The Samaritans was one of the first phone helplines dedicated to reducing the feelings of isolation and disconnection that can lead to suicide. The charity was built on the principles of being non-judgemental and there to listen. But what happens when a caller is looking for something more than conversation?

Befriending heavy breathers

Words by Mel Grantphotography by Phillip Jobaverage reading time 10 minutes

- Article

One of the best parts of working in Collections Development at Wellcome Collection is acquiring material that challenges the way we think and feel about health. Every acquisition is a discovery and a chance to learn about what makes us human. When we acquired a rare surviving copy of an instructional manual published by the Samaritans in the 1970s, I learned the surprising story of how charity volunteers tried to deal with telephone masturbators.

The Samaritans, which offers support to anyone in emotional distress, was founded in 1953 by Chad Varah (1911–2007). But only two years after the phone helpline was set up, a significant number of men were calling to masturbate. As the problem grew, it became apparent that a system was needed to deal with these obscene callers.

Varah appropriated a special phone number that had been used for direct calls between the Brent and central London branches, and specific volunteers were trained to take these calls. If one of these volunteers had to be fetched to take a call, they were asked to come and take a “Brent call”. The volunteers at the Brent branch were horrified: they didn’t want their branch name associated with this filth!

To placate them, Varah switched the name to “Brenda”, and from then on, obscene callers were referred to as “Brenda callers”. The “Brenda befriending” manual that we acquired was written by Varah and given to the volunteers to provide guidance on how to handle different types of heavy-breathing caller.

Nancy in the Samaritans' phone room. From the series ‘First Duty’ by Phillip Job, 2017.

We expect manuals to be stripped of personality, the voice of the writer being neutral. But this is different; Varah’s voice, his opinions, his experience and tone come through loud and strong. Varah’s writing can be in turn hilarious and terrifying, and there are moments of empathy when referring to those who are lonely and marginalised. He even includes a page of cartoons at the end of the manual to challenge your sense of humour!

Varah was an Anglican priest and sex therapist who wrote articles for ‘Forum’, a supplement to the soft-porn magazine ‘ Penthouse’. There didn’t seem to be anything that could shock him: he approached sexual matters from a position of being non-judgemental and he was very open to discussing subjects that others might shy away from, including what motivated telephone masturbators.

The men who made obscene phone calls

According to Varah, there were several reasons why someone might want to make an obscene call: to have a sexual chat, to annoy people, or to cause distress (particularly to women). Varah subdivided callers into those who are “befriendable”, who need help and can be helped, and those who are “unbefriendable”, such as manipulative psychopaths.

Varah’s categories of caller and the guidance on how to help them is fascinating. I’ve summarised them below, but as this was the 1970s, the language and definitions may not be what we would use now.

Annie in the Samaritans' phone room.

As we might expect, one group of problem callers were those calling for a laugh. These were often boys calling for information about sex, taking advantage of the opportunity to discuss it, which could lead to masturbation. If phone lines were not busy, volunteers were encouraged to engage with them and see it as an opportunity to teach them something useful about sex and not be put off by the masturbation.

But most of the callers were taken seriously as people who needed help. One such group of callers were lonely men who were afraid of women and unable to make relationships with them. Brenda volunteers were trained to teach them to understand women in a sisterly way, so the caller would begin to respect women and stop fearing them.

Most of the callers were taken seriously as people who needed help

Varah had a lot of sympathy for what he described as “fetishists and transvestites”, believing that they often suffered from loneliness and that the Brenda volunteer might be the only person they could fully confide in. He believed that fetishists were ruled by their interest and unable to form proper relationships because of it. Volunteers could encourage these callers to grow and have sex with others, which Varah saw as great progress. For transvestites, or what we would now refer to as cross-dressers, Varah’s approach was to reassure them that their pleasure was legitimate.

Another category was “sado-masochists”. Varah’s instruction was to listen to their stories of humiliation, which may include masturbation, and then put pressure on them to see an expert. To Varah, “the masturbation is part of a whole movement towards greater self-approval and confidence”.

Sandra in the Samaritans' phone room.

A group of callers including “exhibitionists and the related voyeur” fell into several subcategories. Some threatened that unless the volunteer said something obscene, they would expose themselves and get arrested. Other callers might state that they didn’t want to speak to a volunteer face to face, as they may expose themselves. Varah saw this as the caller seeking permission, and recommended that they should not be indulged. Both groups should be encouraged to come in for counselling, and if allowing masturbation encouraged them to do so, then this could be used as a tool.

A final subset of this group were young men whose mothers never accepted their sexuality or masculinity, and who exposed themselves to women of a motherly age and type. Varah recommended that such callers were to be given reassurance, particularly if they were young, before they got themselves into trouble.

The final category, the manipulative psychopaths, shows Varah’s flair for language and drama:

There are people who give you that sudden shudder of recognition of madness; the people with whom you feel that departure from reality, that sense that they inhabit a horrid private universe which you can’t enter.

For these Varah advises:

If he wants to masturbate, you help him do so in the best way you know how. If he becomes very interested indeed in the volunteer to the point where he might be willing to come round [to the branch for therapy], then she must utilise that fact to get him to come, but be very careful to let the rest of us know he might be coming.

Francesca in the Samaritans' phone room.

Who were the Brenda volunteers?

According to Varah it took a particular kind of woman to deal with Brenda calls. And they were all women. Varah discusses the suitability of women for this role due to being “more slowly aroused” than men: “Brenda’s hand is more likely to be patting a yawn or searching for the client’s index card than feeling in her knickers for her clitoris.”

Also, apparently most of the callers were men demanding to speak to women and would mostly put the phone down if another man answered, so volunteers had to be women. Varah describes the work as a “unique therapeutic task” and Brenda volunteers as having “openness, tolerance, gentleness and humility in outstanding measure”. A Brenda volunteer may be the only friend to someone who has, will, or says they have done something terrible. And this is important. It may mean listening to “very unacceptable ideas and to care about sometimes rather alarming people”.

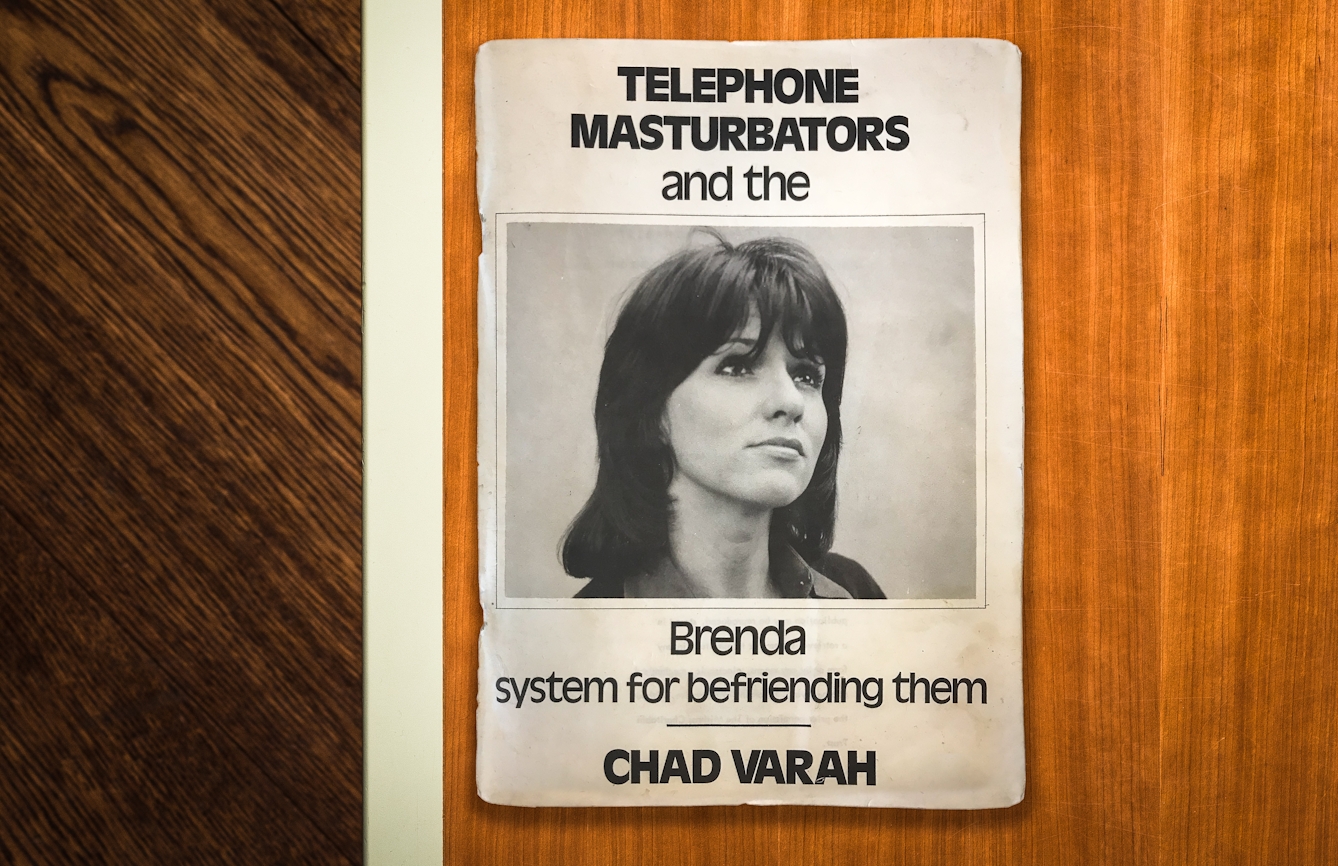

A rare surviving copy of an instructional manual published by the Samaritans in the 1970s.

Looking at the cover of the manual, I wondered about the image on the front, and whether the woman staring wistfully into the distance was an original Brenda. Flicking through Varah’s autobiography, suddenly I saw her image again. The face of Brenda was Varah’s secretary, Suzan Cameron.

Cameron played a crucial role in the development of the Brenda system, helping to identify and block repeat callers. Some callers could be manipulative to get the sexual gratification they sought. There are several examples of calls and many individual case studies in the manual, some of which can make for difficult reading.

Some callers could be manipulative to get the sexual gratification they sought

Dealing with these calls must have impacted on the mental health of the volunteers, and Varah made it clear that volunteers should be able to share and offload. He recognised that providing a workplace that safeguarded the mental health of its staff was vital if they were to undertake this work.

Debbie in the Samaritans' phone room.

The end of the Brenda system

The Brenda system became controversial within the Samaritans, as some felt the Brenda volunteers were ‘gratifying’ the masturbators rather than helping them. Varah, in turn instructed that:

Women volunteers, who (doubtless, for good and sufficient personal reasons) do not offer to learn to take Brenda calls, should be asked to give moral support to those who do take them, and not permit contemptuous and inapplicable words like “unpaid prostitutes” to be applied to the Brenda system without being challenged and debated.

“Unpaid prostitutes” became a common criticism of the system, and sexism and prudishness around exposing women to obscenity amplified the issue within the Samaritans. In Varah’s autobiography ‘Before I Die Again’, he discusses how “the Executive [of the Samaritans] laid down a policy of trying to block what were prudishly described as ‘M-calls’”, ‘M’ meaning masturbation. He continues: “The ridiculous situation arose where the Samaritans were willing to listen calmly to tales of murder, massacre, mayhem, matricide and any other M except masturbation.”

Varah retired from the Samaritans in 1986 and a year later they abandoned the Brenda system, but Varah always believed this was a mistake. It fractured his relationship with the organisation he founded. Dropping the Brenda system was one of several reasons that drove Varah in 2003 to a failed attempt at getting the Charity Commission to strip the Samaritans of their charitable status.

Kirsty in the Samaritans' phone room.

The ‘M-callers’ today

Today the Samaritans takes a zero-tolerance approach to calls from people who are seeking sexual gratification, as well as those who are abusive to the volunteers. All volunteers are trained to end calls seeking to misuse the service, and the organisation bars those numbers from accessing the service.

It is impossible to say if the Brenda system worked. Varah claimed it did, but he was obviously biased. And many branches claimed it didn’t, although he contested that they hadn’t set the system up properly, so it was not the system’s fault. Irrespective of the effectiveness or not of the Brenda system, it’s undeniably problematic when sexual acts are incorporated into a service that is there to assist those in mental distress, whatever bigger-picture outcome Varah hoped for.

Wellcome Collection acquired the Brenda manual because it forces us to consider what it means to help people, who is deserving of help and how far we might go to support them. The manual touches on subjects that are just as relevant today as they were in the 1970s: mental health, attitudes to gender, sexuality, sex education, disability and sex work, among others. Whatever you might think of the Brenda system, Chad Varah defiantly challenges us to look directly at our own attitudes and boundaries.

This article was amended on 4 September 2024 to reflect the Samaritans’ current approach to nuisance and abusive calls.

About the contributors

Mel Grant

Mel Grant develops Wellcome Collection’s unique and distinctive collections. Mel has a passion for thinking critically about what materials are preserved in collections and representing marginalised voices within them. She has a particular interest in creative expressions of lived experience of health such as art, zines and graphic medicine.

Phillip Job

Phillip Job is a London-based photographer whose documentary work focuses on mental health and those who provide emotional support. His project ‘First Duty’, a photographic study of the Samaritans, has been exhibited in several venues across London. He is also a founding member of Chamber, which most recently organised the pop-up exhibition ‘Safe As Houses’, about domestic abuse victims around the world, and a charitable print sale, ‘Prints For Food’.