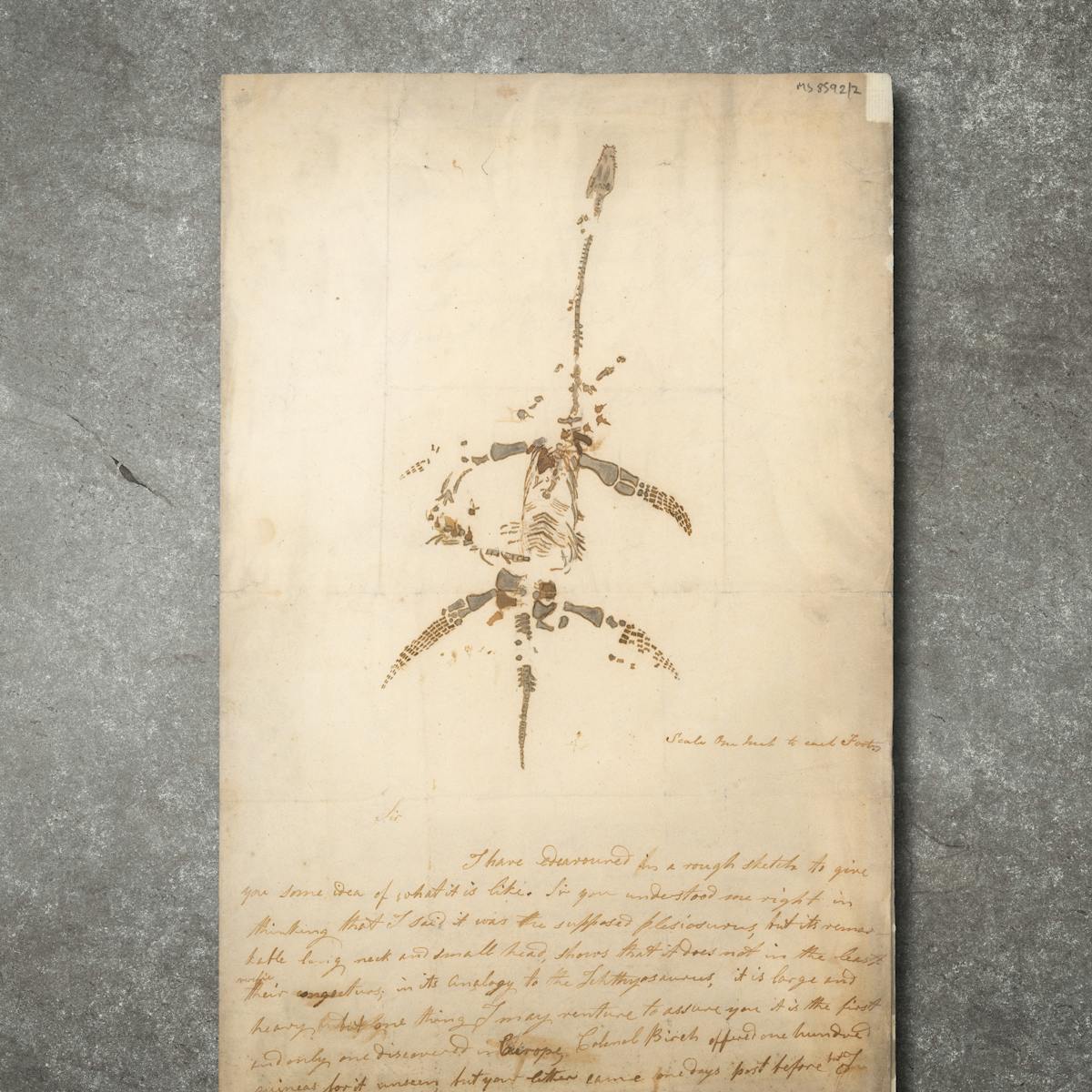

A drawing of the first intact plesiosaur ever discovered, and Mary Anning’s accompanying letters, now preserved at Wellcome Collection, cemented her reputation in the world of paleontology. Although the male-only Geological Society of London attempted to elide Anning’s fundamental role in advancing understanding of the history of the Earth, her important finds – and details from her letters – mean her life and career are still pored over and written about today.

Would you like to buy a dinosaur?

Words by Ross MacFarlaneaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Article

Mary Anning (1799–1847) was an English fossil hunter, dealer and palaeontologist, who was described by science writer Stephen J Gould as “probably the most important unsung or inadequately sung collecting force in the history of paleontology”.

Given the Natural History Museum in London now has the Anning Rooms, and ‘Ammonite’, a feature film about her life was released in 2020, it’s hard to see Anning as ‘unsung’. However, a stronger case could be made that she is still under-appreciated: Anning has long suffered from a romanticisation – and often an infantilisation – of her life. Many accounts focus on her childhood or depict her as a lone woman, shunned by and separated from wider society and a male establishment.

But two letters in Wellcome Collection show that Anning was a skilled businesswoman whose work depended upon her successful connection with others.

A family of fossil hunters

Anning was born and lived all her life in Lyme Regis, Dorset. Her father Richard, a cabinetmaker, developed a sideline in finding and selling the fossils found in the nearby cliffs, and as a child, Mary displayed a remarkably fine eye for making her own fossil discoveries.

Selling locally found fossils was an Anning family business. After the death of her father in 1810, Anning’s mother kept the business going, and her brother Joseph also made significant finds. In 1812, Mary discovered the fossil of what was later to be named Ichthyosaurus, which established her reputation.

In 1820, one of the Anning’s regular customers, Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas James Birch (1768–1829), organised a London auction sale of specimens he had bought from them. The publicity from this sale – buyers for which came from as far afield as Vienna – increased the reputation of the Annings, Mary in particular, as fossil finders; the £400 proceeds from the sale (equivalent to around £49,500 today), donated by Birch to the Annings, increased their wealth.

On 10 December 1823, Anning made her most important find to date – the first complete Plesiosaurus skeleton.

‘The best in all Europe’

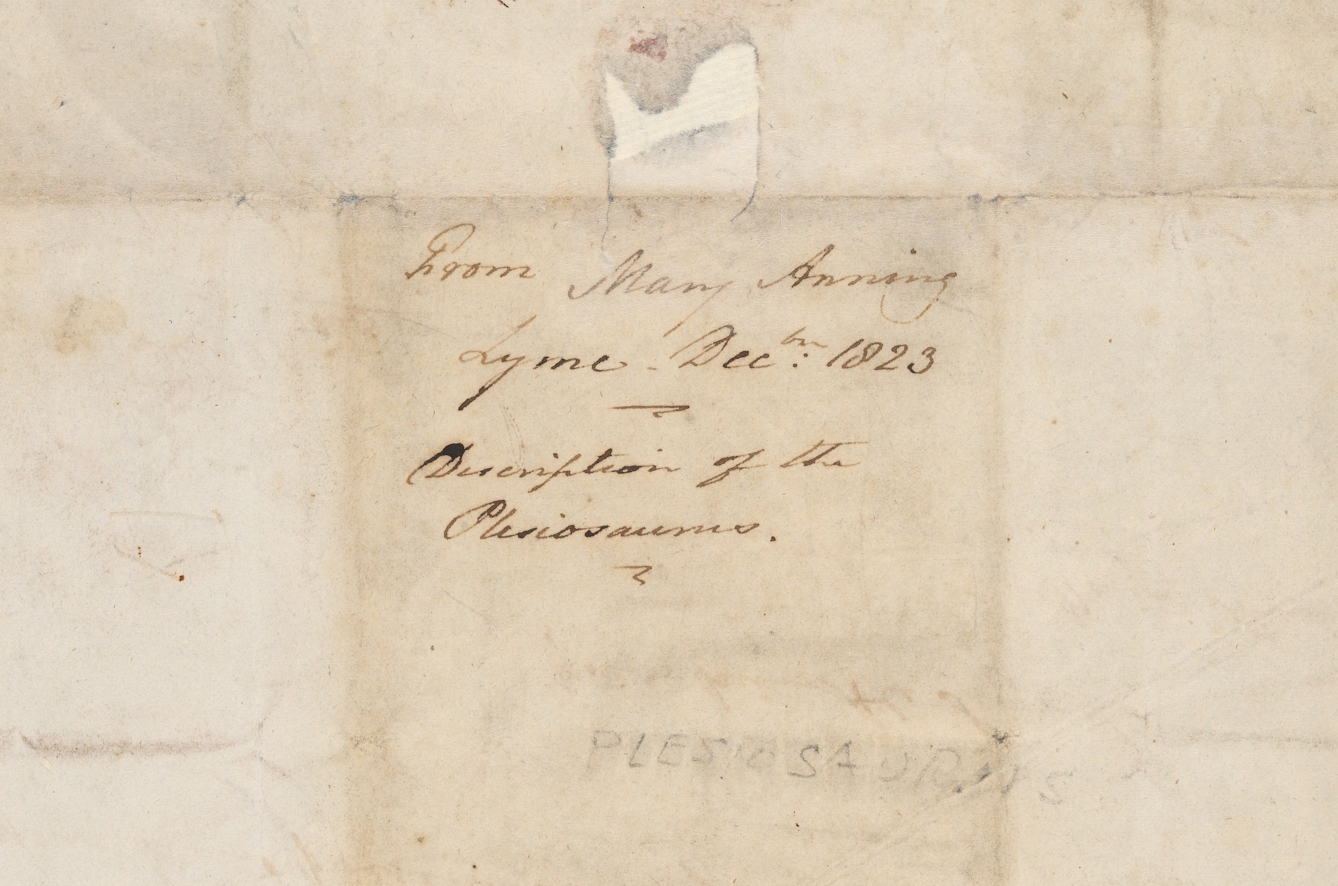

Letters written by Mary Anning are very rare. It’s been estimated that only around 50 letters still survive. This was not because she did not write many, but because her archive was broken up after her death.

The two letters in our collections, and the accompanying drawing, are very precious. They date from December 1823 and describe one of the most important events in Anning’s life: her discovery of a plesiosaur, which cemented her reputation among the emerging international community of geologists and was arguably her most important fossil find.

Anning wrote the letters to Sir Henry Bunbury, 7th Baronet (of Bunbury, 1778–1860). A soldier and historian, Bunbury was noted for his interest in antiquarianism and was an early member of the Geological Society of London.

“Two letters in Wellcome Collection show that Anning was a skilled businesswoman whose work depended upon her successful connection with others.”

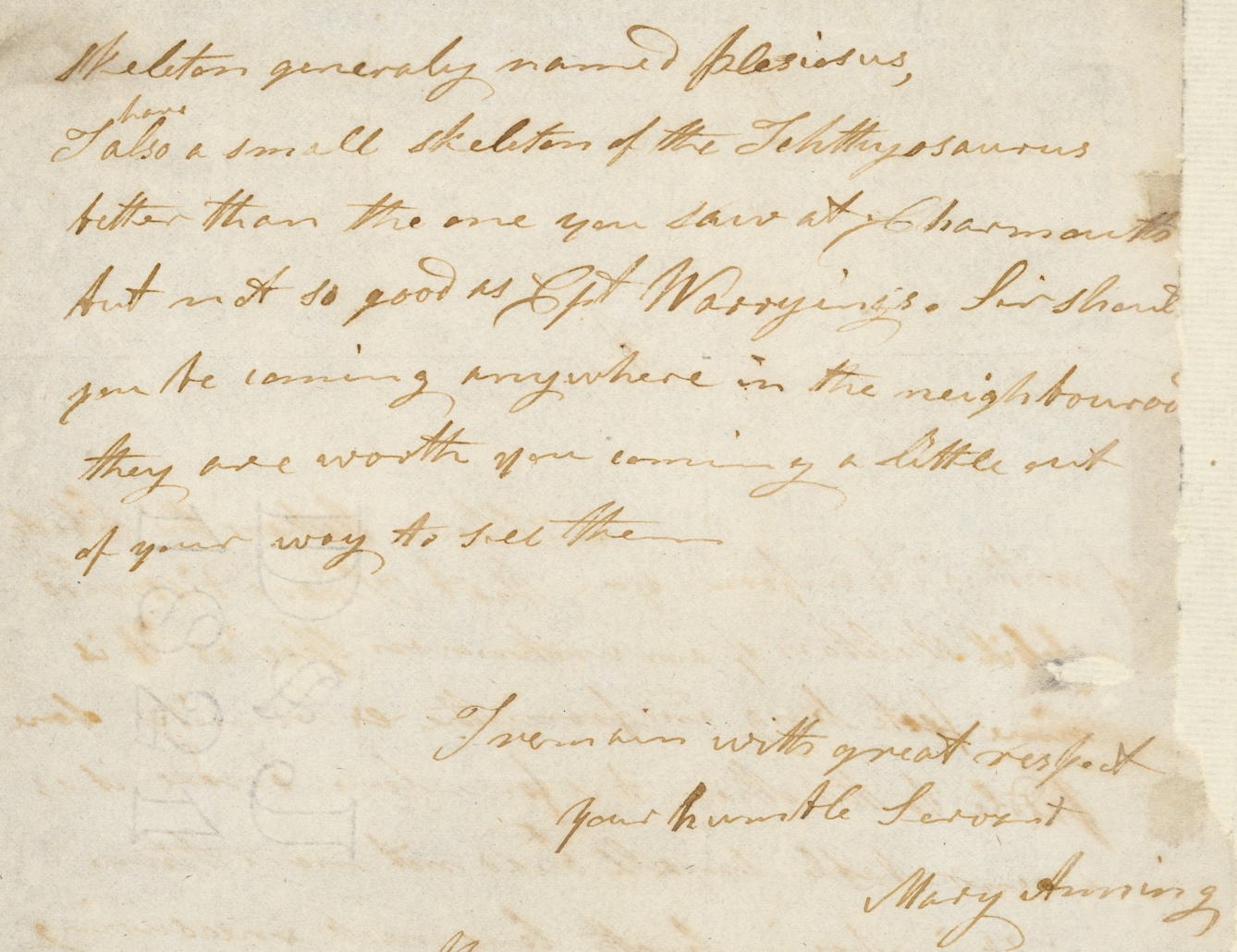

In her first letter – dated 19 December 1823 – Anning informed Bunbury that she had discovered a “skeleton generally [sic] named plesiosus”, giving its measurements and describing it as “the most Curious and illustrative [example] yet discovered”.

Anning also added, “I have also a small skeleton of the Ichthyosaurus better than the one you saw at Charmouth but not so good as Cpt [sic] Warry[ings]. Sir should you be coming anywhere in the neighbourhood they are worth you coming a little out of your way to see them.”

Bunbury must have been a known customer, as Anning knew what he might desire to add to his collection and was targeting her marketing accordingly.

Bunbury evidently expressed an interest in the plesiosaur, as in her second letter to him, Anning added more details – and a drawing of the skeleton. She wrote:

I have endeavoured in a rough sketch to give you some idea of what it is like. Sir you understand me right in thinking that I said it was the supposed plesiosaurus [sic], but its remarkable long neck and small head, shows that it does not in the least verifie [sic] their conjecturs [sic]; in its Analogy to the Ichthyasaurus, it is large and heavy but one thing I may venture to assure you it is the first and only one discovered in Europe, Colonel Birch offered one hundred guineas for it unseen, but your letter came one day past before [but] I consider your claim to be an answer prior to this, Should you like it the price I ask for it is one hundred and ten pounds, one hundred guineas was my intended price, but if take the same sum as Col B offered he would think I had used him ill in not taking his money - Sir I am gratefully obliged to both you and Lady Bunbury for condescending [sic] to think of my favourite he returned to Lyme at midnight quite well I also greatly obliged for your kind present of the [game].

This letter shows how Anning worked as a professional dealer whose wellbeing and welfare depended on her skill in negotiation with men from a higher social standing. She identified the unique selling point of the fossil, noting that its completeness would change what was known of the creature.

Anning justified giving Bunbury first refusal on the basis that he had replied first, but justified asking him for more money on the basis that it would harm her reputation to turn down an earlier offer of sale from Birch.

“In her first letter – dated 19 December 1823 – Anning informed Bunbury that she had discovered a ‘skeleton generally [sic] named plesiosus’.”

Anning’s reference to a present from Bunbury and his wife and, intriguingly, thanking them for thinking of her “favourite” suggests that she had a friendly relationship with the Bunburys that transcended their very different class boundaries. Very little is known about Anning’s personal life, but these letters show that this is not because of secrecy but because of how little of Anning’s writing has survived.

The plesiosaur travels to London

Anning’s letter to Bunbury was one of a number that she sent after her discovery of the plesiosaur. Another was to the geologist William Buckland. Word also reached Richard Grenville, 1st Duke of Buckingham, who eventually purchased the specimen in early 1824 for around £100 (roughly equivalent to £9,795 in 2023). In 1848, the duke sold the plesiosaur to the British Museum, and it is now on display in the Natural History Museum.

Another geologist, William Conybeare, also heard of Anning’s discovery. Conybeare announced the discovery at a meeting of the Geological Society, on 20 February 1824. The announcement was no mere speech: he had arranged for transportation from Lyme to London of the entire plesiosaur skeleton.

The journey was dramatic: the ship carrying the fossil to London from Lyme Regis had become stranded on sandbanks at the mouth of the Thames, and once in London, it took ten men to get the fossil up the stairs of the Geological Society to the room of the meeting.

After completing its risky journey, the plesiosaur was able to attend the meeting. But Anning, its finder – being a woman – was not.

As a woman, Anning would not have been permitted to become a member of the society either, and though the wealthy and influential Duke of Buckingham was named in the published paper version of Conybeare’s announcement, Anning was not.

Anning’s achievements

Yet Anning was not unknown. The plesiosaur was the most important find in her career – it has been described as “the greatest in the eyes of her scientific contemporaries” and cemented her reputation as a fossil finder.

“After completing its risky journey, the plesiosaur was able to attend the meeting. But Anning, its finder – being a woman – was not.”

Anning was credited with the discovery in the local paper, the Western Flying Post. The great French anatomist Georges Cuvier felt the story was too good to be true. He dismissed it, and on seeing a drawing, suggested the find was a forgery on Anning’s part. British geologists – with their patriotism perhaps pricked – rushed to defend Anning and her discovery. Cuvier retracted and later discussed Anning in print.

Anning’s discoveries brought her considerable fame, and she became something of a tourist attraction in her own right, once stating, “I am well known throughout the whole of Europe.”

In her later years, scientific contemporaries acted positively towards her: in 1838 she was granted a special annuity of £25 a year, which was provided via hundreds of pounds raised via the 1835 meeting in Dublin of the British Association for the Advancement of Science and from the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne.

Incontrovertible evidence

The letters themselves demonstrate the professionalism with which she crafted the reputation that has endured beyond her death from breast cancer in 1847.

The fact that Anning’s letters were purchased by Wellcome in the 1930s and catalogued with other “autographed letters” featuring other notable names shows continued respect for her name and work. The contents of Anning’s manuscripts show how her business was intertwined with her personal life and that she was as adept at describing, drawing and promoting her finds as she was at discovering them.

For more about the Anning letters, and other stories, see ‘Women in the History of Science: A Sourcebook’, edited by Hannah Wills, Sadie Harrison, Erika Jones, Rebecca Martin, and Farrah Lawrence-Mackey.

About the author

Ross MacFarlane

Ross MacFarlane is a research development specialist at Wellcome Collection. He has researched, written and lectured on the collections and other topics at the intersection of death, folklore and medicine.