Artist Anthony Luvera collaborated with transmasculine and non-binary people to explore their views on masculinity and how their experiences have developed over different stages of their life. Using personal photographs as a starting point, their conversations address upbringing, male privilege, the body, race, name-changing, the family, and the politics of identity.

Transitioning and the family album

Artwork by Anthony Luveraaverage reading time 17 minutes

- Photo story

In the Spring of 2019, I sent out an invitation to transmasculine and non-binary people to explore the theme of masculinity with me. I shared information through friends, colleagues, online groups and social media platforms, and attended support groups and social meetings across the country. I explained my intention was to find a way to collaborate in the creation of photographs, sound recordings, and text, that would represent their points of view and feelings about masculinity.

People got in touch from across the country, from Lancing to Lancaster, and Nottingham to London. I asked individuals to meet with me and to bring their personal photographs to use as the starting point for recorded conversations. I invited them to make a portrait that would best reflect how they would like to be represented. We then made selections from our discussions to be transcribed onto the photographs.

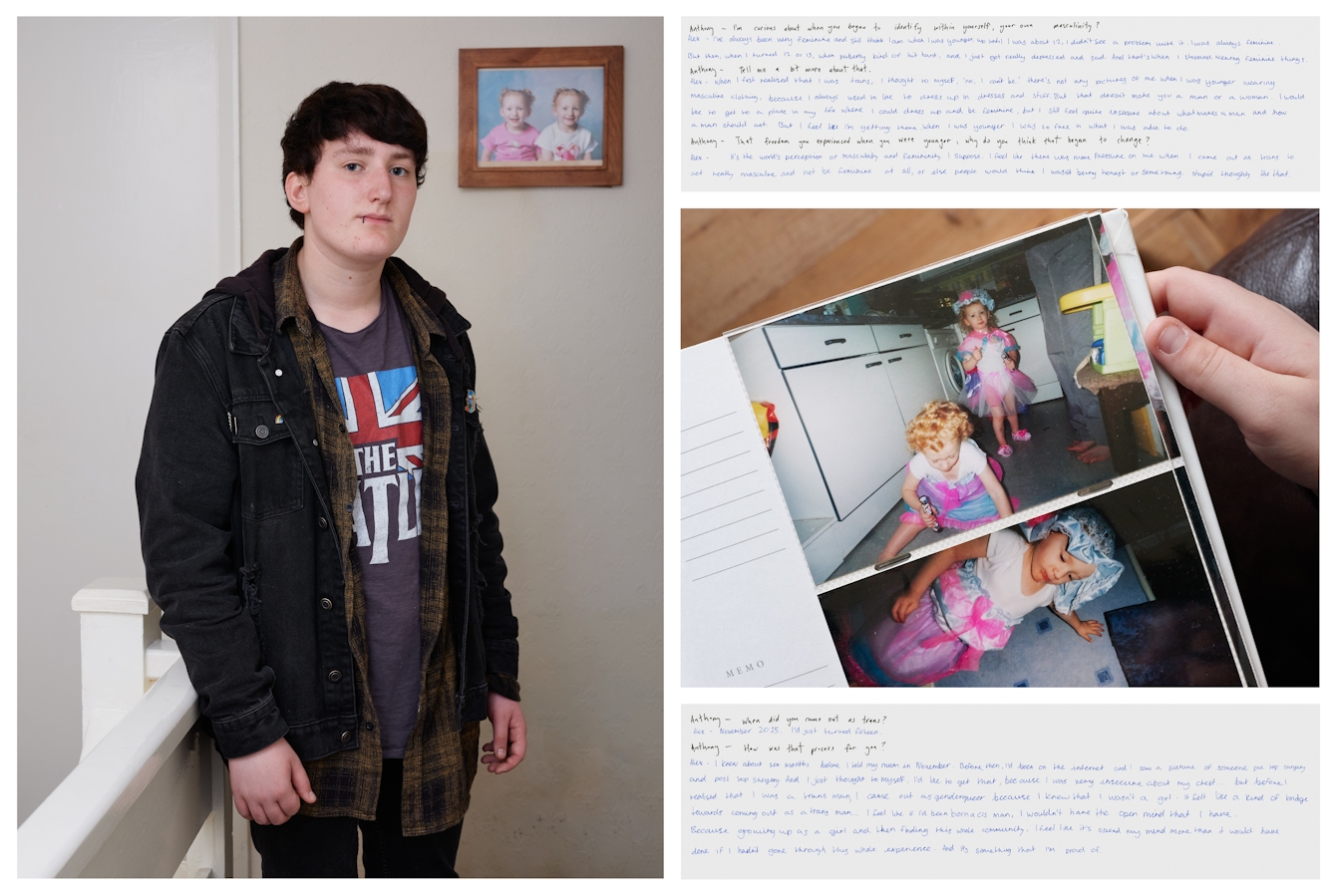

Alex

Alex from In Conversation by Anthony Luvera.

Anthony: I'm curious about when you began to identify within yourself, your own masculinity?

Alex: I've always been very feminine and I still think I am. When I was younger, up until I was about 12, I didn't see a problem with it. I was always feminine. But then, when I turned 12 or 13, when puberty kind of hit hard, I just got really depressed and sad. And that's when I stopped wearing feminine things.

Anthony: Tell me a bit more about that.

Alex: When I first realised that I was trans, I thought to myself, ‘no I can't be.’ There's not any pictures of me when I was younger wearing masculine clothing, because I always used to like to dress up in dresses and stuff. But that doesn't make you a man or a woman. I would like to get to a place in my life where I could dress up and be feminine, but I still feel quite insecure about what makes a man and how a man should act. But I feel like I'm getting there. When I was younger I was so free in what I was able to do.

Anthony: That freedom you experienced when you were younger, why do you think that began to change?

Alex: It's the world's perception of masculinity and femininity I suppose. I feel like there was more pressure on me when I came out as trans to act really masculine and not be feminine at all, or else people would think I wasn't being honest or something. Just stupid thoughts like that.

Anthony: When did you come out as trans?

Alex: November 2015. I’d just turned fifteen.

Anthony: How was that process for you?

Alex: I knew about six months before I told my mum in November. Before then, I'd been on the internet and I saw a picture of someone pre top surgery and after they'd had top surgery. And I just thought to myself, I'd like to get that, because I was very insecure about my chest… But before I realised that I was like that, a man, trans, I came out as genderqueer because I knew I wasn't a girl. It felt like a kind of bridge towards coming out as a trans man…I feel like if I'd been born cis, a cis man, I wouldn't have the open mind that I have. Because growing up as a girl and then finding this whole community, I feel like it's opened my mind more than it would have done if I hadn't gone through this whole experience. And it's something that I'm proud of.

Noah

Noah from In Conversation by Anthony Luvera.

Anthony: Is there a difference between being masculine and being a man?

Noah: I've taken so long to figure out who I am… There was this very macho idea amongst all the trans guys around the time of my first transitioning, ten years ago. They were all like, you have to walk a certain way, you have to stand a certain way, you have to nod to somebody a certain way… and you have to like football. And if you like anything different, nobody's gonna ever believe you're a man. And that was really, really toxic for me… they're the traditionally masculine traits which I just didn't have, but I’m still a man… Society – and the trans community – can be filled with toxic masculinity, enforcing this idea that people won’t see you as a man if you don't force yourself into being a kind of Desperate Dan from the Beano comics.

Anthony: When were you first able to articulate to yourself, your own masculinity?

Noah: I was always a tomboy. I would rather be with the boys than girls. I’d pick up on stuff and get told I was masculine, “she always thinks she's one of the boys”… I was doing it because I was seeing how boys were socialised and I knew I wasn’t a girl. I can remember knowing I was a boy, but not knowing how to articulate this… being six or seven and feeling it in myself… I just knew I was supposed to be with the boys.

Anthony: How did it go when you told your family?

Noah: I thought I'd lost my mum. She reacted really, really badly. It took about three years for her to come around. Now she loves me as her son… I realise it's a transition for her as well… I had my entire life knowing something was wrong and having that light bulb moment. Whereas for her, she was seeing her masculine daughter she thought was a butch lesbian, finally going, “actually I’m a man”, and she’s had to make peace with that. Now she's realised I'm exactly the same person… It is a transition for her as well, it's not just about me.

Anthony: The name you were once known as, what's your relationship like to that now?

Noah: It's always the first bloody question, “what was your name before?’ And my response is; ‘Do you intend on calling me it? Why do you want to know?”… They won’t admit it’s because they want to think of you as that person.

Anthony: I recently heard the term ‘dead name’. Can you tell me your thoughts about this?

Noah: I hate the term. It feels like misgendering to me. I say birth name… I think the phrase “dead name” just encourages the idea that you change as a person… from the day you’re born until the day you realise you're trans and come out, all of those experiences are important because they shape who you are. They shape your feelings on love, they shape your feelings on family, they shape your feelings on friendship, they shape your feelings on what’s morally right and what’s morally wrong... And they’re all just as important after you transition.

“Dead name”, to me, just feels so insulting. I’m still proud of who that person was… It would do her an injustice to say she never existed… the person I was before I transitioned made me the person I am today.

Josh

Josh from In Conversation by Anthony Luvera.

Anthony: Tell me a bit about what's in the picture?

Josh: Family number 26 in the competition. I can't remember whether we won or not, we used to enter everything. That's part of being at Butlins, isn't it? But what's interesting is the battle mum would have had with me, to have my hair all brushed and wearing the little socks and this dress… I hated having long hair and I hated wearing dresses and it used to be a constant battle… You’ve just seen the surface you've not actually seen me… that is not actually a representation of me at that age at all.

Anthony: What age were you when you were able to articulate your gender identity?

Josh: I held off my transition for about seven years longer than I would have liked. I didn’t transition until my thirties… I first spoke to a doctor about it when I was about 24. But there wasn't any information. They didn't have leaflets or things like that, or anything really, and the doctor didn't really know what to do… I was referred to a psychologist. It was mainly to say that you were sane.

I do think gender is very much a construction. You know, even in academia the concept of masculinity is different than down the working men's pub. And it's different in different countries. So how you perform masculinity, how you live your life as a man, is a social construct. It's society. If you step out of society's ideas on what maleness is or what masculinity is, then you're punished, and people try and school you and police you back to it. These concepts about what is masculine in all our different societies, they're all false…

Anthony: Can you tell me a bit about what the markers of masculinity are for you?

Josh: I don’t know. It’s really hard to describe to people how you know you’re a man when those ways of describing masculinity to me aren’t true. You need to find your own. It's not so much about my body sounding and looking right… when I initially transitioned, what was fascinating was, as I started to be read as male, was the level in which people… give you that male privilege.

Anthony: How do people give you male privilege?

Josh: People listen to you in meetings, definitely. Having experienced sexism and living life in a female body in the world, it's been quite fascinating because there is a difference between the way men and women are treated. No matter what level within the scale of male privilege you are. And often women will give you the power – Don't! Why are you giving me that? And men would give me a different respect. And then you want to say – Why? I'm saying exactly the same things! …

I think the biggest thing is, people have read me more as male as I've got older… But actually, what they are seeing is a very whole human as opposed to that’s a man.

Ed

Ed from In Conversation by Anthony Luvera.

Anthony: Masculinity… I wonder what your thoughts are about the word?

Ed: When you transition you look for role models and you see such a wide variety of men being men. There are also generational things, like holding a door open for a lady. I've always done that because, why close the door in their face? Once I transitioned, I periodically get abuse from women for doing that, for being patronising. But when they perceived me as a woman there was no issue. Also, people trying to mould you into their view of what a man should be – when you should wear a tie, the way you should walk, the way you should sit, the way you should speak, words you should use and shouldn't use. I've always said, ‘Are you all right love?’ And when I was perceived as female that was fine, as male I'm told I'm being sexist. Masculinity is whatever being male is to you, because if you take a true look around there are such a wide variety of men.

Anthony: When were you first able to identify that you felt masculine?

Ed: I am still the same person. It's the body changes that have made the difference. I'm seeing on my body what should be there – having a beard, having a masculine chest. I wear a packer because I have had people attempt to find out if there's anything down there, which is quite amusing when you're not used to that sort of thing! I suppose feeling masculine is in your reaction to people's reaction to you. I would say 99.9% of how I behave is exactly the same as I behaved or dressed before transition… Looking in the mirror, I identify with what I see back and identify that as male.

Anthony: Does your reflection feel more like you now than it ever did before?

Ed: Yes… Being identified as male in the world is interesting because it also changes in a group discussion, people will listen, or if you go to speak, people will stop… rather than when you're identified as female, when it's kind of, ‘Shut up dear’. I suppose when you experience people listening to what you have to say or stopping speaking to hear what you've got to say then you know you're in the male world.

Anthony: When were you first able to identify within yourself, your gender identity?

Ed: The first time I knew it was something was at junior school… knowing I should be going into the boys toilets and being told no, and not understanding why. I think that's the time I realised what was going on in my head wasn't normal.

Anthony: Is masculinity a behaviour or an innate quality?

Ed: I think it's a mixture of things. I think there's socialisation, how people are brought up to be masculine or feminine, and an element of who the person is naturally. Going off slightly, the first time I went swimming after top surgery I was nearly sick at the door of the pool. I was terrified I was going onto the poolside half-naked and would be arrested because I had been brought up to think the chest needs to be covered.. just having to come to terms with fighting that socialisation of how men dress for a swimming pool and how women dress for a swimming pool… the gossip is different in the changing rooms, between the mens and womens, but I'm sorry, it is still gossip!

Oliver

Oliver from In Conversation by Anthony Luvera.

Anthony: Tell me about the photographs you’ve brought.

Oliver: Mostly I picked out ones from when I was a toddler. Because looking at them, I look quite androgynous. I don't like looking too girly in photographs. It feels too much of a disconnect and I don't really like that feeling. I do like to relate back to my old pictures like most other people. But it feels a bit sad if I can't identify with how I used to be, the way other people can...

Anthony: When did you begin to accept your trans identity?

Oliver: Probably about 15, but I knew before then definitely. I just wasn't sure exactly what it was. When I did find out about trans people, and I knew that was me, it did take a while to come to terms with it and tell others… I think I'd been confused before then, but by that time I knew it was more than just confidence issues or anything like that. By about 12 I knew I wasn’t a girl…

Anthony: The word ‘transition’ is often associated with the journey of a trans person. Can you tell me about that journey for you?

Oliver: I think a lot of it is accepting yourself. Well, for me it was anyway. It obviously includes physical transition, which I've been doing the past couple years. And that's really helped me with sorting my self-confidence and feeling my authentic self. But a lot of it is social as well. I think getting acceptance is really important from people that are important to you.

Anthony: Can you say a little more about feeling your authentic masculine self?

Oliver: At first it was quite difficult because I was either perceived as a queer girl or woman, and then at other times, a very in-between person. That was a time I found quite hard because I didn't know how I was going to be perceived when I went out. I didn't know if people were gonna think I was a girl or a boy. If they didn't know then you’d get funny looks, and then name-calling, and other not nice stuff from strangers, just because they don't really understand what they're seeing… When I presented more masculine, I was a lot more accepted… I guess a lot of people would think I was cisgender. That's been more the case recently as I have physically transitioned and started with hormones. It does happen every now and again that someone clocks me, doesn't think something's quite right, and takes it upon themselves to question who I am. Even though I have no idea who they are.

Anthony: Tell me about the process of physical transition you're undergoing.

Oliver: I've been on hormones, testosterone, for about 14 months now. And in about two weeks I'll be getting top surgery, which is a really big step for me. It's something I've wanted for a very long time. It's really exciting. It feels quite unreal sometimes. I've been waiting for so long, this next step.

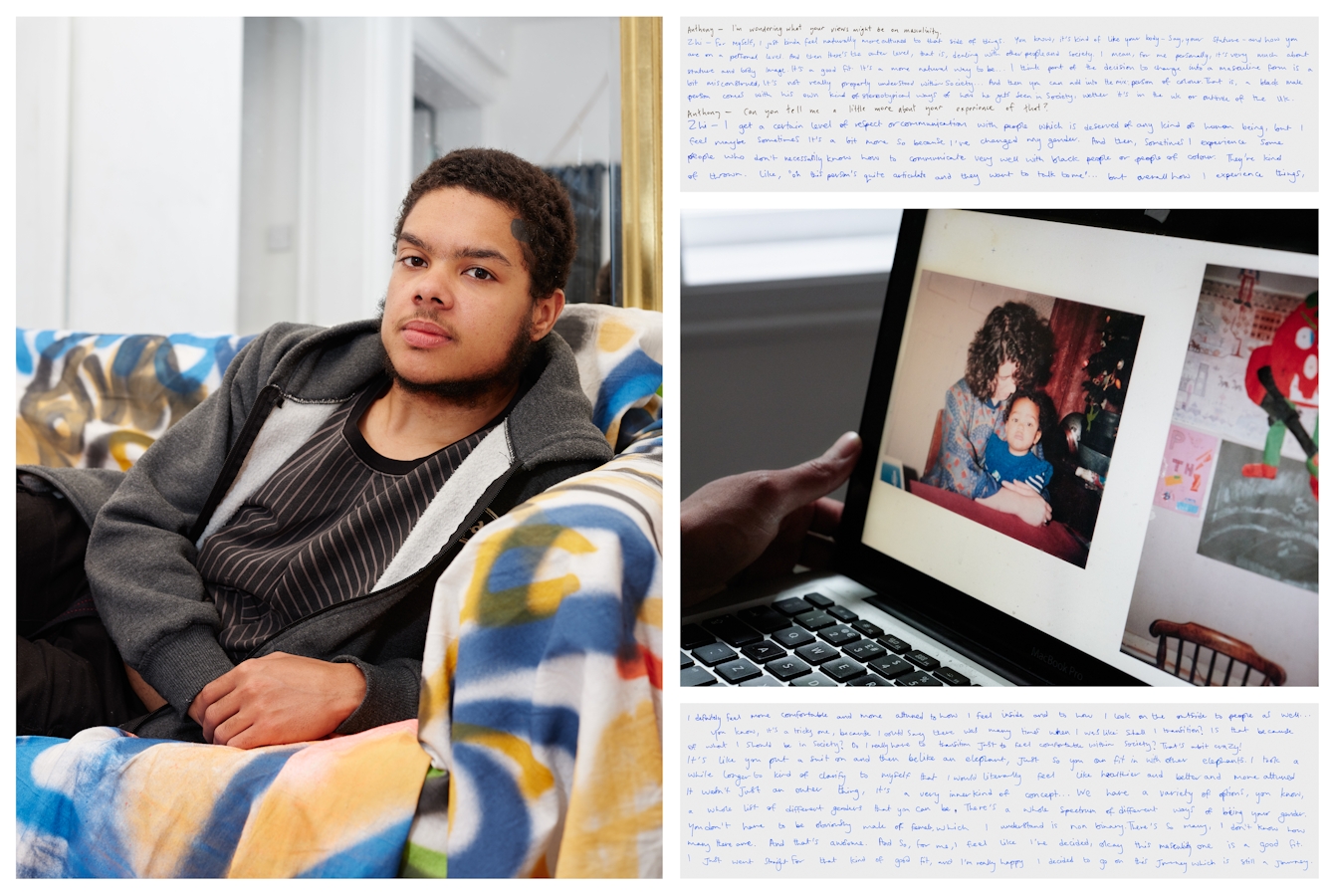

Zhi

Zhi from In Conversation by Anthony Luvera.

Anthony: I'm wondering what your views might be on masculinity?

Zhi: For myself, I just feel kinda naturally more attuned to that side of things. You know, it's kind of like your body – say, your stature – and how you are on a personal level. And then there's the outer level, that is, dealing with other people and society. I mean, for me personally, it's very much about stature and body image. It's a good fit. It's a more natural way to be...

I think part of the decision to change into a masculine form is a bit misconstrued, it's not really properly understood within society… And then you can add into the mix: person of colour. That is, a black male person comes with his own kind of stereotypical ways of how he gets seen in society, whether it's in the UK or outside of the UK.

Anthony: Can you tell me a little more about your experience of that?

Zhi: I get a certain level of respect or communication with people which is deserved of any kind of human being, but I feel maybe sometimes it's a bit more so because I've changed my gender. And then, sometimes I experience some people who don't necessarily know how to communicate very well with black people or people of colour. They're kind of thrown. Like, “Oh this person's quite articulate and they want to talk to me”… but overall how I experience things, in myself, I definitely feel more comfortable and more attuned to how I feel inside and to how I look on the outside to people as well…

You know, it's a tricky one, because I could say there was many times when I was like: Shall I transition? Is that just because of what I should be in society? Do I really have to transition just to feel comfortable within society? That's a bit crazy! It's like you put a suit on and then be like an elephant, just so you can fit in with other elephants. I took a while longer to kind of clarify to myself that I would literally feel like healthier and better and more attuned with myself. It wasn't just an outer thing, it’s a very inner kind of concept…

We have a variety of options, you know, a whole list of different genders that you can be. There's a whole spectrum of different ways of being your gender. You don't have to be obviously male or female, which I understand is non binary. There’s so many, I don’t know how many there are. And that's awesome. And so, for me, I feel like I've decided, okay this masculinity one is a good fit. I just went straight for that kind of good fit, and I’m really happy I decided to go on this journey which is still a journey.

About the artist

Anthony Luvera

Anthony Luvera is a socially-engaged artist, writer and educator. The long-term collaborative projects he creates have been exhibited widely in public spaces including Tate Liverpool, London Underground’s Art on the Underground, British Museum and National Portrait Gallery and many other venues around the world. Anthony is Associate Professor of Photography at Coventry University. He also designs and facilitates public education programmes and community photography projects across the UK.