Intriguing photographs from sexologists’ archives suggest they could have helped people explore their gender identity and sexuality. Dr Jana Funke reflects on her experiences of discussing sexology and photography with visitors at Wellcome’s Institute of Sexology exhibition.

In 1919, German-Jewish sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld (1869–1935) opened his Institute of Sexual Research in Berlin. In addition to operating as a clinic, the Institute housed an archive and library, and offered educational services to members of the public. Among Hirschfeld’s vast collection were hundreds of photographs, some of which were exhibited at the Institute.

To me, Wellcome Collection’s The Institute of Sexology exhibition was a bit of an homage to Hirschfeld’s Institute and so I was keen to see how 21st-century visitors might respond to such photographs. I had the opportunity to find out when I spent three afternoons at the exhibition talking to visitors about sexology and photography.

Dr Jana Funke discusses sexology and photography at the Institute of Sexology exhibition.

To prepare, I met with the organisers and curators over the summer of 2014. Lesley Hall, a senior archivist at the Wellcome Library, was kind enough to show us some of the original photographs and postcards found among the papers of German-Austrian sexologist Richard von Krafft-Ebing (1840–1902). The Wellcome Library’s holdings also include many sexological publications and so we got a chance to look at Hirschfeld’s medical textbook ‘Sexualpathologie’ [‘Sexual Pathology’], published in Germany in 1918, which includes photographic images. In the end, we selected a number of photographs from the Krafft-Ebing archive and Hirschfeld’s textbook to be reproduced for the event.

In pictures

A man in corset and stockings.

A man seated, wearing a corset and holding a whip.

A man wearing ladies’ shoes and stockings.

A man in a ballet-style pose.

I was keen to find out what visitors made of these images, especially because some of them are rather mysterious and there is so much we do not know. The studio shots of a man posing in women’s clothing, for instance, were found randomly among Krafft-Ebing’s papers after the sexologist’s death. The photographs must have been taken in the second half of the 19th century, but they were never published or discussed in writing. Visitors immediately noted the elaborate studio setting and the careful selection of props and costumes – we talked a lot about the beautiful shoes in particular!

MORE: The Transvengers travel back in time to challenge Hirschfield and other key sexologists

Looking at large-scale reproductions of the images, we also noticed how the photographs had been manipulated: if you look closely, you can see what can best be described as 19th-century Photoshopping. In several of the images, the contours of the hips, bottom and feet are redefined, so as to make the body appear more ‘feminine’.

What do we make of these images? It is impossible to know who the man in these pictures was and we can only speculate as to why they were taken in the first place. Given that cross-dressing was heavily regulated and even criminalised in many European countries at the time, visitors discussed whether these photographs offered the subject an opportunity to try out and capture a different side of himself or herself, one that could possibly not have been expressed publicly.

Public images or private interests?

Yet we also wondered how private these images really were. Perhaps they were circulated among a small group of people with similar interests or desires. After all, how did they end up in Krafft-Ebing’s possession? Did the sexologist purchase them or did a medical colleague or patient pass them on?

What might Krafft-Ebing have made of these pictures? Based on what he wrote about cross-dressing in his book ‘Psychopathia Sexualis’ (1886), he might have thought that the individual had a “dress fetish” and was sexually aroused by wearing female clothing. He might also have looked at the pictures and wondered whether the individual was expressing homosexual desires or a wish to be a woman.

Discussing these questions in the exhibition, it became clear that it is impossible to offer definitive answers. After all, some visitors cautioned, the images might not have anything to do with the expression of innermost desires or a deep-rooted sense of self at all. Perhaps the subject was just having fun testing out or trying on different gender roles?

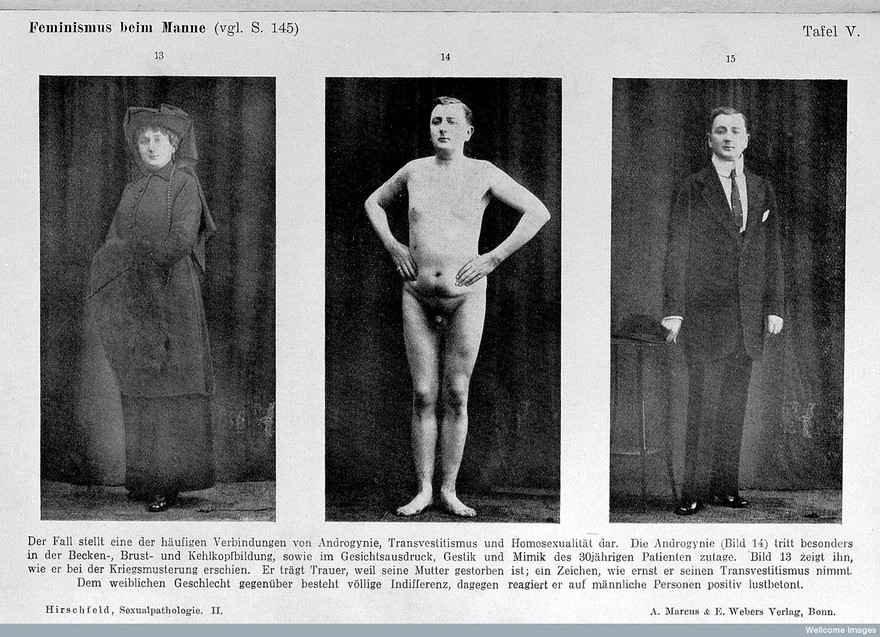

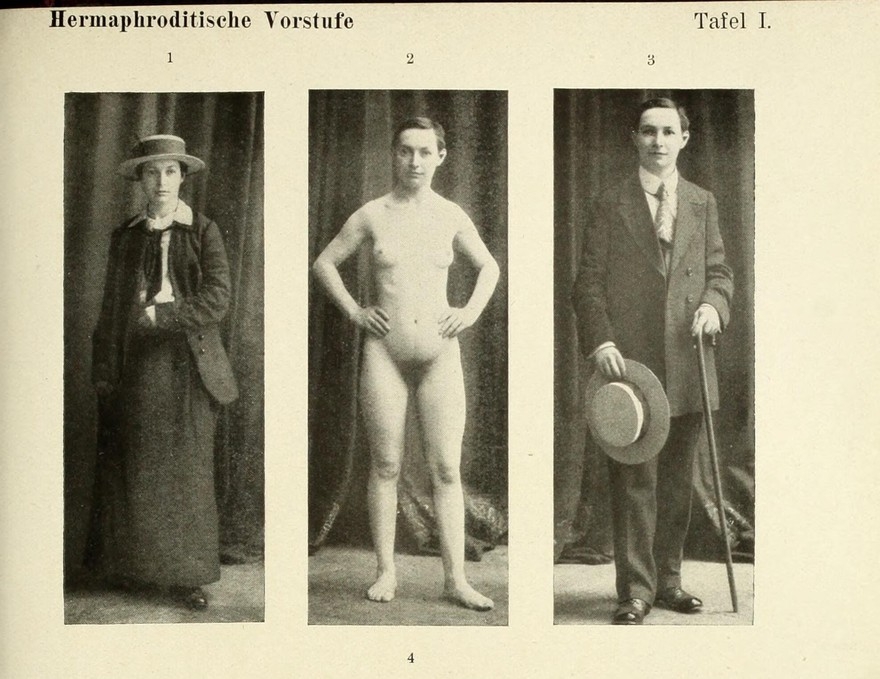

A male patient in Magnus Hirschfeld’s ‘Sexualpathologie’.

The other photographs we looked at raised similar questions, but they were taken from Hirschfeld’s medical textbook and so we had a lot more information on which we could draw in our discussion. The three images above show a male patient whom Hirschfeld diagnosed with ‘androgyny’, ‘homosexuality’ and ‘transvestism’ (a term coined by Hirschfeld himself in 1910 to describe cross-dressing).

Looking at the three images side by side, we talked about how it is not primarily the physical body that determines how we see ourselves and how we are perceived by others. A visitor put this succinctly when she said “it is the clothes that make the man or woman”, which allowed us to reflect on the many decisions we make every day to present ourselves as either male or female.

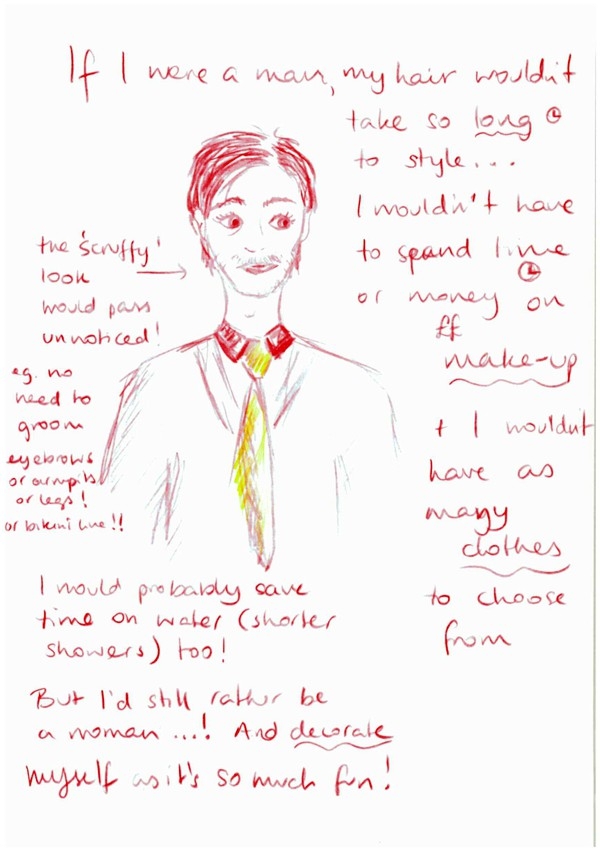

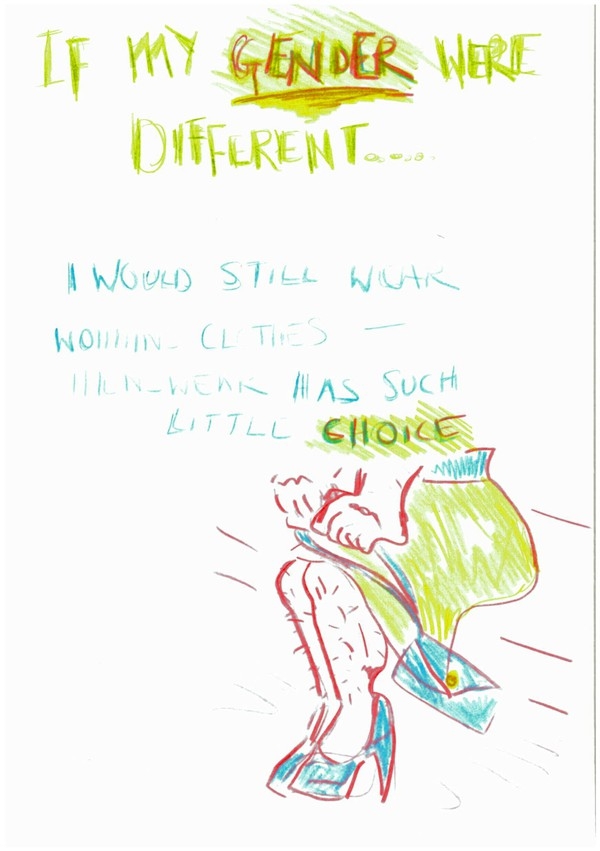

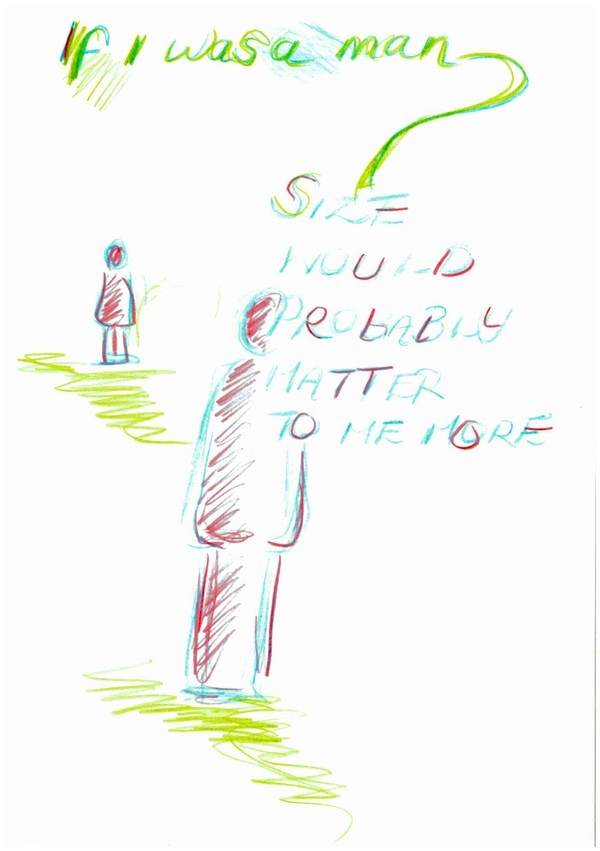

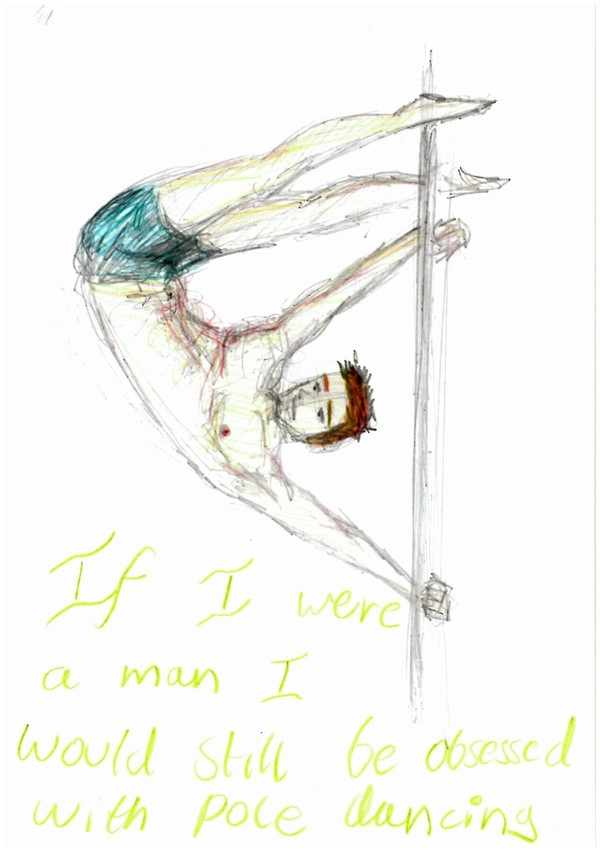

If my gender were different...

After the discussion, visitors explored these issues further in conversation with Visitor Experience Assistant Sol Szekir-Papasavva and by creating drawings and written statements in response to the question.

We also debated the case of Amanda/Amandus B, a patient who had first approached Hirschfeld in 1914 with the wish to obtain a legal name change and to wear male dress in public. If Amandus were alive today, he might understand himself as a trans man, but 100 years ago, Hirschfeld described the case as a form of “preliminary hermaphroditism”.

In accordance with Amandus’s wishes, Hirschfeld agreed that the patient should be allowed to live as a man. He justified his claim by arguing that Amandus was not really a woman in the first place, but psychologically and physically masculine.

Hirschfeld argued Amandus was not really a woman in the first place, but psychologically and physically masculine.

Visual manipulation

The photographs play a crucial role in supporting this claim and the images are carefully staged and posed so as to underline Amandus’s masculinity. Several visitors noted, for instance, how lighting is used to minimise the appearance of breasts in the nude shot. The three photographs are also carefully framed so as to give the impression that Amandus is taller in the third picture in which he wears male clothing.

Some visitors perceived this seeming manipulation of medical photographs as controversial: was Hirschfeld abusing his power as a medical doctor by ‘distorting’ the photographic evidence in this way? Others felt that we should applaud the sexologist for collaborating with his patient and allowing Amandus to claim and visually construct his own gender identity.

At the heart of this debate were fundamental questions that kept coming up throughout the event: can a photograph ever be expected to tell a simple truth? And can there ever be a simple truth when it comes to our gender identities and sexuality in the first place?

About the author

Dr Jana Funke

Jana Funke is an author, literary scholar and historian of sexuality. She is a Senior Lecturer in Medical Humanities at the University of Exeter and in 2015 was awarded a Wellcome Trust Joint Investigator Award to direct (together with Kate Fisher) a major five-year project on the cross-disciplinary history of sexual science.