Blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile: the body’s four humours were believed to control your personality in Shakespeare’s day and influenced the way the Bard created some of his most famous characters.

Shakespeare and the four humours

Words by Nelly Ekströmaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Article

Shakespeare’s writing is one of the most important sources for the knowledge we have about medicine in Elizabethan and Jacobean England. His works contains a lot of information on the contemporary medical practices of the time, but they also show the social history of medicine: how medicine formed a part of people’s lives and thoughts.

What are the four humours?

In Shakespeare’s time, the understanding of medicine and the human body was based on the theory of the four bodily humours. This idea dates back to ancient Greece, where the body was seen more or less as a shell containing four different humours, or fluids: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. The humours affect your whole being, from your health and feelings to your looks and actions.

The key to good health (and being a good person) is to keep your humours in balance. However, everyone has a natural excess of one of the humours, which is what makes us all look unique and behave differently.

If blood dominates, you will have a sanguine temperament; yellow bile makes you choleric; black bile melancholic; and phlegm leads you to being phlegmatic.

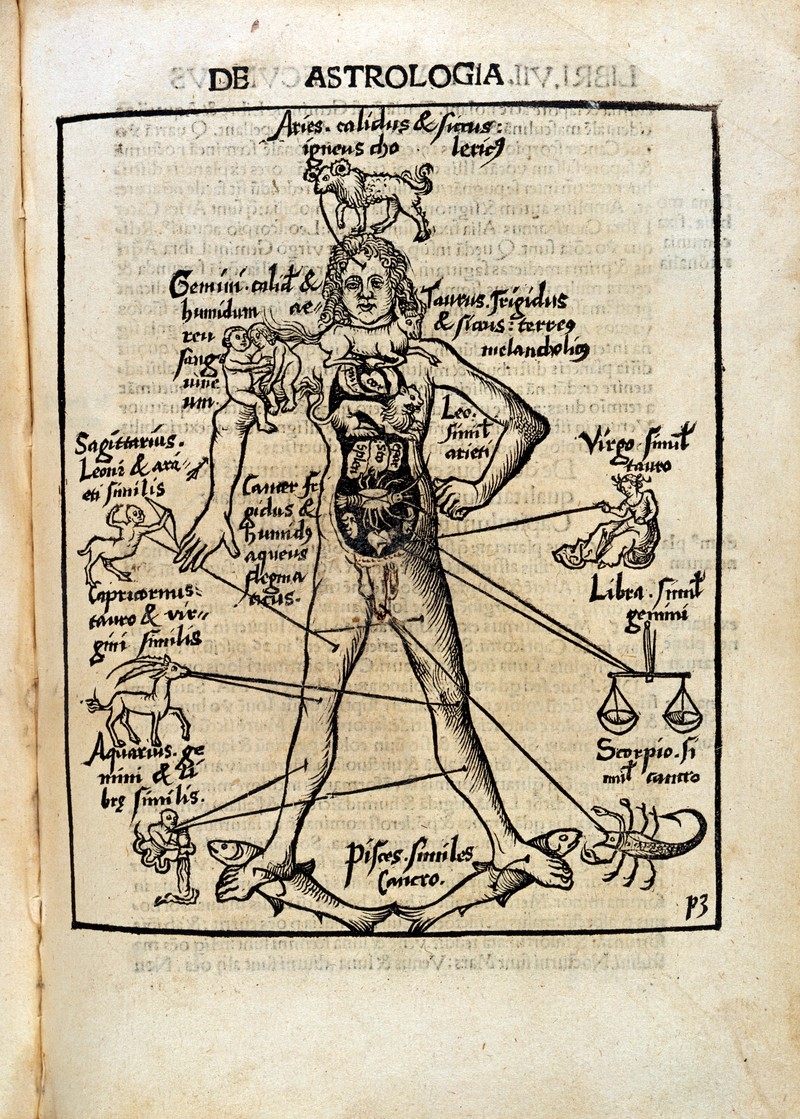

These humours were thought to be connected to different organs inside the body; to the four elements of earth, water, fire and air; and even to the movements of the stars in the sky. Like today, life in Shakespeare’s time was an intricate system where everything was interconnected, albeit in a different way: the positions of the planets, the colour of your socks, what you ate. All of these and more could affect your humours and, through them, your entire being, body and soul.

A 14th century astrological man.

Henry IV and the theory of humorism

One play really stands out when it comes to the subject of humours. In ‘Henry IV’, parts one and two, there are four main characters, one of each temperament. And they all have roughly the same number of lines.

So the play itself is very close to the ideal humoral balance. King Henry IV himself is melancholic, Prince Hal sanguine, Sir Harry Hotspur choleric and the knight Sir John Falstaff is phlegmatic.

Jack Falstaff is fat, lazy, cowardly, dishonest and sentimental, but the audience loved him despite all his faults. He became so popular that Shakespeare later wrote him his own play, ‘The Merry Wives of Windsor’.

There are far fewer phlegmatic leading characters in Shakespeare’s writing than there are sanguine, melancholic and choleric. Besides Falstaff, who has the largest number of lines in ‘Henry IV’, they usually function in the subplot of the comedies, like the duos Sir Andrew Aguecheek and Sir Toby Belch in ‘Twelfth Night’ or Stephano and Trinculo in ‘The Tempest’. In tragedies they may appear in short scenes of comic relief, like the porter in ‘Macbeth’ who messes things up by being drunk on duty.

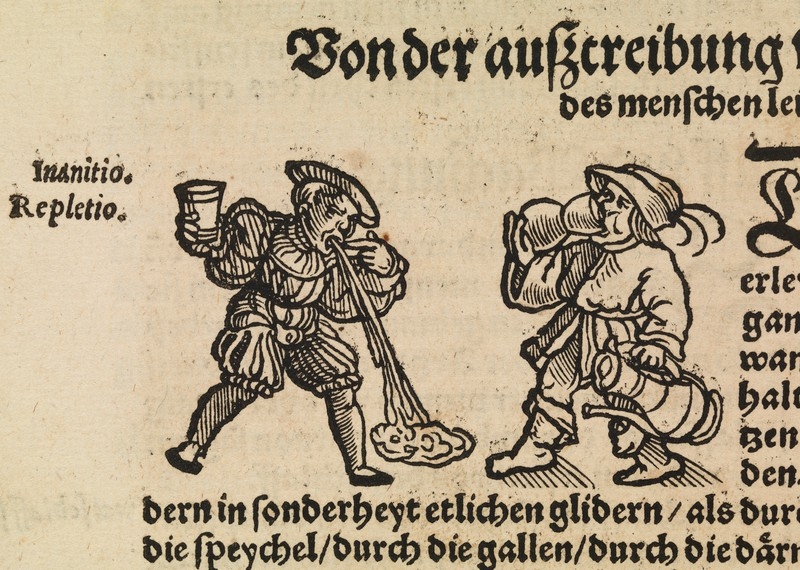

Woodcut of two men drinking, over-consuming and vomiting.

Too much phlegm

All the temperaments have their good and bad sides. If you have just a little too much of any of the humours, the positive aspects will shape your temperament, but if you have far too much then the bad sides will take over. Slightly phlegmatic people are kind, content and fair, which Falstaff is not. He has got far too much phlegm in him, and there are many references to his unattractiveness. This is how Prince Hal greets him early on:

“Thou art so fat-witted, with drinking of old sac, and unbuttoning thee after supper, and sleeping upon benches after noon, that thou hast forgotten to demand that truly which thou wouldst truly know. What a devil hast thou to do with the time of the day? Unless hours were cups of sack, and minutes capons, and clocks the tongues of bawds, and dials the signs of leaping houses, and the blessed sun himself a fair hot wench in flame-coloured taffeta, I see no reason why thou shouldst be so superfluous to demand the time of day.”

Falstaff imagined by artist Eduard von Grützner, 1906.

At the beginning of the play, Falstaff and Prince Hal are great friends. The phlegmatic and sanguine temperaments have a lot in common. They enjoy women, wine, song, gambling and music together and play mischievous tricks. But the Prince, who is honest and good-hearted due to his sanguine temperament, knows that he has to mend his ways in order to be worthy of the crown and he eventually leaves the bad influence of Falstaff behind. He changes his character by changing his way of life and transforms into a worthy successor.

Having an excess of one humour could be a bit of a vicious cycle: it both causes and is caused by your behaviour. Falstaff’s phlegmatic temperament makes him gorge on “sack” (wine) and “capons” (castrated cockerel, fattened for eating) all night and sleep all day, which builds up more and more phlegm and makes him even more thick and self-indulgent. What he should be doing is trying to restore the balance by switching to a warming and drying diet and engaging in warming and drying activities.

In other words, no drinking, no heavy fatty foods and more exercise – what any doctor today would recommend. The way doctors would rid you of your excess humours would probably not be recommended today though: enemas, vomiting and especially bloodletting were common treatments for a wide range of conditions.

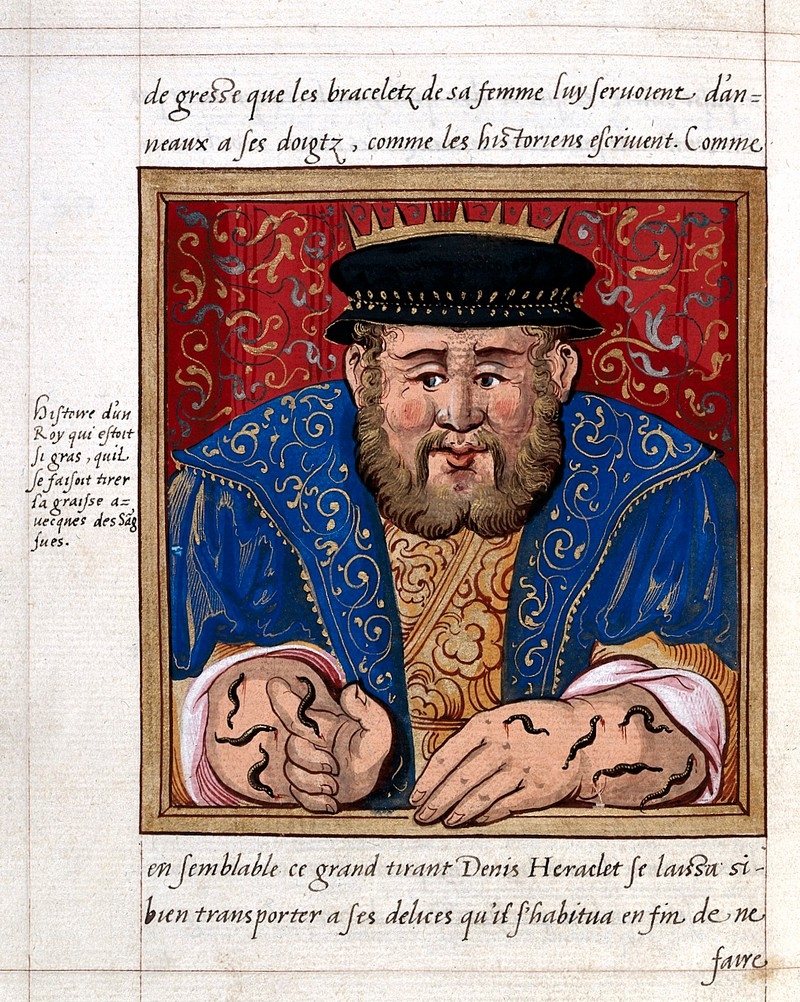

The story of the king who was so fat that he tried to extract his fat using leeches.

Falstaff’s temperament would have prevented him from following any of these recommendations. He’d probably agree with fellow phlegmatic Sir Toby Belch:

“I am a great eater of beef, and I believe that does harm to my wit.”

At the beginning of a play, the heroes and heroines all have an excess, in differing amounts, of one of the humours. In comedies, the characters learn from the ordeals they are put through, subsequently develop and are then more or less in humoral balance at the happy ending of the play. In tragedies, the characters usually start out with a normal excess of their temperamental humour, but thru their actions and reactions their excess is built up, leading to more and more extreme behaviour until all hope of restoring balance is lost.

About the author

Nelly Ekström

Nelly Ekström is a Visitor Experience Assistant, bringing the galleries and exhibitions to life.