Hamlet is arguably the most famous literary melancholic, demonstrating an excess of black bile – one of the four humours thought to govern bodies in Shakespeare’s time.

Hamlet, the melancholic Prince of Denmark

Words by Nelly Ekströmaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Article

The Elizabethan melancholic

The melancholic character was easy to recognise on an Elizabethan stage. Lean and pale, moving slowly, sad and brooding, perhaps suspiciously looking around for enemies. Black bile, the humour that dominated this temperament, was connected to the cold and dry element earth, to old age, and all things dying and rotting. Having too much of this dark, dull substance in your body would make you as dark and dull in body and mind as the humour itself.

In Shakespeare’s comedies, like ‘The Tempest’ and ‘As You Like It’, there is often a melancholic figure who acts as foil to the more optimistic leading characters. But in the tragedies they are more often the leading characters, generally elderly men. Ageing was in itself seen as a process of gradual drying of the flesh and cooling of bodily humours. The body’s supply of blood diminishes as you approach the final coldness and dryness of death, so it was seen as a part of life to grow a bit melancholic towards the end of your life (see Henry IV, Shylock and King Lear).

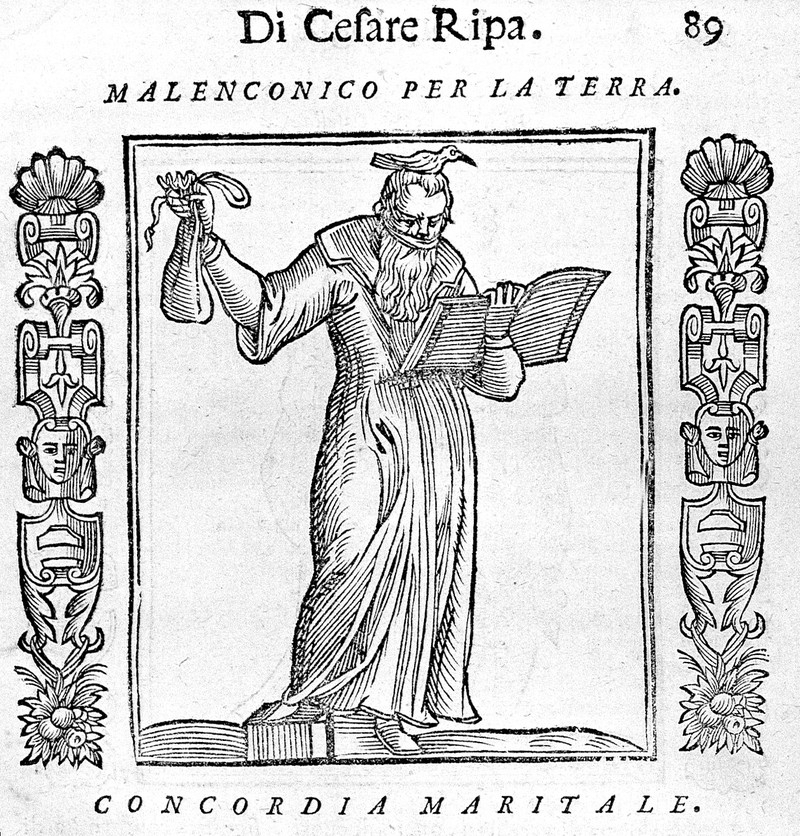

Cesare Ripa, 1610. Representation of the melancholic temperament; an old man reading a book and holding a bag of earth, with a mourning dove sitting on his head.

Prince Hamlet is probably the most famous melancholic in literature. Although he’s young, he still ticks all the boxes. Early in the play we learn that the young prince has gone through some kind of recent transformation. As he describes it himself:

“I have of late – but wherefore I know not – lost all my mirth, forgone all custom of exercises, and indeed it goes so heavily with my disposition that this goodly frame, the earth, seems to me a sterile promontory; this most excellent canopy, the air – look you, this brave o’erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire – why, it appears no other thing to me than a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours.”

Black bile, the humour of melancholy

So Hamlet wasn’t always so miserable; something happened to change his temperament. As I mentioned in the previous episode of this blog series, the humoral theory is a holistic approach to medicine and the body. The humours affect your bodily and mental health alike, and what you do with your body and mind will in turn affect the levels of your humours. Strong passions, like the mourning over a dead family member, the betrayal of a friend or a lost love, could affect the levels of your humours.

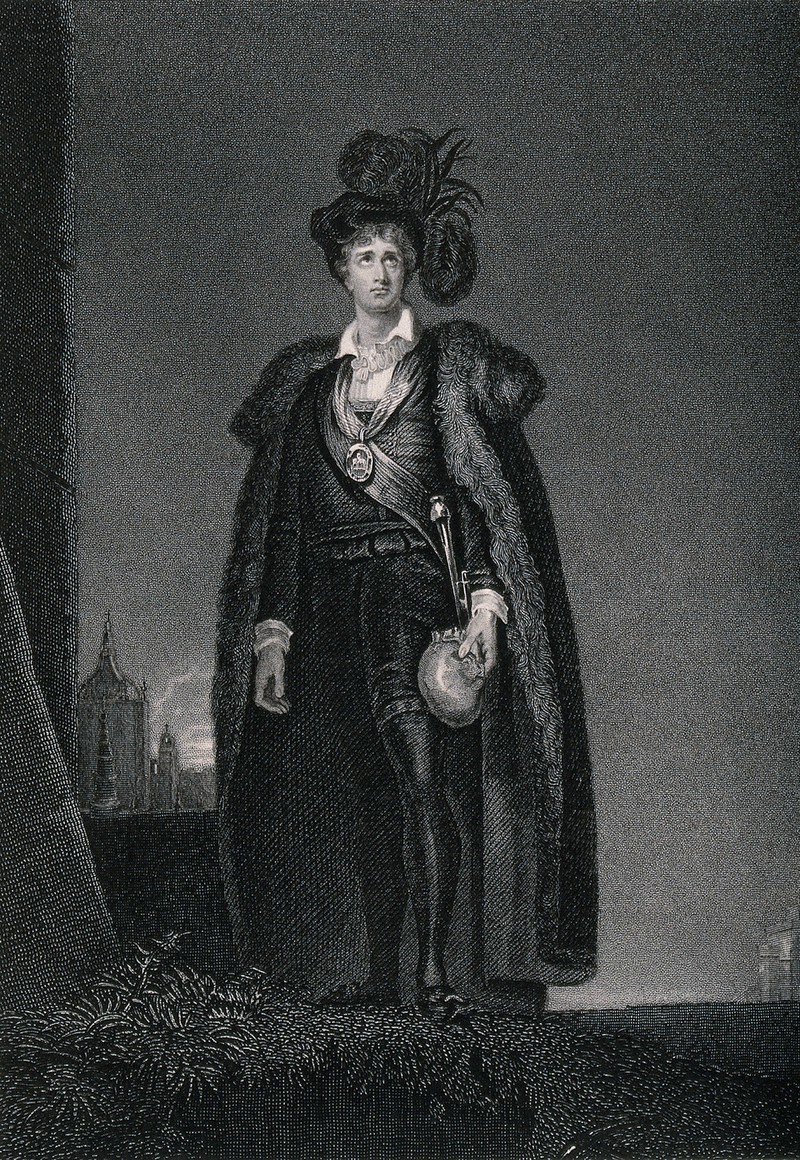

Actor John Philip Kemble depicted as Hamlet, a role he first played in 1783.

Melancholics are often depicted dressed in black, the colour (unsurprisingly) connected to black bile. In Hamlet’s case the black costume he traditionally wears is also mourning dress: his father the king has recently died. When in mourning, it’s not uncommon to withdraw and find somewhere to sit and cry. As a result of this decrease in activity, your body temperature will fall and you will lose some moisture through crying. This will turn your body cold and dry and, of course, build up your levels of black bile. Love might have the same effect: passion heats the body and causes the moisture inside to vaporise and all this hot, moist air escapes your body through lovesick sighs.

The characters around Hamlet are worried by his melancholia. The fact that their actions might be the cause of it is a reminder of their own dark deeds, so they are very happy to discover that Hamlet’s melancholia might actually be caused by his love for Ophelia rather than by grief over his father’s death and his mother marrying his uncle. Hamlet’s sanity is one of the major themes in the play. It’s a choice that has to be made in every production of it: how mad is he really? To what extent is he just acting?

A natural excess of black bile could make you cautious and analytical. Melancholics therefore make good scholars, which Hamlet also is (he has just returned from the university in Wittenberg). Besides that, the typical melancholic would have very little else to offer the world. The black bile would weigh on you, and make you passive, sad, dull and indecisive. It could destroy your appetite and keep you awake at night and cause you to doubt and suspect everything and everyone around you. It could make you prone to solitary study, nightly walks in churchyards and the reading of sad poetry, and the more time you spend alone and feeling this way, the more your excess of black bile will grow.

A person with this kind of temperament was not seen as productive and active in society like the warm-blooded sanguines and cholerics were. Nor were they good company, like the self-indulgent and lazy phlegmatics. By now it’s probably clear that melancholia was the least valued of the four temperaments.

Treating depression in Shakespeare's day

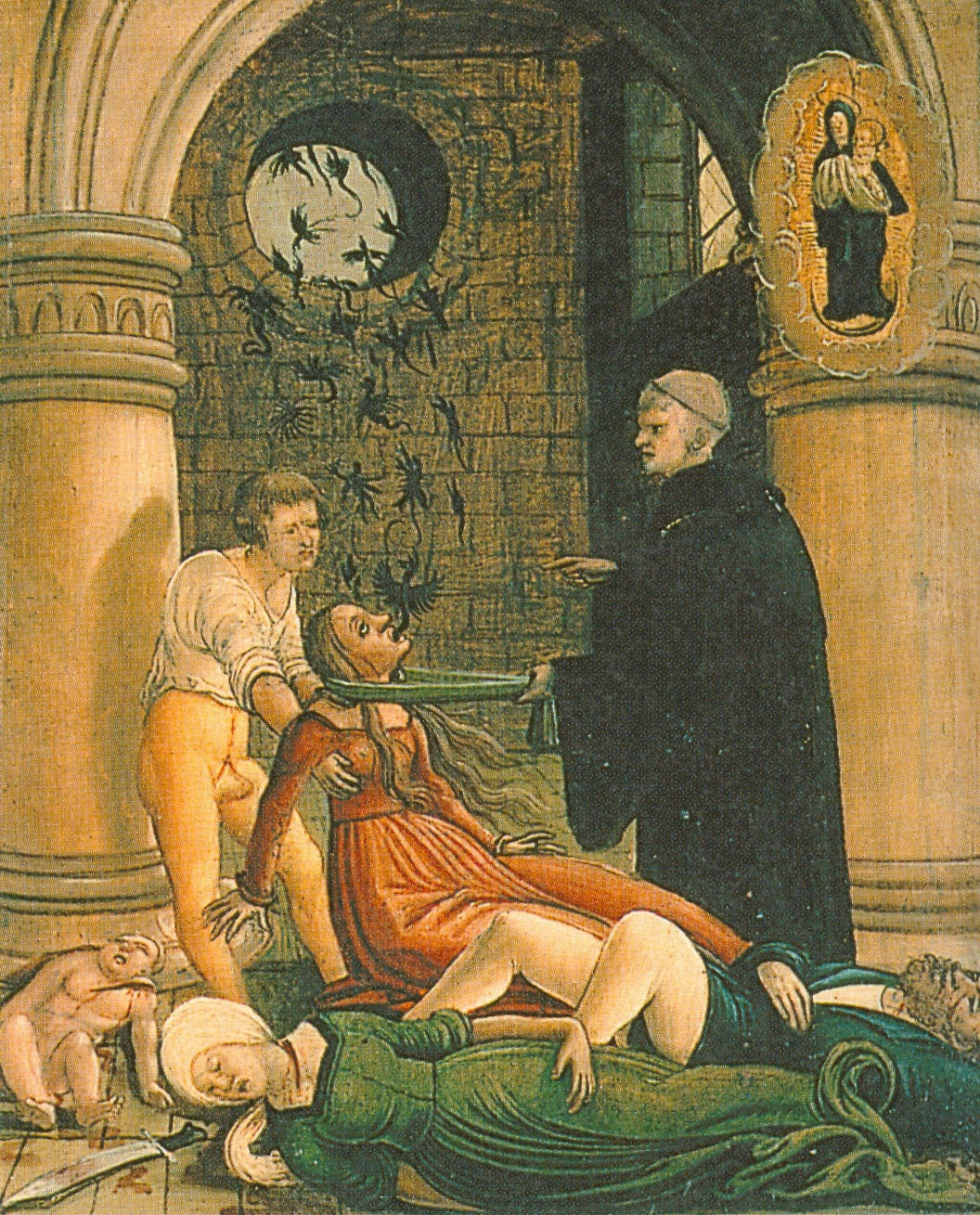

Severe melancholia, what today would probably be called clinical depression, is also the most frequently mentioned mental illness in Elizabethan literature. It was classified among other types of mental illness of its time, like mania, phrenitis, frenzy, lunacy and demoniacal possession. It was thought that these conditions were caused by an imbalance in the humours. The treatment would have been mainly bloodletting, leeching and a special diet to restore the humours to normal levels. Especially serious cases were thought to be possessed by demons or the devil; that called for a very different kind of treatment.

Exorcism in the 16th century.

In Shakespeare’s day, only very wealthy people could afford a doctor and the medicines or treatments he would recommend. Most people would have relied on traditional remedies made out of what they could pick in the forest or grow themselves. The ‘physic garden’ or patch, would be as important to the household as the kitchen garden, and it was common knowledge how these plants and herbs were used. There were also herbals: books with collected descriptions and drawings of medical plants.

Herbal, 16th century.

Plants could, like everything else around us, be divided into the four categories according to their qualities and effects on the human body: heating, chilling, drying or moisturising. Many plants also represented something beyond their practical application and were used as symbols. Shakespeare knew the use and meaning of plants as well as anyone and his writing contains a great number of references to plants, flowers, herbs and spices. To modern fans the references and symbolism are almost like code, but for Shakespeare’s audience ‘peaseblossom’ would mean the same and be as easy to understand as Viagra is to us.

In Ophelia’s last scene in ‘Hamlet’, she comes on stage with her arms full of flowers. Each one of them a symbol, carrying a message to the person she hands it to.

“There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance. Pray you, love, remember. And there is pansies, that’s for thoughts… There’s fennel for you, and columbines. There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me. We may call it ‘herb of grace’ o’ Sundays. – Oh, you must wear your rue with a difference. There’s a daisy. I would give you some violets, But they withered all when my father died.”

Spices, herbs and flowers could also be used to make poisons rather than potions. Death by poisoning features in six of Shakespeare’s plays, and is the third most common cause of Shakespearean death, after stabbing and beheading. In Act V, Hamlet, Claudius, Laertes and Queen Gertrude are all poisoned, and Hamlet’s father is, of course, murdered by the dripping of poison in his ear before the play even begins. This is how Laertes prepares to revenge his father’s murder in a duel with Hamlet:

“I will do’t./And for that purpose I’ll anoint my sword./I bought an unction of a mountebank,/So mortal that, but dip a knife in it,/Where it draws blood no cataplasm so rare,/Collected from all simples that have virtue/Under the moon, can save the thing from death/That is but scratched withal. I’ll touch my point/With this contagion, that if I gall him slightly/It may be death.”

Black bile was connected to the element earth, and the word ‘earth’ is mentioned a lot in Hamlet. In all, the word ‘earth’ (or variations of it) is mentioned 23 times in the text. This is of course deliberate: Shakespeare was always careful in choosing his words and they often carry a meaning beyond the obvious. ‘Richard II’ is another tragedy with a melancholic leading character and ‘earth’ is mentioned in it 24 times. The word is quite rare in Shakespeare’s writing otherwise: in ‘The Taming of the Shrew’, a play without melancholics, the word is only used once. This repetition of ‘earth’ constantly reminds us of the underlying theme of the play.

“Something is rotten in the state of Denmark.”

And that rottenness is the cause of this tragedy. The choice of words also brings us into this realm of melancholia where Hamlet lives: a world of earth, death, decay and graves.

About the author

Nelly Ekström

Nelly Ekström is a Visitor Experience Assistant, bringing the galleries and exhibitions to life.