Ben Falk developed obsessive-compulsive disorder as a teenager and now has children of his own. Here he explores whether the condition is heritable, and how he can help his daughters cope well with their worries.

Of all the things that made me nervous about becoming a father, the fact it might cause my obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) to spiral was near the top of the list. In close second place was the fear that my children would inherit the condition.

Since I was 14, I’ve spent a lot of my life counting how many times I’ve touched or looked at things. I carry out these compulsions not because I want to, but because if I don’t, the obsessions tell me “bad things will happen”.

I sought treatment about 16 years after I presented symptoms, a little more than the average 12-year wait, and my condition has improved, I think. But OCD is sneaky. It finds ways to inveigle itself into your life. Mine is still with me all day, every day.

Any parent knows that it’s very hard not to be scared about something happening to your child. When you have OCD, you carry out compulsions to provide a sense of control, so it’s not surprising I wasn’t able to stop. The irony is that OCD doesn’t put you in control – quite the opposite, in fact. It makes me feel utterly rudderless.

“Any parent knows that it’s very hard not to be scared about something happening to your child. The irony is that OCD doesn’t put you in control – quite the opposite, in fact.”

“It’s not the sort of thing you talk about in your NCT group,” agrees Dr Fiona Challacombe, a clinical psychologist and expert in OCD at King’s College London.

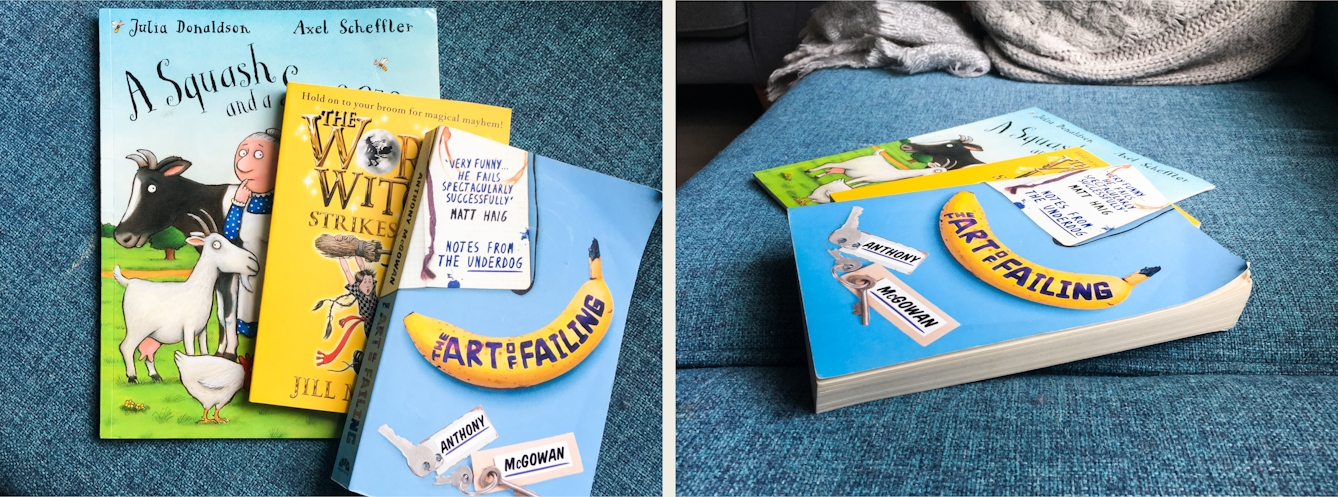

My eldest daughter is six and she has a three-year-old sister. Who knows what’s really going on in their brains? The older one? Sure, we read ‘A Squash and a Squeeze’ every night for 18 months, but children love and rely on routines – one of the reasons why, explains Professor Karina Lovell, a professor of mental health at the University of Manchester, “There’s always been a shying away from [diagnosing] under eight, because it’s so difficult to work out if the child has got OCD or if it’s a normal part of development. What we don’t know is who grows out of that and who doesn’t.”

Looking out for signs of OCD

What I can see is my youngest getting annoyed when the Velcro straps on her shoes aren’t exactly aligned, or how she has to tuck both sides of the duvet in a specific way when she climbs into bed. To me it seems – I don’t know – a bit different. That’s difficult to watch, especially when, as Fugen Neziroglu and Yvette Fruchter from the Bio-Behavioural Institute in New York write, “Children may not necessarily recognise the irrational nature of their OCD symptoms and may not describe them as upsetting.”

What if she’s like me but doesn’t know it yet? What if one of the things she’s inherited from me, alongside my blue eyes, is my weird mental health tendencies? OCD tends to first manifest in early adolescence (around 10–12) but, as Professor Lovell says, “When I’ve spoken to young people, they’ve often known there was something they often describe as ‘not quite right’ for a while.”

“What I can see is my youngest getting annoyed when the Velcro straps on her shoes aren’t exactly aligned, or how she has to tuck both sides of the duvet in a specific way when she climbs into bed."

“If you have an anxiety disorder, your child might be a bit more vulnerable to an anxiety disorder, but I wouldn’t ever specify which one,” she continues.

“There is a heritability for almost everything, but in terms of the absolute risk, it’s still quite low,” says Dr Challacombe, “[but] it’s understandable your filter would be at a different level.”

Did my youngest pick up on a compulsion I wasn’t even aware of and synthesise that into her own behaviour?

Yes, my filter. Because of my condition, I’ve started to believe I can and, indeed, kind of want to spot a fellow sufferer from a mile away, like beeping my horn and waving when I see someone driving the same make of car. I know what symptoms can look like and am hyper-aware. That’s a problem, as studies suggest that parents who either have OCD or know someone with it could well over-report their children’s behaviour.

“Because of my condition, I’ve started to believe I can and, indeed, kind of want to spot a fellow sufferer from a mile away.”

“I would be really cautious about pathologising anything until you have a lot more evidence,” Dr Challacombe tells me. “Every OCD parent’s worst fear is that their child might get it, that, ‘I’m going to give it to my child.’ None of these things are very likely… there isn’t a gene for OCD.”

Nevertheless, I’m currently still slave to my compulsions, and while OCD sufferers are clever about hiding their problem (most of my friends and family had, or have, no clue), I worry it unconsciously seeps into my daily life, in front of children who are particularly attuned to feelings and emotions. Did my youngest pick up on a compulsion I wasn’t even aware of and synthesise that into her own behaviour?

Healthy ways to deal with risk

A 2018 study in the Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry about children with OCD who have a first-degree relative with it too throws out sentences like, “We speculate that these families must have a particular dynamic or environment that facilitates or is more conducive to the development or maintenance of psychopathology in the offspring.” That’s not the sort of house I want to live in.

“Think about what kind of messages overall you want your kids to have about themselves and the world and so on,” says Dr Challacombe. “It’s okay not to be perfect with your OCD stuff; you can tolerate uncomfortable feelings… what matters is your actions.”

“While it’s tempting to concentrate on external solutions, the most important thing I can do right now to help my kids’ mental health is deal with my own. Properly.”

OCD makes you believe you’re inoculating yourself from the perils of the world. But the reality is we live a life full of risk, from driving a car to getting a serious illness. As Professor Lovell suggests, we do children a disservice by telling them everything will be okay; we should focus on explaining what we do to mitigate these everyday risks instead.

Then we can more effectively interrogate why a child is doing something (like with my daughter’s shoes or duvet), what they might be frightened of and start gently challenging risk-averse behaviour so it doesn’t escalate. It seems to me that might be the closest thing we have to a ‘vaccination’ for anxiety disorders like OCD.

Ultimately though, while it’s tempting to concentrate on external solutions, the most important thing I can do right now to help my kids’ mental health is deal with my own. Properly.

“People are like, ‘If I could just get rid of these OCD thoughts, I would be normal,’” says Dr Challacombe. “But what happens in OCD is that people have become way too focused on their thoughts. It’s like, ‘You are normal: you just need to have a different relationship with these thoughts.’”

Challenge accepted… (*rolls up sleeves*).

About the author

Ben Falk

Ben Falk is a freelance writer, author and academic. He wrote the definitive biography of Robert Downey Jr and spent two years in Los Angeles as PA Media's Hollywood bureau chief. More recently, he has also started writing about male mental health, borne out of his personal experience with OCD. Highlights of his professional career include nearly getting punched by Mickey Rourke and reporting on the Oscars.