Medieval texts, from Islamic medical treatises to Christian books of miracles, reveal surprisingly varied and complex experiences of blindness. But when medieval scholar Jude Seal experienced visual impairment themselves, they gained an even deeper understanding of the lives that they were studying.

I have been researching blindness in the Middle Ages for the last eight years, but I could not have predicted the insight I would gain into my historical research when, in early 2020, I found myself suffering from rapid sight loss.

By the time I was admitted for sight-saving surgery in 2021, I had lost all vision in my right eye and could distinguish colours and little else with my left. I found myself literally reading the medieval sources from a completely different viewpoint.

I was diagnosed as having rapidly forming cataracts in both eyes. I realised that I had been compensating for my weakening eyesight for at least a year, making various small changes to my daily life. I had changed the contrast on my laptop – eventually switching to using white text on a black background, I was using larger font sizes and my handwriting was larger.

This reminded me of descriptions in medieval miracle collections (accounts of miracles performed by saints or taking place at shrines to them), where an individual is described as experiencing worsening blindness, having been blind for several years. I wondered if they, like me, had been making these small adjustments without thinking.

As I went through the process of treatment, I found myself considering other ways in which blindness was experienced in the Middle Ages.

Medieval eye treatments

It may come as a surprise to learn that the medical treatments for sight loss, including surgery, appear to have been as routine and commonplace in the Middle Ages as today. The evidence of medical treatises and surgical instruments shows an unexpected degree of sophistication.

How effective these treatments were is a matter of debate, but research has shown that an eye salve used by Anglo-Saxon healers had antimicrobial properties, including against MRSA. Cataracts (clouding of the normally clear lens in the eye) were known to be a problem of the lens and removing the lens was understood as necessary to restore sight.

Some of the earliest medieval treatments for the diseases of the eyes were set out by the Islamic physician Ibn Sina (known as Avicenna in Latin texts) in his ‘Canon of Medicine’ (1025 CE). He used a system of categorising cataracts depending on their size, colour and density, and took the view that mild cases could be treated with medicine rather than surgery. Ibn Sina’s works were widely known in medieval medical schools across Europe and elements of his practice remained in use until the 17th century.

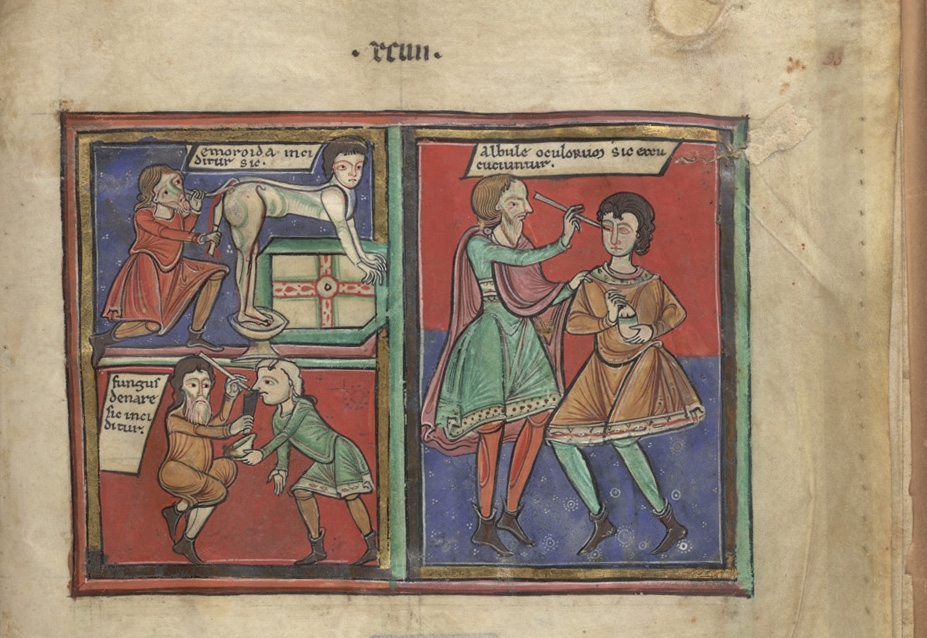

Three examples of medieval medical procedures, including (on the right) a man having a cataract removed. British Library manuscript Sloane 1975 f. 93, c. 1195 CE.

Surgery for cataracts was a commonplace medical procedure in many ancient cultures; indeed, cataract surgery is mentioned in the Babylonian code of law of Hammurabi in 1750 BCE. The first references to cataract surgery in Europe is found in ‘De Medicina’, the surviving section of a first-century CE encyclopaedia by Aulus Cornelius Celsus, a Roman physician about whom very little is known. The most common treatment for cataracts in both the ancient world and the medieval period appears to have been couching, which involved using a fine needle to push the clouded lens aside so that light could enter the pupil behind the lens.

Less common was the removal of the damaged lens via oral suction using a fine metal tube. The modern treatment of phacoemulsification acts in a similar way: the lens is broken down and aspirated from the eye before being replaced with an intra-ocular lens implant. This was what happened in my case.

When I came around in the recovery ward, I was overjoyed that not only could I read the notices on the opposite wall, but I could also see the different colours of the room and they were much richer. I can only imagine how this would have felt to a person in the Middle Ages, who would have been even less certain of whether surgery could improve their vision.

The blind experience in the Middle Ages

Historical medical texts and the remains of surgical instruments give us an insight into the understanding of blindness in the Middle Ages, but other sources are better for appreciating how people with blindness or visual impairment lived.

The lives of medieval saints and narratives of miracles can provide us with some interesting insights into these aspects of life in the Middle Ages. There is a longstanding assumption that people with visual impairments in the Middle Ages mostly survived by begging, but these medieval texts tell a different story, of such people who came to the shrines of saints from across the spectrum of class, profession and status. One example is a surviving passage from the ‘Book of St Foy’ that details a follower of the saint who left the religious life on losing his sight, and later struggled to return to it, as he was making a good living as an acrobat or juggler.

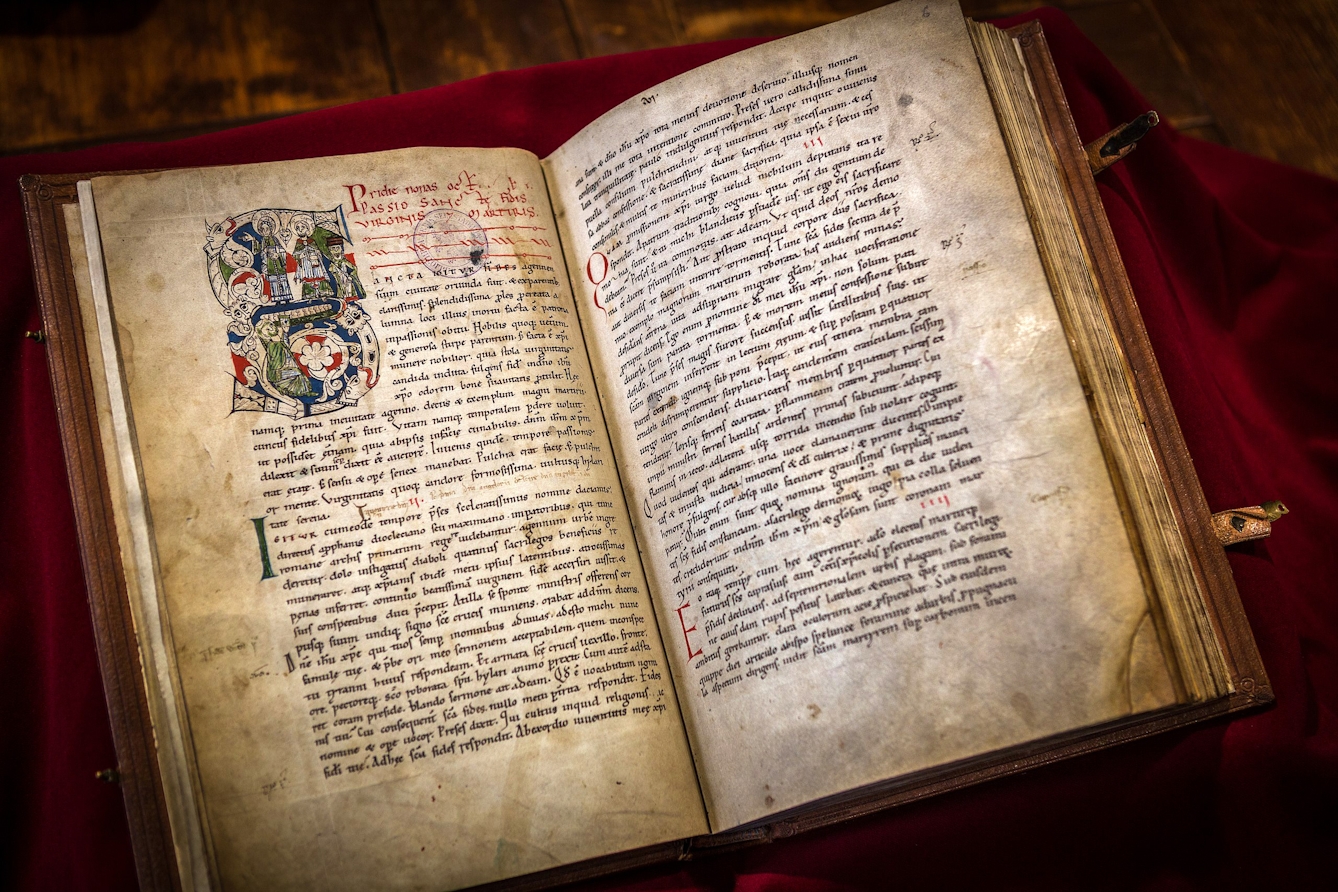

Bernard of Angers’ book recounts the miracles of St Foy, the little girl martyr, many of which tell humorous stories of this mischievous saint who wants nothing more than gold and jewels, and converts many in her actions to obtain them. ‘The miracles of Saint Foy’ by Bernard of Angers, c. 1013–1020 CE.

The texts also show that blindness was not just the result of illness or accident. Blinding was used as a punishment for various crimes in the Middle Ages and sometimes natural occurences were also attributed to Divine punishment, carried out by saints.

Examples of punishment include knights blinded for hunting on abbey lands on a holy day in the Miracles of St Edmund, and the loss of eyes for blasphemy in William of Canterbury’s miracles of Thomas Becket. In some cases, the saint would subsequently heal the individual; in others they were left blind.

This did not mean that all people with visual impairments were automatically judged to have sinned in some way or to have been punished by the secular authorities.

Support for blind people

There were many different structures that provided support to people with blindness or other visual impairment, and the most significant of these, then, as now, was the family. Some people survived on the charity of others, and those with crafts and skills that they could continue to use supported themselves. Many were able to engage in society in the same way people with visual impairments do today.

As the process of making saints became increasingly formulaic and legalistic in the Church, evidence of miracles increasingly required testimony from those who knew the blind person before they were healed. This leaves us with useful evidence about where and how people found support in the Middle Ages. Some individuals formed communities or travelled in groups. The miracles of Saint Swithun describe a group of more than 12 blind people who came to the shrine together. Others were guided by family members or friends.

Jesus heals a man born blind. From a Flemish book of hours (Liège), c. 1250–1300.

Another case from the miracles of St Swithun describes a mute woman acting as guide to a blind woman, who in turn acts as her voice, and another a group of three blind women from the Isle of Wight who become lost travelling into Winchester, until they find a mute man willing to guide them.

The histories of disability are complex, and researching them is challenging, but they are of fundamental importance to understanding society both in the past and the present. My own experience of blindness gave me a much greater understanding and insight into the daily lives of the people I have found through my research – something I would probably never have gained had I not, temporarily, been blind myself. Appreciating how attitudes to disability have formed and changed over time is vital if we are to break down barriers to inclusion today.

About the author

Jude Seal

Jude Seal is a PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London, researching the cultural perceptions of blindness, deafness and mutism in English miracle literature between 1070 and 1450. Their research explores the intersection of the histories of medicine and magic, and the archaeology of disease. They also write on living with a brain injury and chronic pain, and in their spare time are involved in disability sport.