Some of us may remember hard toilet paper and shudder a little as we recall the shiny, smooth sheets. But there was a time when Brits proved difficult to convince of the benefits of soft toilet tissue.

How Brits went soft on toilet paper

Words by Alice White

- In pictures

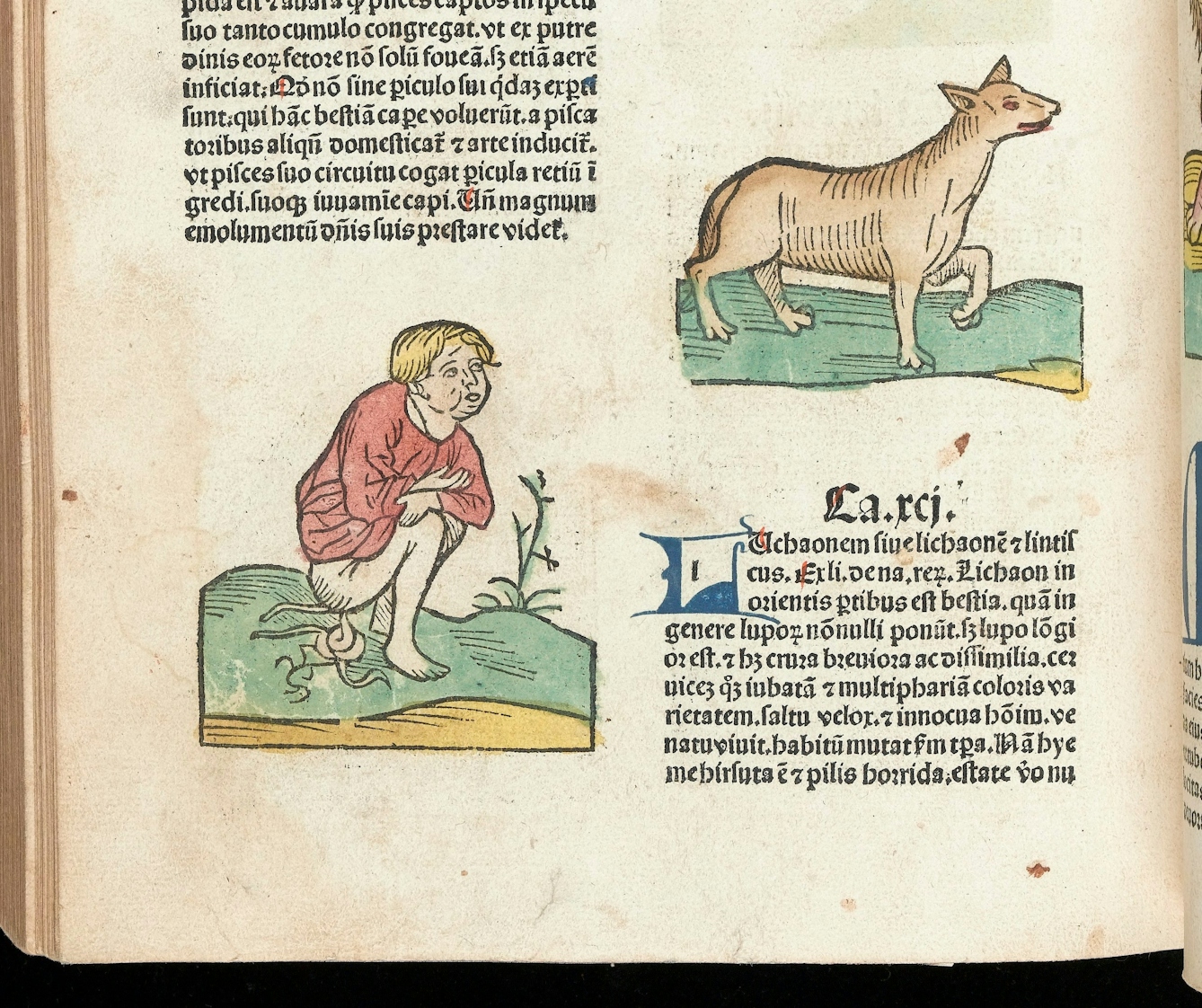

For most of human history, there was no single specific product to use for wiping. We simply used whatever natural resources were to hand.

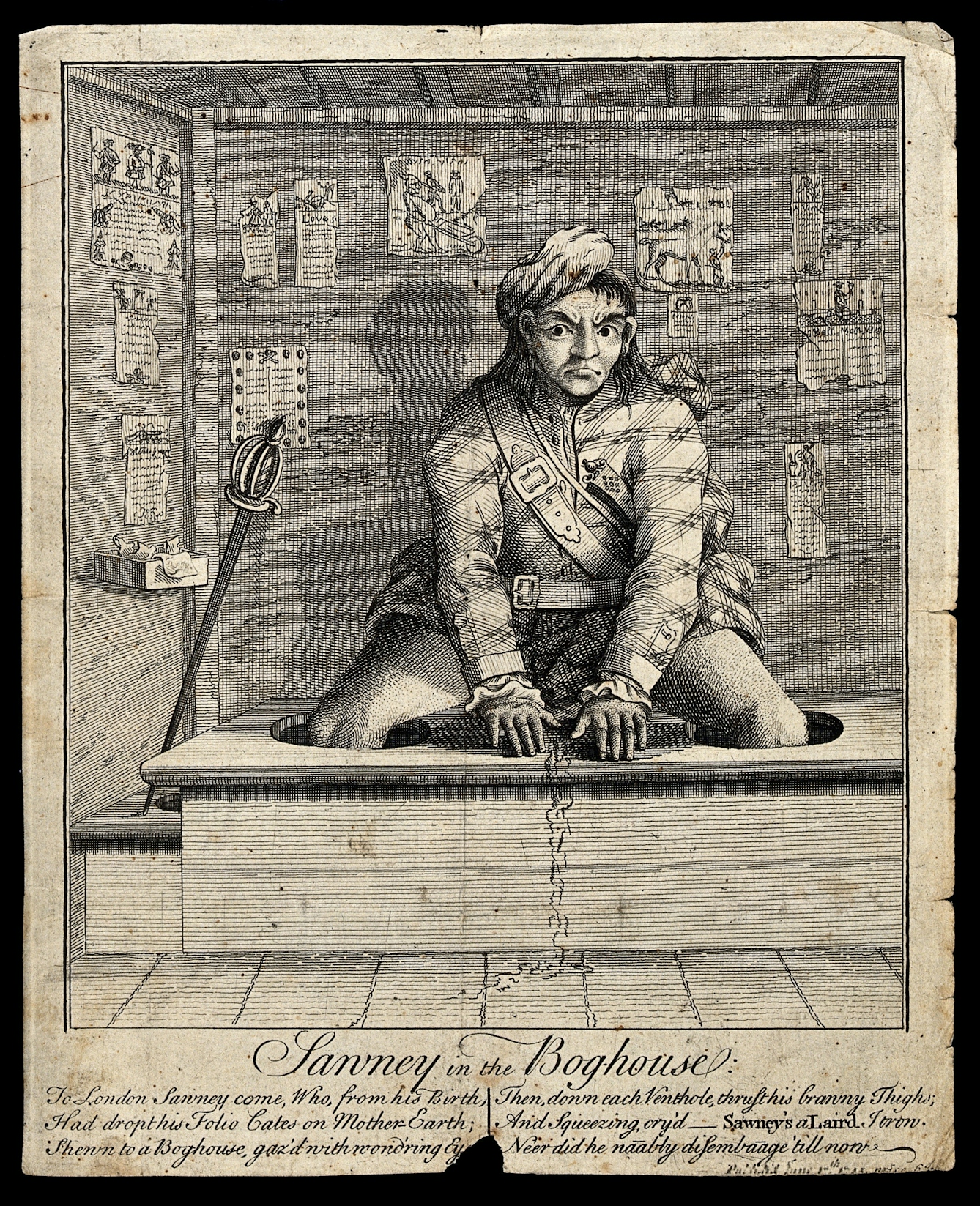

Eighteenth-century British people used paper to wipe, as shown on a shelf beside the toilet in this caricature mocking a Scottish man for his ignorance of “civilised” facilities. This paper wasn’t toilet paper as we know it, though: people simply recycled newspapers and the pages from cheap books.

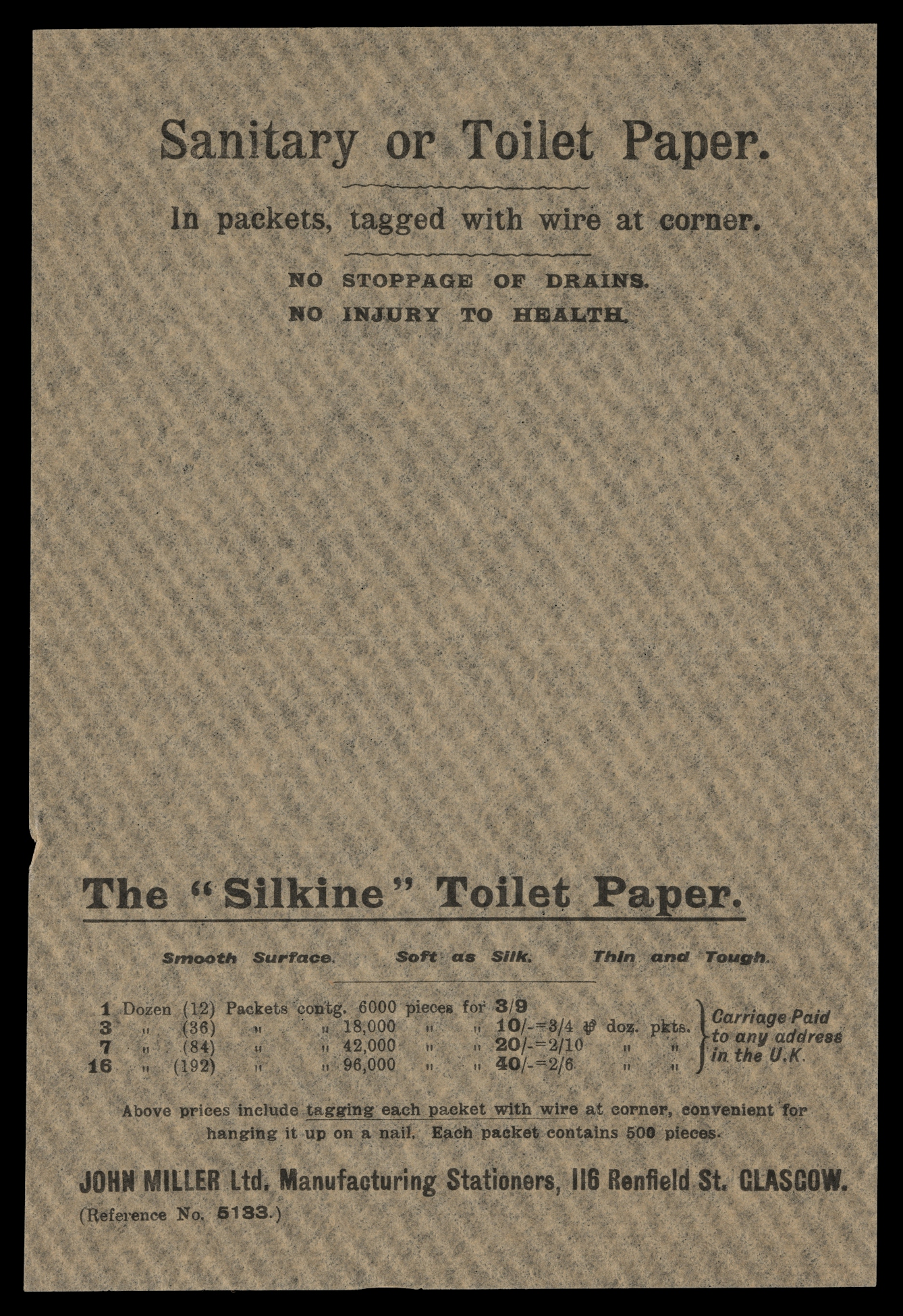

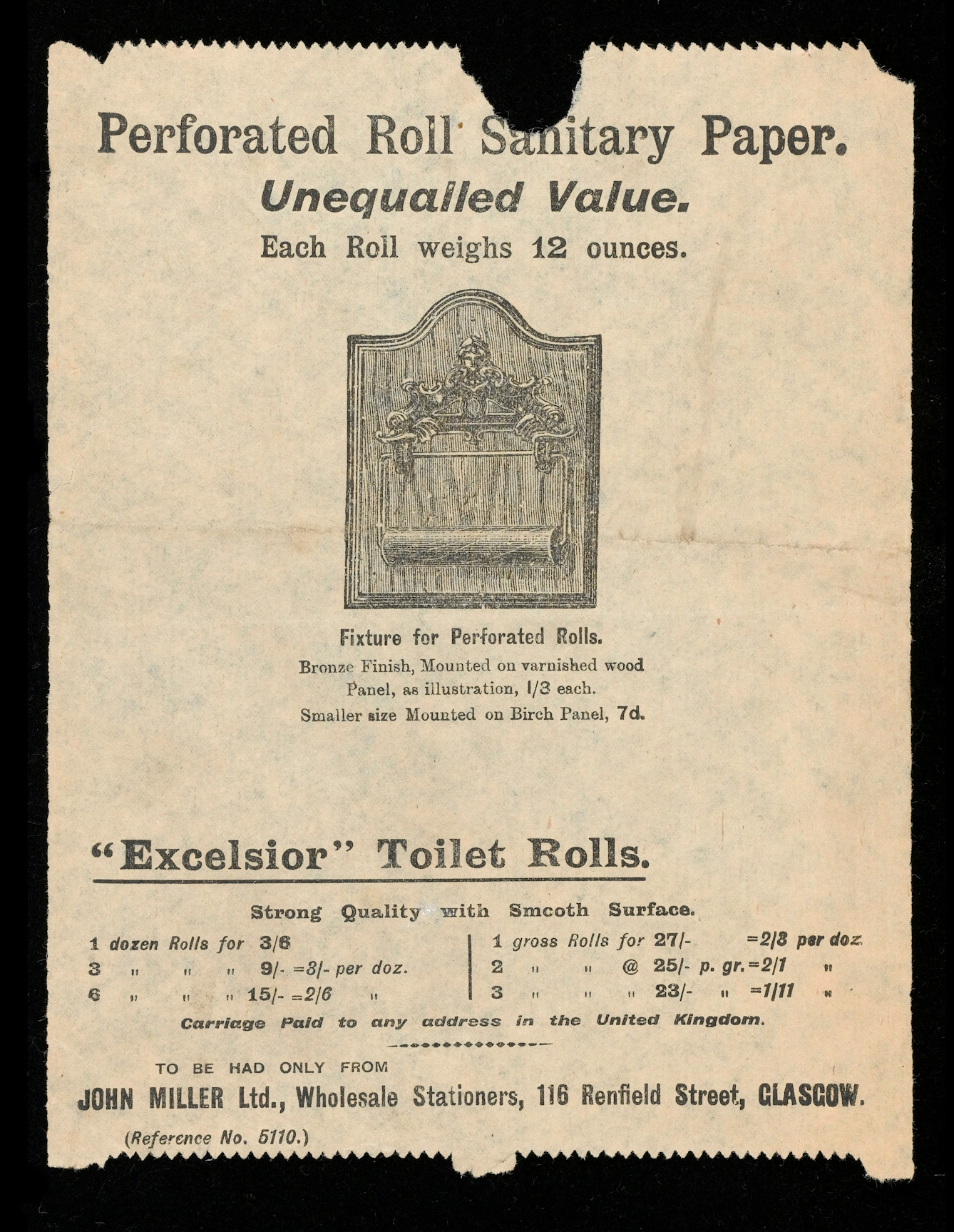

By the Victorian era, you could purchase specially manufactured toilet paper, often with wire at the corner, or in a box so that one sheet could be pulled out at a time. John Miller Ltd sold paper including Purolette and Silkine, which promised no “injury to health”. What could that mean? Well, other brands were advertised as “splinter-free”, which may explain things (and give you nightmares)!

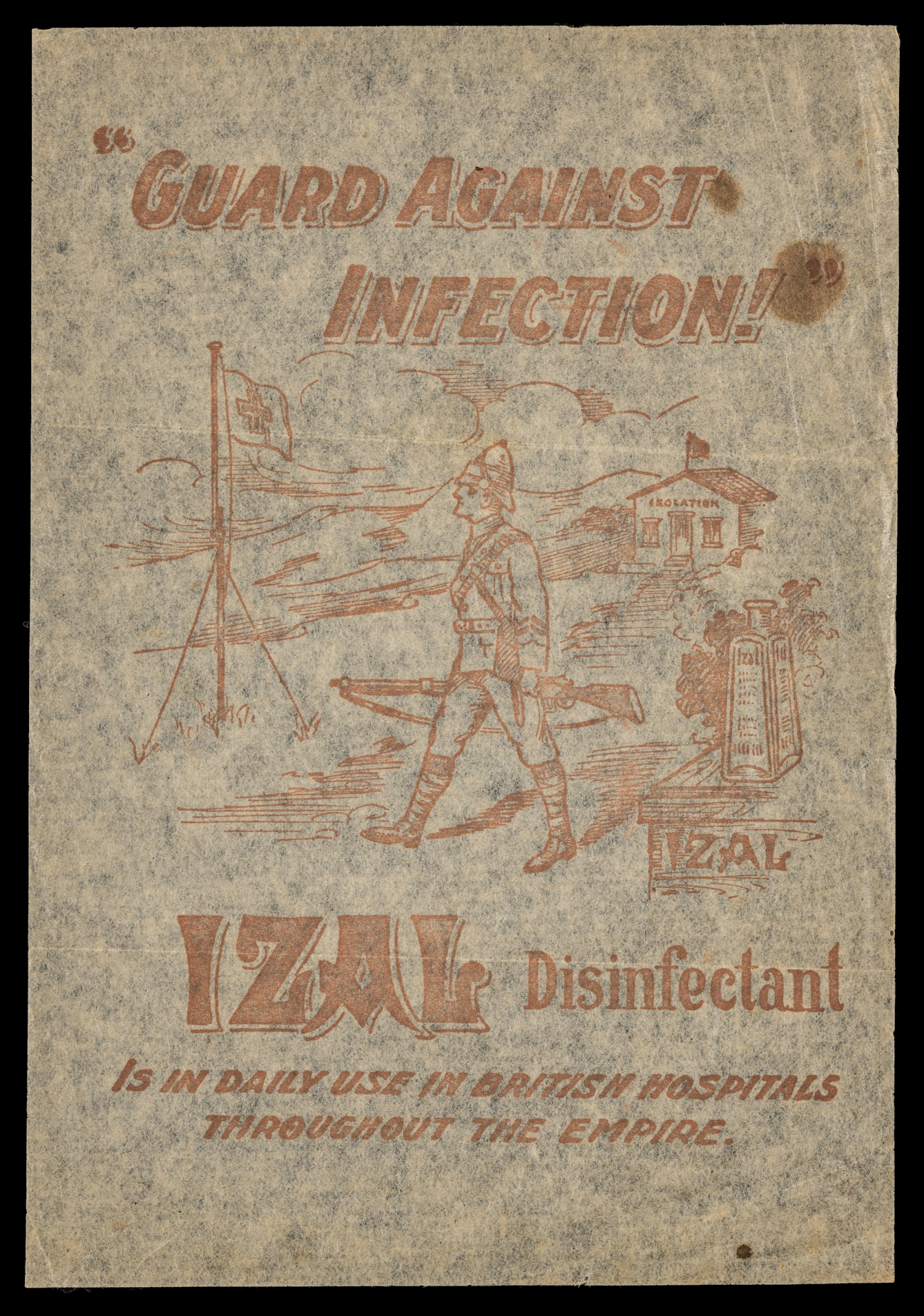

Newton, Chambers & Co. manufactured Izal, one of the best-known toilet papers in Britain. Izal was hard and ‘medicated’ with disinfectant. Our archives show that in 1956, the company asked the psychologists of the Tavistock Institute to do some consumer research into whether they should begin manufacturing a new line: were British people ready for soft, unmedicated toilet tissue?

More than 400 interviews later, the psychologists reported back. The market was “softening up”, but faster in some places than others. In Glasgow, the psychologists said, many people still used newspaper. In Yorkshire, “‘soft’ papers were viewed with great distrust and anxiety because they were not ‘reliable’”. Any new paper would have to be marketed as strong and good value for money to win over these customers. And people were reluctant to change their bathroom fittings, so free roll-holders might be a good incentive to change.

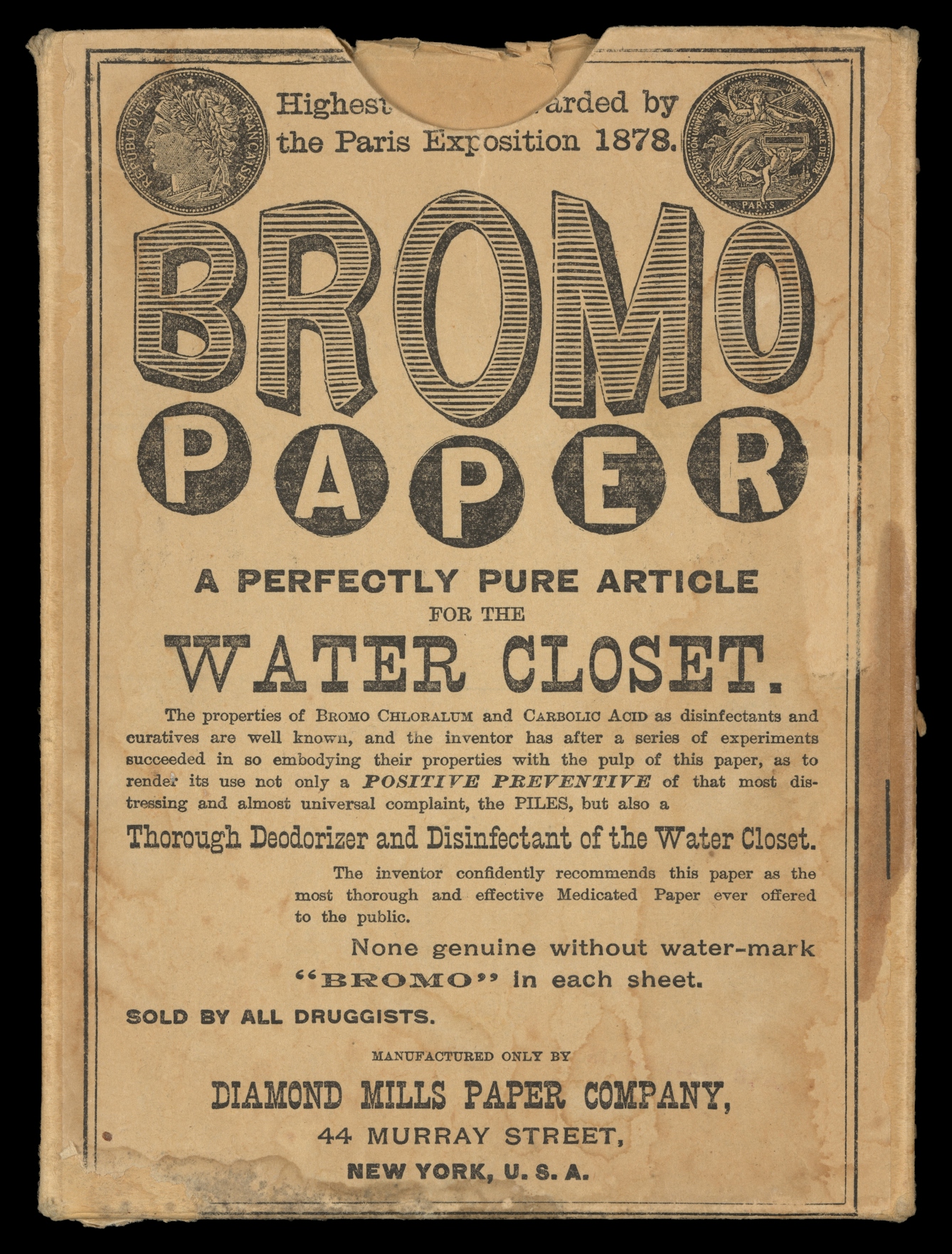

In London, Birmingham and Manchester, women and young couples were making the move to soft paper. Men were more accustomed to “rubbing or scraping” and would need to be trained to use soft paper without dirtying their hands. As for medication, people “turn their noses up at Izal (literally, almost, since for them the smell of the medication is one of the things which degrades it)”. Bromo was a strong competitor in the ‘hard’ category, and Andrex was “becoming synonymous with ‘soft’”, so Izal needed to act fast if they were to get in on the game...

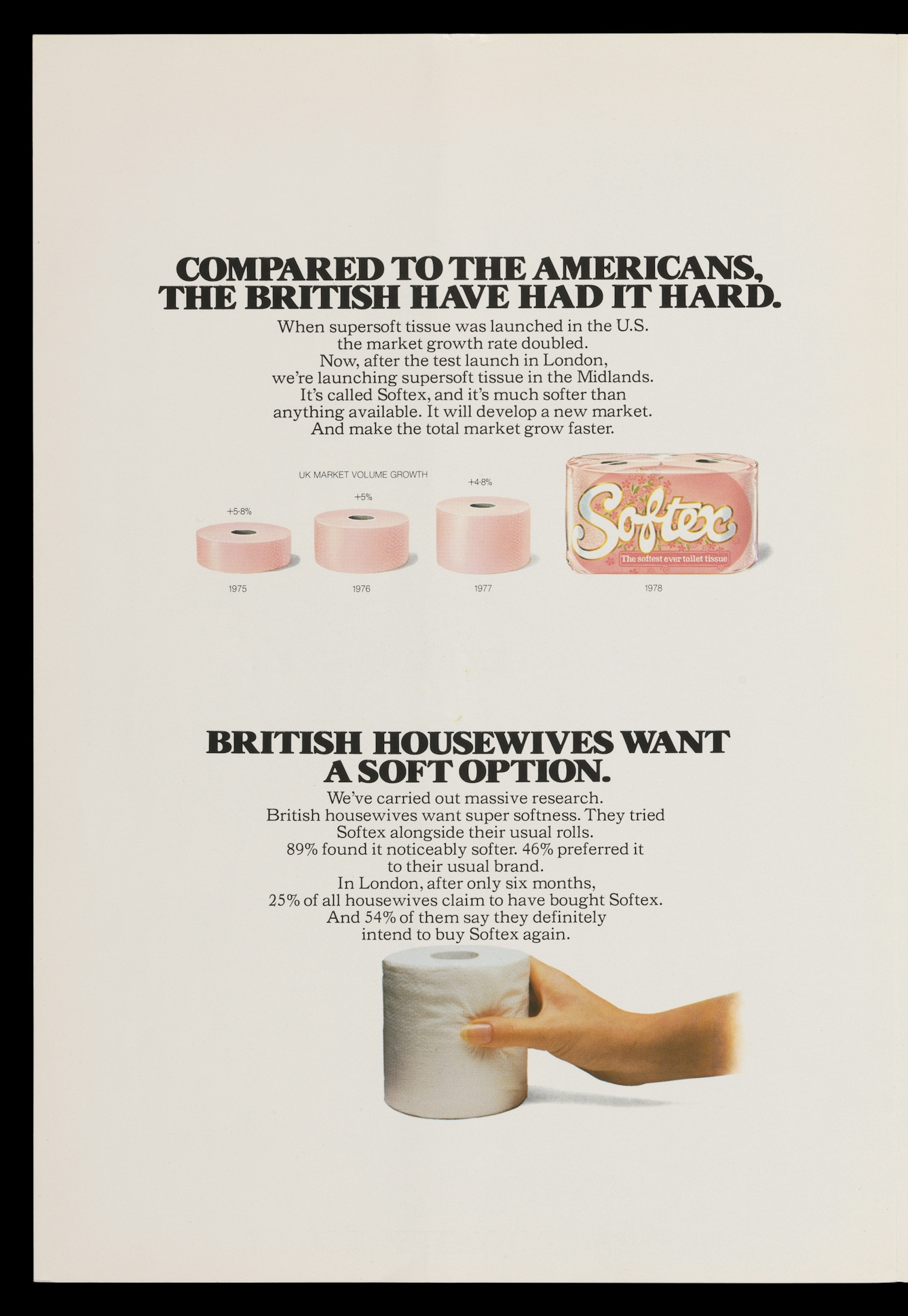

...but speedy change was not to be in the British toilet-paper stakes (Americans liked soft paper, but the psychologists recorded that Brits thought Americans were “extravagant” and prone to “crazes” that would pass). So it was that in 1970, the British civil service were just beginning to consider whether they should adopt soft toilet tissue. Our archives tell the story.

The Directory of Supply had advised that the annual bill for loo paper would increase from £370,000 to £1 million in the switch to soft, so it would need to impress. Dr Daniel Thomson of the civil service Medical Adviser’s Office asked his friend Sir Graham Wilson of the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine to investigate whether this newfangled soft paper was up to the job.

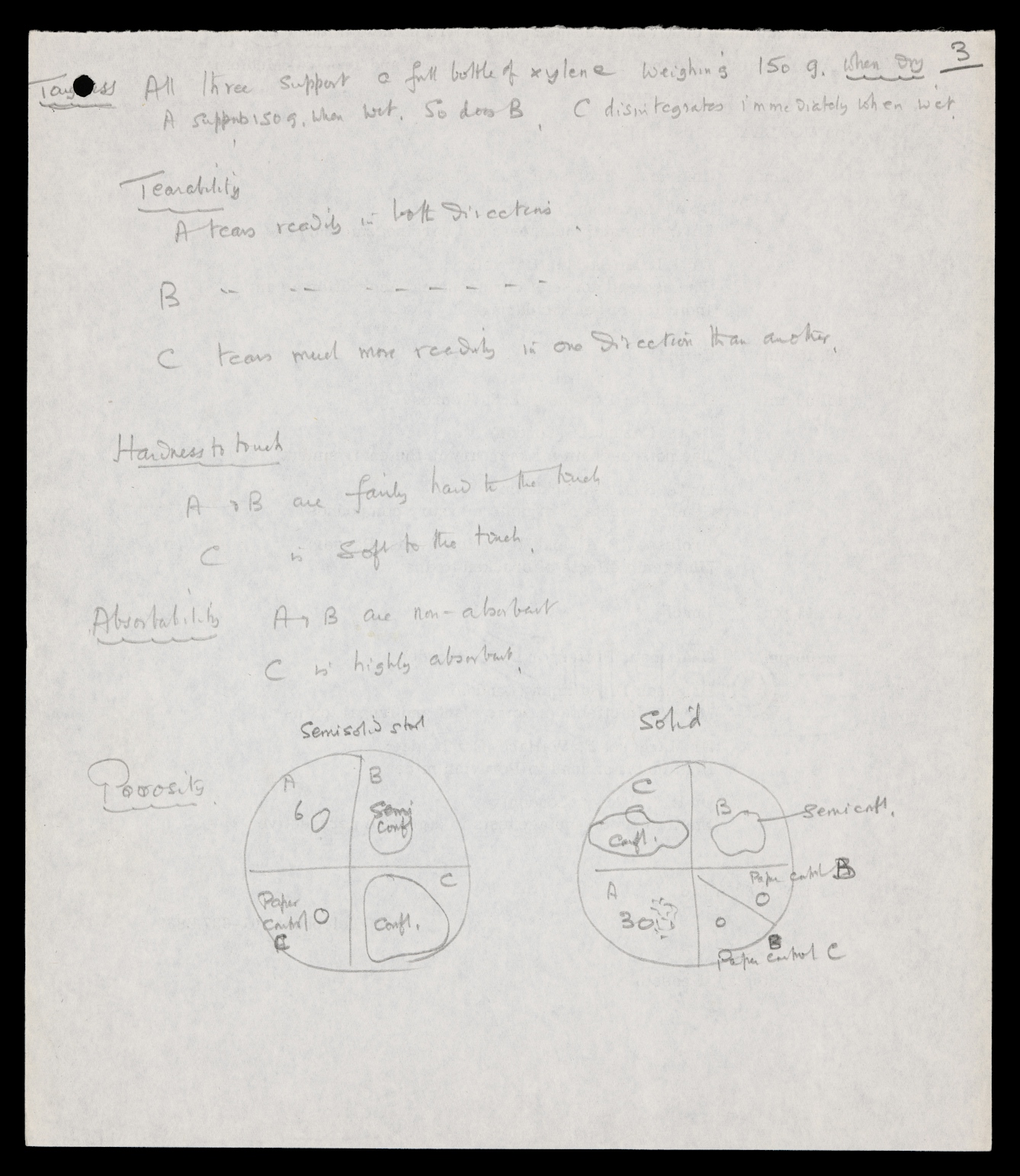

Wilson went to remarkable lengths to compare toilet papers. He studied them under the microscope, tested their absorbency (hard toilet paper takes two hours to absorb a drop of water!), and perhaps most crucially, he conducted a “porosity test”. He pressed the third finger of his right hand onto paper with a stool sample underneath, then pressed this onto a Petri dish. Would germs get through?

Wilson’s report to Thomson explained that with soft paper, people’s “fingers would be virtually in contact with the faecal material” and so “until the routine washing of hands after defecation becomes a universal practice”, soft toilet tissue simply posed too great a risk to health. This explains why many people today remember hard toilet paper from institutions like schools!

Though the civil service could not accept soft toilet paper, British householders did. As this trade advertisement shows, more and more people went over to soft toilet tissue. They also dabbled with other trends, such as rolls coloured to match their bathroom suites.

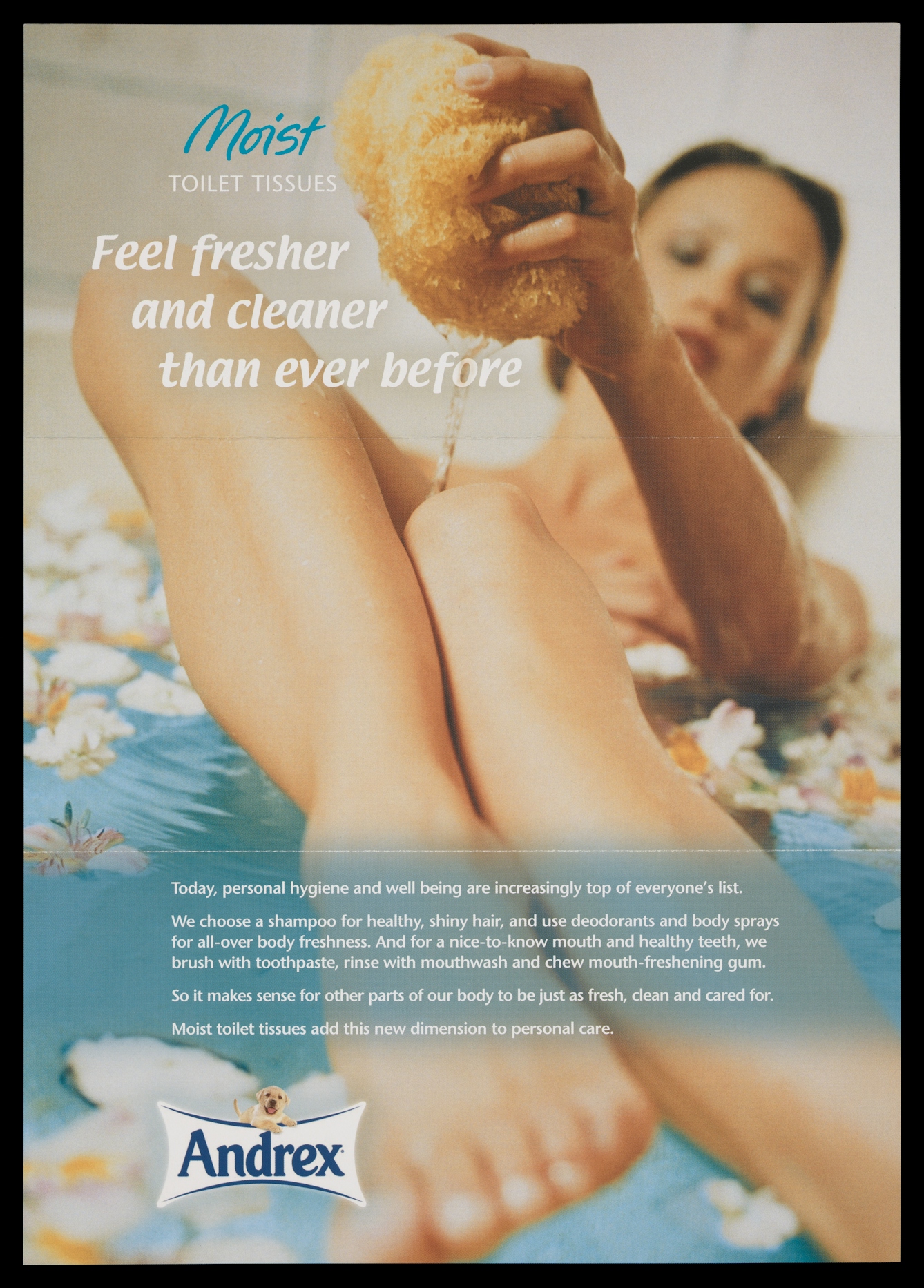

Today the echoes of the historic investigations are still around: the emphasis on soft and strong continues. New innovations such as moist tissues have come to market too, but fatbergs and environmental issues may put a damper on our use of these products. Perhaps the future will see us backing away from the reluctantly adopted toilet paper, and eyeing up the bidet instead.

About the author

Alice White

Alice is a digital editor and Wikimedian for Wellcome Collection. Before joining Wellcome, she researched frogs, moustaches, psychiatry in World War II, and British science-fiction fans.