Collective Healing Through Confrontation in Safety by Janice Li

We are only trapped in history when history is trapped in us.

The Healing Pavilion

Having spent decades living in Buddhist monasteries and other spiritual communities, Ndiritu recently began exploring the idea of architecture as ‘spiritual technology’ in her work. She delves into the power of interior spaces to facilitate the healing of both the individual and the mass.

Two tapestries are hung within a site-specific structure, inspired by Zen Buddhist temples in Japan. The installation is designed to reactivate the museum as a space to encounter, contemplate, ask questions, exchange, listen, share and meditate.

The sanctuary-like pavilion is lined with walnut panels from the recently deinstalled and controversial ‘Medicine Man’ gallery of objects from Sir Henry Wellcome’s collection. Rather than explicitly investigating the legal restitution process for contested collection objects, this structure physically and spiritually transforms the gallery into a safe, meditative space for quiet contemplation. At the same time, it welcomes visitors to encounter the large-scale tapestries that present a traumatic, unresolved colonial past of museum practices. Through this work, Ndiritu asks how we might energetically and architecturally reinvent the role of contemporary museums and reshape these institutional spaces.

The Twin Tapestries

Photography was not only a witness and document of the colonial regime, but also its tool and accomplice.

Two archival images of group portraits from Wellcome Collection, London, and the Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin, are enlarged and woven into large-scale tapestries, forming ‘The Twin Tapestries: Repair (1915) and Restitution (1973)’. Together the pair reveals violent pasts at the foundation of Western museology and reflects attitudes and practices towards African collections in many European museums.

Arranged portraits are about power. Albeit bloodless, the brutality these images carry can still be disturbing and paralysing to encounter. Ndiritu’s presentation of these images is not accusatory, nor is she critiquing the past from a contemporary moral high ground. Rather, the work is an attempt to open up dialogues in order to relate across time and understand how cultures have been alienated and othered under an imperialist system. Ndiritu’s installation is not intended to materialise the extremity of past suffering. Mindful of how reproduction of such images might risk perpetuating dominant colonial narratives, her work acts as a medium to interrogate and comprehend them.

Repair (1915)

One of the two tapestries is based on a photograph from Wellcome Collection’s archive, depicting junior members of staff of Henry Wellcome’s private Historical Medical Museum in 1915. They are posing with human remains and collection objects from the Global South, including masks and skulls. The identities of a few male sitters are known but not those of the female staff, as women workers’ names were rarely recorded. The objects vary widely, as do the ways in which they are being held – from authoritative and possessive, to affectionate and protective. For Ndiritu, the yellow-threaded border symbolises both positive associations with sunshine and courage, and negative ones with danger and toxicity.

The sitting was staged in a gallery titled, ‘Hall of Primitive Medicine’. It displayed predominantly non-European objects categorised based on theories that othered, exoticised and marginalised the cultures they described. Titles of the gallery sections are exemplary of such biases, including ‘Secret Society Masks, etc.’, ‘Primitive Surgery’, ‘Pathological Objects Endowed with Magic’, ‘African Charms’, ‘Magic Egypt’ and ‘Folklore Palestine’. After Henry Wellcome’s death in 1936, around 90 per cent of his private museum collection was gifted or transferred by his trustees to other institutions across the world – as they were then considered less relevant to a Eurocentric history of medicine. As a result, only a small number of objects in the image have been successfully identified.

Please refer to ‘The colonial roots of our collections’, and our response on our website for more information on our commitment to confront the history of our collections.

Restitution (1973)

The image forming the other half of ‘The Twin Tapestries’ is based on a photograph taken nearly six decades after that of ‘Repair (1915)’ and reflects a different attitude towards ethnological collection objects. The theatrical group portrait was taken in 1973 at the Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin. It is believed to be an informal record of museum staff posing on a display plinth one day after work.

Ndiritu chooses to surround the tapestry with pink threads to draw out the apparent sense of good fortune and open-mindedness; at the same time it alludes to passivity and to the pink triangle that was used to identify ‘homosexual’ prisoners in Nazi Germany. First coined in German in 1868, ‘homosexual’ was the terminology used both by the Nazis and gay people under the Third Reich. It is an outdated medical term now widely recognised as having pathologising connotations.

Four museum staff are captured sitting and leaning on a royal throne from the Kingdom of Bamum in Cameroon, which had been under German colonial rule from 1884 to 1916. The Mandu Yenu throne was an object that demanded respect and signified power in its original context. The posers’ playful attitude reveals a shocking behind-the-scenes relationship between museum workers and ethnological collections that is not usually seen in public. The throne is currently on display at the Humboldt Forum in Berlin. The contested history of how it arrived in Berlin and where it shall stay in future are still under discussion in Germany.

The artist had to digitally alter the faces of those depicted in the original photograph to shift attention away from the identities of those who are still living.

By putting the focus directly on the interaction between the staff and the objects, Ndiritu asks instead what restitution for a history such as this might look like. Less a forced reconciliation between traumatised individuals and those responsible, she suggests, but one achieved within society through an understanding of its difficult pasts and the enormity of collective violence.

In pictures

1 of 3

A view inside the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum, which was situated on Wigmore Street in London. The original caption describes this space as the ‘Hall of Primitive Medicine’.

2 of 3

Another view inside the Wellcome Historical Medical Museum. The original caption describes this display as “a head-hunter’s hut, southeast New Guinea”.

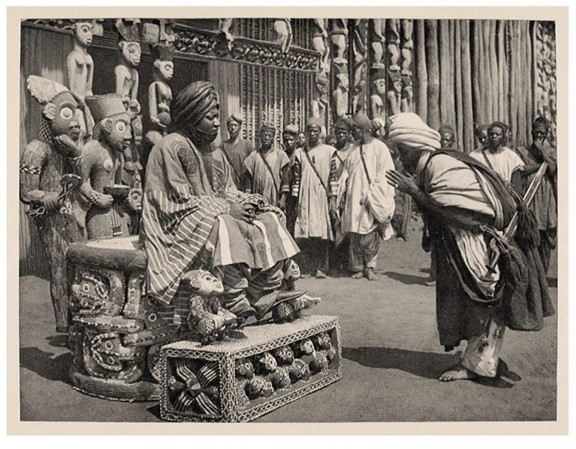

Photograph showing Bamum fon (King) Njoya sitting on his Mandu Yenu throne in 1912, Marie-Pauline Thorbecke. Source: Im Hochland von Mittel-Kamerun, Vol. I, 1914.

3 of 3

This photograph shows Bamum fon (King) Njoya sitting on his Mandu Yenu throne in 1912.

To Heal

Choosing the medium of tapestry to present these archival images, Ndiritu gives the photographs material as well as symbolic weight. For her, “the honest weight of tapestry... materially and viscerally embodies the raw residue of history”.

However, such heaviness is often challenging to bear, even with the most earnest intention. How might we relate to those involved? How can we navigate the contemporary world without feeling ensnared in the histories we are tied to through ancestry and kinship?

Studies from neurobiology and psychotherapy might shed light on how we can connect systemic suppressions and collective trauma through an understanding of personal healing. Intergenerational transmission of trauma is influenced by cultural, psychological and socioeconomic factors, but trauma can also induce epigenetic change (how genes are expressed) in a person’s DNA. Such neurobiological alterations can be passed from one generation to the next, causing physical, psychological and social challenges even for those who had not experienced the trauma first-hand.

Epigenetics is a field of research that is still young and contested, but what we do know now is that these changes are reversible. Reconsolidating emotional connection to traumatic events by confronting the source of trauma in a safe, compassionately held space is fundamental to the healing process. In a collective sense, healing – through repair and restitution – is possible.

In reference to the title of the tapestries, the artist explains, “Repair and Restitution are two sides of the same coin”. To reconcile requires interpersonal restoration as much as legal, institutional actions. She aims to tease out such interwoven healing from a heavy, complex history, still entangled with problematic systems we operate within today.

Ndiritu states, “the installation is about the history of European curating in the 20th century – of where we got to from 1915 until now. And the importance of that trajectory being the lessons we still have not learnt yet.” Suppressions of institutional memory that have allowed only surface-level operation are dysfunctional and we are at a point in history when we can no longer play along.

Repair and restitution are merely part of the process. The artist’s aim is not for a literal return to a certain state of the past, but to transform our relationship to history for a different future. In Ndiritu’s own words, her works serve as “an instigator and participant in a new wave of positive development in human consciousness currently taking place… to enliven the Museum once again back into action so that it can claim its proper place – as a cultural space in which new advancements in art, audience participation and art education can affect wider society and life for the good of all beings”.

‘The Healing Pavilion’ gives rise to an opportunity to embrace and exercise both our rational and intuitive capacities; to see the potential to drive change when we have the safe, contemplative space to become attuned to our non-rational, deeply embodied intelligence.

Resonating with James Baldwin’s wisdom, Ndiritu’s work courageously takes on his vision: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

References

The opening quote is taken from the film, ‘Logic Paralyzes the Heart’ (2021). It is an adaptation of James Baldwin’s statement in ’Notes of a Native Son’ (1955): “People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.”

The second pull quote is taken from page 144 of ‘Everything Passes Except the Past’ (Brussels and London: Goethe-Institut and Sternberg Press, 2021).

Other works referenced include:

Bessel van der Kolk, ‘The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma’ (New York: Viking Penguin, 2014).

N Youssef, L Lockwood, S Su, G Hao, B Rutten, ‘The effects of trauma, with or without PTSD, on the transgenerational DNA methylation alterations in human offsprings’. Brain Sci. 2018;8(5):83.

Grace Ndiritu, ‘Healing the Museum’ in ‘Everything Passes Except the Past’.

James Baldwin, New York Times, 14 January 1962.

About the author

Janice Li

Janice Li is a curator at Wellcome Collection, and curator of the exhibition ‘The Cult of Beauty’. She has curated exhibitions and commissioned design projects internationally and is a founding member of the Hong Kong Design History Network. She co-curated the Hong Kong Pavilion, ‘Sandtable’, at the London Design Biennale 2021. Janice speaks and lectures regularly on curatorial, research and sustainable design practices and is currently an associate lecturer on the MA Design for Social Innovation and Sustainable Futures at the London College of Communications.