Many common remedies, as well as the more exotic experimental drugs, were taken throughout the 19th century, with more people than ever using them. What was the social and cultural context of this development?

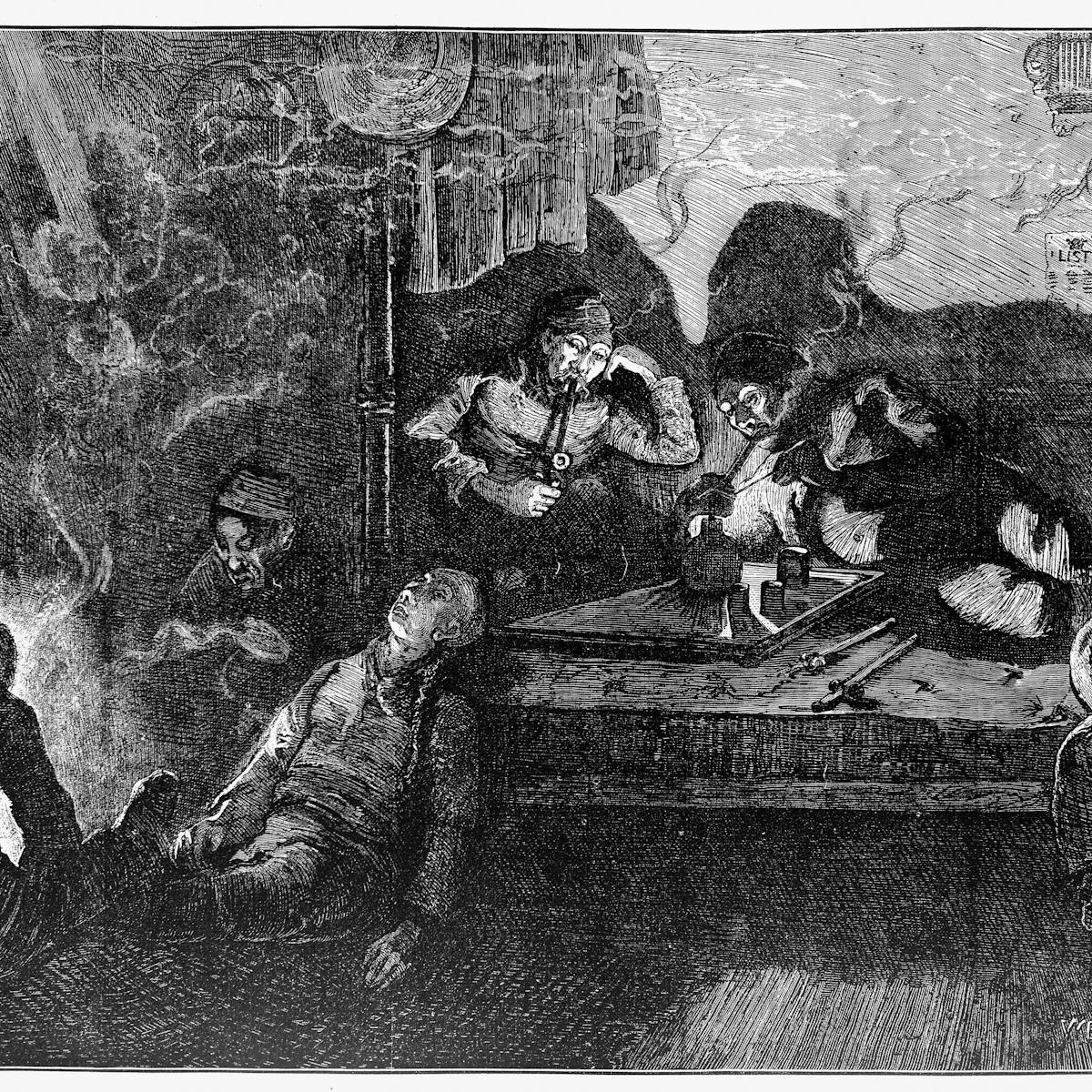

There is something rich and romantic about the Victorians and their drugs. The works of Thomas De Quincey, Arthur Conan Doyle and Charles Dickens all owe more than a little to potent drugs that were freely available in their time. Thomas De Quincey, in his work ‘Confessions of an English Opium Eater’, states that a philosopher who takes opium will experience a phantasmagoria of dreams.

But the 19th-century pharmacopoeia was actually much more mundane: most of the populace were taking these newly illegal drugs for the common complaints of cold, cough and toothache.

Researchers have long explored aspects of the many common remedies taken throughout the 19th century, as well as the more exotic experimental drugs. There was the drug as inspiration, the drug as medicine and the drug as a menace.

How drugs came into society

Mike Jay, the author and cultural historian who co-curated Wellcome Collection’s ‘High Society‘ exhibition, has expressed relief that we are now beginning to have a ‘grown-up’ conversation about current illegal drugs, and has looked at how some of these drugs came into society.

More: The origins and meanings of pharmacy symbols

The 19th century was a crucial period of drug-taking development both in terms of potency and plurality. The Victorians took not just alcohol and opium but cannabis, coca, mescal and, with the invention of the hypodermic needle in the 1840s, morphine and heroin. The 19th century also saw the origins of drug control, and the medicalisation of addiction to these substances.

The Victorians took not just alcohol and opium but cannabis, coca, mescal and, with the invention of the hypodermic needle in the 1840s, morphine and heroin.

Legal vs illegal drugs

Victorians are often mocked for their prudery and restraint, but they seem to have been venturesome and even wild in their pursuit of altered mind states. What can explain this?

Dinah Birch looks at what these drugs meant in the context of Victorian society. Birch supposes that Victorian austerity was part of an inclination to sensation-seeking. The high from success and the high of narcotics are partners in pleasure. She quotes 18th-century philosopher Edmund Burke, who said, “Under the pressure of the cares and sorrows of our mortal condition men have at all times called in some physical aid to their moral consolations.”

The Victorians were not unique in their interests, but drug taking was important to their culture, and the promotion of drugs by industry, particularly the still-legal tobacco, tea, coffee and alcohol industries, cemented this in Victorian Britain.

A serious scientific culture developed towards the middle of the 19th century, says Birch, that led to self-experimentation with drugs. Dr Michael Neve agrees: his readings of three separate accounts of drug experimentation by S. Weir Mitchell, Henry Havelock Ellis and Mark William James reveals an eagerness to understand more about the mind, the body, and the connection between altered mental states and something more spiritual. Experimentation and exploration led to enlightened thinking.

The Victorian pharmacy

Most Victorians were poor and life was hard: drugs and medicines were vital. Chemists were available for free whereas doctors were not, and most Victorians got their drugs over the counter, without a prescription. The wide range of drugs available at the time is intriguing.

As medical historian Stuart Anderson says, the Victorian chemist stocked not only patent and proprietary medicines, ready made, but nostrums made by himself and raw ingredients for home remedies. There was laudanum for dysentery, chlorodyne for coughs and colds, and camphorated tincture of opium for asthma.

Opium pills were coated in varnish for the working class, silver for the rich, and gold for the very rich. Angelic children frolicked on the bottles of Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral, a mixture of alcohol and opium that would now be deemed a poison. Coca leaf, from which cocaine is now obtained, was advertised as a nerve and muscle tonic, to “appease hunger and thirst” and to relieve sickness.

Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral was a mixture of alcohol and opium.

The influences of drugs on Victorian literature

Princess Puffer in Charles Dickens’s ‘Edwin Drood’ and Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes both shoot up cocaine, points out English lecturer Julian North. And although Charlotte Brontë never experimented with drugs, there are apparent influences of her brother’s opium addiction in her writing.

Division is a key aspect of Victorian society, says North. On the outside, the Victorian is socially respectable, underneath they are bubbling away. This reverberates in their literature. It is most notable in the transformation of Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr Jekyll into Mr Hyde. (Allegedly, Stevenson wrote the novel during a six-day cocaine binge.)

Brontë’s character Lucy Snow in ‘Villette’ is outwardly mousey, inwardly passionate and imaginative. John Jasper from ‘Edwin Drood’ is a choirmaster who visits opium dens. Oscar Wilde’s smooth-faced Dorian Gray is angelic and beautiful, but locked away is his horrifying portrait. Thrill-seeking Sherlock Holmes says, “I abhor the dull routine of existence, I crave metal stimulation.”

It is no accident that drugs in Victorian culture are entwined with the emergence of detective literature. Opium and cocaine, like detection, hold the power to trace back and uncover our darkest motives. Sometimes these drugs are portrayed as crimes, accomplices to murder. But they are also portrayed as a liberation, a fight against the boredom of respectability. Victorian writing anticipates our thoughts about what drugs can do to us.

Michael Neve’s exploration of personal drug narratives on mescal, peyote and nitrous oxide produce some wonderful quotes. “It is the most democratic of the plants which lead men to an artificial paradise,” wrote Henry Havelock Ellis of mescal. A phrase like this is a far cry from the mundane use of laudanum for toothache. He wrote that under the influence of mescal, the world becomes sublime. And from the sublime to the ridiculous, Neve suggests that Havelock Ellis’s description of eating a biscuit during his experimentation led to the naming of satirical band Half Man Half Biscuit nearly 100 years later.

The medicalisation of addiction

Addiction has been recognised as a medical problem since the middle of the 19th century. But is it a sin, a crime, a vice or a disease?

The medicalisation of addiction, says historian Louise Foxcroft, came with the growth of the scientific profession and the medial marketplace. There was a growth of specialism and new terminology. First there was the inebriate, then the addict, and later the morphinomaniac, who took his place between the neurotic and the melancholic.

Christian evangelists regarded addiction as a sin linked to the story of Adam and Eve. George Beard, an American doctor, argued that addiction was an eminently treatable, heritable disease related to the quality of brain nerve tissue. Addicts were often treated brutally, with scalding baths, mustard plasters and physical force, all applied with contempt. The addict himself was seen as the source of the problem and treated without looking at his environment.

Foxcroft notes that not a lot has changed on this topic. There is still the question of what an addict is and how we treat them. Victorian morphine addicts were weaned off their ‘demon’ with heroin. Now the substitute is methadone. Do we need to get away from the Victorian method of looking at the individual and, rather, look at society?

Synthetic drugs

Whether it’s mephedrone, miaow-miaow or ecstasy, we are now moving away from the Victorian medicine cabinet to manufactured drugs, synthesised specifically for the needs and desires of our current lives. There is a very radical drive within human nature to find ways of transcending the mundane.

Our current situation with illegal drugs here might seem the result of a very modern society, but our relationship with narcotic substances goes back a long way, to Queen Victoria and beyond.

About the author

Louise Crane

Louise Crane is a Picture Researcher for Wellcome Collection. Her interest in Victorian medicine started at university and peaked with her dissertation on opiates’ metamorphosis from remedy to public enemy.