Jazmine Miles-Long kneels down to open up the small freezer that sits on her studio floor. Each drawer is filled with clear ziplock bags, each bag is numbered, and each one has a body in it.

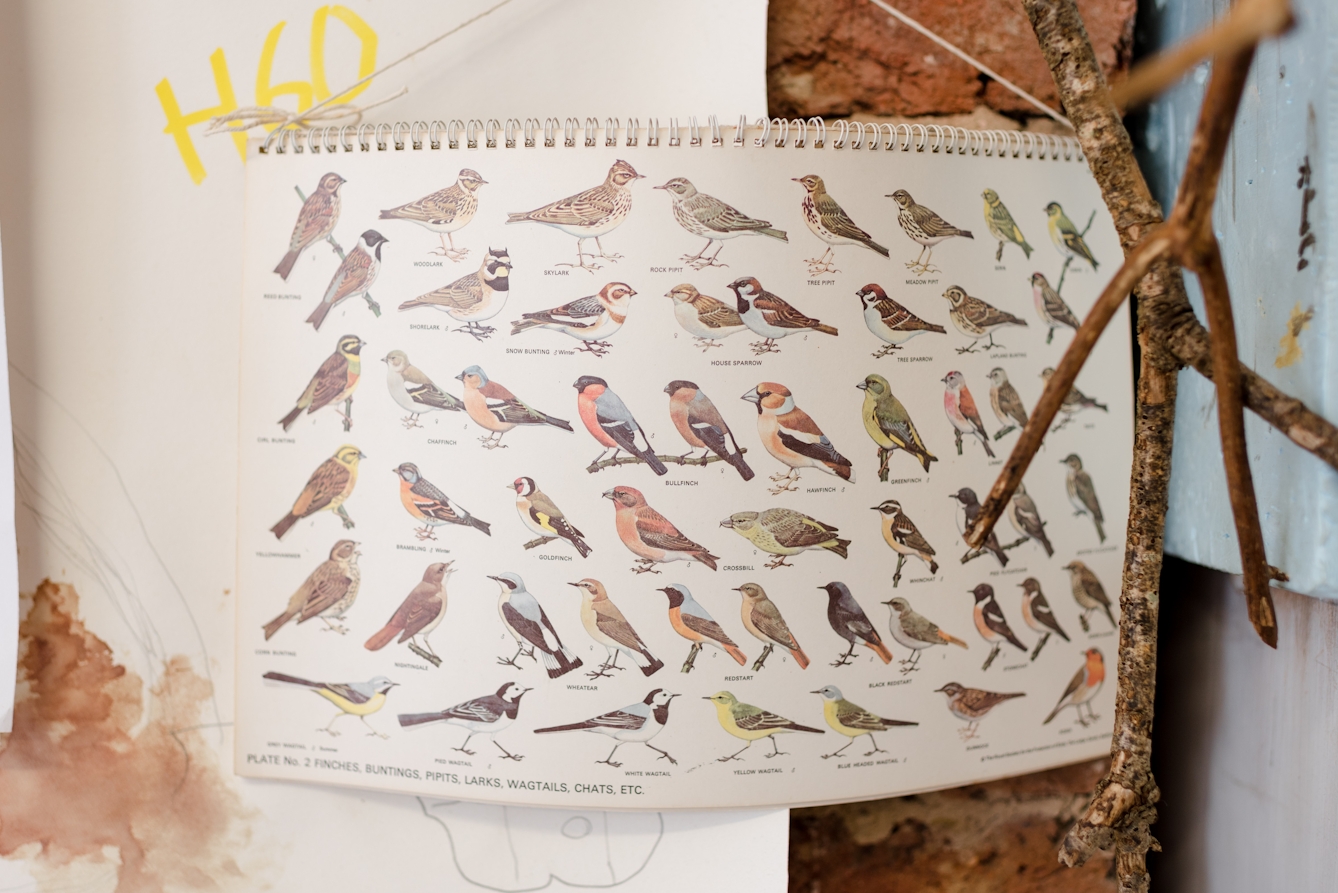

She selects a bag containing a juvenile greenfinch, takes out the skin, and begins washing it in a basin of warm, soapy water. A few basins of fresh water later, she places the bird on a clean towel. It’s now sodden, and rather sad with it.

Jazmine bends low over her workbench, her blue-gloved hands delicately working through wet feathers with a small brush and some long tweezers. She explains that, although the greenfinch looks like it has feathers sprouting all over its body, they actually grow from specific feather tracts. Large areas of the skin are in fact feather-free. It’s this kind of detail that doing taxidermy brings to light.

Jazmine handles the greenfinch skin with the methodical patience of a craftsperson, the cool eye of a surgeon, the enquiring mind of a zoologist, and the reverence of an animal lover. As she works, I ask why contemporary taxidermists take such exception to the word ‘stuffed’? “Because it suggests there’s no process,” she replies.

Process is everything. It’s invasive – if you end up dead on Jazmine’s desk she will quite literally turn you inside out. And it’s intimate – she’ll spend hours poring over your every intricate detail, determined to make you look your best. “People don’t realise how delicate and slow you have to be,” she explains.

Under the skin

Every skin Jazmine works on teaches her more about how strong or light her hands can be. She describes her touch as “knowing”. The finch’s skin is strong when wet, but still delicate, “almost like wet cigarette paper, it’s so thin”. When it dries it will become very fragile. Jazmine admits she’s become desensitised to the blood and guts that are an inevitable part of her work, but that doesn’t mean she isn’t fascinated by what goes on under the skin. “Wild animals are really lean, with fat in all the right places,” she says, clearly impressed by their efficiency.

The cleaning complete, Jazmine pulls out a hairdryer and begins blow-drying the bird. It’s an odd moment: the jets of hot air temporarily animate the skin, bringing it to a strange kind of life. The feathers fluff up and ripple. As well as volume, they start to regain their olive-brown greens, their banana-bright yellows, their soft, soft greys.

She lays the dry finch, tummy down, wings spread, on a towel so I can take a closer look. It’s the closest I’ve ever been, or probably ever will be, to a greenfinch. The bird’s beak, legs and claws are a delicate shell pink, and its characteristic boxy profile somehow seems more distinct now it’s dry, despite being without flesh. It’s tiny, and very beautiful.

In pictures

Ethical taxidermist Jazmine Miles-Long works on a juvenile greenfinch.

Thoroughly cleaning the feathers and skin is an essential part of the process.

Jazmine places wet tissue inside the finch to keep the skin supple.

Then combs through the wet feathers with tweezers.

The skin is strong when wet, but delicate, like "wet cigarette paper".

Once the greenfinch has been cleaned, it has to be dried.

Taxidermy is as intimate as it is invasive. Jazmine has a "knowing" touch.

Clean and dry, the finch's feathers regain their browns, yellows and greys.

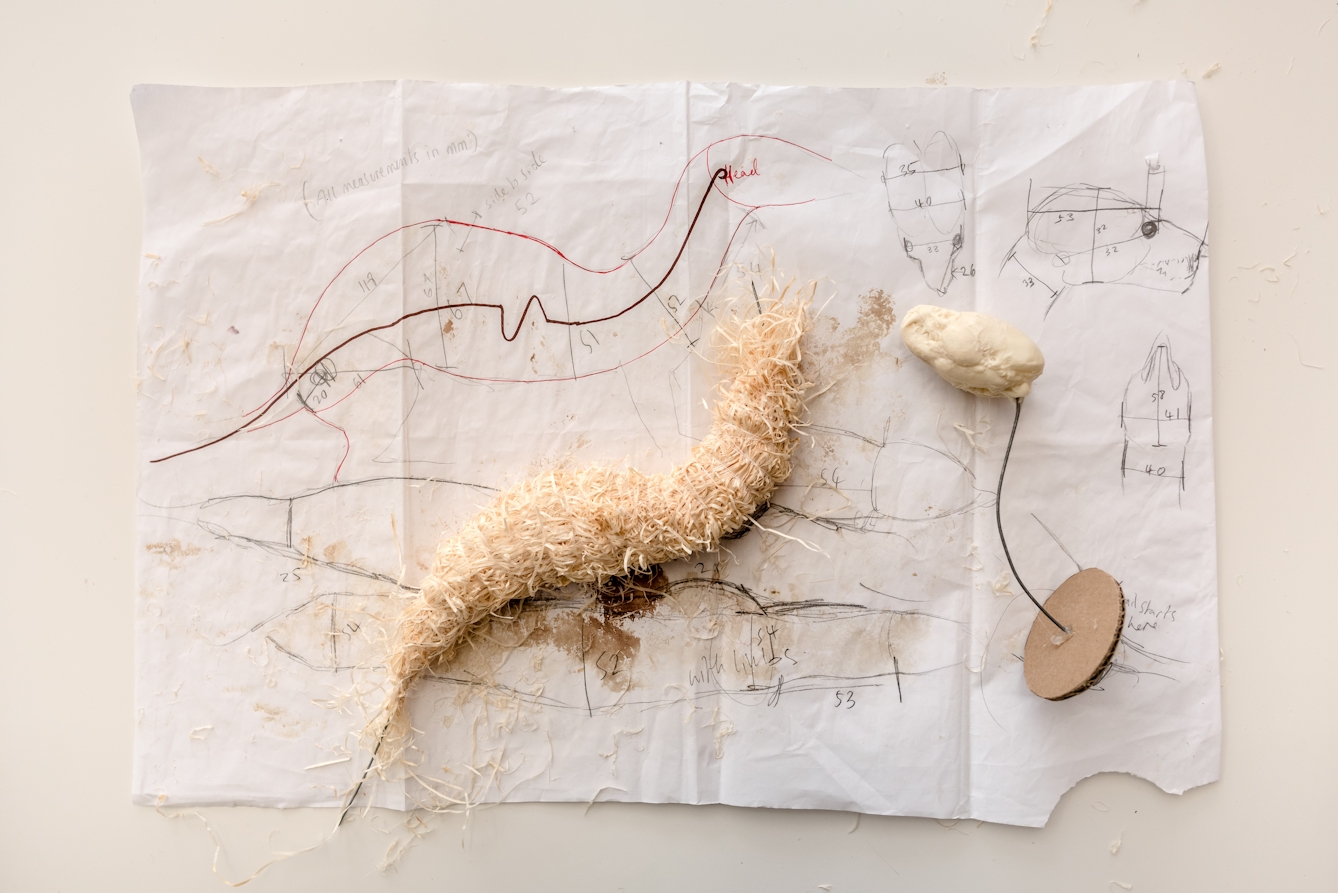

Her demonstration done, Jazmine places the finch in a fresh ziplock bag, numbers it, then files it away in the freezer. She’s carved a balsa-wood body for the bird, and explains how if she was working on a mammal the process of preparing the skin would be different. Rather than washing and cleaning, she would pickle and tan. The insides would be moulded from ‘wood wool’ (finely shredded wood), rather than carved from balsa.

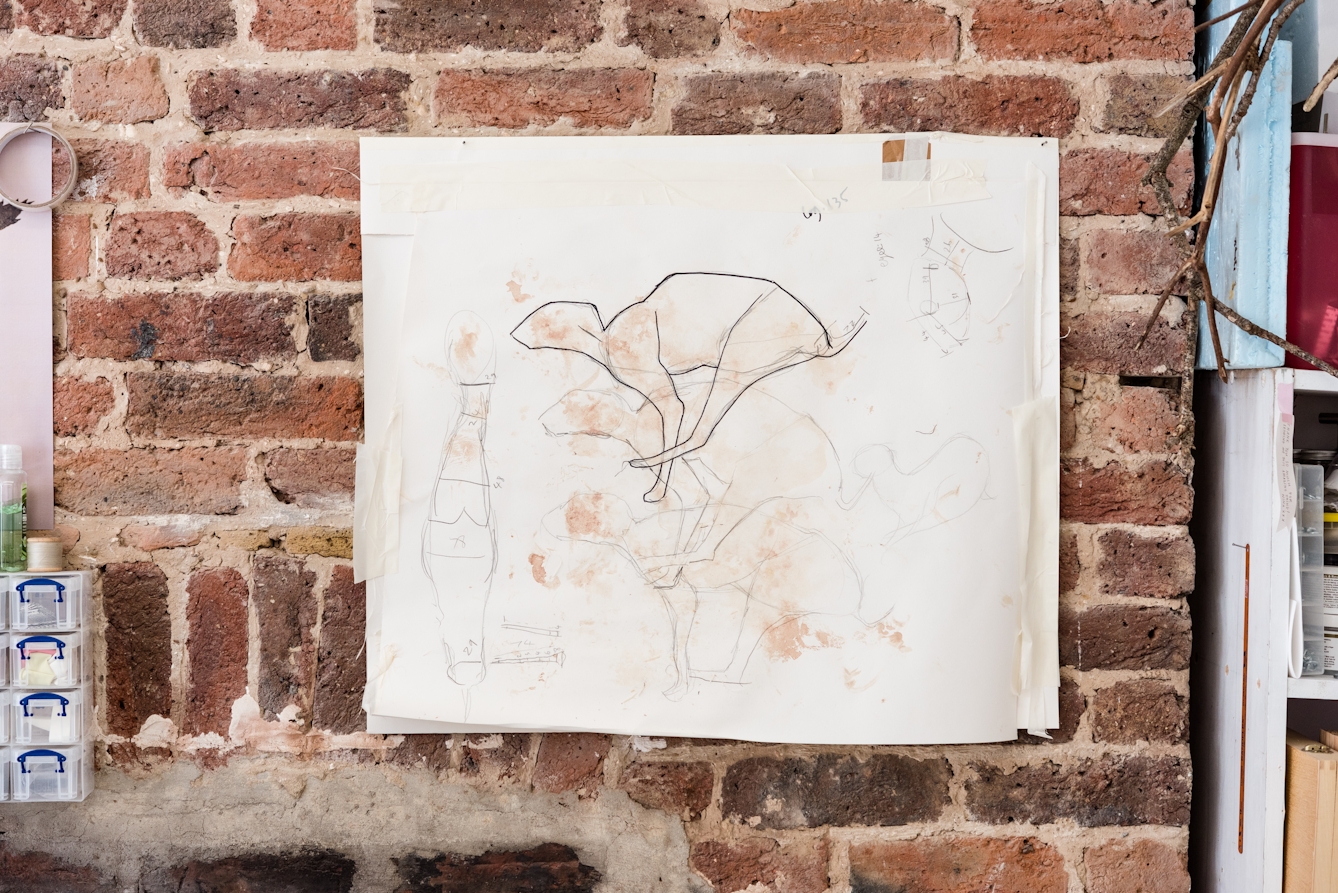

But one of the very first steps, whether working on bird or beast, is always to make a detailed plan. Jazmine does this by drawing around and measuring the animal, positioning it on a sheet of paper the way she wants it to look when it’s mounted. The plans she has pinned to her studio walls are stained with blood. She says that making a piece of taxidermy is, for her, about copying the individual in front of her. Every creature is different, and each teaches her new things.

Jazmine studied sculpture, and volunteered at the Booth Museum of Natural History in Brighton after university. She fell into taxidermy there, loving it for its variety and its craft. “It requires so many different skills, and types of making,” she explains. “You have to love animals. It’s a privilege to know more about them. I’ve learned so much from my making, seeing first-hand how a woodpecker’s tongue curls around the back of its head, between the skull and the skin, and how a rabbit’s whiskers grow right into its brain.”

It’s an unusual job, and people are generally fascinated when Jazmine tells them what she does for a living. The questions she’s most often asked are: What’s the biggest thing you’ve ever worked on? (A cheetah, which died in captivity of cancer, in case you’re wondering. It was the most challenging thing she’s ever worked on, too); Are the eyes real? (No, never); Does the animal have to die in the pose it’s mounted in? (No, of course not). I ask about the smelliest thing she’s worked on, and she says a gannet. Seabirds stink because their stomachs are full of rotting fish.

In pictures

When making a mammal, Jazmine uses ‘wood wool’ to create the body.

She moulds the shredded wood around wire to make the body shape.

Detailed plans are essential if the finished animal is to look right.

For Jazmine, making a piece of taxidermy is about copying the individual animal.

She positions the animal on paper the way she wants it to look when it’s mounted.

The paper plans become printed with blood.

Jazmine describes herself as an ‘ethical taxidermist’, which is also a conversation-starter, because what does that mean? “Ethical is an annoying word,” she says, “but it’s the only way I can communicate about what I’m doing, because it makes people ask questions.”

She only works with creatures that have died of natural causes or by accident; never anything that has been purposely killed. How the finished work is presented and where it ends up are important, too. “I say no to a lot of things,” she says, “I’ll only do things that feel respectful. I don’t do trophy heads of any kind.”

Jazmine does do commissions, and her work for the artist Abbas Akhavan featured in ‘Making Nature: How we see animals’ at Wellcome Collection. The final fox, badger and owl that were on display represented Akhavan’s vision, rather than Jazmine’s, and he was keen to provoke. There were no cases, and no interpretation telling you what you were looking at, or what you should think. The animals were intended to look what they are: dead. The fact they were placed on the gallery floor was controversial for some, and proved that taxidermy has the potential to produce an emotional response.

Does Jazmine like the word ‘taxidermy’, which is derived from two Greek words: taxis, meaning ‘order’, and derma, meaning skin? Together they mean ‘the arrangement of skin’. “I love that word,” she says, while also admitting it’s complicated. “It’s broad, and can include so many things. Through my work I try to make the word have a better meaning.”

Although she accepts that dead animals make some people feel weird, and some will always insist on calling what she does ‘macabre’, Jazmine argues that, in most instances, it must surely be better to interact with a mounted animal that has died naturally or by accident than to see a wild animal alive but shut in a cage. Getting up close to an animal helps create a bond, and can open us up to new ideas and experiences.

Jazmine recently mounted a swift for the Booth Museum. In life the swift will likely have arrived in the UK in spring, staying until late July or early August. It will then have migrated through France and Spain to spend its winter in Africa, following the rains, and the insects they bring. In its afterlife the swift and its story are being used to teach children about refugees and dual identity, as well as bird migration. In his essay ‘Why Look at Animals’, John Berger talks about the “universal use of animal-signs for charting the experience of the world”. Jazmine’s swift seems an excellent example of that.

In pictures

Ethical taxidermist Jazmine Miles-Long's studio in Hastings.

“You have to love animals. It’s a privilege to know more about them."

Jazmine only mounts creatures that have died of natural causes or by accident.

Preserved skeletons in Jazmine's studio.

A work in progress.

Pencil drawings and plans pinned to the walls of Jazmine's studio.

Taxidermy derives from Greek: taxis, meaning ‘order’ and derma, meaning skin.

"Taxidermy is a partnership with a maker. It’s an animal and an object.”

Taxidermy transforms once-living things into something very different. The “biological death of the living beast is the birth of the specimen,” as Samuel Alberti says in ‘The Afterlives of Animals’. There is of course a difference between how we relate to an animal in its new form, and how we would have done when it was alive. Does arranging nature in this way bring us closer to it in more than just a physical sense? And could ignoring the person in every piece of taxidermy actually be driving us further apart?

Jazmine points out that when we look at a piece of taxidermy we often just see the animal, rather than acknowledging what it is now, and the relationship between it and its maker. We might wonder what the animal’s life was like and how it died, but we often ignore the fact so much work and care has gone into creating what it has become after death.

“The craft has developed over such a long time, but it doesn’t have the prestige that others have because we are working with dead animals, and also because of where the work ends up, often presented anonymously with no detail about the maker,” says Jazmine. “A piece of taxidermy is a craft object that’s been made by a person; it’s not just an animal. It’s a partnership with a maker. It’s an animal and an object.”

Find out more about Jazmine’s work at jazminemileslong.com.

About the contributors

Helen Babbs

Helen is a Digital Editor for Wellcome Collection.

Thomas S G Farnetti

Thomas is a London-based photographer working for Wellcome. He thrives when collaborating on projects and visual stories. He hails from Italy via the North East of England.