In ‘Free For All’, Gavin Francis draws on the history of the NHS, as well as his own experience as a GP, to examine the inner workings of an imperfect institution that has transformed the health of millions of people. In this extract, the author and doctor calls for honest conversations about healthcare in Britain and argues why a good-quality national health service for all – provided by everybody, for everybody – is essential.

Why the NHS is worth saving

Words by Gavin Francisphotography by James Glossopaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Book extract

More than 75 years ago Aneurin Bevan wrote an open letter to the medical profession inaugurating the new National Health Service. “On 5 July we start, together,” he wrote.

“There have been understandable anxieties, inevitable in so great and novel an undertaking. Nor will there be overnight any miraculous removal of our more serious shortages of nurses and others and of modern replanned buildings and equipment. But the sooner we start, the sooner we can try together to see to these things and to secure the improvements we all want.”

The spirit of the letter was one of collaboration, though he was aware that there would be problems ahead. “Doubtless other defects can be found and further improvements made,” he wrote, four years after the service opened.

“What emerges, however, in the final count, is the massive contribution the British Health Service makes to the equipment of a civilised society. It has now become a part of the texture of our national life.”

Left: A skeleton named Thomas, after Sir Thomas Browne, watches over the clinic.

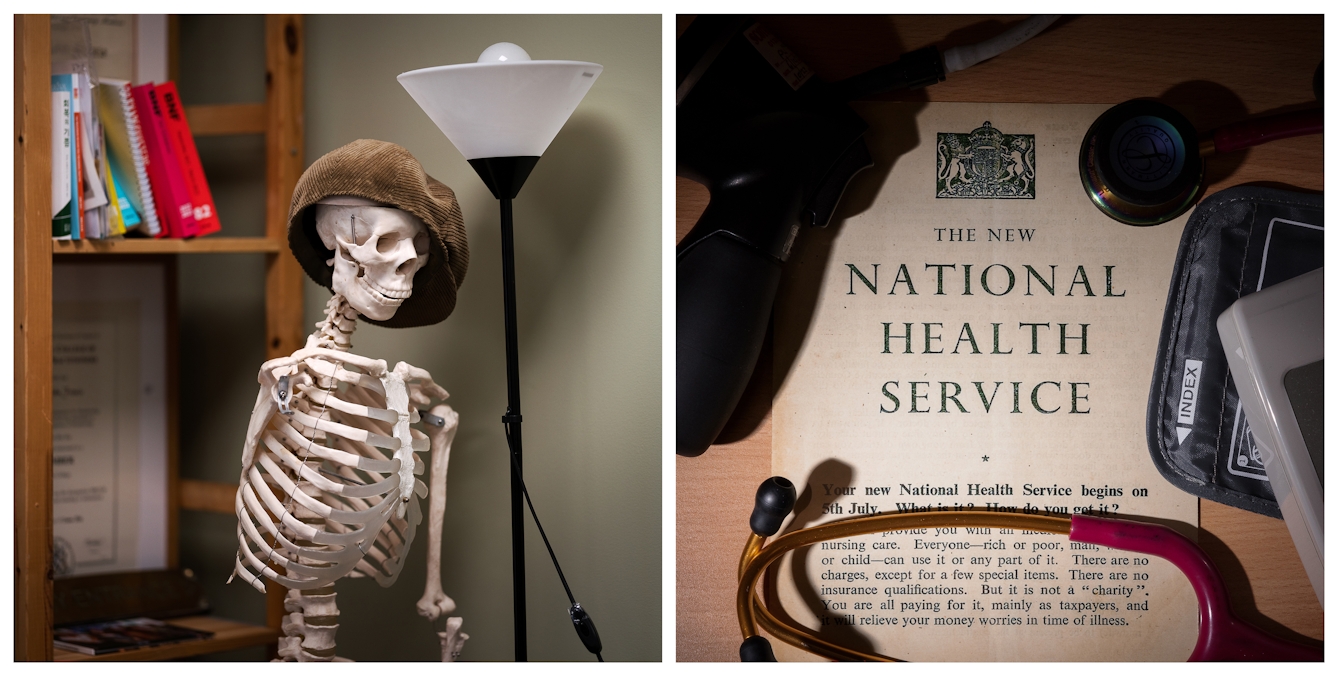

Right: An historical NHS poster Gavin keeps on the wall of his consulting room because it reminds him of the founding principles of the NHS, that no one should fear illness because of an inability to pay for medical treatment.

So how do we save our service? As one consultant physician put it to me: “It’s surely not beyond our wit to come up with a better way.”

Let us honour the principles that established the NHS, a healthcare service that’s free for all, funded by the people, for the people. The alternative is to return to the days of keeping a jar of money aside for doctors’ bills and living in fear of illness.

Find ways of supporting community care, which sees 90 per cent of the patients with less than ten per cent of the funding. People who have known their GP for years and can get a non-urgent appointment to see them have 30 per cent lower admission rates to hospital than those who don’t know their GP – and they live longer too.

Let’s ask our elected representatives to benchmark the NHS against comparable European countries and insist that they commit to funding our service adequately, so that it can keep up. The voters are more unhappy with the NHS than they’ve been for 30 years, so let’s listen to them, and change it for the better. To say that a functioning NHS is unaffordable is to admit to a startling lack of faith in civilised society.

Many front-line clinicians said of the winter of 2022–23 that it was the worst they can remember, and we need to urgently expand hospital wards as well as community care capacity in order to cope with the patient numbers that need help each winter. A system that’s fit only for summer is a system that’s not fit at all.

Gavin taking the blood pressure of a patient in his Edinburgh GP practice.

Democracy and health

Healthcare is people work and it needs investment in people – not only by restoring their wages but also by training them, celebrating them, and trusting in their professionalism. Morale among clinical staff is shockingly low, and there are hundreds of unexplored ways that the mood and working conditions in our hospitals and our clinics could be improved.

The caring professions in Britain right now could do with a bit of care – and some hope. It’s not so long ago that we were clapping them from the doorsteps; let’s now show them some of that support.

The service can’t do all of what is being asked of it right now, so let’s start an urgent national conversation, perhaps through citizens’ assemblies, about what its priorities should be. What can the depleted workforce stop doing to free up capacity and time? How much health promotion can be transferred out of the clinic room and onto TV, radio, billboards? And how much of a drugs budget are the voters willing to support? The current settlement means it’s not possible to have every treatment that every patient might want.

Cherish generalism, and ask of the specialists: what standards are “good enough” to get the best level of care to the greatest number of people? Because by focusing on stratospheric standards in some areas, we have let others fall to appallingly low levels.

A keen cyclist, Gavin rides to see patients in their homes. Edinburgh has an extensive network of disused railway tracks and tunnels that are now cycle paths, meaning many of these journeys can be made away from main roads.

Don’t be fooled by the brochures and promises of private healthcare companies, whose profits are bolstered when the NHS is struggling, even though the service regularly helps them to manage their own failures. Most private doctors in the UK are also NHS doctors, and no one wants decisions about their clinical care made by shareholders.

Clinicians need more time with their patients to have conversations about what the marginal benefits of many treatments really are, and whether giving a formal diagnosis is always appropriate. If we could have honest discussions about the benefits, risks and alternatives to many treatments, there’s a good chance we’d do fewer of them.

In a caring, civilised society, having an ageing population needn’t be a burden, but could instead be something worth celebrating.

Let’s build a network of home-care teams and intermediate-care hospitals that can keep the frail and the elderly away from trolleys on corridors and queues in A & E, finding ways of looking after them closer to home with dignity and compassion.

In the travel bag that Gavin takes on home visits, he carries a raft of equipment which includes a stethoscope, blood-pressure cuff, emergency medications, tendon hammer, tuning fork and urine-testing sticks.

Planetary health is inextricable from individual health: as the NHS recovers, it has to find ways to build back better, with the environmental impact of its buildings and its drugs in mind. Less waste and more efficient buildings save money that can be used for patient care. Mistakes are inevitable in any system of healthcare, and a less litigious way of assessing compensation would help patients who have been harmed, as well as helping clinicians learn from mistakes – and the NHS budget.

Just as journalists should be able to find out the truth of what’s happening in the health service, the health service should be able to depend on reliable and unbiased reporting of its successes as well as its failures. The stakes around the way we talk about the NHS couldn’t be higher – our democracy, as well as the health of almost 70 million people, depends on it.

The most rewarding of jobs

At a teaching session recently at my local medical school, a disconsolate and anxious group of students asked me about falling standards in the NHS, dismal morale among clinicians, and whether there could be any hope for their own careers. “We look at the junior doctors,” one said, “and wonder what it is that we’ve signed up for.”

I told them that 30 years ago, when I started out in medicine, the feeling in the NHS was the same: a burned-out, exhausted workforce was fed up with working in a failing, underfunded service. Patient dissatisfaction was at an unprecedented high when, towards the end of my university training, there was a change of government.

After being based in an old Victorian tenement for decades, Gavin’s practice is now located in a bespoke modern building on the south side of Edinburgh.

The voters demonstrated that they wanted their politicians to put the NHS back to the top of the priority list, and taxpayers’ money flooded in. Morale among doctors, nurses and allied professionals began quickly to rise, and patient satisfaction too; within a few years of the change, studies were being published that put the NHS among the most effective and efficient healthcare services in the developed world.

“The disenchantment in the NHS now won’t last for ever,” I said to those students. “The fortunes of the NHS will improve again – they have to.” I told them that despite all of the challenges of the service as it is today, caring for others remains the most rewarding of jobs; to work in medicine or nursing is to engage your intellect, your curiosity, your humanity, your compassion, and there’s no other job I’d want to do.

The principles on which the NHS was founded are still widely revered – good-quality healthcare for all, provided by everybody, for everybody. Whether those principles can continue to stand up against the costs of a 21st-century world of gene therapy, robotic surgery, innovative biologic treatments and stem-cell transplants, and a population that’s living longer (and with more frailty) than it has ever done, remains to be seen – but I’m optimistic that it can. The alternative is to admit to a lack of imagination and compassion.

A health service free for all at the point of use, based on need rather than on demand, is an expression of what’s best in our society, and we’ll get the NHS we’re prepared to insist on. I hope you’ll agree that it’s worth saving.

‘Free For All’ is out now.

About the contributors

Gavin Francis

Dr Gavin Francis has worked across four continents as a surgeon, emergency physician, medical officer with the British Antarctic Survey and latterly as a GP. He’s the author of the Sunday Times-bestselling ‘Adventures in Human Being’ and ‘Recovery’, as well as ‘Shapeshifters’ and ‘Intensive Care’. He also writes for the Guardian, The Times, the London Review of Books and Granta.

James Glossop

James Glossop is based in North Yorkshire but shoots across the North of the UK and beyond. Most of his work is with The Times newspaper, but he also works with other editorial and commercial clients. An expert in location lighting, he is working on personal projects exploring religion and the British landscape.