As Covid-19 first swept the UK in March 2020, seven Nightingale field hospitals were rapidly constructed across the country. The design ideas behind these conversions of existing buildings can be traced back to principles set out by Florence Nightingale in the mid-19th century, which remain startlingly relevant today.

Florence Nightingale, Victorian design and the treatment of Covid-19

Words by Iria Suárez

- In pictures

Florence Nightingale (1820, Florence–1910, London) is well known for being the founder of modern nursing. However, she should also be considered the founder of modern hospital design, as she developed a leading set of principles for the layout of hospitals. Her forensic work ‘Notes on Hospitals’, first published in 1858, became one of the most influential guidelines on hospital construction, which today can be compared to those developed to create the Covid-19 field hospitals.

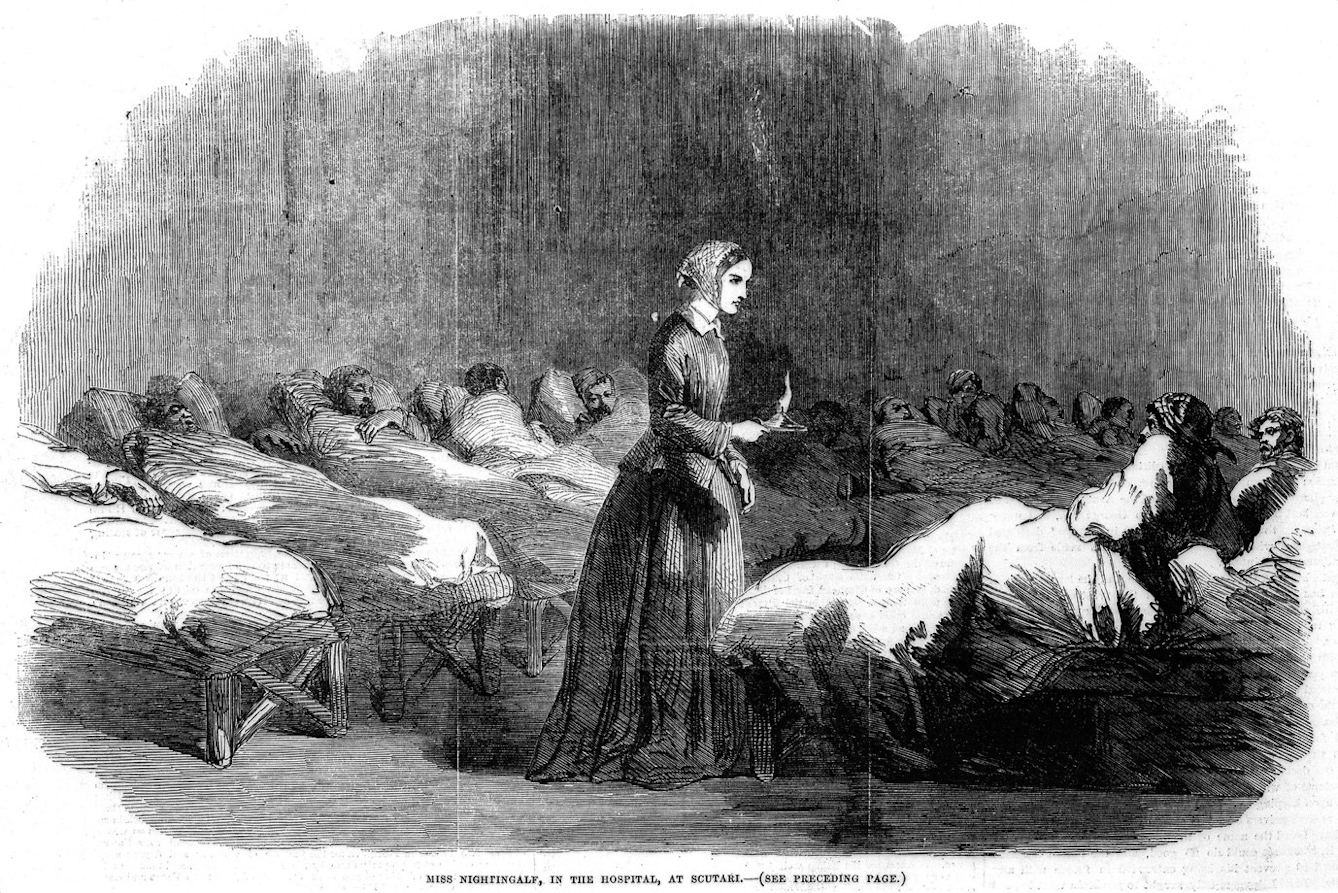

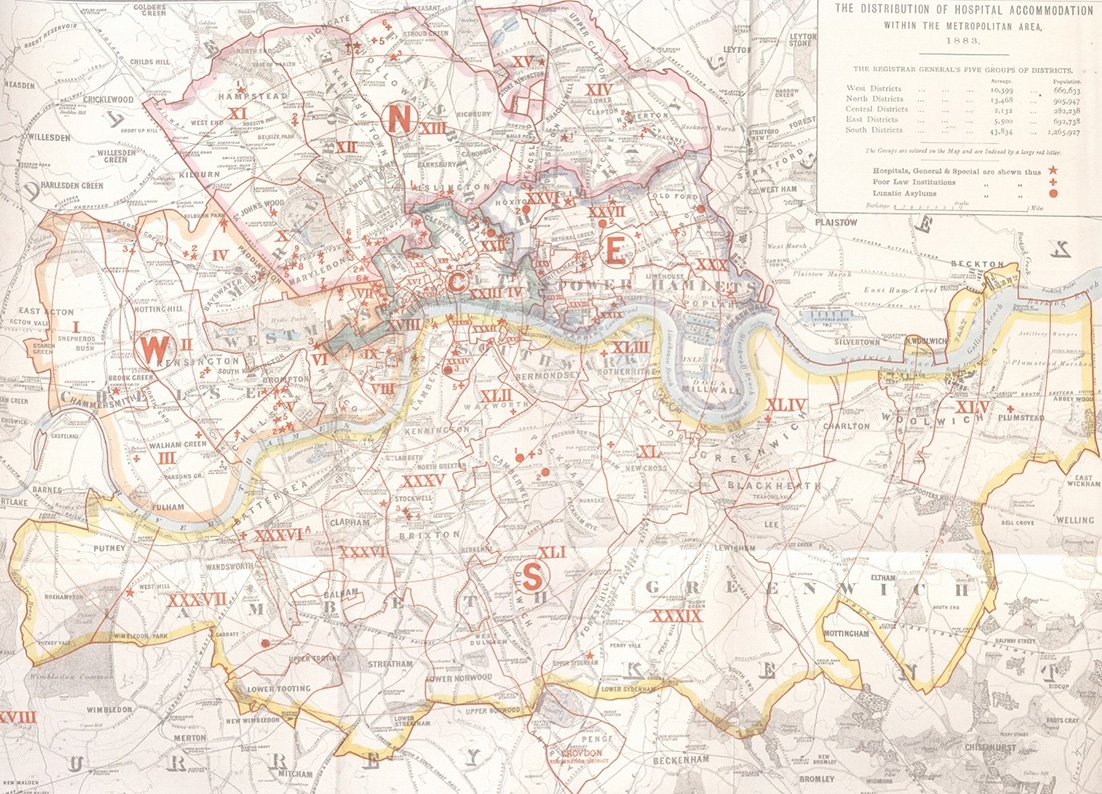

After her nursing experience in the British military hospital at Scutari, Turkey, during the Crimean War (1853–56) and meticulous observation of the needs of a hospital ward, Nightingale advocated for vital refinements in hospital buildings and fittings. The driving force behind her campaign was the striking statistics on mortality within hospitals, especially those serving large, crowded cities such as London, where the death rate was 91 per cent.

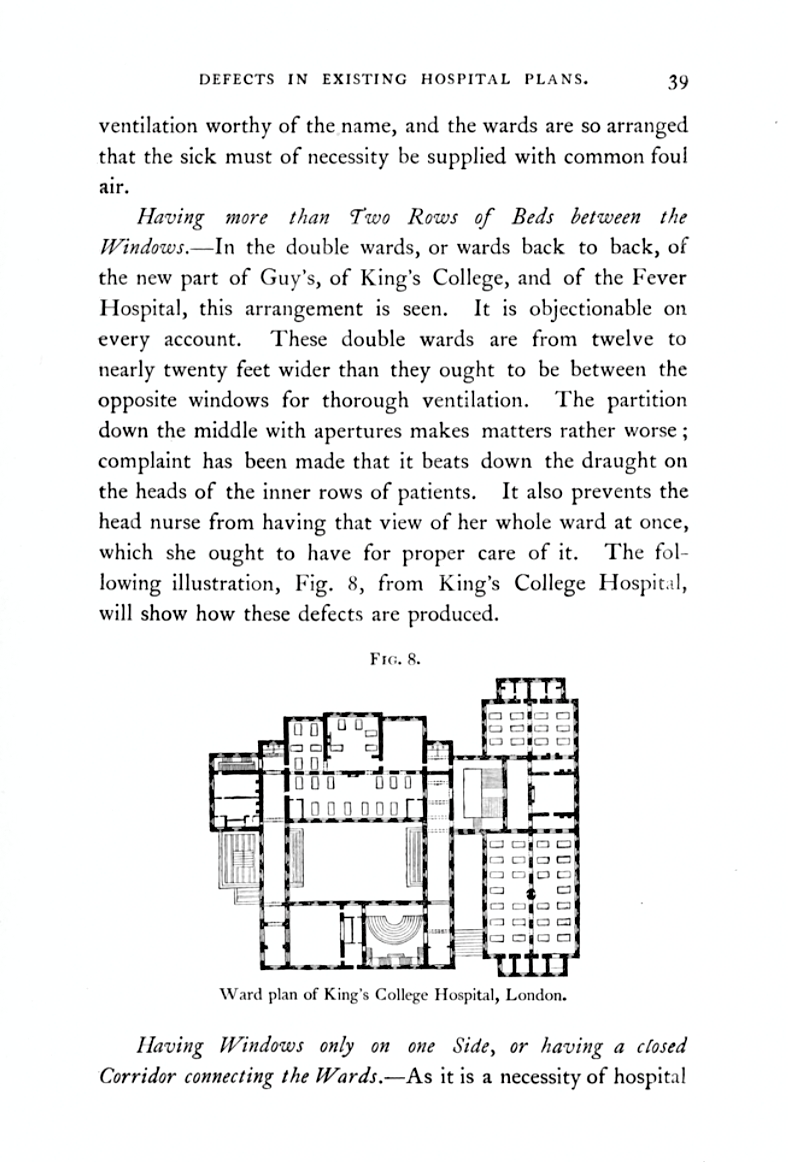

In ‘Notes on Hospitals’, Nightingale carried out a thorough examination of the design of existing hospitals, identifying their defects and proposing a new system of hospital design. Her specifications were determined by the contemporary belief in ‘miasmatic theory’, namely the damaging inhalation of gases derived from decomposed organic matter. At the time, miasmas were generally believed to be the cause of the infectious diseases threatening Europe.

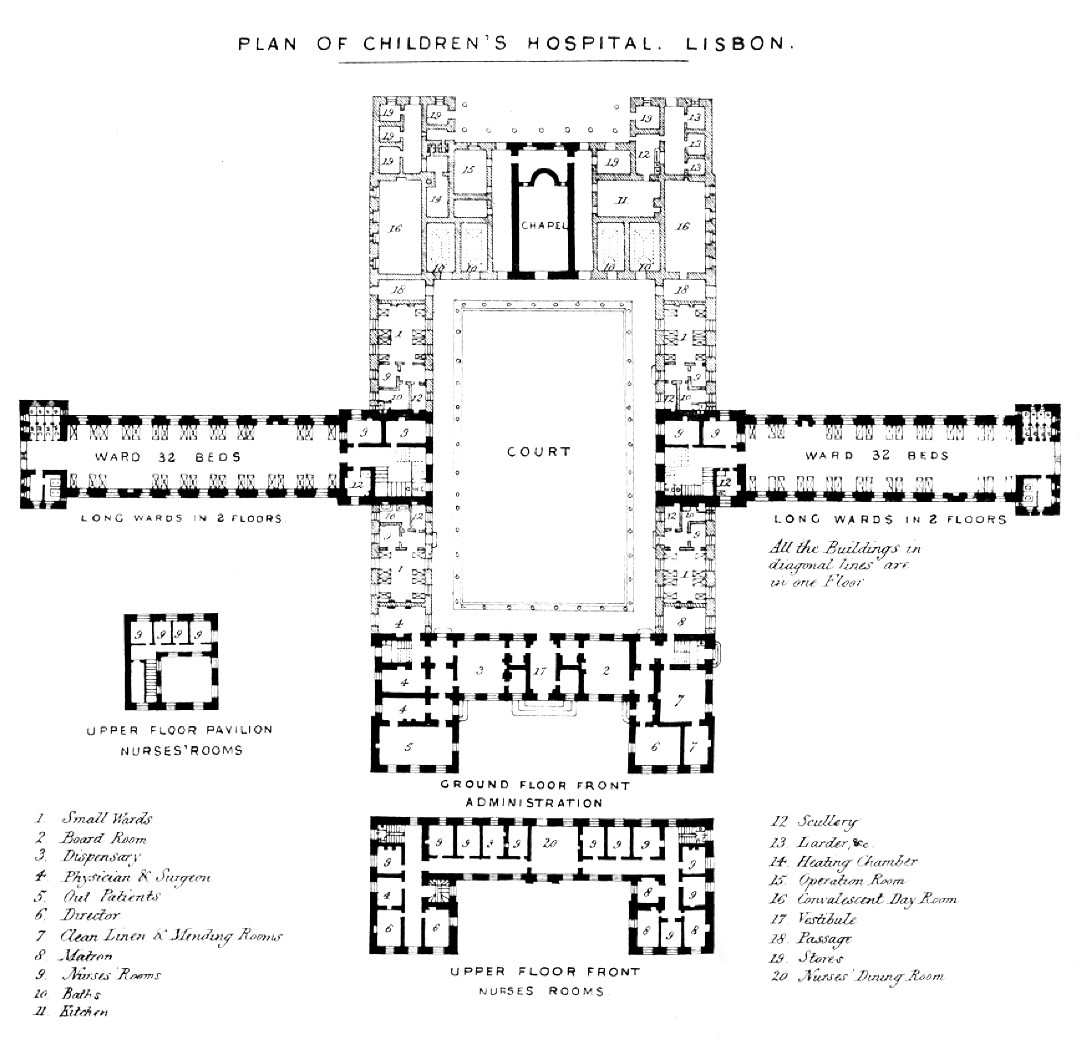

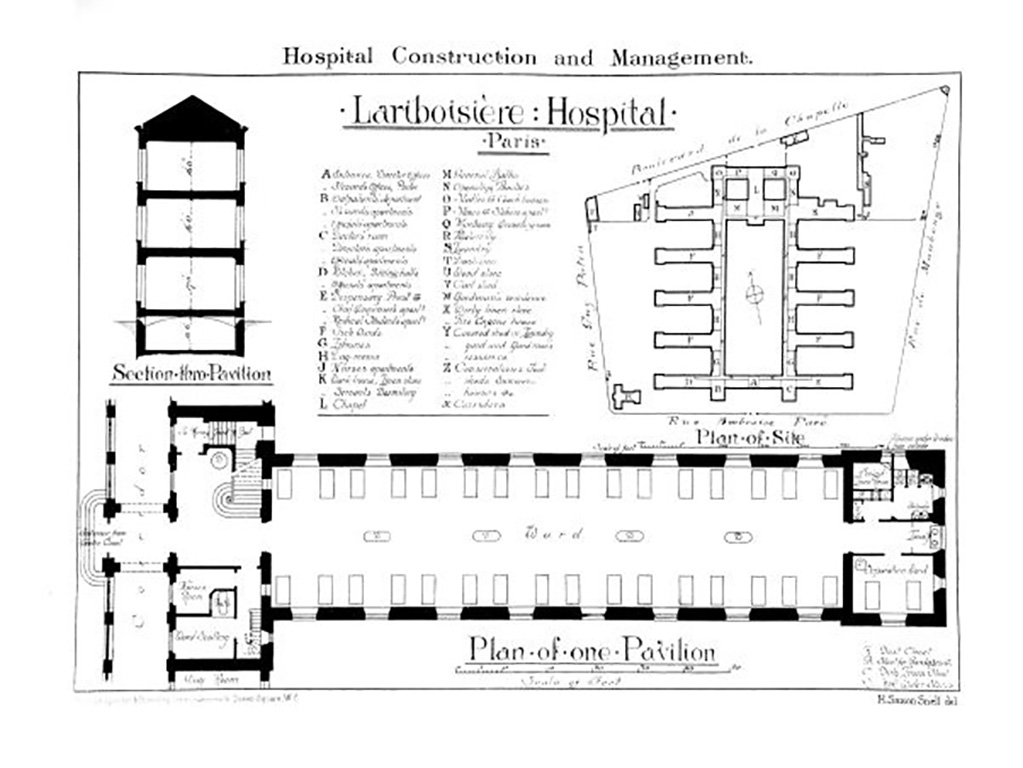

The new system of hospital design was specifically developed for ventilation, allowing the miasma to disperse. To achieve this, the principal premise of hospital construction was to place the sick in independent wards, also named pavilions. A pavilion was a rectangular space with a considerable number of windows to provide cross-ventilation of fresh air and light, as well as enabling supervision by the minimum number of nurses.

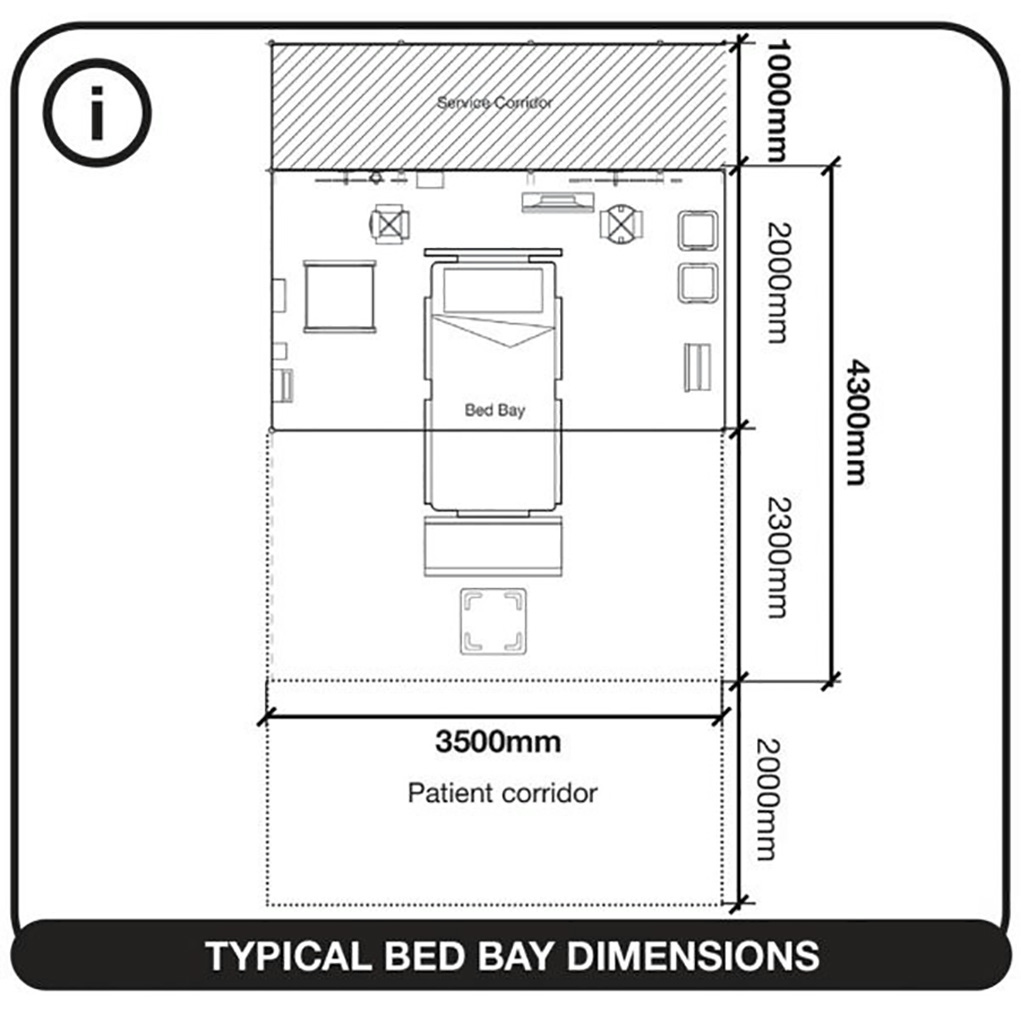

At the time, the archetype for hospital design, using the pavilion principle, was the Hôpital Lariboisière in Paris. This had two beds per window, an ample corridor in the middle, the nurse’s room at the beginning of the ward and toilets at the end. Inspired by this, Nightingale carefully stipulated the materials and proportions of the pavilion. In particular, she specified between 20 and 32 patients, and that each patient should have a minimum bed space of 100 square feet (9.3 square metres). These proportions allowed a sufficient amount of airflow, free movement of three persons, and the use of a portable bath.

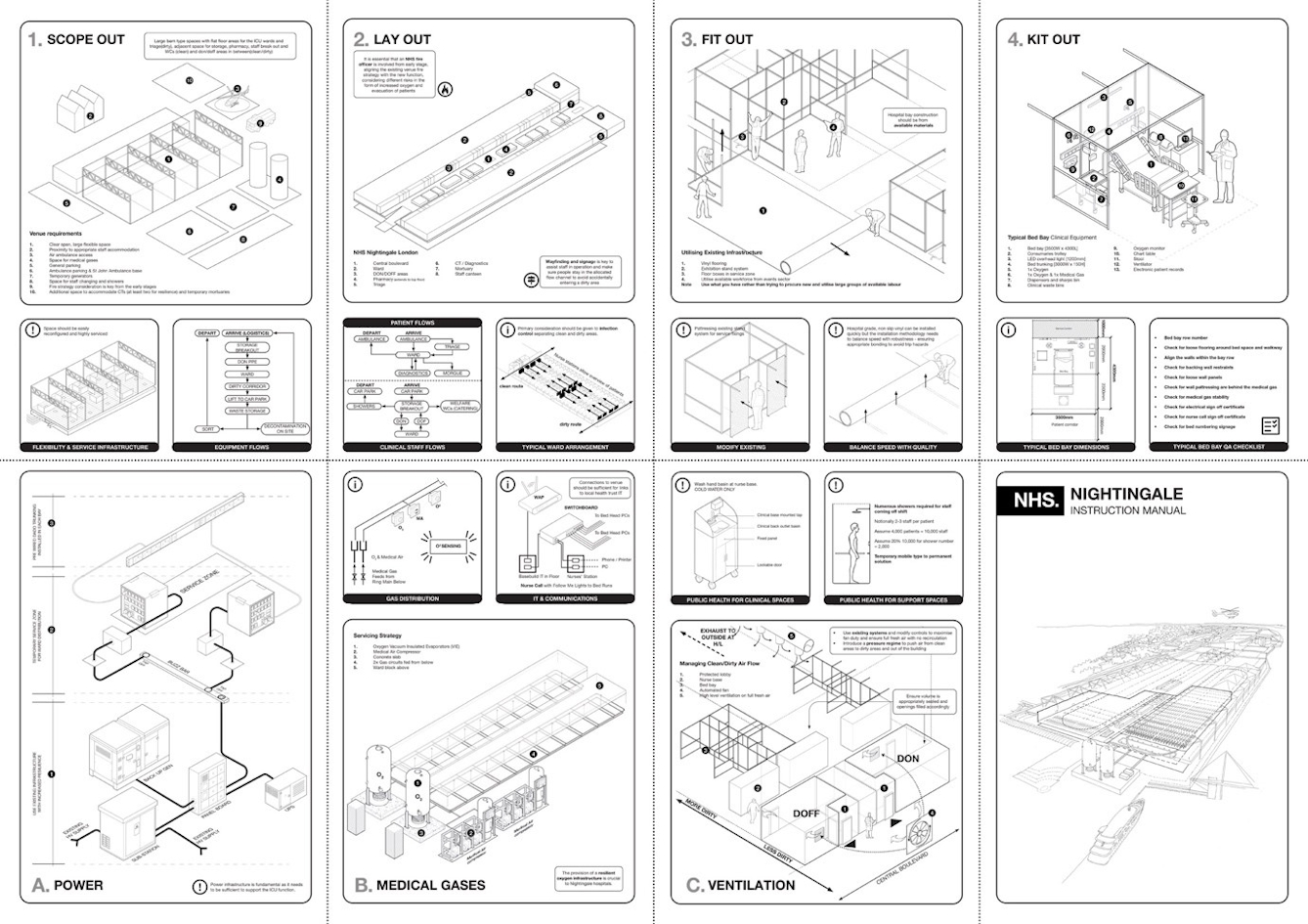

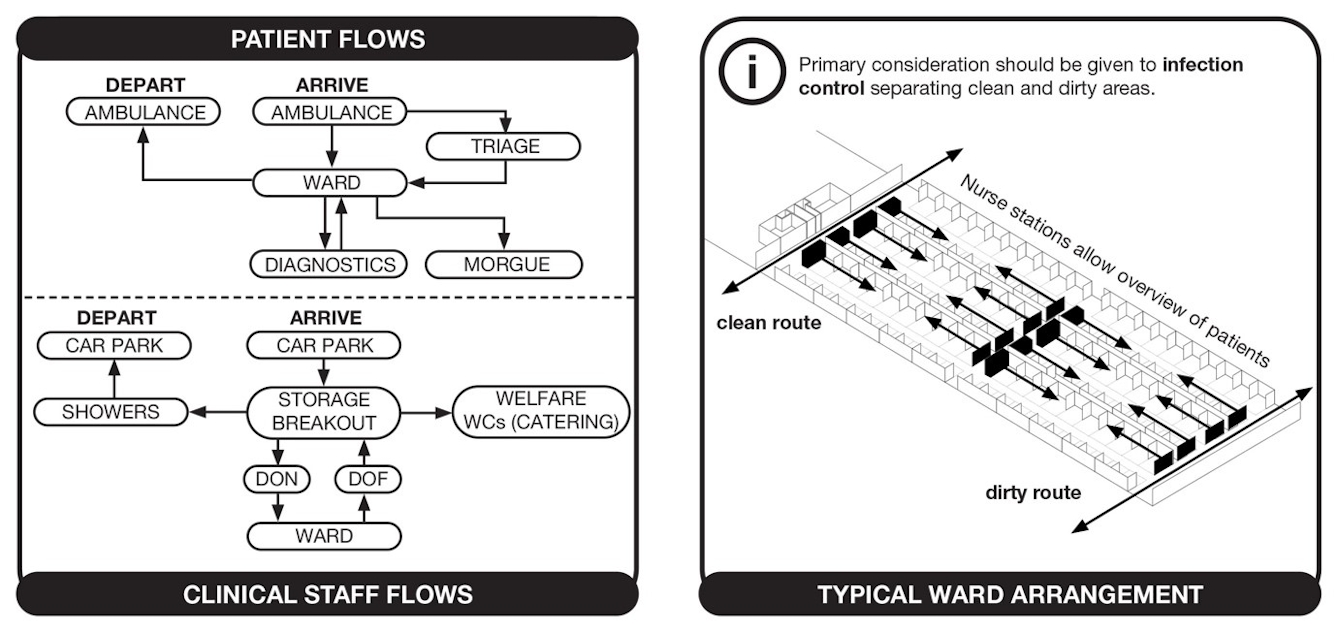

It is interesting to see the impact of these historical designs on solutions to increasing intensive care capacity during the Covid-19 pandemic. The influence of ‘Notes on Hospitals’ can be observed in the design of the NHS Nightingale hospitals, strategically configured to avoid the transmission of the virus by contact. Behind the work of architects and engineers at BDP, the firm that developed the guidelines for the pop-up hospitals in the UK, are clear similarities to the principles that Nightingale herself prescribed.

Nightingale’s pavilion ward was planned to be effective in terms of recovery as well as logistics, with the right dimensions to efficiently supervise it. We can see similar concerns in the layout of London’s ExCel Nightingale Hospital. It provides sufficient space to keep patients apart, as well as the right distances to offer good visibility for nurses to attend the patients. However, it is the word ‘contagion’ that plays a fundamental role in the inception of the hospital. Nightingale believed that sanitary arrangements had a critical influence in preventing the spread of diseases.

Defined by Nightingale as the “the communication of disease from person to person by contact”, the term ‘contagion’ is also a key aspect of our contemporary global health problem. Then as now, the way coronavirus spreads has a crucial impact on the shape and construction of the hospital space. The main aim of the critical-care unit is to isolate the infected patient to stop spreading the virus and to treat the specific symptoms.

There were numerous practical reasons for locating 2020’s first emergency field hospital in east London, not least because there was a plan for medical and other staff working in the hospital to stay on the University of East London campus. However, there is also another connection with Victorian England, as east London was the site of cutting-edge children’s hospitals, such as the North-Eastern Hospital for Children in Hackney Road. As in the present, they were created in existing premises to mitigate the devastating pandemic of ‘Asiatic’ cholera, which claimed thousands of lives in east London in 1866.

Founded by philanthropists, pioneering health institutions signified a milestone in the social and urban history of London by following the very same guidelines set out by Nightingale. Their success was due to the creation of environments where cleanliness, space and ventilation were the fundamental conditions of an effective space for treating the sick. It is remarkable that, after two centuries, Nightingale’s design principles are still relevant to respond to the current pandemic.

About the author

Iria Suárez

Iria Suárez is a design historian and multidisciplinary designer working within the field of architecture. She graduated from the Royal College of Art and Victoria and Albert Museum with an MA in History of Design. She is interested in design and wellbeing, and her research focuses on the history of the design of children’s hospitals in London.