In ‘Rumbles, A Curious History of the Gut’, cultural historian Elsa Richardson leads us on a lively tour of the gastroenterological system. In this extract, Elsa explores the stomach’s influence over our thoughts and feelings, why trusting your gut could well be good advice, and how a small dog helped shape what we know about the gut–brain connection.

Your gut’s instincts

Words by Elsa Richardsonphotography by Steven Pocockaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Book extract

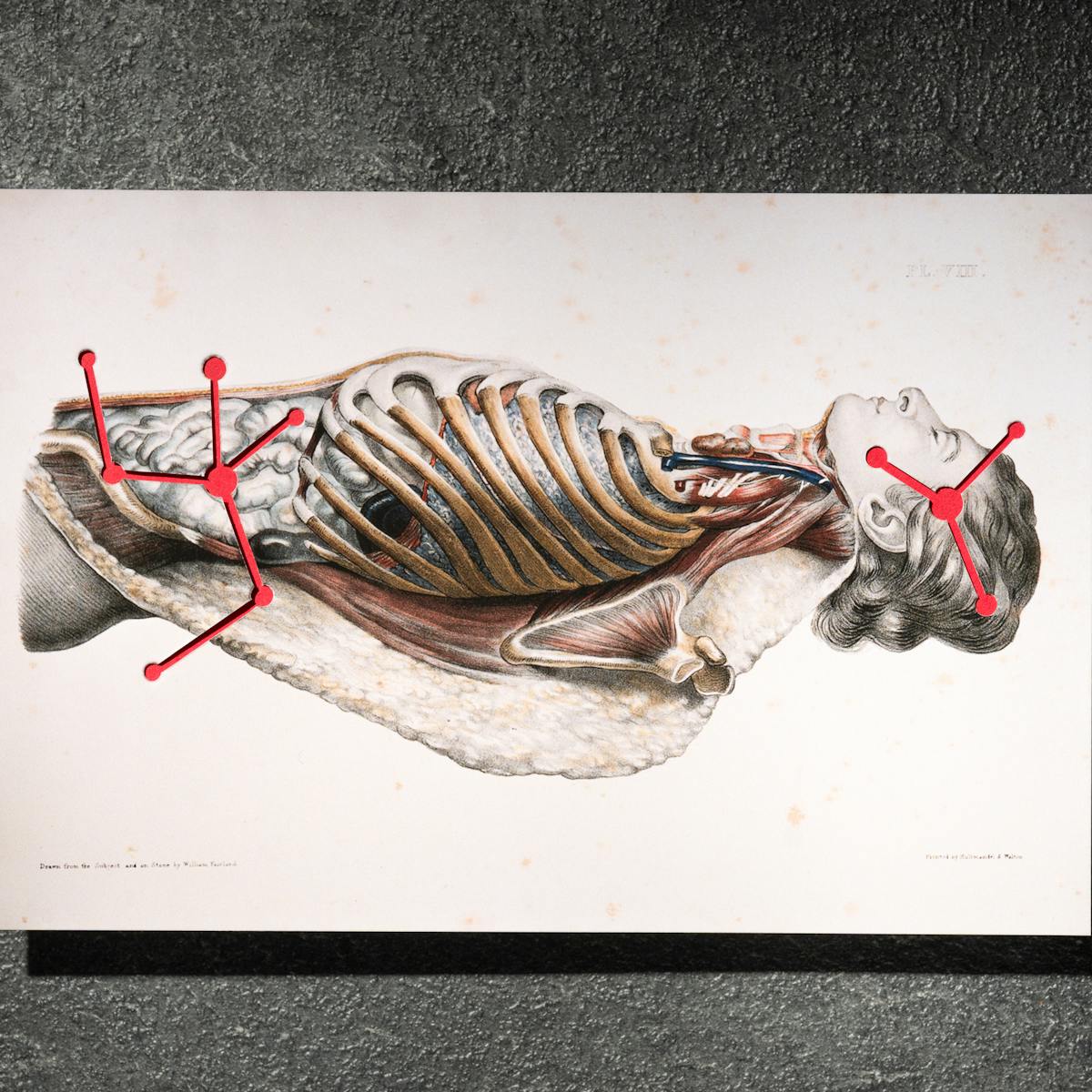

We have not one, but two brains. This remarkable quirk of human anatomy was discovered in 19th-century Breslau by Leopold Auerbach, a German neuropathologist who developed a method of staining cells that made it possible to observe the microscopic structures of the nervous system for the first time.

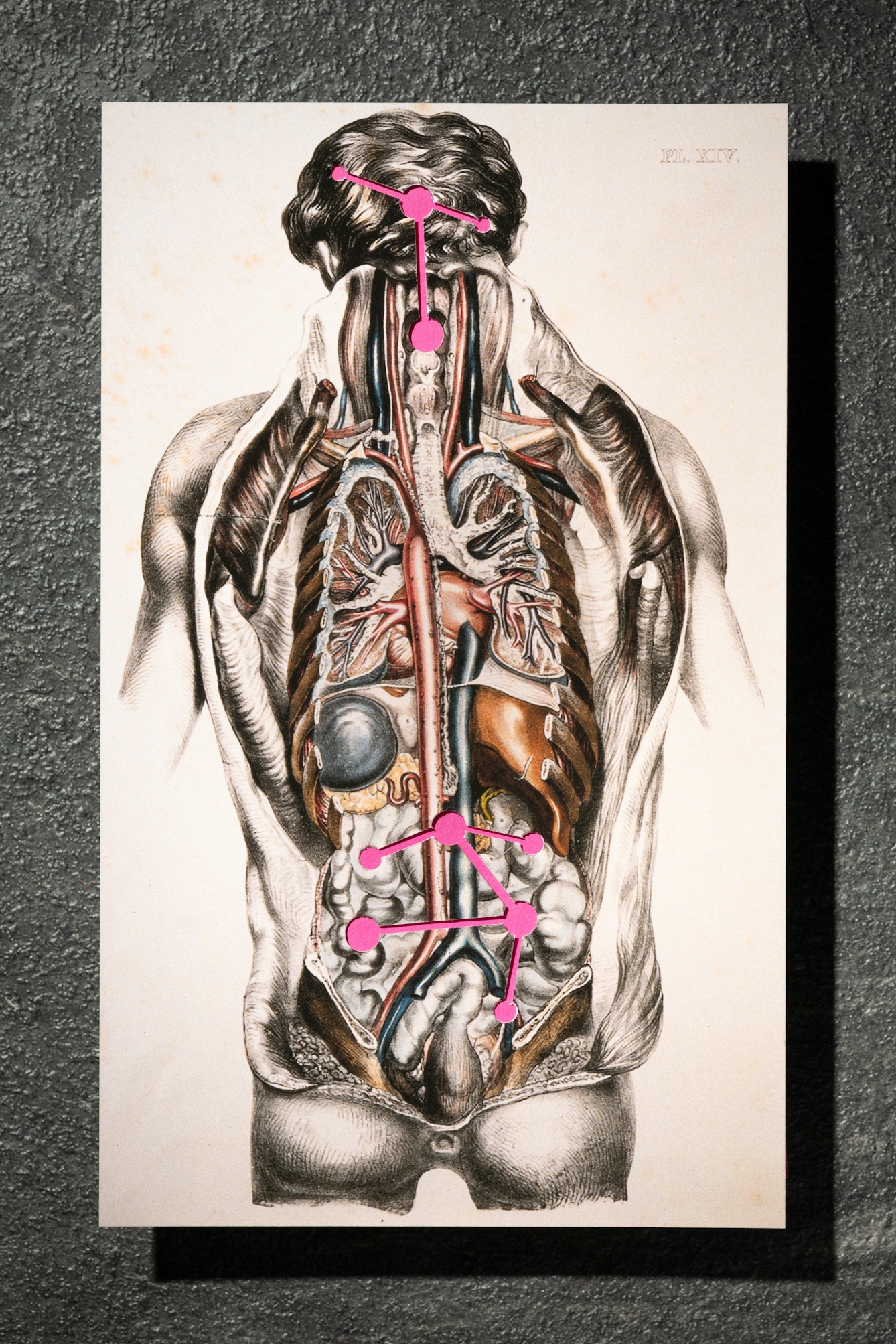

Auerbach’s major discovery was the myenteric plexus, or Auerbach’s plexus, a group of cells that direct the movements of the gastrointestinal tract, which include neurons like those found in the brain. These neurons form part of an army of 100 million lodged in the alimentary canal, capable of operating independently of the central nervous system and responsible for much more than just the daily grind of digestion.

Today scientists point to the existence of cells that allow the gut to speak directly to the brain, and those working in the emerging field of neurogastroenterology have suggested that the stomach might have a role to play in cognition.

This cutting-edge research speaks to the familiar advice to “follow your gut” or “trust your gut instinct”, which rests on the assumption that the stomach might know something the brain does not. Or that, freed from the rationalising tendencies of the mind, emotions might be felt more acutely, more authentically, in the gut.

The idea of the thinking belly has long shaped debates about the nature of intelligence itself.

This association is more than metaphoric – medical thinkers throughout history have identified the stomach as a peculiarly learned organ. Modern science is uncovering new facets of the gut–brain connection all the time, but the idea of the thinking belly has long shaped debates about the nature of intelligence itself.

“We have not one, but two brains.”

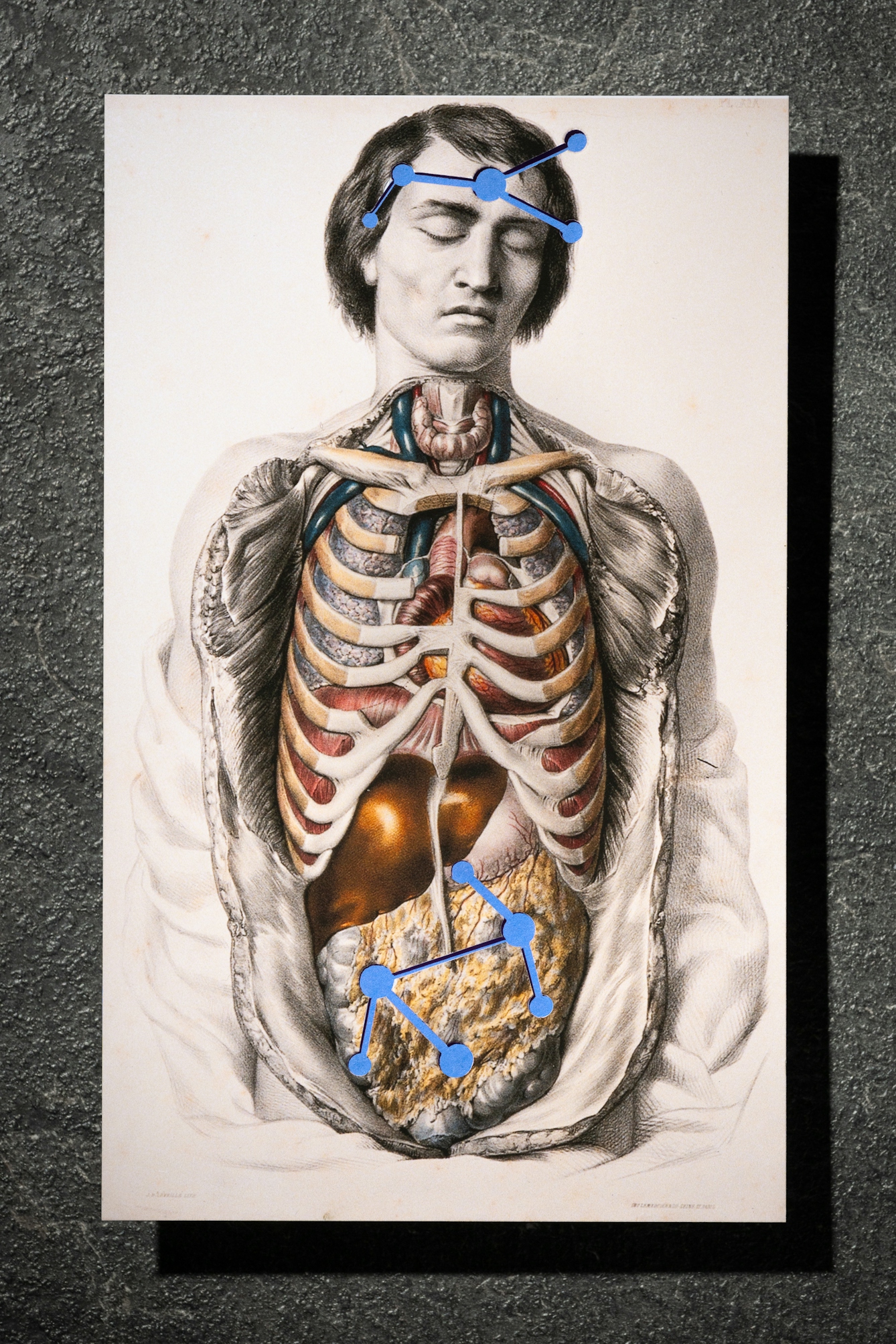

Much of our current fascination with the gut has been fuelled by a growing appreciation of the myriad ways that its workings are entangled with those of our higher cognitive functions. Neurologists have been tracing the path of the vagus nerve, which runs from brain to bowel. Elsewhere, biologists mapping the microbiome have discovered that bacteria living in the intestines help to regulate the production of the biochemicals responsible for stimulating neuronal growth.

Science has positioned itself at the forefront of this revolution in how we understand intelligence, but many of the questions it has raised – where is intelligence located in the body? What are its limits? What differentiates human from animal? – have been taken up with equal enthusiasm by philosophy, literature and popular culture. Moreover, while science is often presented as objective and value-free, it is undertaken within and shaped by a particular social context.

The work of these complex forces can be hard to discern in the present, but by taking a historical view, it is possible to conceive of the gut–brain connection as scientific knowledge that has been produced in relation to different kinds of discourse and different understandings of the body.

The intelligent gut

The modern history of the gut–brain connection begins with a small brown terrier dog. Around the turn of the 20th century, the Department of Physiology at University College London played host to a series of experiments that would not only lead to the discovery of hormones but would also reveal the true scope of the enteric nervous system.

Though it was Auerbach who, peering at a section of bowel through his microscope in 1863, first spied the thick bundle of nerves nestled in between layers of muscle, it was only with the work of two British scientists – William Bayliss and Ernest H Starling – that the significance of the myenteric plexus finally began to be understood.

Close friends, collaborators and eventually even brothers-in-law, the pair conducted their investigations using anaesthetised dogs. One of those unfortunate canines, a rather scruffy creature with alert eyes and soft ears, would become the subject of immense public controversy, a high-profile trial, riots and even a specially commissioned statue.

“Bacteria living in the intestines help to regulate the production of the biochemicals responsible for stimulating neuronal growth.”

Initially interested in the nature of the relationship between the nervous system and pancreatic secretions, Bayliss and Starling discovered that, contrary to long-held orthodoxy, the former did not influence the latter. Instead, it appeared that the pancreas was encouraged to produce digestive juices by chemical messengers that originated in the walls of the intestinal lining, whose communications were delivered through the bloodstream.

Drawing on this research in a lecture to the Royal Society of Physicians in 1905, Starling coined the word ‘hormone’ from the Greek “to arouse or excite” to describe how “activities and growth in different parts of the body” could be stimulated by the excretions of seemingly remote organs. One of the most startling possibilities raised by this revelation was that the rule of the central nervous system – the brain and spinal cord – might be subject to contestation by the remoter principalities of the body.

To test this hypothesis, the collaborators turned to their preferred test subject, a small dog. Having anesthetised and sliced open the dog, the scientists first isolated and disconnected the nerves that linked the intestines with the brain. They then proceeded to inject the animal with hydrochloric acid, which mimicked the effect of gastric movement.

Remarkably, even though the essential nervous connections had been severed, these movements still prompted the pancreas to begin secreting digestive juices. This result demonstrated that the bowel possessed what Bayliss and Starling described as its own “local nervous mechanism”. In other words, the gut could act independently of the brain.

About the contributors

Elsa Richardson

Elsa Richardson is an academic at the University of Strathclyde. She holds a Chancellor’s Fellowship in the History of Health and Wellbeing at the Centre for the Social History of Health and Healthcare. In addition to lecturing in the history of medicine and her own research, she also curates arts and science events for public institutions, including Wellcome Collection. In 2018 she was named one of ten New Generation Thinkers by BBC Radio 3, BBC Arts, and the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.