Cecilia Moreno, of the Tachi Yokuts people, tells her story of living in the US’s biggest dairy-producing state, how land has been taken from her people, and her hopes for its return.

How Californian dairy farmers stole a way of life

Words by Cecilia Morenoartwork by Cat O’Neilaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

I grew up seeing a dairy farm every time we visited my family at the reservation in Lemoore, California. I would yell out in the car, “Wow, Grandma, look at all of the ba-ga [cows].”

In the state of California there are more than 1,100 dairy farms, and the largest dairy-producing county in the nation, which has 450,000 milk cows, is in the county that I spent my youth growing up: Tulare County. This is one county away from my tribe’s land, the Tachi Yokuts in Kings County. Therefore the dairy industry has shaped the landscapes I have called home. As a young girl I would have never guessed how much this industry had taken from us or how much land we had truly lost.

According to dairy specialist Virginia A Ishler, “a rule of thumb for dairy operations is 1.5 to 2.0 acres per cow, which includes the youngstock. Even on herds utilising custom heifer raisers, acreage may still be limited for the cows and the reduced heifer numbers raised on the home farm.”

I found that, according to a 1994 study, California dairy herds had on average of 480 cows, while the national average is 60. So, 480 cows times two acres per cow is an average of 960 acres per dairy farm. That is 1.5 square miles.

“As a young girl I would have never guessed how much this industry had taken from us or how much land we had truly lost.”

These numbers just get worse the more you think about it: we have 1,100 dairies in just the state of California, while only 574 Native American tribes in the continental US and Alaska are recognised by the federal government. This is telling a story about priorities and value of land; it is heartbreaking and makes no sense to me.

For us, it is also not just about the loss of our land, our tribe has also lost our pa’aashi (lake).

The dairy colonisers

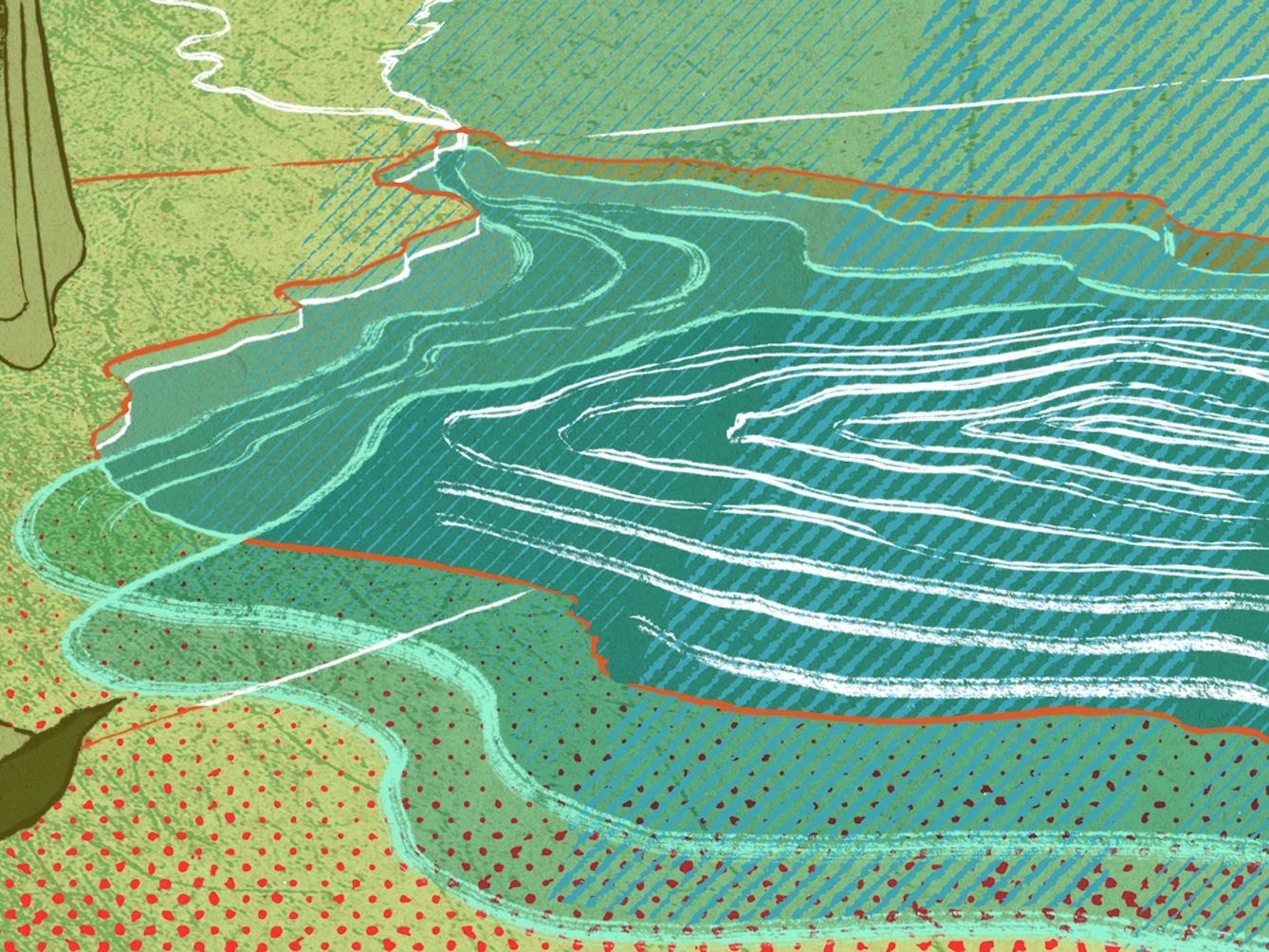

The Central Valley was the home to the largest freshwater lake west of the Mississippi, Tulare Lake. This lake was a place of paradise and the source of life to my people and our neighbouring tribes. My grandmother Lawona explained to me that this land and this lake were very strong and bountiful.

Tulare Lake was a large body of freshwater located by the south-east side of Lemoore. Its area was about 687 square miles (1,780 square kilometres) and provided many resources for the tribes that surrounded it. My grandmother’s people were river people who utilised what the lake provided and established a life that should have lasted hundreds of years, as it was in their ancestors’ time.

But this lake brought a plague to the Tachi Yokut people. It brought men who thought it would be better as farmland.

“This lake was a place of paradise and the source of life to my people and our neighbouring tribes.”

When white settlers drained the marshes surrounding Tulare Lake after the Civil War, they dammed the Kaweah, Kern, Kings and Tule Rivers upstream, and turned their headwaters into a reservoir system. Eventually Tulare Lake dried up completely.

This lake brought a plague to the Tachi Yokut people. It brought men who thought it would be better as farmland.

Draining and damming up all the water resources could turn a profit for them – the lake basin became fields upon fields of crops and dairies. You see rows of green walnut trees instead of the clear blue lake waters. You also see black-and-white cows in numbers that surpass the number of deer and wildlife who drank from this lake.

In the 100-plus years since my people lived at our pa’aashi, we have struggled and come close to extinction. Was it truly worth draining the lake? In my grandmother’s words, “Water is life and there will always be life as long as you care for it. But once it’s gone, it’s gone, and it can never be the same as it was.”

The lake had provided food, materials for shelter, boats, clothing and so much more. This was stripped from us. This was a final colonisation of my people. The Yokuts in the Central Valley were dealing with a form of colonisation from the dairy and agricultural industries, sanctioned and supported by the government.

Hopes for the future

I think back to my youth, sitting in the white truck, driving to the reservation for our Native American language class and remember this powerful saying from my Comitizi Oswick (Grandmother Lawona): “My people were the caretakers of this beautiful and bountiful land. We are the Pa’aashi Yokuts [lake people]. We continue to fight, just as our ancestors did, to survive. The family members who survived all these years ago, we must take on their spirit and continue our cultural and traditional ways.”

“The lake had provided food, materials for shelter, boats, clothing and so much more. This was stripped from us.”

My grandmother was Lawona Fay Icho Jasso; she was a full-blooded Native American. She was Tachi and Wukchumni.

I would hear so many stories of how my people lived and why it was so important to remember all of my grandmother’s stories, because as every elder passed, so did our history. There was disease, and land being stripped away, and my people’s culture, history and lives were dying at a rate which was unspeakable.

But as I wrote in 2018: “It is imperative for the culture to not end with the elders that had experienced such hardships, and for the new generations to quickly learn and preserve these traditions. This will help ensure that the legacy of their tribe may continue into the future.

“My grandmother preserved her culture in her own way by meeting with tribal elders, so she could learn her language and sing their traditional songs. After hearing her experiences and seeing how she embraced her culture, it made me want to work harder to preserve this little piece of history for future generations.”

It brings me to tears because in recent months my grandmother’s hopes for the return of her language and traditions are coming back to us – along with our pa’aashi.

This year in the Central Valley had a record-breaking amount of rain. Mother Nature has blessed us with the water we have been asking for and it has filled our rivers, creeks and waterways, the most it has had in the last few decades. It has brought back our Tulare Lake and had reclaimed 103,000 acres of land by the start of May 2023, with more land likely to be filled with water. This lake, which had been stolen for acres of agriculture and the dairy industry, is finally returning to its natural state.

I know that this return might last only a year or two, but I feel a sense of belonging again. I, and so many other Yokuts Native Americans, have sent our offering to the pa’aashi and our ancestors, hoping that this return will be a great blessing for many more years to come.

About the contributors

Cecilia Moreno

Cecilia Moreno is originally from a small, predominantly Mexican community in the Central Valley of California called Orosi. She is of Yokut and Mexican heritage. Through her maternal grandmother, Lawona, she has learned the importance of keeping native languages and their traditions alive and strives to do so herself by speaking in her native language of Tachi. Cecilia continues to work with Native programmes across California to work towards the revival and preservation of different Native cultures and languages. She currently is a mentor to many Native American students in the Sierra Unified school district.

Cat O’Neil

Cat O’Neil is an award-winning freelance illustrator, specialising in editorial. She studied at the Edinburgh College of Art, graduating in 2011, and has lived in Hong Kong, London, Glasgow, Lyon and Edinburgh. Her clients include the New York Times, Washington Post, WIRED, LA Times, Scientific American, the Financial Times, the Guardian/Observer, Libération and more. Her work explores the use of visual metaphors to convey concept and narrative, and combines the use of traditional and digital mediums. Much of her recent work includes the creation of 3D paper sculptures, which are made in her studio in Edinburgh.