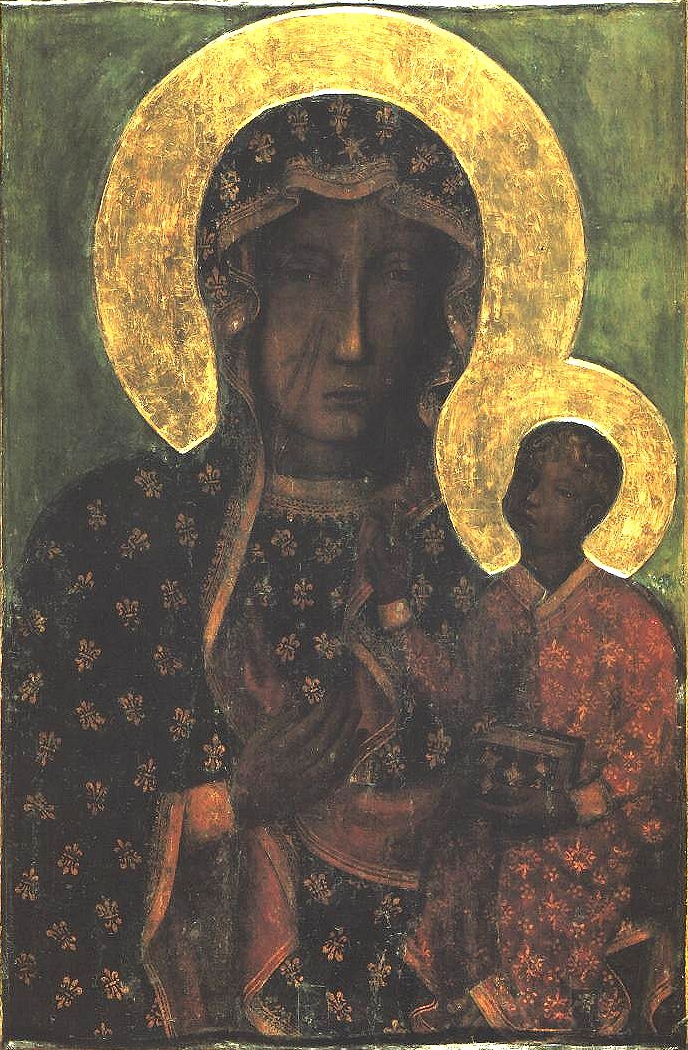

Found in hundreds of Catholic churches across Europe and Latin America, the Black Madonna, a depiction of the Virgin Mary with dark skin, remains one of the most mysterious and controversial religious icons. She has a complex history and many possible meanings.

Of our own Black Madonna displayed in Medicine Man we know little, except that she was bought by Henry Wellcome and represents the original Our Virgin of Guadalupe found in the Extremadura region of Spain. But the painting incites much interest and surprise among our visitors, as it’s often the first one of its kind they have encountered.

This was also the case for me. I remember hearing about the Black Madonna as a child, but I can’t recall ever having seen one. I grew up in a Catholic country, but was not raised in the religion.

It was later, during my degree, that I became interested in religious iconography from an art history perspective (although study of the Black Madonna was not part of the curriculum, and representations of her were never mentioned).

Henry Wellcome (1853–1936) bought this painting of Our Virgin and Child of Guadalupe, displayed in our Medicine Man gallery, but the year of purchase is not recorded.

Black Madonna images, dating mostly from the medieval period, appear in the form of paintings and sculptures carved out of wood and stone. The oldest examples, and the great majority of them, are found in European countries. They are often in the most venerated shrines dedicated to the Virgin Mary and have attracted thousands of pilgrims for centuries.

The Black Madonna of Częstochowa and Montserrat

Among the most well known are Our Lady of Częstochowa in Poland and Our Lady of Montserrat in Catalonia. In these locations, their meaning and significance go beyond religion. They are also powerful symbols of national identity.

Most of us are familiar with depictions of the Virgin Mary as fair-skinned, blue-eyed and blonde. A first encounter with a Black Madonna is intriguing. Invariably, the first question crossing most of our visitors' minds, no matter their country of origin or ethnic background, is: why is she black?

This is where the controversy begins, with conflicting views between the Church, academics and researchers.

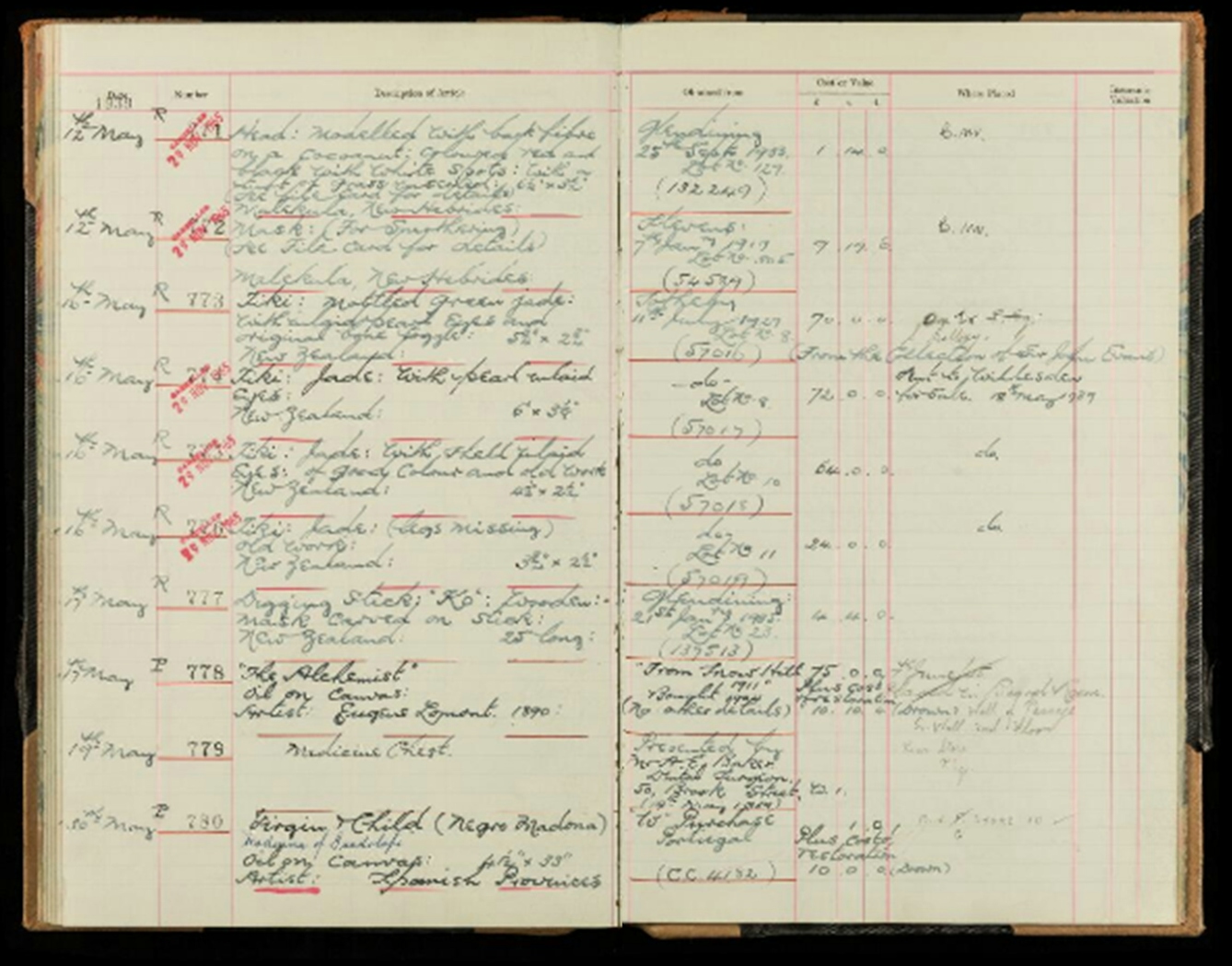

The painting was first entered in our museum accessions register on 30 May 1939 (bottom of the pages); this is how far back we’re able to track it. The register locates its provenance in the Spanish provinces. At some point, it made its way to Portugal, where it was bought by Henry Wellcome for 1 shilling plus £10 for restoration.

Accidental factor, biblical verse or Mother Earth?

The most commonly accepted theory deems the images' skin colour to be accidental: these Madonnas were once white, but have darkened through ageing and exposure to candle soot.

This explanation is as much anecdotal as it is a symptom of cultural whitewashing.

It is hard to believe that all these images, represented in various materials, would have aged in a particular way that capriciously turned only their faces and hands black. (The same phenomenon has not been observed in equal proportion in representations of Jesus Christ.)

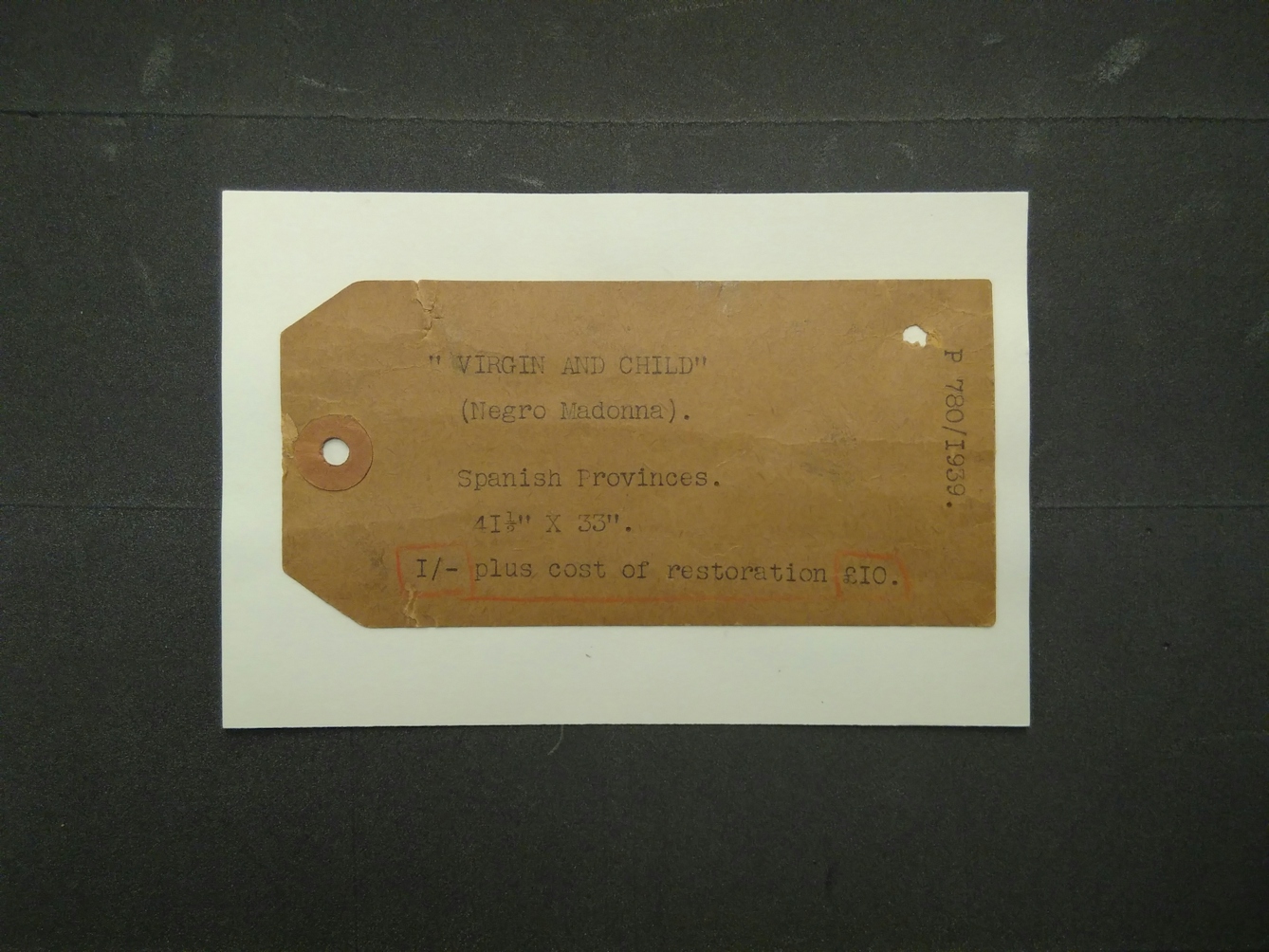

This cataloguing label for our painting was probably written in 1939, when the painting was entered in our registers. The concept base of most museum collections from the 18th to the early 20th century was evolutionary philosophy, which assumed the superiority of Western cultures. This way of thinking informed the language used to describe and catalogue museum objects. The use of the term ‘Negro Madonna’ here is a good example of this bias.

Another explanation associates the Black Madonna with a biblical verse, saying that it refers to the words of the Bride in the Song of Solomon: “I am black, but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem.” This theory at least accepts a clear intention behind the blackness of the images.

But I, and many others, were still not convinced.

As there has always been exchange and continuity between different cultures and religious systems, I am strongly inclined to agree with historians who argue that the Black Virgin Mary is linked to ancient pre-Christian worshipping of Mother Earth and other female divinities.

These divinities are shared ancestors between her and goddesses such as Cybele, Artemis, Gaia and Isis (some of them often portrayed as black). In this case, black is not only a mystical colour associated with fertile earth, but also an expression of an ancient cultural memory that connects us back to our early history in Africa.

Pre-Christian religions

What form these ancient religions took we may never know; this is an area of much conflict and speculation. But what we can observe by looking at different religions centred on mother goddesses through the ages is that associations between motherhood, womanhood, fertility and Earth have been strong and recurrent across religions.

The most evident synthesis is the ancient Greek goddess Gaia, a female personification of Earth, creator of all life, who gives birth, nourishes and feeds us all, and to whom we shall return when we die.

These ancient religions gradually changed or disappeared as societies became structured within the patriarchal model, and religions centred on a male figure were superimposed.

But some elements still survive. The celebrations of the summer solstice, still very much alive in Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, have a direct link to pre-Christian pagan rituals. Even when we casually refer to Mother Nature, we are unconsciously echoing the same distant past.

Statue of Isis nursing Horus, Egypt, 600–30 BCE, which predates Christian representations of the Nursing Madonna.

It was certainly not unusual for Christian churches to be built over pilgrimage and worship sites, where pagan shrines and temples once stood, but the same rituals and practices continued and were absorbed by the new officially accepted faith.

This might well be the case of Our Lady of Willesden (the Black Madonna of London!). Unfortunately, the original was destroyed during the English Reformation in the 16th century. It is said to have been publicly burnt at Chelsea alongside several other Catholic images.

A couple of centuries later, two statues were made in honour of the Black Madonna of Willesden. One can be found in the Roman Catholic Church of Our Lady of Willesden, and the other in the Anglican St Mary’s, Willesden, on the same ground as her predecessor.

The origins of the original Black Madonna of Willesden may be lost in history, but it is believed that the site has been a centre of pilgrimage since Anglo-Saxon times, and that the water from the natural well, which still runs under the church, has holy and healing properties.

Our Lady of Willesden. Artist Catharini Stern was commissioned to carve this statue in honour of the original Black Madonna of Willesden. The new statue has been housed in St Mary's, Willesden since 1972.

Looking back to look forward

But what can she still tell us today? What significance can she have beyond religion and faith? I believe icons like the Black Madonna can do a lot for us. They can help us change the way history is told. They can speak about all the other histories that have been neglected in favour of Western, male-centric narratives we’ve become so used to, and in which museums are traditionally grounded.

While delving in our Library archives, trying to trace back the history of our Black Madonna painting, I found that it was originally catalogued as ‘Negro Madonna’. This was 1939, when the presence of examples of racist language, such as this one, would be the norm in museums.

In the last few decades we have seen the onset of movements calling out for the celebration of the history of oppressed groups. These movements have been crucial in compelling museums to start the long process of confronting and publicly addressing the problematics of their legacies. They also continue to inspire new ways of talking about issues of institutional racism, sexism, and inequality still present in our society today.

The everyday conversations we have with visitors are part of this process of change. Objects like the Black Madonna make for great starting points of conversation.

About the author

Daniela Vasco

Daniela works at Wellcome Collection in the Live Programmes team, and her background is in Fine Arts. She is interested in connections between art, science and religion. Her research and public engagement focus is on gender identity and politics, colonial history and museum collecting.