Sleep paralysis was once known by the term ‘night-mare’ and associated with demonic possession. Historic treatments included bloodletting and shaving the head. Science can now explain the disorder, but it is still a frightening experience.

Today we use the term ‘nightmare’ to explain a generally frightening dream or unpleasant experience, but until the late 19th century the term night-mare (hyphen included) was exclusively descriptive of sleep paralysis, a sleep disorder in which the body is temporarily immobilised at the moment of waking or the moment of falling asleep. It is a minor, yet common, body/mind malfunction that upwards of 50% of the population claims to have experienced at least once in their lifetime.

Regular bouts of sleep paralysis can be a symptom of conditions like narcolepsy or PTSD, but sometimes these conditions do not provoke sleep paralysis at all. Random occurrences of sleep paralysis typically stem from periods marked by lack of sleep, medical or anaesthetic error or high levels of stress. The unpredictability of this parasomnia makes it all the more frightening when it happens.

The science behind sleep paralysis

Sleep paralysis is relatively easy to explain and is (generally) not a serious condition. It occurs when brain and body are not in sync during the sleep process. During a ‘normal’ night’s sleep we can expect the brain to dispatch a message to the nervous system that relaxes the muscles; so relaxed are they that they become inactive during sleep, protecting our body from acting out physically while in the state of sleep. As the brain is roused to a waking (hypnopompic) state or as it falls into a sleeping (hypnagogic) state the brain gives the order to end or start the paralysis.

Sleep paralysis occurs when the process happens at the wrong speed; when the brain and body are out of sync. If the brain doesn’t give the order to the muscles, the muscles lay dormant while our mind is stirred to consciousness, giving us the sense of paralysis. As this liminal state persists it activates our limbic system, our centre of emotional reaction, causing fear and panic. If an individual is in the middle of a disturbing dream, this sense of fear is heightened ten-fold because there is usually a hangover that results in visual and auditory hallucination.

Although our contemporary knowledge of neuroscience demystifies sleep paralysis, its explanation does not match the extra-sensory fantastic experience of it. It’s no wonder that throughout history it has been linked to paranormal forces, from demons to aliens.

Riding with the demons

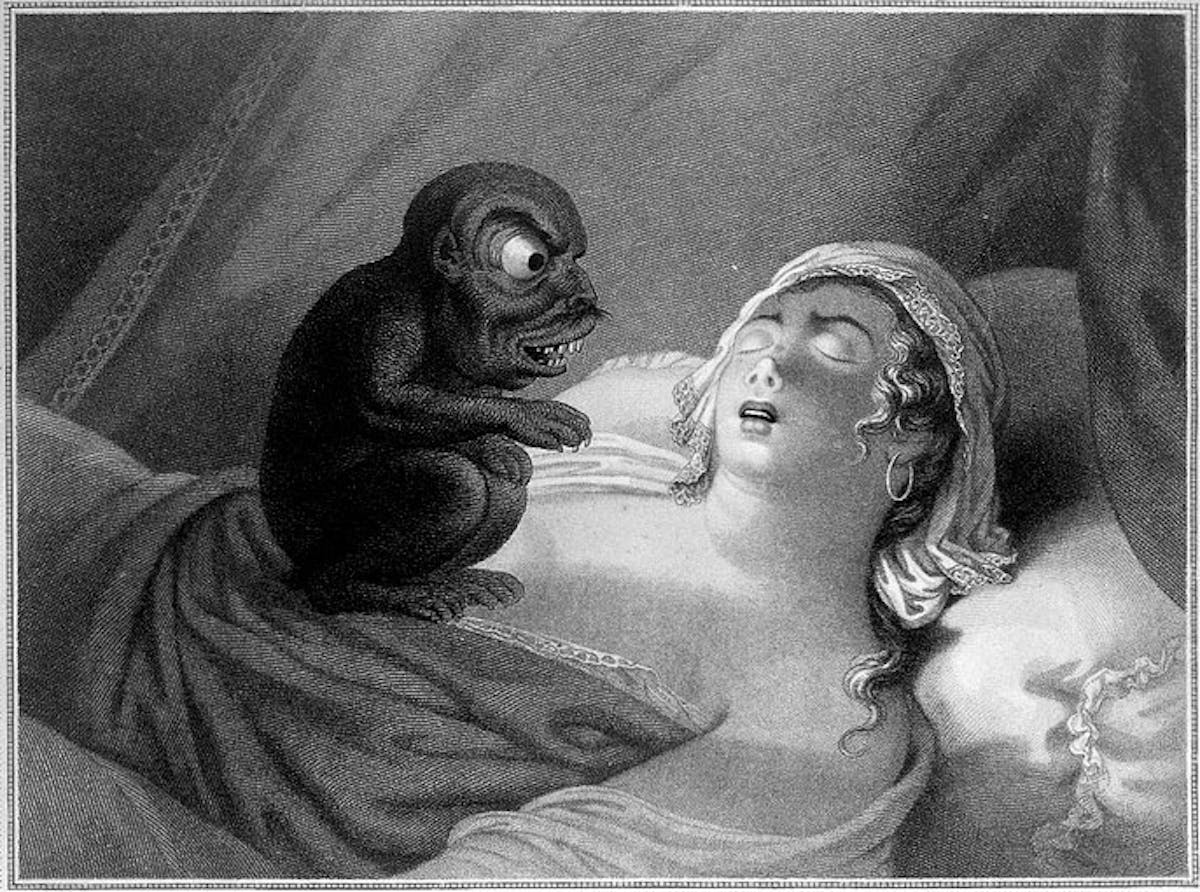

The Western concept of the nightmare is weighted with an accumulation of historical interpretations that emerged from the myth of the incubus. From ancient Mesopotamia (c. 2000 BCE) to the Roman Empire, a demon known as the incubus was responsible for your bad dreams. Originating from the Latin ‘to sit on’, the incubus sat on top of your chest inducing horrifying dreams and physical immobility, making it the first documented explanation of sleep paralysis.

We get our term ‘mare’ from the Old Norse version of the incubus: the mara, which comes from the verb merran or ‘crusher’. Not precisely a demon, the mara is a person with magical attributes who ‘rides’ their victim for the pleasure of pure wickedness. Grendel, the fearsome villain of the Anglo-Saxon tale ‘Beowulf’, is a perfect example of the mara crushing and devouring his prey in the dead of night. In subsequent centuries, the mara is shape-shifted into the Old Hag myth, which Shakespeare appropriates for his epic Queen Mab soliloquy from 'Romeo and Juliet'.

Today, the demon of sleep paralysis has morphed again, taking the form of the alien abduction, playing upon our fear of the unknown universe that surrounds us.

Engraving of a young woman asleep with a devil sitting on her chest, symbolising her nightmare.

Nightmarish treatment

There is currently no prescribed treatment for sleep paralysis, but doctors suggest that making your sleep schedule regular can decrease these incidents of parasomnia. However, the earliest treatments for incubus and nightmares were sometimes as frightening as the experience itself. The first mention of a treatment for sleep paralysis was noted by Byzantine physician Paulus Aegineta in the 7th century. In one of his seven books on the history of medicine, Paulus explains the most common way to treat the complaint was through “bleeding, drastic purgatives and friction of the extremities.” Paulus placed focus on the head as the source of the problem, suggesting that if the above treatment did not work, the cupping and scarification of the throat, a restricted diet and shaving of the head would.

Tenth-century Persian polymath Akhawayni Bokhari was the first to completely disassociate the night-mare from demonic possession in his ‘Learner’s Guide to Medicine’ (Hidayat al-Muta`allemin fi al-Tibb), making it a solely physical problem. A subscriber to the ancient theory of humorism, Akhawayni believed night-mare was caused by vapours of phlegm ascending from the stomach to suffocate the brain during sleep. Although his theory was different, his treatment was no different from his predecessors: bloodletting.

In the Christian era, sleep paralysis was akin to demonic possession and those afflicted were treated with prayers and exorcism. But as the Age of Enlightenment took hold, demons diminished and medical care moved towards our modern understandings of empirical observation, changing the treatment of sleep paralysis.

Page 71 from ‘An essay on the incubus, or night-mare’ (1753), by John Bond.

John Bond’s 1753 ‘An essay on the incubus, or night-mare’ prescribes poking the afflicted with a pin or shaking them to a wakeful state, which is perhaps the most frightening thing you could do to someone temporarily immobilised in a hallucinatory state (other than bloodletting, of course).

Creative potential

We know what sleep paralysis is and we know how to treat it, but it still scares us. What is most fascinating is that sleep paralysis occurs when the mind has complete control: the body’s senses are restricted and the imagination has almost complete reign. If we orient ourselves through touch, fine-tuned hearing and clear sight, what happens when all of those things are at the mercy of the misfiring of our brain?

Sleep paralysis is the immediate experience of the depths of uncontrolled consciousness. It allows the mind to stretch beyond the logical frames of existence, blurring the boundaries of waking and dreaming life, making it a valuable tool for artists throughout the centuries. The experience of sleep paralysis allows us to understand the power of unbridled imagination (‘mare’ pun intended). This is the very reason that the study of sleep paralysis is also the study of cultural storytelling. From the novel to visual art, from theatre to music, sleep paralysis has been used to evoke the drama of an unfettered imagination and the dark recesses of the mind.

The experience of sleep paralysis not only alters the consciousness of an individual at the moment of waking or descending into sleep, but it has made a lasting impression on our perception of reality in Western culture.

About the author

Sarah Jaffray

Sarah Jaffray is an art historian and Visitor Experience Assistant at Wellcome Collection.