One coping strategy when we face a crisis like Covid-19 is to document our experiences in some way, whether that’s on social media or in an old-fashioned diary. Samuel Pepys, a young civil servant living in London, recorded his daily life for almost ten years in the 1660s. Find out how he and the city reacted to the Great Plague in 1665 – the worst epidemic to hit England since the Black Death of 1348.

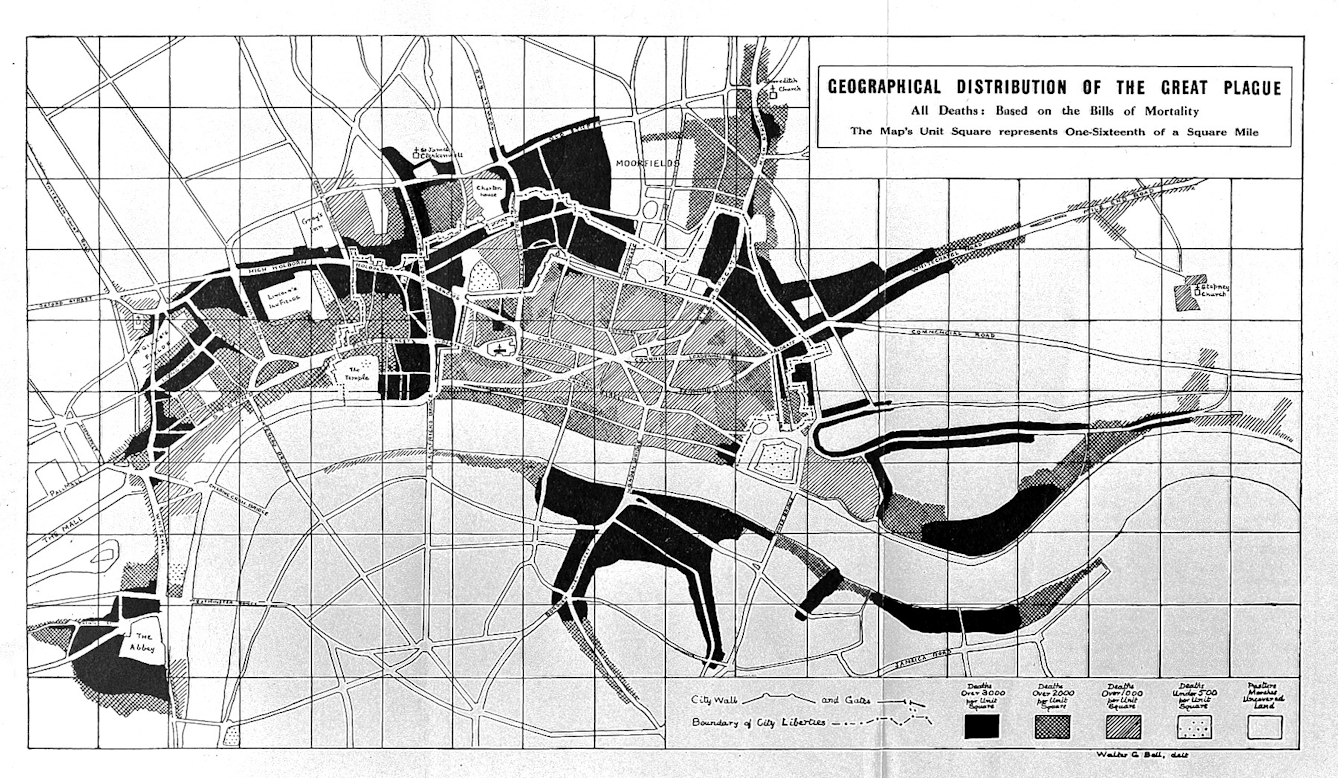

The first major plague outbreak in Europe was in the 14th century. It peaked between 1347 and 1351, and some places, like Florence in Italy (pictured), did not fully recover their pre-1300 population levels until the 19th century. In early 1665 a new outbreak hit St Giles, an area that back then was just outside London; today it’s near Covent Garden. Cassell’s ‘Illustrated History of England’ describes how: “In May it burst forth with frightful violence in St Giles, and, spreading over the adjoining parishes, soon threatened both Whitehall and the city.”

To try to stop the spread of plague, a team of watchmen drew a red cross on the doors of houses under quarantine. Anyone found to have escaped quarantine was treated as a felon and could face a death sentence. On 7 June 1665, 32-year-old civil servant Samuel Pepys wrote of the horror of encountering the red crosses: “This day, much against my Will, I did in Drury lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and ‘Lord have mercy upon us’ writ there – which was a sad sight to me, being the first of that kind that to my remembrance I ever saw. It put me into an ill conception of myself and my smell, so that I was forced to buy some roll tobacco to smell to and chaw – which took away the apprehension.”

The quarantine did little to stop the spread of the plague. On 26 June Pepys writes in his diary that “the plague encreases mightily”. One month later, on 20 July, he laments: “But, Lord! To see how the plague spreads.” London was facing an epidemic.

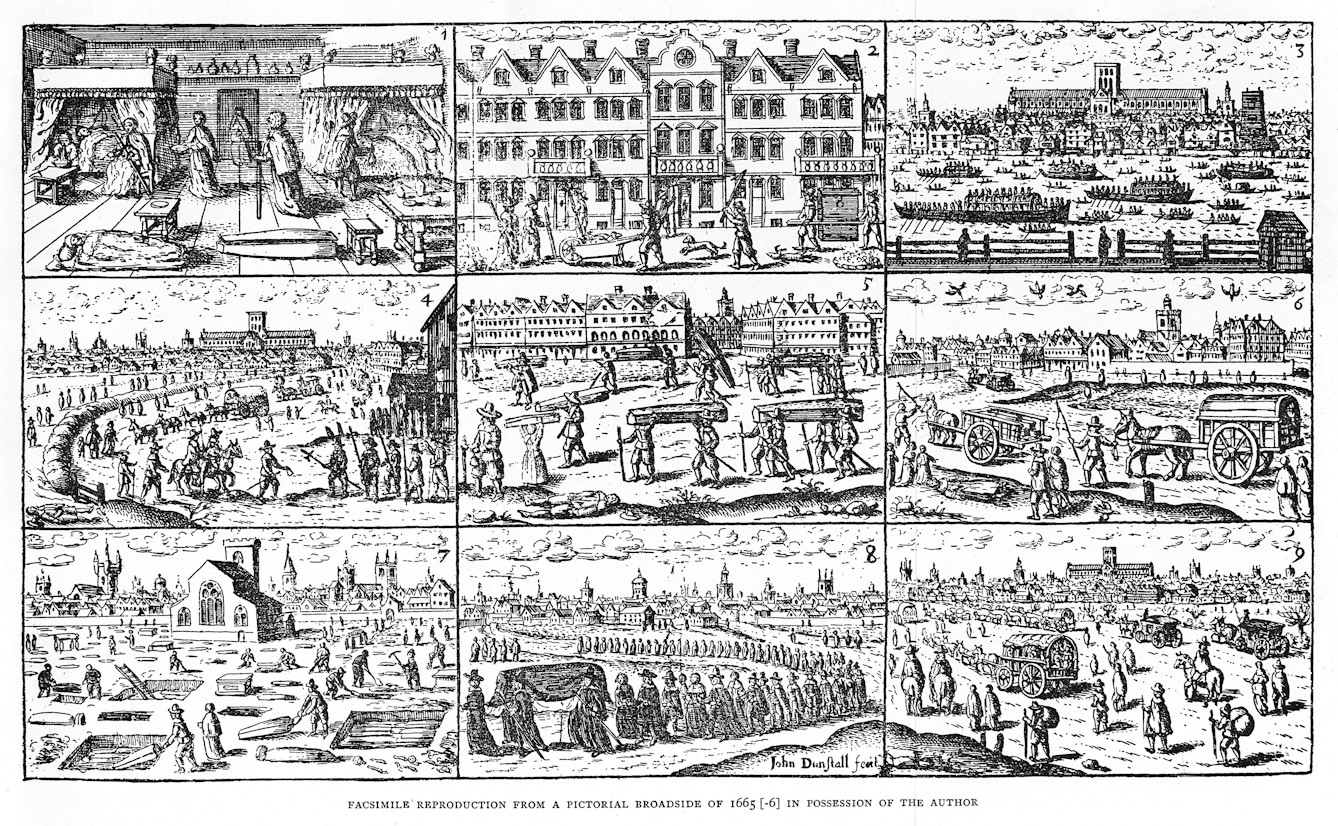

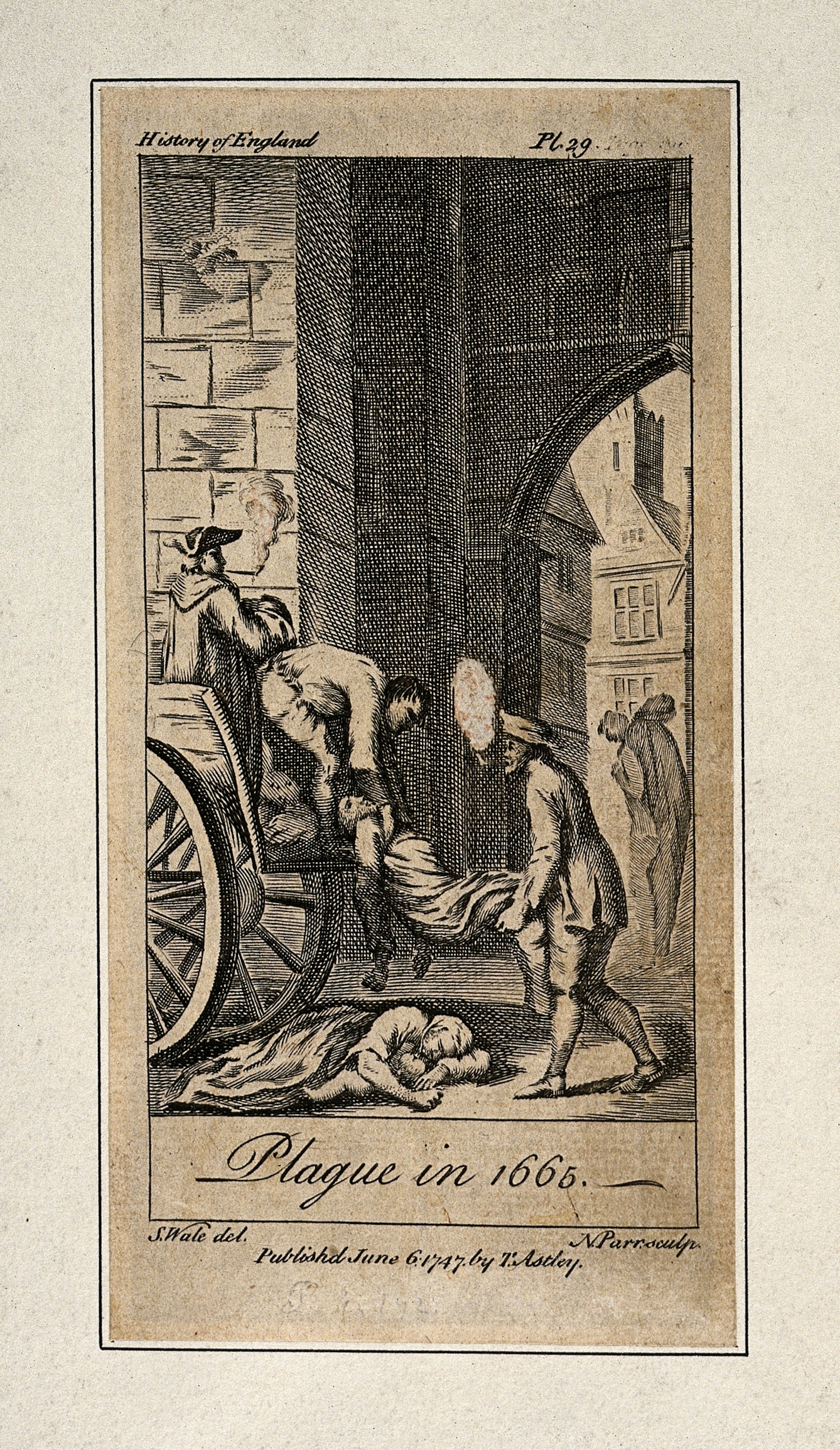

By August, burials began to take place during the day, rather than just at night. Pepys notes on 12 August: “The people die so, that now it seems they are fain [obliged] to carry the dead to be buried by daylight, the nights not sufficing to do it in. And my Lord Mayor commands people to be within at 9 at night, all (as they say) that the sick may have liberty to go abroad for ayre.” Many people thought the plague was caused by bad air quality, which is why the infected were told to go out for air during the night-time curfew.

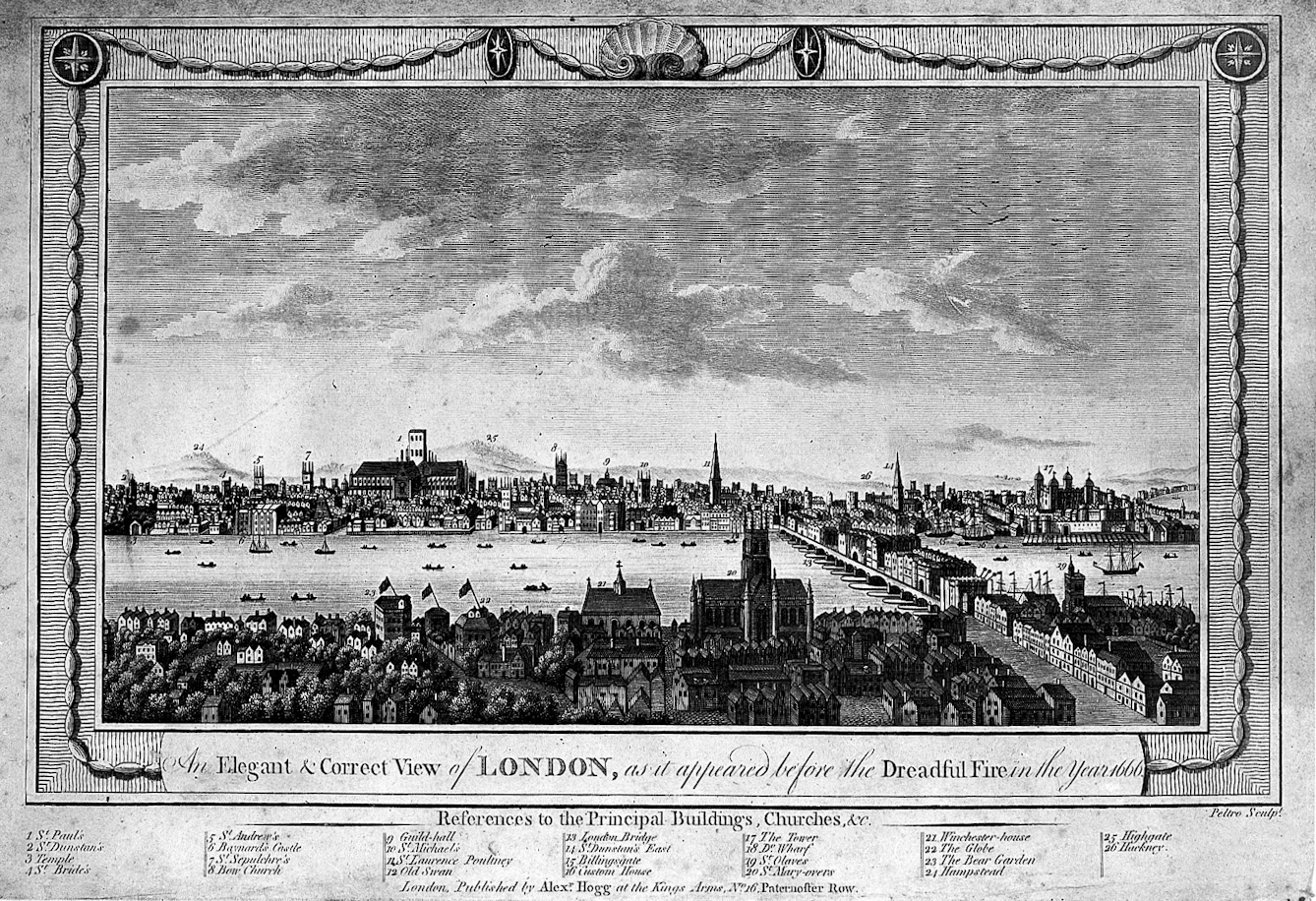

The epidemic emptied London’s streets. The nobility fled to the country, and the King and his court retreated to Salisbury. On 16 August 1665, Pepys writes that “two shops in three, if not more, [are] generally shut up”. Later in the year, on 16 October, he laments the eerie desolation of the city: “But, Lord! How empty the streets are and melancholy, so many poor sick people in the streets full of sores; and so many sad stories overheard as I walk, everybody talking of this dead, and that man sick… And they tell me that, in Westminster, there is never a physician and but one apothecary left, all being dead.”

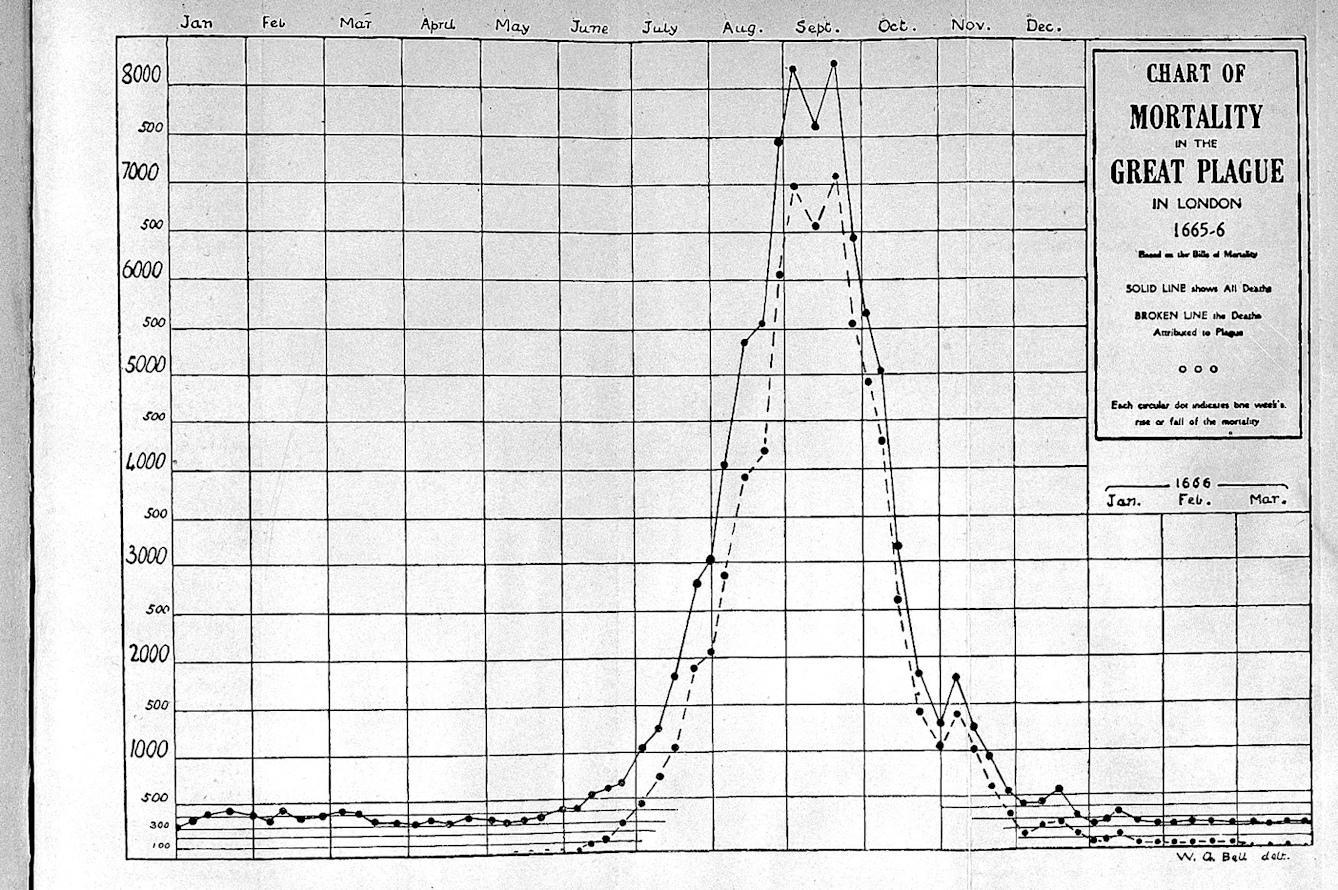

The public were both saddened by the increase in cases and fearful that the number of deaths had been under-reported. On 31 August Pepys writes: “Thus this month ends, with great sadness upon the public through the greatness of the plague, everywhere through the Kingdom almost. Every day sadder and sadder news of its encrease. In the City died this week 7,496; and of them 6,102 of the plague. But it is feared that the true number of the dead this week is near 10,000 – partly from the poor that cannot be taken notice of through the greatness of the number, and partly from the Quakers and others that will not have any bell ring for them.”

Periwigs were very fashionable, and ever the trendy young professional, Pepys had his head shaved and first wig fitted in 1663. Two years later, Pepys noted that the plague was likely to affect periwig sales: “It is a wonder what will be the fashion after the plague is done as to periwigs, for nobody will dare to buy any haire for fear of the infection – that it had been cut off of the heads of people dead of the plague.” But for Pepys, fashion trumped fear – on 3 September 1665 he put on a “new periwig”, even though “the plague was in Westminster when I bought it”. He decided that as it had been “a good while since” the purchase, he could now safely wear his new accessory.

On 6 September, Pepys writes: “I looked into the street and saw fires burning in the street, as it is through the whole city by the Lord Mayor’s order.” The fires were thought to have a purifying effect on the air quality, and thus many thought they would rid the city of the plague. The fires were everywhere: “All the way fires on each side [of] the Thames.”

On 15 September 1665 Pepys describes meeting his friend Captain Cocke after work, and of them having “drank a cup of good drink”. While they drank, London faced the peak of the epidemic, as shown by the graph above. Pepys was keenly aware of the numbers – his diary is full of detailed notes on increases and decreases in the numbers of cases and deaths. In fact, he sees the increase in deaths as justifying his drinking: “I am fain to allow myself [alcohol] during this plague time… my physician being dead.” Then, as now, alcohol was a method of coping.

By the autumn it became hard to imagine life without the plague. Bodies piled up on carts. On 7 October Pepys writes of how he “comes close by the bearers with a dead corpse of the plague; but Lord, to see what custom is, that I am come almost to think nothing of it”.

Mercifully, towards the end of the year the number of cases began to drop. On New Year’s Eve, Pepys writes: “Now the plague is abated almost to nothing… to our great joy, the town fills apace, and shops begin to be open again. Pray God continue the plague’s decrease.”

Pepys’s prayers were answered. In February 1666 London was deemed safe enough for the king and his court to return. Life slowly resumed. Pepys finally made it back to the theatre in late October: an avid reader of playscripts, he had been deprived of the opportunity since 5 June 1665, when mass entertainment like theatres and football matches were ordered to cease. Ironically, a minor illness, combined with bad acting and poor acoustics, meant he didn’t enjoy it: “The first play I have seen since before the great plague… [but] the whole thing done ill, and being ill also, I had no manner of pleasure in the play.” He saw another production in early December, which was, thankfully, much better: “And so to the King’s playhouse… and saw the remainder of The Mayds Tragedy – a good play, and well acted.” Phew!

About the author

Surya Bowyer

Surya Bowyer is a writer and educator from London. He is interested in the intertwined histories of media and technology.