In a few famous 20th-century cases, plastic surgery enabled criminals to remain on the run. But with rapid advances in the accuracy of facial-recognition technology, concealing your identity has become increasingly difficult. Sharrona Pearl, historian and theorist of the face, investigates the issues.

British train robber Ronnie Biggs did it in the 1960s. Columbian drug kingpin Juan Carlos Ramírez Abadía, known as ‘Chupeta’, did it (multiple times!) in the 1990s. But could today’s fugitives from criminal prosecution successfully evade detection through plastic surgery?

Not exactly. Not any more. While London has long led the world in surveillance, with one camera for every 14 residents, other cities and countries are catching up. And while Britain’s massive experiment in exchanging privacy for so-called security has had mixed results at best, the mechanisms are rapidly improving.

Facial-recognition technology (FRT) has become significantly more effective in producing accurate matches between images of people captured by cameras and stored database photos, operating at speed and scale in ways that are only increasing. While the decline in false positives is often hailed as a cause for celebration, given the history of minoritised people being particularly affected by these errors, privacy advocates continue to caution us to be wary not just of mistakes in these systems, but their very goals and structures.

The fact is that surveillance is getting better, which, in the eyes of many, means that surveillance is getting more intrusive. As both private companies and governmental agencies continue to populate our landscapes with identification technologies, advocates continue to ask: is there any way to hide in plain sight?

Finding ways to hide

Let me be very clear: while there are both dubious and legitimate reasons that people may want to evade digital surveillance and detection, I am not, here, interested in examining the ‘why’. Some people, like Biggs and Chupeta (as we’ll see), were hiding from criminal prosecution. Others may be engaged in civil disobedience or seeking asylum or simply wish to guard their privacy or the privacy of others, including schoolchildren and pedestrians.

“Facial-recognition technology (FRT) has become significantly more effective in producing accurate matches between images of people captured by cameras and stored database photos.”

Regardless of the reason, avoiding facial-recognition technology has become increasingly difficult, and – as plastic surgeons and criminal-justice professionals alike are discussing and researching – even plastic surgery won’t necessarily help any more.

There are hacks. Of course there are hacks, ranging from the commercialised and highly instagrammable “computer vision dazzle camouflage”, which uses an array of contrasting colours, geometric shapes and asymmetrical patterns to try to trick the technology, to the more intuitive and time-tested approach of covering any identifiable features with a mask.

The former, which was once somewhat successful, is no longer a match for the highly sophisticated FRT algorithms and has become instead a form of protest (and subject of TikTok tutorials). The latter remains reliable as long as everything is entirely obscured. Even the tips of ears can now be analysed and uniquely identified.

Famous fugitive face-changers

While not quite as old or accessible as a face covering, plastic surgery has been an extreme method to successfully evade identification from both people and technology. When Ronnie Biggs was sentenced to 30 years in prison as punishment for his participation in the 1963 £2.6-million train heist, he was already planning his escape from Wandsworth Prison.

Fifteen months after his admission, he scaled the wall and escaped in a furniture van, heading first to Brussels and then Paris, where he underwent significant face-altering surgery (and spent a big chunk of his stolen proceeds). Biggs’ new face helped him to travel undetected to Sydney, but he was soon identified and was again on the run.

While his new face was now well known, he evaded capture for 36 years more due to his extensive knowledge of extradition treaties (and the lack of them), though he ultimately turned himself in from Brazil in 2001.

Over that time he made a living from his notoriety, recording two songs with the Sex Pistols, posing for photos with tourists in exchange for payment, surviving a kidnapping and ransom attempt, and starring in a documentary about his life and deeds. Biggs’ surgery served to launch him on his life, though he showed no interest in remaining anonymous.

“Plastic surgery has been an extreme method to successfully evade identification from both people and technology.”

Druglord Chupeta began erasing his biometric identify in the 1990s in Brazil, paying officials to erase his fingerprints, images and personal details from the official record. He then, by his own testimony, “had changes done to my face… I altered the physical appearance of my jawbone, my cheekbones, my eyes, my mouth, my ears, my nose”.

He left his compound only at night, and only for bike rides and surgeries, using additional disguises to protect his identity. His alterations were so successful that US federal investigators had to apply for special permission to tap his phone, as they were unable to get a warrant based on visual identification.

Despite Chupeta’s efforts, the voice recognition proved successful and led to the search in which he was ultimately arrested. He then served as a cooperating witness in a 2018 case against another Colombian drug kingpin, Joaquin ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán.

Biggs’ and Chupeta’s surgeries wouldn’t work today. While they may well continue to be effective in protecting people from human identification, the machines work differently.

Most people – with exceptions at either end of the face-recognition spectrum – are mostly good at matching a person to their photo, with error rates between 20 and 30 per cent even among border guards and other surveillance officials. Face-blind people, who are about 2 per cent of the population, recognise no one, and super-recognisers identify almost everyone. Most of us, and most border guards, are neither.

The difficulty of remaining anonymous

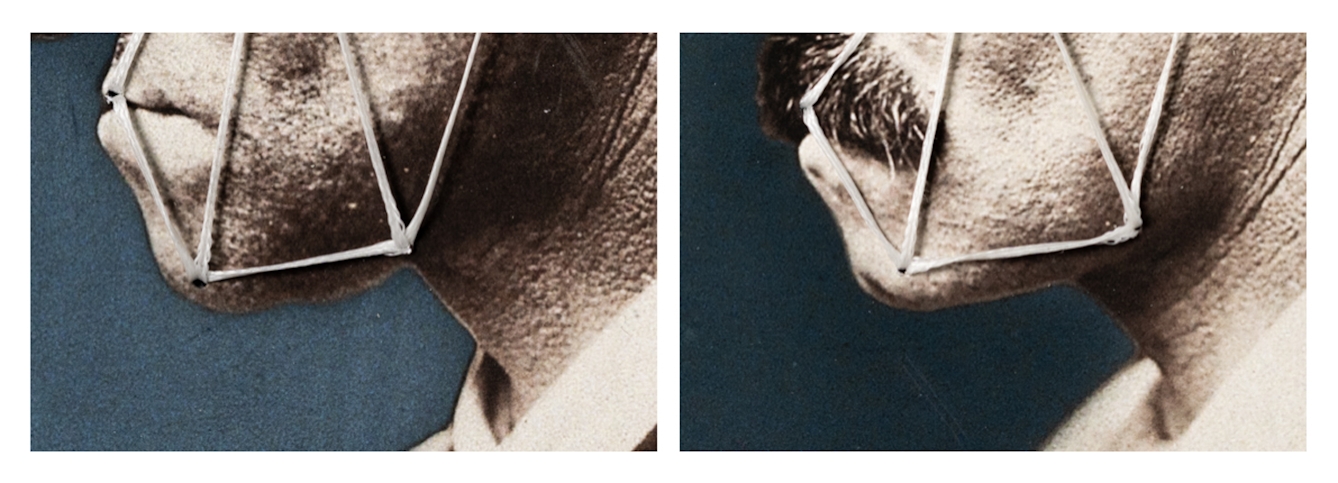

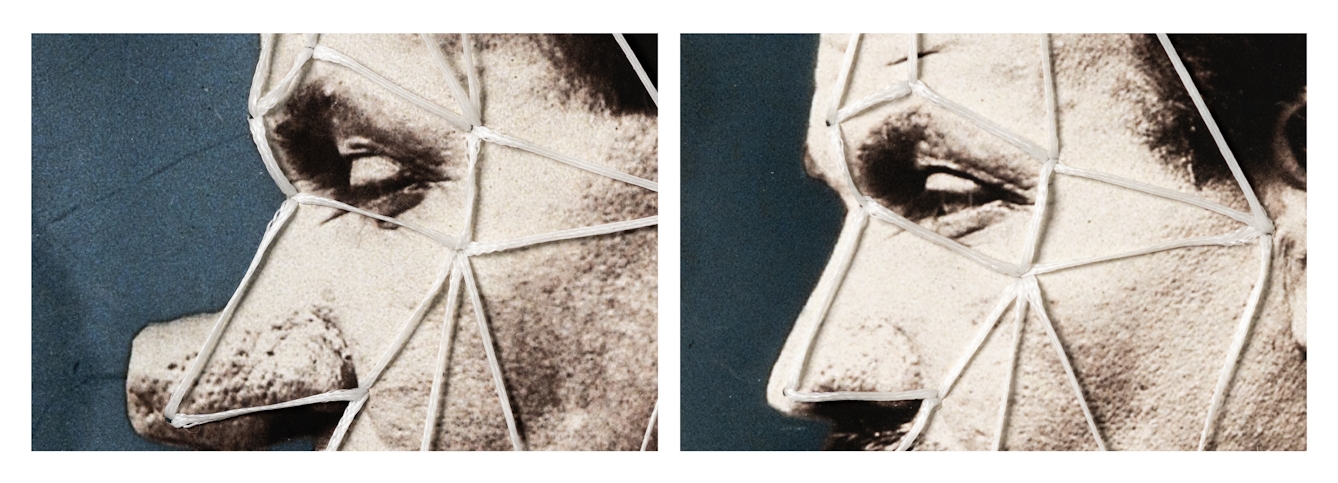

FRT works by turning the individual face into a series of data points unique to the given person and comparing those points to the stored data taken from faces captured online or uploaded as part of governmental records and biometric screenings. The algorithms have become increasingly sophisticated, able to extract unique information from even the most grainy inputs, needing only a scant few features or data points to make a (usually accurate) match.

Most plastic surgery focuses on one feature or intervention, keeping the rest of the facial structure stable and thus still highly identifiable as a series of data points. There are exceptions: to date, operations that fundamentally alter bone structure – thereby changing the distance between data points across the face – render the recipient unrecognisable.

“The algorithms have become increasingly sophisticated, able to extract unique information from even the most grainy inputs.”

These are relatively rare, usually requiring multiple surgeries over significant time. They include all brow corrections and some chin alterations; these tend to come up most commonly as part of facial feminisation surgery, though there are other examples as well. Extreme and sequential plastic surgeries will also create radical change in facial structure, as do partial and full-face transplants.

All of these require significant resources and recovery time, as well as extensive medication regimes and healthcare support. None of them are a strategy for anonymity.

In fact, there aren’t a lot of good strategies any more. Some citizens can perhaps choose not to submit their data to fast-track security lines at the airport; most immigrants and visitors to other countries have already given the government their biometrics. People can opt to navigate the airport in the traditional fashion rather than having their face scanned; that doesn’t mean their faces haven’t been scanned anyway.

As we traverse the streets, the skies and the stores IRL, along with the streets, skies and stores of the digital universe, our faces and bodies and behaviour are being endlessly captured, datafied and surveilled. A scant few may attempt to live off the grid. Others might avoid cameras or strategically cover their features when necessary. These might work at the margins, as too would extreme plastic surgery or ongoing biometric manipulation.

And for everyone else: we can and must establish and maintain systems of governance that support our privacy even as the technology is developing faster that the laws that oversee it, and insist on the fair election of leaders who understand the stakes. As everything becomes identifiable, transparency becomes ever more important.

About the contributors

Sharrona Pearl

Sharrona Pearl is Associate Professor of Bioethics and History at Drexel University. A historian and theorist of the face and body, Pearl’s new book ‘Do I Know You? From Face Blindness to Super Recognition’ is available from Johns Hopkins University Press. Pearl maintains an active freelance writing profile, with bylines in the Washington Post, Real Life magazine, Aeon, Lilith, and more.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.