Today’s attitudes towards what we now term self-harm are very different from those of the early modern period. Find out how incidents of non-suicidal self-injury were filtered through plays, poems and songs, and what these tales tell us of the spectrum of anger or emotional distress experienced by their subjects.

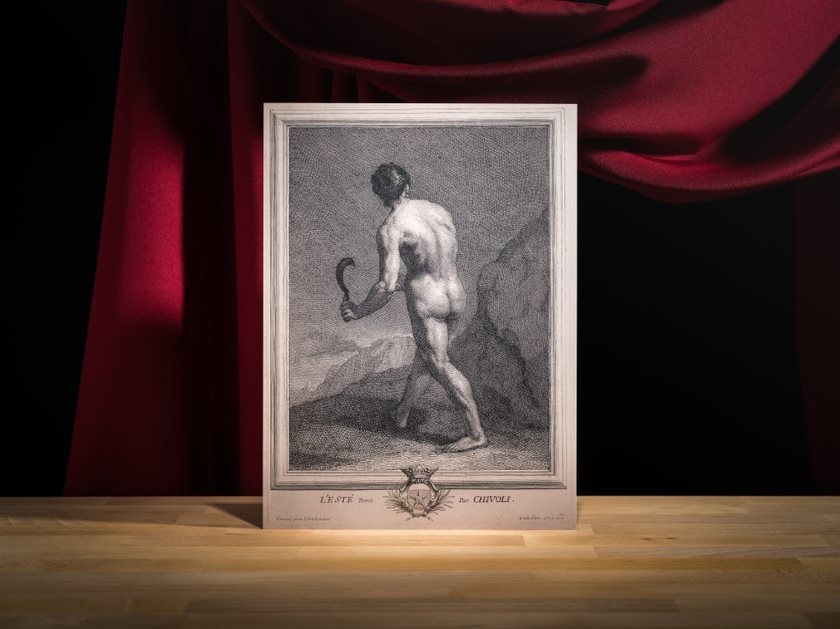

In 1718 the writer of a book about eunuchs recounted a story that had been doing the rounds of medical books and travel writing for several decades. The story concerned a peasant whose jealous wife kept nagging him, accusing him of infidelity. One day, when his wife was “continually tormenting him”, the book tells us “he made no more ado, but immediately, with his scythe that he then had in his hand, whipt off those parts which gave her so much umbrage, and without any more ceremony threw them in the good woman's face”.

To a modern listener, this grisly story is a troubling account of self-harm, undertaken by a deeply disturbed individual. However, the author of the book took a more pragmatic view, observing that some men would simply rather “lose the advantages those parts bring with them” than suffer the “inconveniencies” they could also cause. Cutting off one’s own testicles was certainly an extreme reaction to marital strife, but it didn’t mean the man in question was mentally unwell.

Instead, he was just one of many people in the period from 1550 to 1750 who hurt themselves by cutting or stabbing themselves, scratching their skin, tearing their hair out or even biting off their own tongues. These people appeared across a range of texts, from comedic songs to serious drama.

Self-injury was frequently depicted in plays by the period’s most famous authors, from Christopher Marlowe’s ‘Tamburlaine the Great’ to Shakespeare’s ‘Julius Caesar’, as well as popular books of natural philosophy and anthropology, such as John Bulwer’s ‘Anthropometamorphosis’. But if it wasn’t a symptom of illness, how was self-injury understood?

“Self-injury was frequently depicted in plays by the period’s most famous authors, from Christopher Marlowe’s ‘Tamburlaine the Great’ to Shakespeare’s ‘Julius Caesar’.”

Sin, sickness and protest

One reason that tales of self-injury were so widely scattered between different kinds of text was that hurting oneself was not a defined behaviour in the same way that it is today. Suicide had long been a topic of heated discussion, and it was firmly designated as sinful by both Church and state. Those who ended their own lives could be buried outside Church grounds, and have their worldly goods seized by the state, leaving their families destitute.

However, self-injury was far less discussed. Though some scholars – including the poet John Donne – insisted that self-injury was “in conscience the same sinne” as suicide, there was no law against it. Indeed, there was no term such as ‘self-harm’ or ‘self-injury’ to describe these sorts of acts. Individual people might castrate, stab, or otherwise hurt themselves, but they did not belong to a discrete group.

This poses a challenge for historians researching this topic, who are left with the task of tracking down isolated accounts of self-injury in texts hundreds of years old. However, for early modern people, lack of terminology was vital to the cultural impact of stories about self-injury, because it meant that such events could be interpreted in numerous different ways.

In 21st-century Western society, self-injury is reliably designated as a medical issue. “Non-suicidal self-injury” (NSSI) was first included in the 2013 edition of the American Medical Association’s ‘Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders’ (DSM), having previously appeared in that text as a symptom of borderline personality disorder. It also appears in the World Health Organization’s ‘International Classification of Diseases’.

In early modern texts, however, self-injury was presented rather differently. Some people certainly injured themselves as a result of mental illness. In a 1689 treatise on dreams and visions, for instance, the English self-help author Thomas Tryon informed his readers that in a frenzy, “man can without Dread and Fear lay violent hands on himself… this is madness of the highest degree”. Others, though, turned to self-injury as a way to prove a point or protest an injustice.

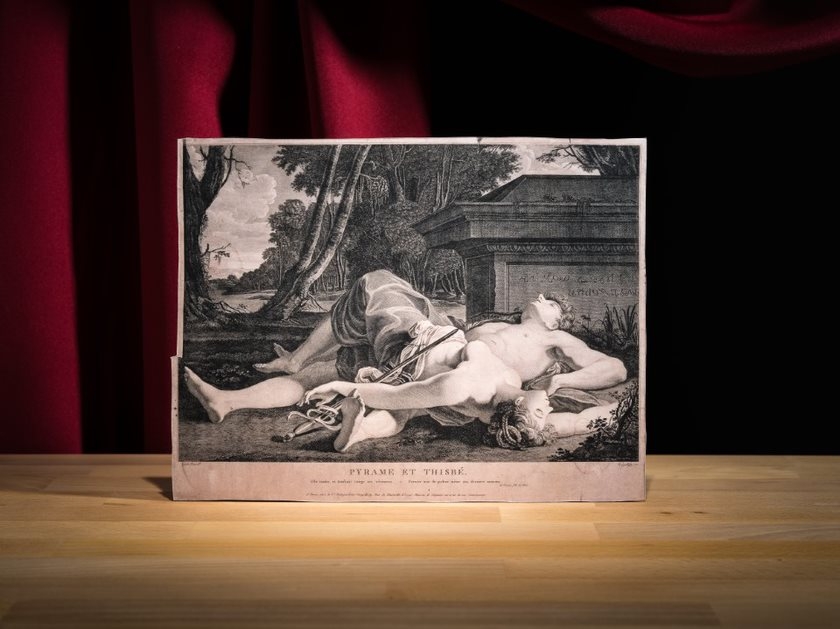

“Portia, Brutus’s wife, turns to self-injury when she is frustrated by her husband’s refusal to divulge what is troubling him.”

Self-injury and self-expression

For early modern people, the idea that self-injury could be an effective means of persuasion or self-expression was popularised in the theatres of the late 16th and early 17th centuries. In ‘Julius Caesar’, for example, the character of Portia, Brutus’s wife, turns to self-injury when she is frustrated by her husband’s refusal to divulge what is troubling him. Though she is a woman, she insists, she is still capable of keeping secrets:

Tell me your counsels; I will not disclose ’em.

I have made strong proof of my constancy,

Giving myself a voluntary wound

Here in the thigh. Can I bear that with patience,

And not my husband’s secrets?

For Portia, wounding herself provides evidence of her fortitude that goes beyond words. Like many of his fellow playwrights, Shakespeare was fascinated by the ancient art of rhetoric, but he also questioned whether the body could ‘speak’ – perhaps in a way that was different from verbal communication, but just as effective.

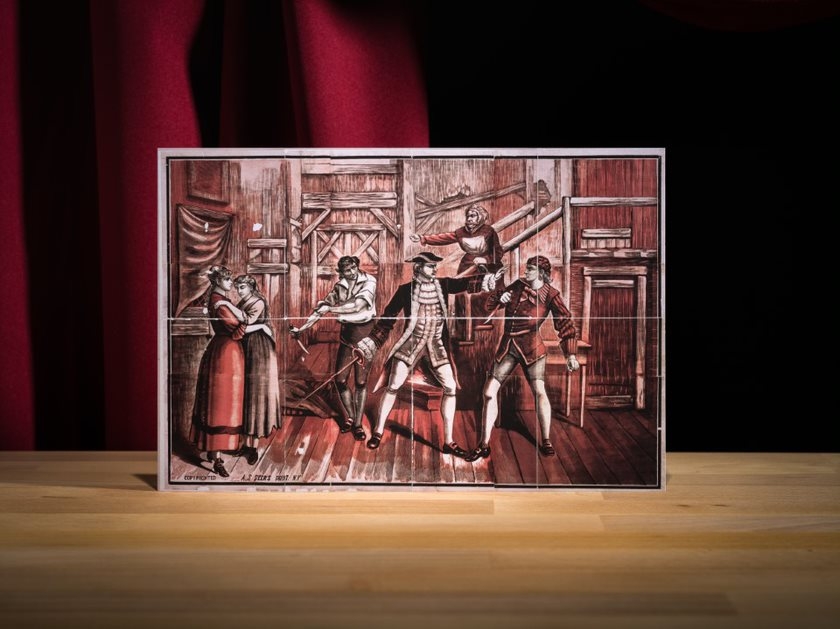

The theme of speaking with the body took on a gory twist in Thomas Kyd’s ‘The Spanish Tragedy’, written in around 1590. Kyd’s violent play was incredibly popular in its time, combining a labyrinthine plot with ample helpings of blood and guts.

In the play’s bloodiest scene, the hero, Hieronimo, decides to take revenge on the men who have murdered his son by staging a play in which he replaces the fake weapons with real ones, so that the murderers are stabbed to death in front of their courtly audience.

When Hieronimo’s crime becomes clear, the king orders him to be seized and tortured. However, rather than divulging the details of his plot, Hieronimo bites out his own tongue:

…never shalt thou force me to reveal

The thing which I have vowed inviolate.

And therefore, in despite of all thy threats,

Pleased with their deaths, and eased with their revenge,

First take my tongue, and afterwards my heart.

[He bites out his tongue]

Like Portia’s self-stabbing, Hieronimo’s tongue-biting recalled stories about the Stoics, a sect of ancient philosophers whose translated works became extremely popular with 16th-century readers (some scholars argue that Stoic works were the most read secular books at this time).

“Thomas Kyd’s violent play ’The Spanish Tragedy’ was incredibly popular in its time, combining a labyrinthine plot with ample helpings of blood and guts.”

Stoics held that maintaining one’s sense of virtue was the most important thing in life. While they admitted that pain existed, they believed that in essence, it was a neutral event, and it was only our desire not to experience pain that made it seem bad. If one could abandon that desire, then true self-mastery could be achieved, and one would never be cowed by personal misfortunes or tyrannical regimes.

From stage to song

The men and women who wounded themselves on the Renaissance stage were often presented as noble and heroic. However, this was not always the case in other accounts of self-injury.

As the 17th century went on, stories about self-injury started to appear less often in plays and more often in ballads (verses set to popular tunes) and medical texts. The people who appeared in these kinds of texts were nearly always men who had cut off their own testicles, like the unfortunate husband in the story above.

For instance, a ballad called ‘The Quaker’s Wife’s Lamentation’ tells the story of a woman who discovers that her husband has gelded himself. With plentiful helpings of bawdy innuendo, the Quaker’s wife complains:

Dear Husband you have done me wrong,

For Poets will put us in a Song,

You might as well have cut off all,

As leave behind a thing so small,

And thus to break your Wedlock Band,

To leave a Thing that cannot stand.

Ballads about men who castrated themselves frequently found black comedy in the events they described. In another song called ‘The Miserable Maulster’, a man cuts off his testicles because he can’t help cuckolding every other man in town. Rather than praising his decision, the women of the town relentlessly mock him:

“Ballads about men who castrated themselves frequently found black comedy in the events they described.”

Oh! the scoffs of the woman this Maulster does dread,

For they tell him ’twere better he’d Cut off his head.

Even in medical books, self-gelding was treated as a curiosity rather than a serious problem. In 1678, for example, the surgeon John Browne reported two separate incidents in which men from his home town of Norwich had tried to castrate themselves. While modern readers would view this as a grave emergency, Browne reported quite calmly that the men were stitched up and were now “in very good health”.

Such reports might have been jovial, but they always took care to include something about the reasons for men’s self-injury. Men’s explanations for self-gelding included punishing themselves for adultery, punishing their wives for adultery (actual or suspected), preventing themselves fathering children they couldn’t afford, revenge on nagging wives, or disappointment about being unable to perform sexually.

In each case, they showed how men felt pressure to live up to the dominant patriarchal ideal. If one couldn’t achieve mastery over one’s family and one’s own body, then self-gelding was a way to literalise the feelings of emasculation that followed.

As ideas about medicine and the emotions changed in the 18th century, representations of self-wounding shifted once again. Ballads about self-castration gave way to novels in which lovelorn characters might injure themselves as a demonstration of their emotional sensitivity or ‘sensibility’. Sensibility was a laudable quality in the right amounts, but it could easily spill over into melancholy and despair.

“If one couldn’t achieve mastery over one’s family and one’s own body, then self-gelding was a way to literalise the feelings of emasculation that followed.”

The boundaries between self-injury as a communicative strategy and as a sign of madness were dissolving, and by the early 19th century, self-injury had begun to be regarded as a symptom of mental illness.

Modern contexts

Early modern tales of self-wounding may seem a far cry from 21st-century thinking about non-suicidal self-injury. Nonetheless, it can help us to think about what self-injury means, and how people who self-injure are treated by society.

The DSM defines NSSI as practices that are “not socially sanctioned”, but what is socially acceptable changes radically over time. In the last century, tattoos and piercings, both of which temporarily damage the skin, have become normalised. However, more extreme forms of body modification, such as tongue splitting and branding, still tread the line between self-expression and self-injury.

Like Hieronimo’s tongue-biting, forms of self-injury such as self-immolation may be used as a means of political resistance, without being considered pathological. Considering the changing uses of self-injury therefore encourages us to look closely at how we decide when self-injury should be viewed as a symptom of mental illness that requires medical treatment, and take seriously the use of self-injury as a protest against social or political injustice.

“Early modern writers’ understanding of self-injury was radically different from our own, and may seem misguided or downright dangerous.”

The stories above also show that early modern people understood the impact of social pressures in provoking self-injury, especially among men. Though men enjoyed greater legal and social status in the 17th century, they were also subject to strict social codes, and self-injury was presented as the direct result of men finding themselves unable to live up to those demands. Seventeenth-century authors’ awareness of this conundrum – however jokingly they might present it – is a stark contrast to modern representations of self-injury.

Though recent studies show that men and women are roughly equally likely to engage in non-suicidal self-injury, it has long been considered to primarily affect women. This bias is reflected in much smaller numbers of men seeking treatment for NSSI.

Transgender people are particularly likely to engage in self-injury, with some studies showing that 40 per cent of transgender people had self-injured at some point in their lives. Overall, research shows that the stigma surrounding self-injury deters many people from seeking help.

Early modern writers’ understanding of self-injury was radically different from our own, and may seem misguided or downright dangerous. However, these authors recognised the importance of social pressures in creating this phenomenon, and the blurred lines that existed between self-expression and self-harm.

Unable to search for answers inside the brains of people who hurt themselves, they focused on the things they could see – the cultural and political systems that made self-injury the best way for some people to give vent to their frustration, anger or grief. This connection between mental health and social wellbeing remains an essential part of understanding NSSI for both doctors and patients.

About the contributors

Alanna Skuse

Alanna Skuse is a Wellcome Trust lecturer in English Literature at the University of Reading, UK. Her work focuses on how people of the 16th and 17th centuries thought about medicine and the body, and she has published two books – ‘Constructions of Cancer in Early Modern England’ and ‘Surgery and Selfhood in Early Modern England’. Her current research project focuses on perceptions of self-injury in the period 1580–1740.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.