What made teenagers in the 1960s puzzling, threatening – and even alien? Ken Hollings explores the legacy of postwar youth culture and the rise of the mysterious ‘Generation X’.

The unearthly children of science fiction’s Cold War

Words by Ken Hollingsaverage reading time 16 minutes

- Article

We open on a foggy night in London. Patrolling the grainy monochrome murk with his flashlight, a policeman checks the locked entrance to a scrap merchants’ yard before moving on. The gates swing open to reveal a piled-up assortment of discarded items, including a police public call box, which emits a low modulated hum. The title ‘An Unearthly Child’ appears in large white letters across the centre of the screen. It’s the autumn of 1963, and the BBC has just launched its new children’s television programme ‘Dr Who’.

Before we meet pop culture’s most famous time traveller, we are introduced to his granddaughter. Fifteen-year-old Susan Foreman attends the local school, where she represents a constant puzzle to her teachers. She seems to know more about physics and history than they do, but is completely unfamiliar with basic aspects of daily life. She believes, for example, that the United Kingdom has already gone decimal, even though that’s still eight years away.

A little elfin

In other respects, she is a typical teenager of the period. “Susan is listening to guitar rock music on her transistor radio,”’ the script specifies. “She looks a little elfin, like Audrey Hepburn.” Susan says she likes walking in the dark: “It’s mysterious.” When one of her teachers warns her to be careful because “there’ll probably be a fog tonight”, Susan just says “mmm” and smiles. “Nothing about this girl makes sense,” one of her other teachers complains. But then why should it? She’s just a teenager. That Susan is the granddaughter of an alien time traveller helps explain who she is, but not why she seems so opaque to adult eyes.

Nodding to the beat of her transistor, Susan appears unearthly precisely because she is such a familiar part of the Cold War landscape. Hollywood melodramas like John Frankenheimer’s ‘The Young Stranger’, in which a teenager acting out against his father is charged with criminal assault, had already identified adolescence as something unreadable and misunderstood – a problem “that strikes at the very heart of millions of American homes”, according to the movie’s 1957 trailer. The generation gap was still something relatively new: bracketing youth, technology and the future together, while traditional values and social roles were slowly being confined to the scrapyard.

Susan embodies this proposition taken to its logical conclusion: the adolescent as extraterrestrial presence. Impacted and shaped by Cold War pressures, unresponsive to the standard psychological practices of the age, the ‘unearthly child’ becomes a distinct theme in British popular culture from the late 1950s to the late 1970s.

Representative of a radically different reality, this new kind of young stranger throws long shadows into the present through a succession of remakes, sequels and adaptations. It starts with ‘An Unearthly Child’ being repeated the week after its original transmission: the BBC was concerned that its impact might be lost amid the media coverage following the assassination of President Kennedy.

Wholemeal bread and all the rest of it

Audrey Hepburn and John F Kennedy represent two significant Cold War ‘gaps’. In the 1957 musical ‘Funny Face’, alongside her appreciably older co-star Fred Astaire, Hepburn plays a young bohemian, her presence in the movie associated with rock ’n’ roll, philosophy and jazz choreography. Meanwhile presidential candidate Kennedy pounded the Eisenhower administration about a perceived ‘missile gap’ between the United States and the Soviet Union, tilted in the latter’s favour.

The ‘unearthly child’ narrative that connects youth with outer space and Cold War paranoia is symptomatic of a culture riddled with cracks and fissures. An early, relatively innocent version is ‘Supersonic Saucer’, a 1956 Gaumont-British Picture Corporation children’s cinema feature about a baby Venusian visiting the Earth. In this space-age retelling of Edith Nesbit’s 1902 novel ‘Five Children and It’, Meba, a small, ghostly alien with staring black eyes, is befriended by three young pupils stuck at a boarding school over the summer holidays. “It’s really most peculiar,” one of the girls exclaims on first contact. “I feel as though I can see what Meba’s thinking about.”

The notion of an unseen psychic link between child and extraterrestrial will recur. The children act as Meba’s parents, chastising the space creature when it steals cakes or sets a room on fire in attempts to please them. “He finds us most difficult to understand because we wish for things, and the moment we get them we don’t want them,” the girl explains. “Poor Meba.”

The alien Meba from ‘Supersonic Saucer’ (1958).

Pale and featureless, incapable of expression but with big eyes that brim with tears, Meba is an innocent blank upon which the children can project their fears and fantasies, telling their space visitor not to “set fire to the house or fly to the moon or something silly like that”. John Wyndham’s 1957 novel ‘The Midwich Cuckoos’ offers a more adult version of the same encounter. “Never know what those Ivans [Russians] are up to,” an army intelligence officer remarks grimly of the strange happenings in the village of Midwich. An alien landing appears to have resulted in all the childbearing members of the small rural community becoming spontaneously pregnant.

The outcome is a generation of golden-eyed creatures with delicate features and frightening mental abilities. Everything about them is a problem – parents, educators, scientists and soldiers are confounded by their very existence. Not so the chief constable, who thinks the children are being treated unnecessarily as special cases. “Self-expression, co-education, wholemeal bread and all the rest of it,” he thunders. “‘Damned nonsense. More frustrated by being different about things than they would be if they were normal.”

The Children, as they are called, join the rest of this postwar generation in being the first to emerge from under “the fatherly eye” of the new welfare state, in which the government aimed to protect and support the wellbeing of its citizens from cradle to grave. To be “different”, the chief constable suspects, is to lose all inhibition under the influence of such pervasive and indulgent control. Following his authoritarian outburst, the Children psychically reduce him to an abject thing crawling across the carpet, whimpering. Poor Meba.

Wyndham’s alien invasion is set in a timeless rural landscape. The town of Midwich, according to his description, has hardly changed in centuries, in stark contrast to the speed of the Children’s development. At a time when toy space helmets, rockets and ray guns find a place in the nursery, the Children are never seen to laugh, run or play.

Although still very young, they look “every bit of sixteen” and are addressed as adults once they start terrorising the local community. Adolescence becomes a dangerous shift from ‘innocent’ childlike behaviour. “We don’t seem to be good at integrating novelties with our social lives, do we?” Gordon Zellaby, the town’s resident philosopher, remarks, before adding that youth welcomes “the unconventional, the unregulated”.

A superior species

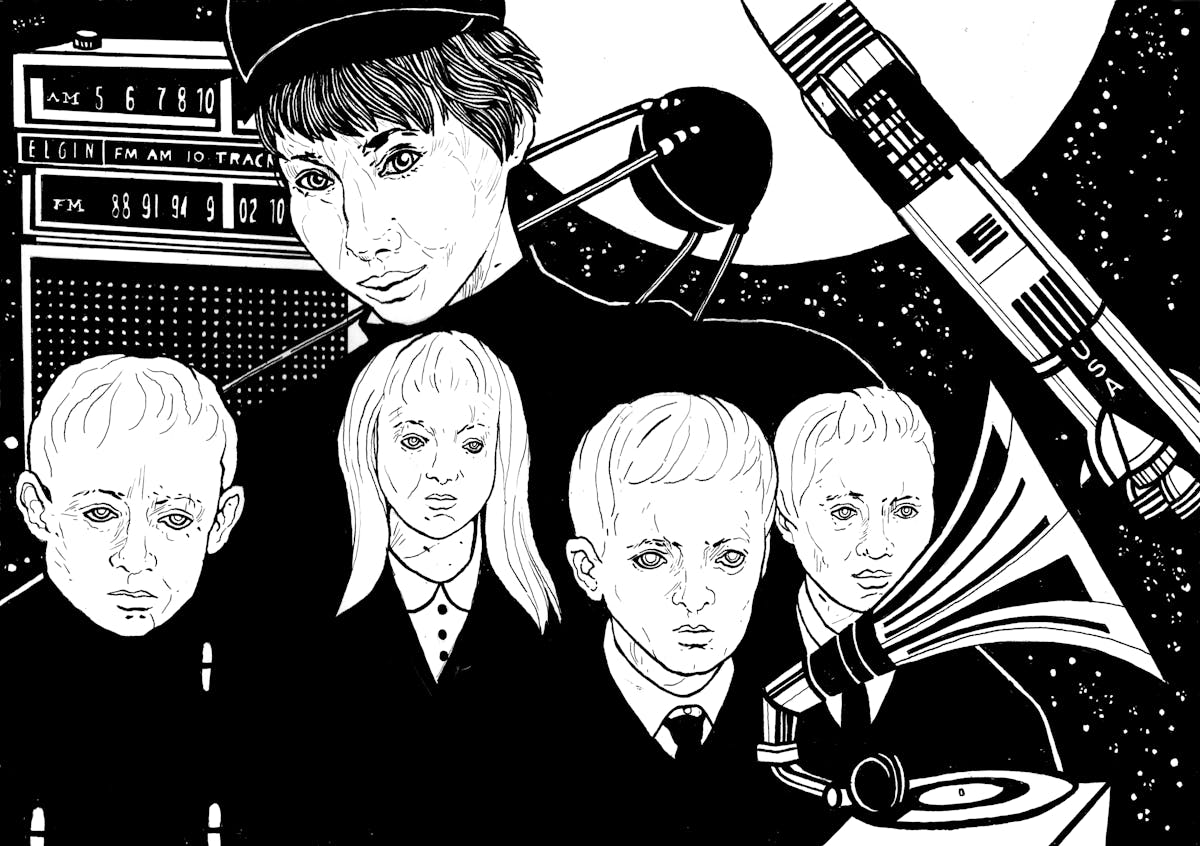

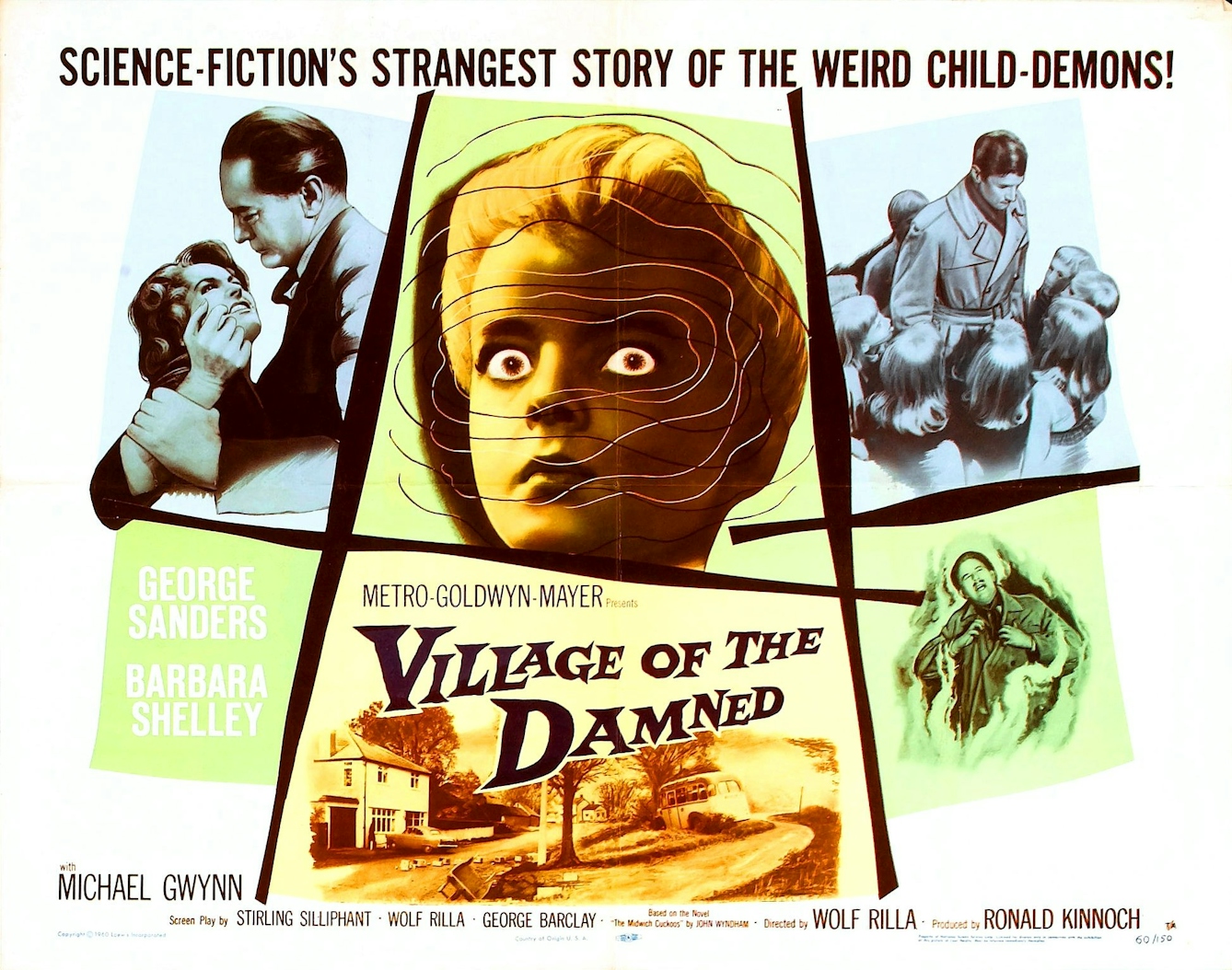

The generation gap is even clearer in ‘Village of the Damned’, the 1960 film adaptation of ‘The Midwich Cuckoos’. Veteran Hollywood actor George Sanders plays the philosopher Zellaby, while the Children are set apart by their blond hair, high foreheads, staring eyes and calm demeanour. When Midwich’s adult population is put into a deep sleep prior to the alien inception, the moment is dramatically brought to life by the sound of an unattended wind-up gramophone slowly running down. It marks the passing of an old medium: a modern teenager would surely never listen to anything so outmoded.

‘Village of the Damned’ (1960), an adaptation of John Wyndham’s 1957 science fiction novel ‘The Midwich Cuckoos’, featured an eerie race of children with blond hair, high foreheads and staring eyes.

“These children all want to dress alike,” Zellaby remarks. Their choice of clothing may be conventional, but their collective adherence to it chimes unsettlingly with the times. The 1950s and 1960s were marked by a proliferation of subcultural uniforms: from beatniks and Teddy boys to mods, rockers and hippies. Unlike Wyndham’s novel, ‘Village of the Damned’ is located in a recognisably contemporary landscape: the Children’s takeover is staged against displays of Oxydol detergent, Velvet Lady ices and HP Sauce in the village shop.

‘Children of the Damned’, a 1964 sequel, exchanges pop-culture references for Cold War paranoia over the balance of power between East and West. A background detail in Wyndham’s original novel makes passing reference to War Office reports that the USSR had a “similar flock” of Children but very quickly wiped them out. In this new movie, the first “standardised IQ test for all over the world” throws up a handful of anomalies in Nigeria, India, China, Russia, USA and the UK. These five young geniuses eschew the visual uniformity of the original Children to highlight the individual threat they each pose to an already fragile global stability.

All the offspring of “an unstable mother and no trace of a father”, they become the assets of their respective governments until it becomes apparent that they are destined to disrupt the old order. “They’re not human…they’re a superior species. They’d beat us every time,” is the film’s repeated phrase. Highly advanced both intellectually and spiritually, the Children remain an unsolvable problem both to humanity and to themselves. When first asked why they are here, one child’s reply is simple: “I don’t know.” Later his answer is more specific: “To be destroyed.”

The young respond best to radical change in these Cold War fantasies because they are radical change – or at least appear to inhabit it as a natural environment. Education and social psychology are presented as tools to mediate that relationship, but their presence proves shadowy and far from adequate. In ‘Children of the Damned’ Military Intelligence ignores the child psychologist in favour of the geneticist’s advice: these kids, it seems, possess “the cells of man advanced maybe a million years”.

Our teachers will be dead

In Joseph Losey’s 1963 film ‘The Damned’, educationalists and the military square off against each other at a secret compound housing a generation of radioactive schoolchildren. “Your security men have the imagination of prison wardens,” one teacher complains. “If it were up to you, you’d turn these children into beatniks,” sneers a representative from the War Office. “In the circumstances, would that matter?” a fellow academic retorts.

Screened from public view behind barbed wire, armed guards and intruder alarms, the Children are impervious to the harmful effects of radiation and consequently treated as Britain’s last line of defence in a nuclear war. Cut off from the outside world, the Children remain unaware of their destiny. “We’re in a huge spaceship and we are going to a star,” one child says of their protracted confinement. “They’re teaching us the history of Earth so we can build a civilisation when we get there. It’s going to be a long trip and by the time we get there, our teachers will be dead.”

Filmed for Hammer in 1961 but not released for another two years, ‘The Damned’ depicts British society entering an “age of senseless violence”. Outside the compound a gang of teenage bikers led by a sexually repressed young dandy haunt the local seaside town, beating up and robbing tourists. The film’s title song, ‘Black Leather Rock’, is a cheerily swinging incitement to smash, crash and kill. But there is more than a heavily guarded perimeter separating the Children from the rockers. Adolescence itself becomes a threat. “Sit up please,” the chief scientist admonishes his young captives. “I hope we’re not in our rebellious mood this morning.”

The Children, however, are already devising ways of avoiding adult scrutiny: building their own codes and mythology, particularly about their future. “You are always talking about ‘when the time comes’,” one girl retorts impatiently. “What we want to know is: when does the time come?” The chief scientist explains that they’ll know when they’re older: a formula that conflates adulthood with the “universe of ashes” that awaits them. Safely locked inside their Cold War atomic Eden, the Children are protected from the torments of adolescence. “I know it’s kid’s stuff, knocking about in a gang,” a rocker complains from outside, “but what else is there to do?”

The Evening News reported youths yelling, “Junk! Rubbish!” at early London screenings of ‘The Damned’. “I’d like to think that a new sort of man is evolving out of my generation,” a teenager tells journalists Jane Deverson and Charles Hamblett in 1963, “but looking at my contemporaries I don’t see any signs of such a development.”

The only thing you’ve got over them

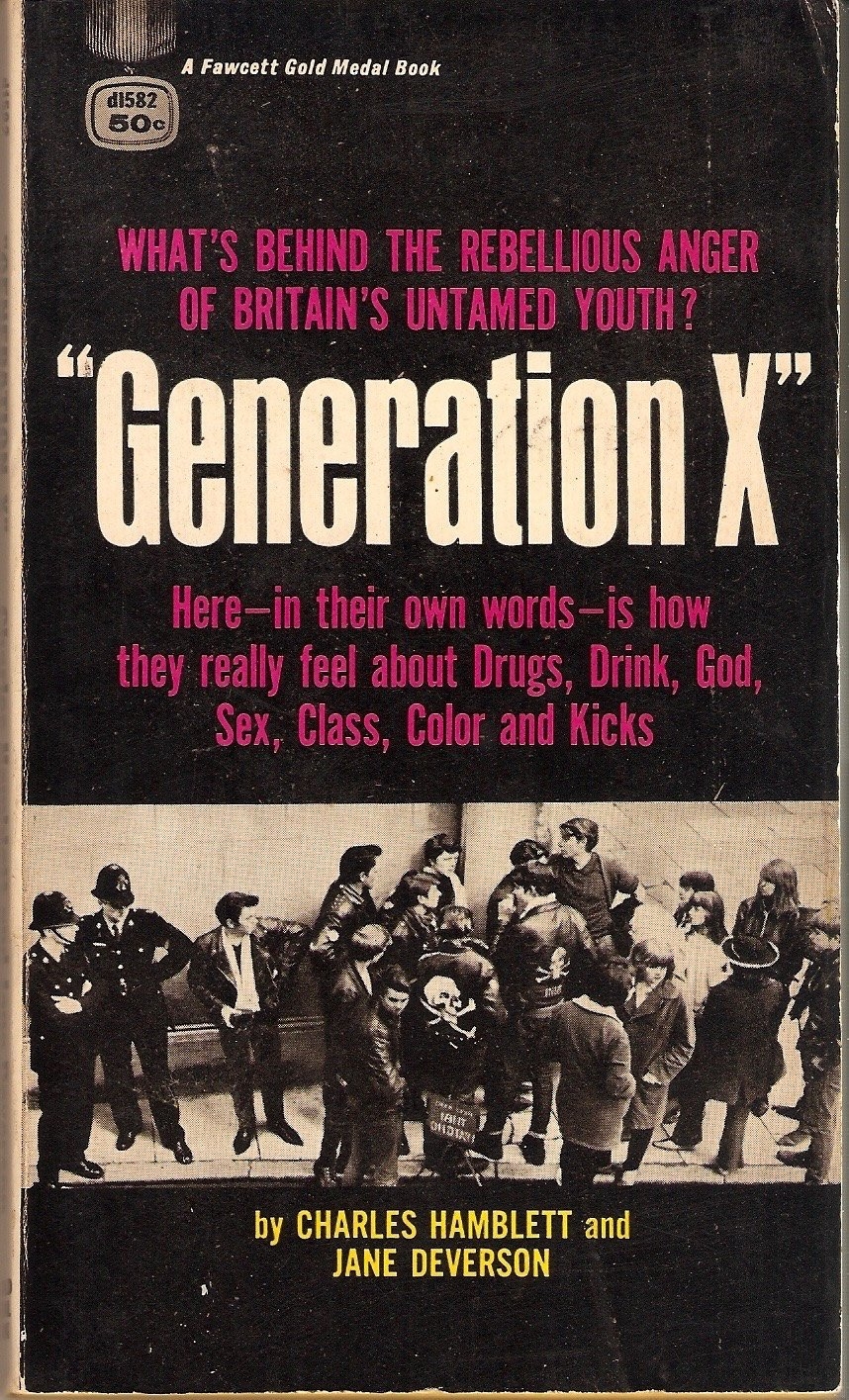

Deverson and Hamblett’s ‘Generation X’ was a bestselling volume of pop sociology, first published in 1964 in the shadow of the Kennedy assassination. It offered an outspoken and complex profile of an emergent Cold War subculture that saw itself increasingly at odds with the post-World War II order. “Call it a welfare state?” protests a female member of a biker gang similar to the one depicted in ‘The Damned’. “The only welfare they’re interested in is building bigger detention centres for rockers.”

Threaded throughout the frank discussion of sex, drugs and violence that characterises ‘Generation X’ is a concern that children have become opaque to adult society, and have their own rites, customs and language. “You’d really hate an adult to understand you,” one teenager claims. “That’s the only thing you’ve got over them – the fact that you can mystify and worry them.” Meanwhile a parent complains that “you never have 100 per cent contact with teenage kids these days”.

Jane Deverson and Charles Hamblett’s ‘Generation X’ (1964) detailed emerging postwar youth cultures.

Like the recurring epithet ‘Damned’, the ‘X’ in ‘Generation X’ is part of the stage machinery of the horror film, which was changing rapidly in the science-fiction world of rockets, space travel and atomic weapons: “It was partly X as in the unknown – teenagers were a mystery,” Deverson later explained. “It was also so shocking at the time, like an X film – because the book interviews pulled no punches.”

The X certificate at the time denoted films with restricted adult content, not necessarily sex and violence alone. Among the talk in ‘Generation X’ of coffee bars, pills and parties are references to teenagers becoming “wildly fascinated by witchcraft, black magic, extra-sensory perception, telepathy, astrology and hypnotism”. They also claim to consume large amounts of science fiction. “Teenagers are surrealistic,” one explains. “They can go back and forth in time, and logic and convention don’t hamper their minds.”

‘Generation X’, now more commonly identified by the American appellation ‘baby boomers’, would continue to be studied and defined until late in the 20th century, its subcultures constantly being picked over and revisited. In 1968 John Wyndham returned to the theme of the ‘unearthly child’ with his novel ‘Chocky’. Matthew, an eleven-year-old boy, claims to have an imaginary friend called Chocky living inside his head. The creature is genderless, highly artistic and holds startling views on astrophysics and space travel, all of which are articulated entirely through Matthew.

John Wyndham’s ‘Chocky’ (1964) features a child with an imaginary friend that turns out to be an alien consciousness.

Boy and alien merge so completely that Matthew’s father finds both equally incomprehensible: Chocky’s ideas are hard enough to follow without being entangled in “a morass of Matthew’s favourite, and not very specific, adjectives: sort-of, kind-of, and I-mean”. A growing hierarchy of teachers, doctors, experts and consultants attempt to make sense of Matthew and Chocky. Parenting, Matthew’s mother wryly observes, “must have been a lot more fun before Freud was invented”, while his father darkly mutters that “children just seem to be one phase after another”.

There is talk of witches and devils and how myths and legends make young minds “disposed to accept the improbable without any question”. Ironically it is only after the adults accept Chocky as real that the alien is safely exorcised from the child.

Waiting in the sky

From Meba to Chocky and beyond, the ‘unearthly child’ narrative occupies a relatively short timescale, but its folds and wrinkles run deep. Its development parallels the early years of the Space Race from the Soviets’ Sputnik programme to the Apollo moon landings.

As American astronauts were returning from their last lunar mission in 1972, David Bowie placed the generational divide firmly in outer space with the song ‘Starman’. Children talk late at night on the telephone about the alien presence “waiting in the sky” to meet them. Fear and suspicion are mixed with excitement: one voice warning the other not to tell their father “or he’ll get us locked up in fright”. There are optimistic references to rock music, radio stations and dance, but the Starman still remains waiting at the song’s end.

The alien encounter with youth had already taken place by then, the invasion long underway. The release of ‘Starman’ coincided with the publication of ‘Folk Devils and Moral Panics’, Stanley Cohen’s classic study of the antagonism between youth and society in the early 1960s.

Focusing on the pitched battles occurring between mods and rockers on British beaches, Cohen charts a lack of mutual trust and understanding, only deepened by media reports of teenage violence. He quotes a Brighton editor as describing the gangs roaming the seafront as “something frightening and completely alien… they were visitors from a foreign planet and they should be banished to where they came from”. By the mid-1970s this was easier said than done.

At its most mythic, Cold War youth came from the future: a point underscored by ‘The Tomorrow People’, a Thames Television children’s series that began in April 1973.

As they approach or pass adolescence, certain children in contemporary Britain discover that they have advanced mental powers – a familiar theme by now. The physical and mental crisis suffered by schoolboy Stephen in the first episode suggests something closer to the onset of puberty. Even the TV show’s term for this moment of psychic awakening, “breaking out”, sounds more like a teenage acne attack.

Thanks to a girl called Carol, who is able to teleport from the Tomorrow People’s secret base in an abandoned London Underground station to his hospital bed, Stephen learns that together they mark “the next development of the human race… Homo Superior”. According to series creator Roger Price, the term dated back to a conversation he had with David Bowie at Granada Television studios and references a line from Bowie’s song ‘Oh You Pretty Things’.

Pursued by bikers like those in Losey’s ‘The Damned’, the central characters quickly find themselves in now familiar territory. “I can feel you – right inside my head,” Stephen confides in Carol. Meanwhile Stephen’s teacher complains of his daydreaming and “not trying as hard as he used to”.

‘The Tomorrow People’ (1973–9) featured a cast of teens with special powers, including telepathy and the ability to transport themselves.

The original ‘Tomorrow People’ ran until 1979 and was subsequently updated, generating a US version in 2013. Meanwhile ‘Dr Who’ has continued to be reformatted and reworked, and ‘The Village of the Damned’ was remade in 1995. Even the term ‘Generation X’ was redeployed to designate those born between the early 1960s and the 1980s.

The ‘unearthly child’ has continued to evolve and manifest itself in everything from punk rock to ‘Star Wars’, both of which have their origins in late 1970s pop culture. As a teenager wrote back in 1964: “Every new Generation X has the same problems and they can only be solved by growing up.”

About the author

Ken Hollings

Ken Hollings is a writer, broadcaster and lecturer based in London. His work has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies, and he has presented critically acclaimed programmes for BBC Radio 3 and Radio 4. His books include ‘Destroy All Monsters’, ‘Welcome to Mars’, ‘The Bright Labyrinth’ and ‘The Space Oracle’.