Ancient Greek and Roman bodies are often seen as flawless – cast in buff bronze and white marble. In ‘Exposed, The Greek and Roman Body’, classicist Caroline Vout reveals them for what they truly were: anxious, ailing, imperfect, diverse, and responsible for a legacy as lasting as their statues. In this abridged extract, she explains why questions asked about the body in antiquity are still relevant today.

Naked, not nude

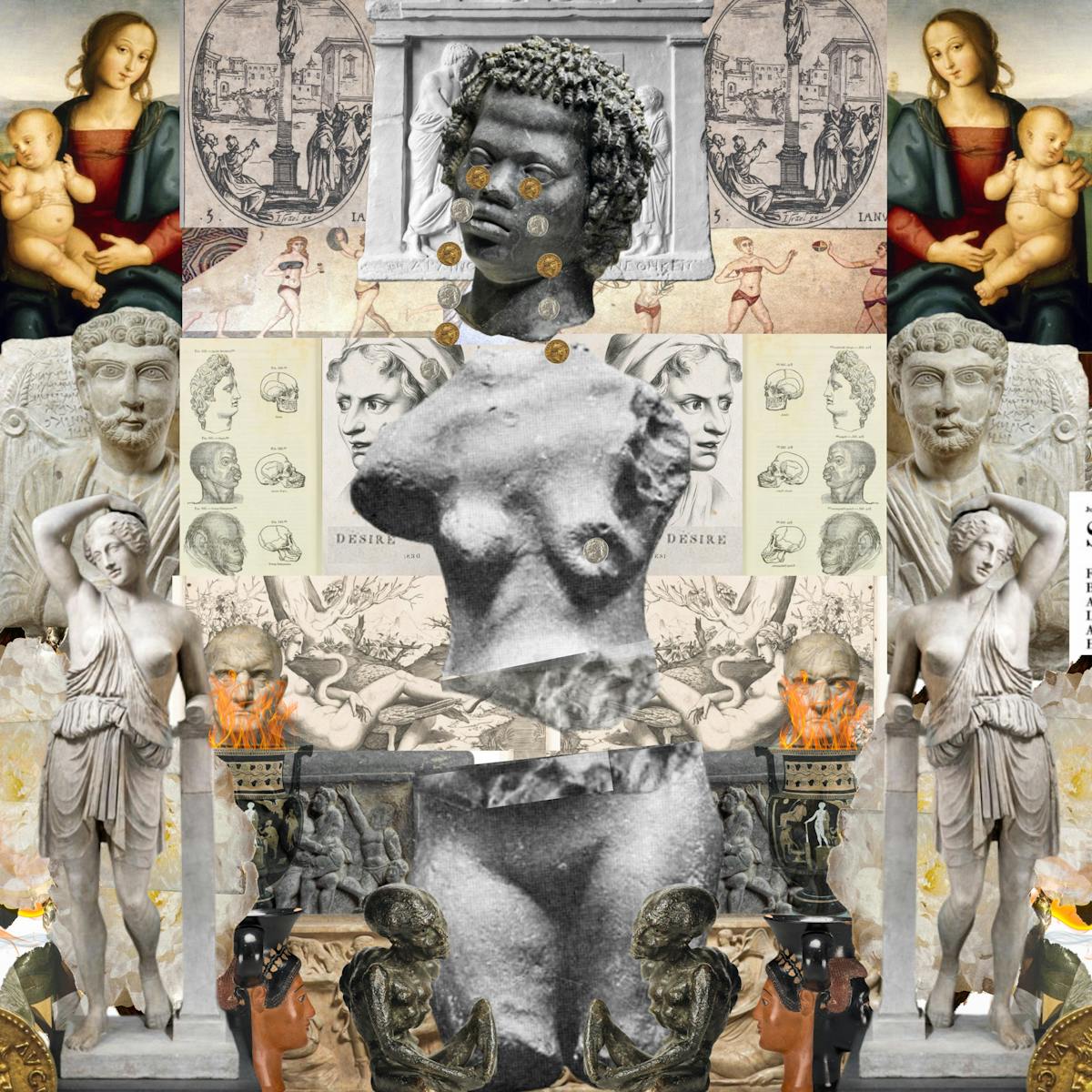

Words by Caroline Voutartwork by Funmi Lijaduaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Book extract

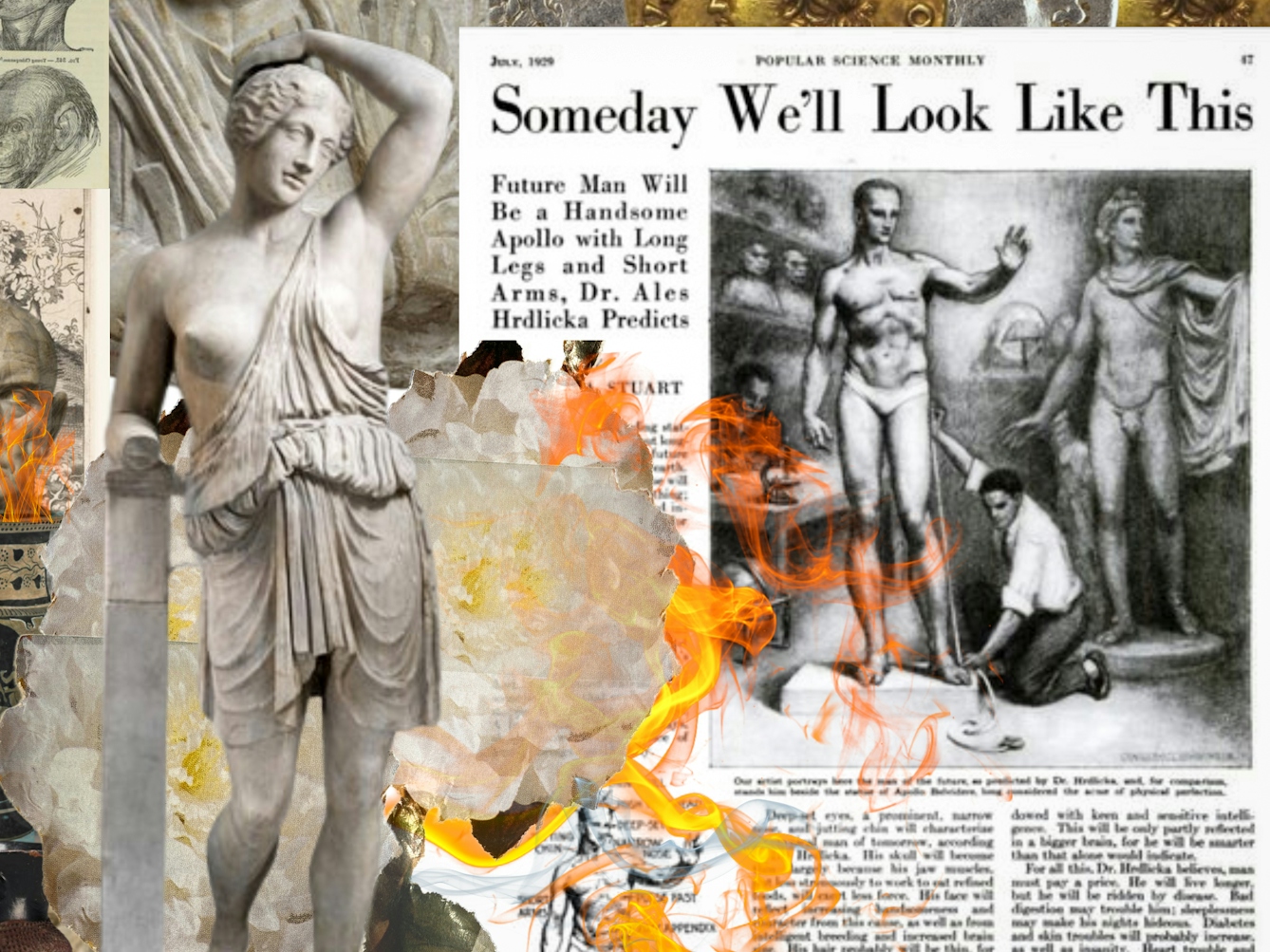

We don’t have to sympathise with the Greeks and Romans to appreciate that centuries of cultural investment have made them special. ‘Special’ is not the same as superior. We can ask the same questions about the body as they did without condoning their answers.

Where do humans come from? What makes them human, autonomous, able to act, and act responsibly? What happens to these bodies, and the forces that animate these bodies, when a person dies?

These are all questions that were debated over and over in antiquity, and questions that still drive today’s post-human and trans-human thinking, leading some people to spend tens of thousands of dollars having their bodies, or only their heads, frozen in liquid nitrogen, in the hope of future restoration.

Is the body so superfluous in determining our personhood? Many ancients would have thought that it was, yet many used their philosophical training to prolong life in the writing of medical treatises on organs, diseases, diet, and on the practice of complex surgical procedures.

Cosmetics, perfume and gym membership were big business, and not only because the future of the species depends on attracting a mate, but because, as the popularity of contraception attests, there was serious commitment to pleasure.

Gym membership was to Greek culture what bathing was to Roman culture: both of these activities were part of what made these peoples distinct, in their eyes, from barbarians.

In fifth-century BCE Greece, exercising nude turned men into citizen men, by training them to secure glory for their cities in local and panhellenic athletic competition, and (just as important for their formation as fully fledged adults) to attract the admiring glances of other citizen males.

“Gym membership was to Greek culture what bathing was to Roman culture: both of these activities were part of what made these peoples distinct, in their eyes, from barbarians.”

A human hierarchy

Romans were staid in comparison, all receding hairlines and cumbersome togas. Whatever Romans got up to in private, or dreamed of getting up to, love between citizen men was publicly frowned upon.

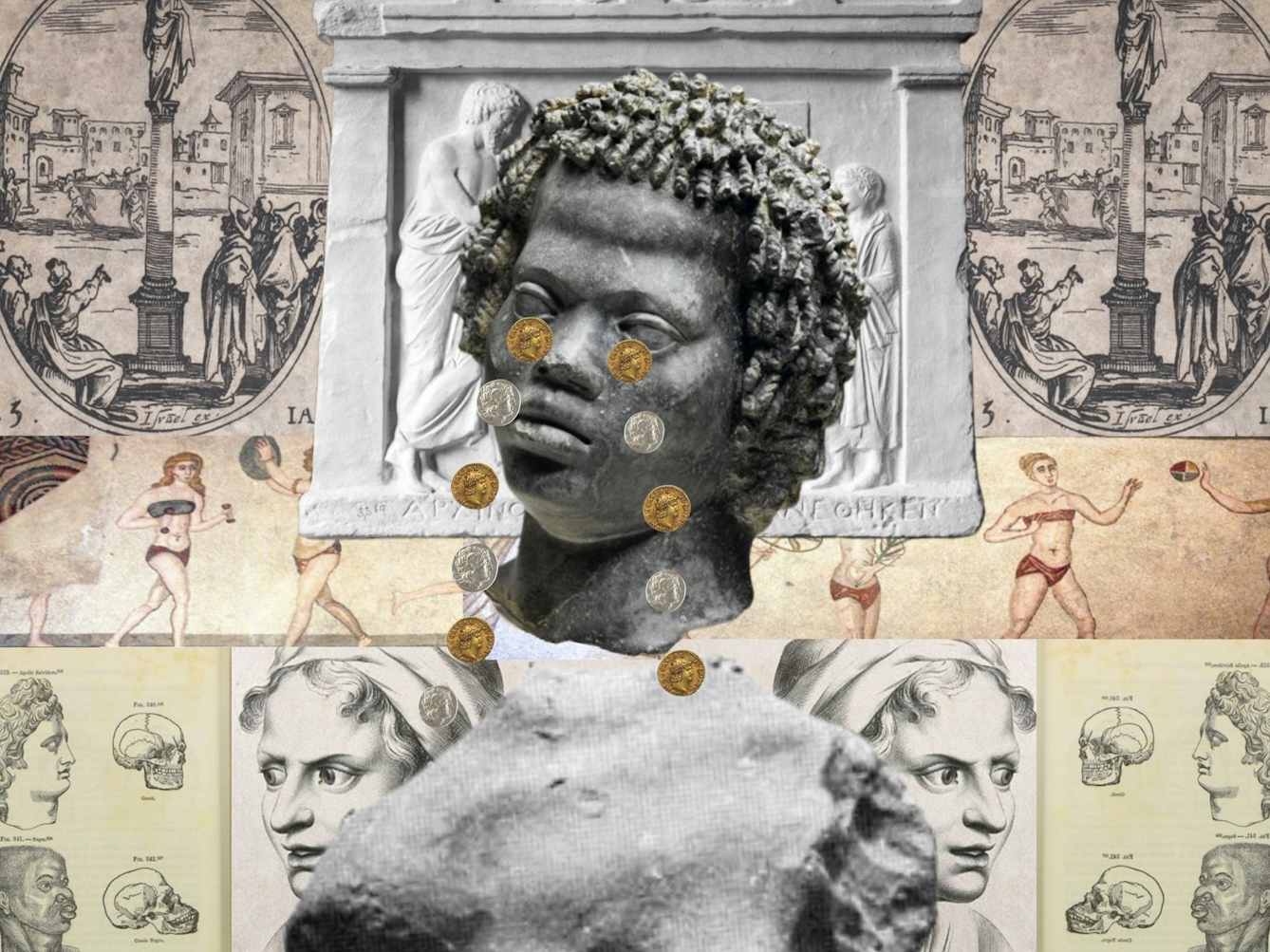

Not that the Romans were averse to getting their kit off. Towns and villas all over the Roman Empire had lavish bathhouses, with versions of statues such as Polyclitus’s Spearcarrier and figurative mosaic flooring designed to make bathers more self-conscious about their bodily vigour or inadequacy.

These feats of engineering and artifice, and the heightened awareness of the body that they bred, were, from Rome’s perspective, part of the civilising process. But hierarchies were hard to wash away.

When the emperor Hadrian, who had a penchant for public bathing, caught a war veteran rubbing himself up and down against the wall because he did not have anyone to remove his oil, he gave him slaves and cash towards their upkeep. When, on his next visit, there were numerous men doing the same, he ordered them to rub each other!

For many, life was tough. At the bottom of the social hierarchy, enslaved bodies were denied full personhood and the protection that that demanded. A funerary monument from Amphipolis in northern Greece marks this all too graphically: in its lowest tier, slaves are led like pack animals, chained at the neck. In the tier above, they work like Trojans. At the apex, they serve the deceased, Aulus Caprilius Timotheus, who reclines on a banqueting couch, larger than life.

The monument’s inscription informs us that Timotheus was a slave trader (‘body-seller’ in Greek): his enjoyment of life, and visibility in death, is built on his men’s back-breaking labour. Compared to the care he devotes to his body, their bodies are compromised, yoked like a team of oxen, or, in the scene at the top, where they tend to his every need, are further evidence, like the horse to the right, of his enviable resources.

The only other thing the inscription tells us is that Timotheus is a freedman (i.e. himself an ex-slave). His metamorphosis is worthy of Ovid.

“Timotheus was a slave trader: his enjoyment of life is built on his men’s back-breaking labour. Compared to the care he devotes to his body, their bodies are compromised.”

The issue of self-control

Women were defined by their bodies in a different way again, their purpose in life being to have babies. If they were not sexually active, they were deemed a danger to themselves and to society, as wild as their wombs that were thought to wander their bodies in search of moisture.

If they were sexually active, they were also a danger to society: a man had to know that the child she was carrying was his – hence the premium put on seclusion and marriage. However educated or moneyed a woman might be, her body made her a second-class citizen.

But it was not only “weak women” that struggled with self-control. The battle to balance physical urges with rational thought made everyone in the Greek and Roman world human. Sleep with too many men, or women, or grieve excessively for a dead wife or child, and even an elite man was open to charges of effeminacy.

The battle to balance physical urges with rational thought made everyone in the Greek and Roman world human.

The need to control the body extended beyond the boundaries of life itself: for many, death constituted liberation, escape from one’s bodily baggage, but it still had to be managed in the right way, and the corpse properly disposed of.

Control of one’s body was an esteem-indicator for anyone in public office; being in the public eye left them especially exposed. The gods were an exception. By society’s standards, their cruelty and promiscuity were off the scale – proof of their extraordinary status.

“Women were defined by their bodies in a different way again, their purpose in life being to have babies. If they were not sexually active, they were deemed a danger to themselves and to society.”

Exposing Greek and Roman bodies

Human bodies are inevitably born of nature and culture – always bodies in time and space, genetically coded bodies (not that the Greeks and Romans knew about genes, or amino acids, or proteins either), fleshed out by life experience, by theory and practice, ambition and fantasy as much as by reality.

And it is this ‘relativism’, the dependence of the human body on other bodies, human and divine, and on its specific physical and intellectual locale, which gives it meaning. Recognise this, and none of us are Greeks, not in the soppy sense meant by Shelley. Nor are we Romans. But acknowledging our distance from them is more productive than forging a false friendship.

Approach the bodies that populated Greek and Roman culture from this respectful, sceptical stance, and there is a chance to see past inherited ideals. It is time to take the dust covers off the Greeks and Romans; and to encounter their bodies not nude, but naked.

‘Exposed, The Greek and Roman Body’ is out now.

About the contributors

Caroline Vout

Caroline Vout is Professor of Classics at the University of Cambridge. She is also Director of Cambridge’s Museum of Classical Archaeology and has curated exhibitions at the Fitzwilliam Museum and at the Henry Moore Institute in Leeds. Carrie has appeared on ‘Woman’s Hour’ and ‘In Our Time’, and contributed pieces to magazines such as Apollo, Minerva, History Today, and to the Times Literary Supplement and Observer. In 2012 and 2013, she chaired the judging panel of the John D Criticos Prize, and from 2019 to 2024 holds the Byvanck Chair at Leiden University. She has given public lectures across the world, and is regularly invited to talk to schools.

Funmi Lijadu

Funmi Lijadu is a writer, artist and publicist with an interest in social issues, identity and surrealism. She has been commissioned by clients including the Tate and Tinder. Her articles are wide-ranging and tackle issues surrounding culture, gender and climate justice. Her work has been published in Cosmopolitan, gal-dem, Metro UK and many more. In a recent article for gal-dem, Funmi explored the connection between TikTok trends and eugenics.