowledged.”

About the author

Angela Saward

Angela is a research development specialist at Wellcome Collection with a background in film and sound archives. She has worked with artists and television producers on various archive-film-led projects. She co-curated ‘Here Comes Good Health!’ in 2012, and works with the exhibitions, publishing and policy teams on sourcing collections material.