In her late 20s, Mayanne Soret decided it was time to put her suspicions to rest and phoned her GP for an autism test. But during the year-long diagnostic process, Mayanne realised the assessments framed autistic people as naïve and unlikeable. Here she shares the special things that come from being autistic, and how we might test differently as a result.

I was diagnosed as autistic in my late 20s. It wasn’t a surprise – I’d had my suspicions since early adolescence. What did come as a shock was how dehumanised I felt by the diagnostic process.

When I first called my GP for a referral, I felt pragmatic and optimistic. This was a means to better understand and take care of myself. Yet every step of the way, I found the medical field framed my autism as a problem to be fixed.

There was little space for me to talk positively about my autistic traits, like how joyful and fulfilled my highly focused interests in music, photography and sewing make me, or how my accepting nature has led me to build long-lasting friendships.

Instead, I had to assess myself through the eyes of others: how different I am; how difficult I am to interact with; how uncomfortable I make neurotypical people feel.

‘Definitely disagreeing’ with the first stage of my assessment

I went through the NHS for my autism diagnosis, which uses a number of tools to identify autism spectrum disorder (ASD). One of these is the Autism-Spectrum Quotient (AQ-10). This was the first test I had to complete.

The AQ-10 is used by GPs to assess whether a patient should be referred for a diagnosis. You are asked to respond to ten statements on a scale from “definitely agree” to “definitely disagree”. Each answer is assigned a score, and autism is suspected if your total score passes over a certain threshold.

I sat down to add my answers to sentences like: “People often tell me that I keep going on and on about the same thing.” And: “I know how to tell if someone listening to me is getting bored.” I was confused — what strange statements to rate myself on.

Nonetheless, I sent my questionnaire back and I was referred for a formal diagnosis.

That’s when I began reading more around autism diagnoses, and I found another self-rating test: the RAADS-R. This test is sometimes used by the NHS for more ‘complex’ adult assessments.

Though I didn’t need to take the RAADS-R, I thought it might be helpful to look over. Question 17 read: “Others consider me odd or different.” And question 22: “I have to ‘act normal’ to please other people and make them like me.”

This test felt like it was intentionally trying to hurt me.

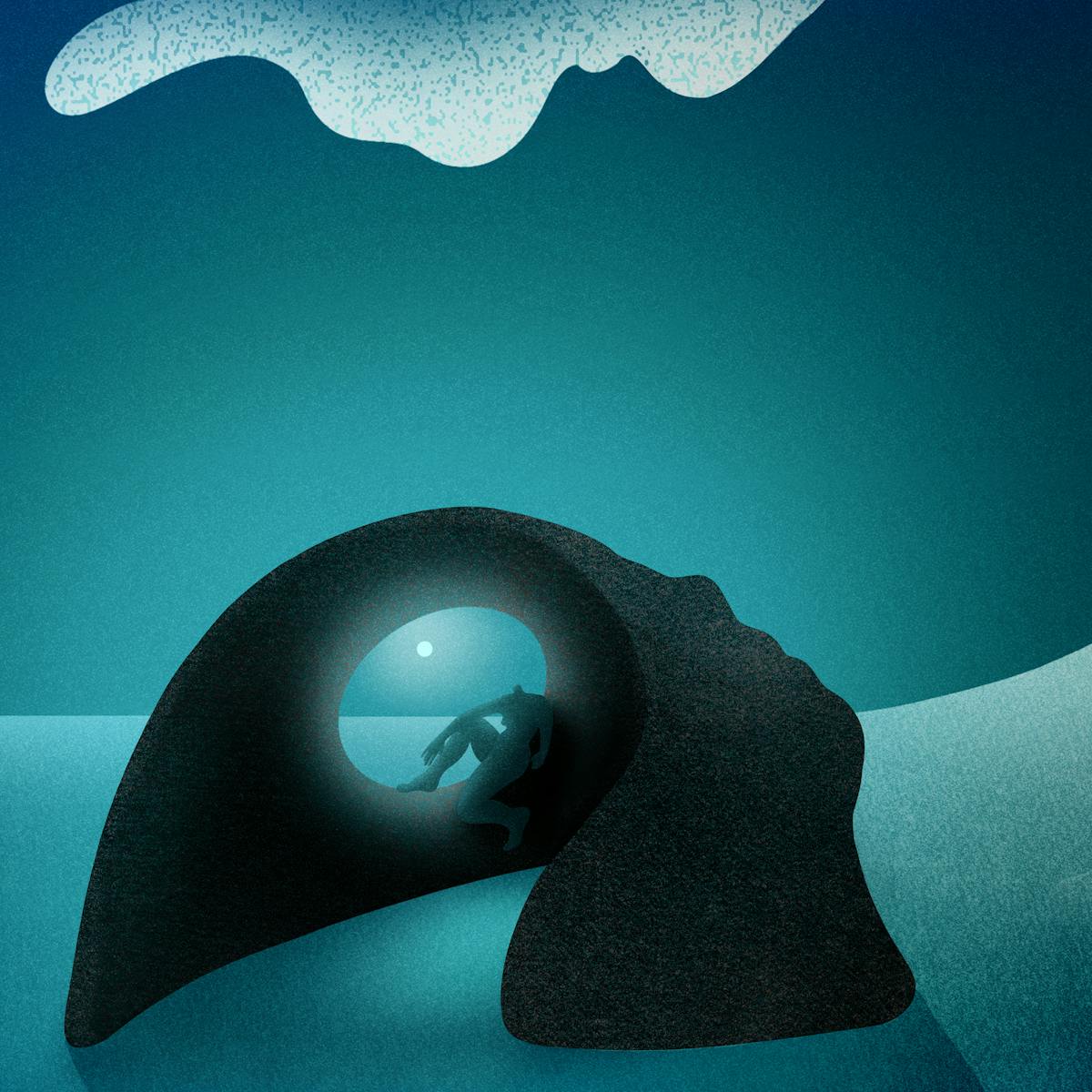

Rogue Wave, 2023.

Statements in both the AQ-10 and RAADS-R portray autistic people as naïve and unlikable. Of course I have struggled to understand social rules in the past, and this has caused me hurt and confusion. But being autistic has also allowed me to connect with others and forge strong bonds. My honest and non-judgmental character has helped me foster close friendships where everyone feels seen and loved for who they are.

Yet seeing those remarks formalised in medical literature gave weight to my deepest fear: that I am a problem for others to deal with.

I was left with shaky self-esteem as I prepared for a crucial next stage: the face-to-face screening.

The exhausting interview process

I had to wait months for my first screening appointment, where I was told a clinician would conduct four sets of one-hour interviews, going over my personal history, behaviours and challenges.

This format is called the Diagnostic Interviews for Social Communication Disorders (or DISCO). It’s a common diagnostic tool for the screening of ASD in adults in the UK.

Since autism affects my communication, I knew it could be a challenge to accurately express my internal reality to the clinician.

I remembered how, as a child, I had often shared with adults all the ways I felt different. But despite my best efforts, no one seemed to understand just how much more different I felt from my peers.

So, I read all I could, from medical literature to essays and memoirs, to find the best ways to communicate my reality.

And although my clinician was kind, the process was painful.

Previously forgotten memories were forced to the surface, and my mind was filled with recollections of abandonment and misunderstanding.

Week after week, I was asked about every aspect of my life I had ever struggled with: how difficult it was for me to make friends, to concentrate in school, to be in busy spaces; how I could become so consumed with my interests that I would forget to eat, wash or sleep.

Previously forgotten memories were forced to the surface, and my mind was filled with recollections of abandonment and misunderstanding.

Rather than focusing on the loneliness and upset of my high-school years, we could have explored how my obsessions with photography and music impacted my life back then. How I spent hours planning photoshoots; how music led me to a group of friends I still have today; how this ultimately gave me the confidence to move abroad by myself.

Trauma did not have to be the only symptom of my autism.

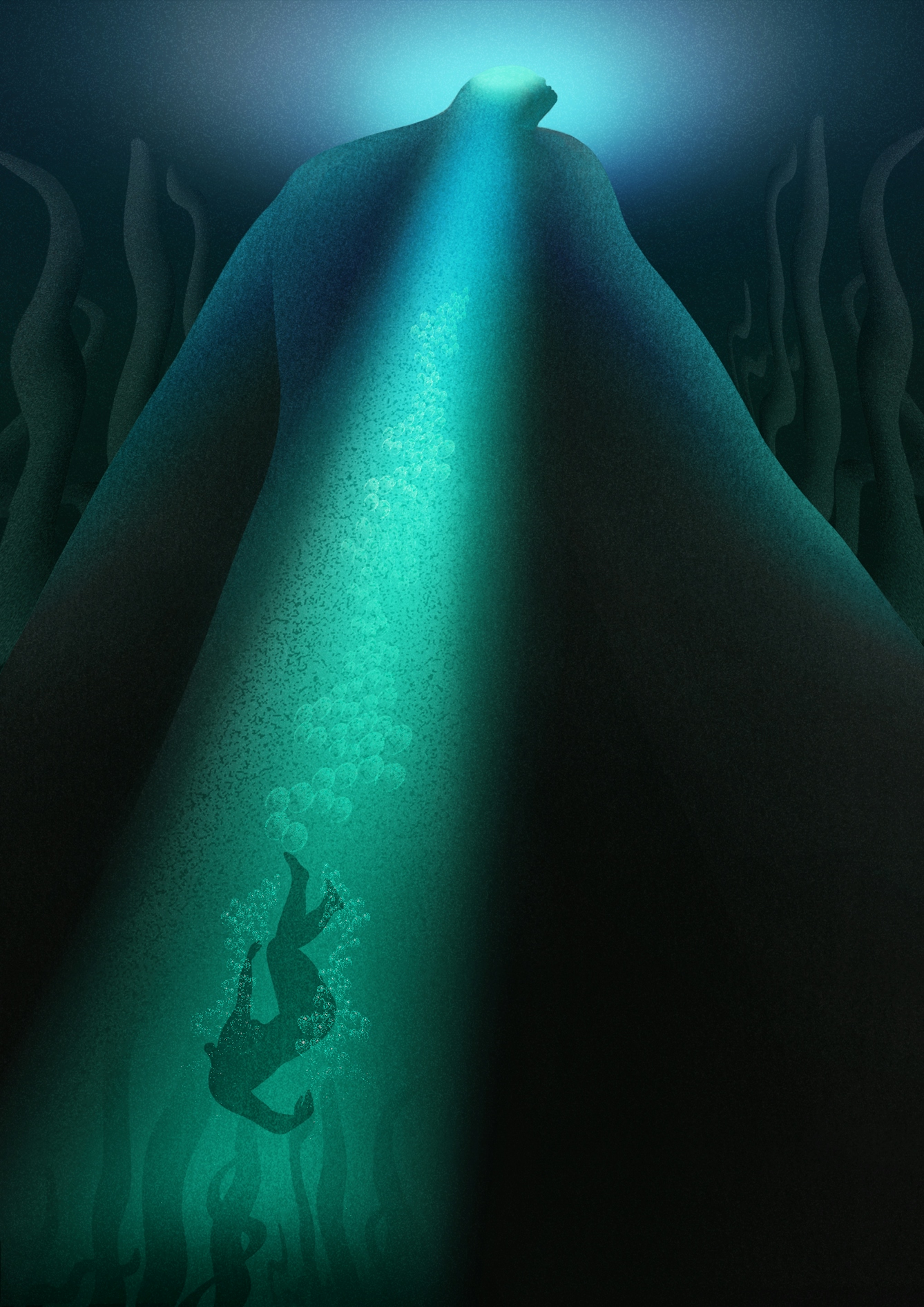

Sea Thrifts and Sympathy, 2023.

Getting some me-centred advice

By the end of the four sessions, I was exhausted, but I still had one more test to go: the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS). There, the clinician asked me to retell a story from flashcards and invent scenarios based on picture books and miscellaneous items.

At the end of the session, amused but a bit confused by what I had to do, I asked the clinician what the purpose of these exercises was. They told me the exam was designed to observe how people process, recall and manipulate new information.

For the first time in my assessment, I was able to discuss how my autism manifests, and how I might make accommodations in my daily life to improve my wellbeing. We discussed the importance of stimming, and how to identify my triggers to avoid sensory overload.

I only got to talk about this because I asked the right questions. I wish more of the diagnosis had involved me like this, and included opportunities to chat informally about my symptoms and personal history.

A call for better assessments

It was a relief to finally receive my autism diagnosis. Not only because my suspicions had been correct all along, but also because this process was finally over.

From referral to result, my diagnosis took over a year: this is the average waiting time for my age group on the NHS. While waiting times for private assessments are much shorter, services often want hundreds for an assessment and hundreds more for medication, mandatory follow-up appointments and other additional costs.

Access to autism diagnosis needs to improve, but so do the procedures themselves. Elsewhere the tests have been critiqued for their male bias and Western-centric perspectives. Both the AQ and DISCO were developed in the UK – the former at the University of Cambridge and the latter at the Lorna Wing Centre for Autism – and the ADOS was created in the United States, yet they are used worldwide. Recent research suggests these may be factors in autism remaining under-diagnosed in certain cultures and communities.

I do not regret going through the diagnosis. I gained invaluable knowledge about myself and others. But I know better assessment practices are needed.

Autism is an integral part of who I am and manifests in many positive ways, but I was not able to showcase that. Instead, the assessment reinforced society’s ableist perceptions of autistic people.

Neither I nor my autism are a problem. There are many ways to be human, and mine is one of them.

About the artwork

The series reflects the isolation and overwhelm felt in both Mayanne’s article and Hayley’s own experience of being diagnosed with ADHD and autism as an adult.

Hayley sees the island as a mask that faces the neurotypical world, and seeks to communicate that while it feels as though there is safety in hiding, there is also sadness and a loss of self. In the aftermath of your referral, you sink into the depths of diagnosis. You fear the memories of trauma you must confront. Like ancient seaweed, it feels as though these painful truths might swallow you in the darkest parts of the sea.

But in time you realise the seaweed is part of your complex beauty. You accept it, move with it, grow with it, and rise to the surface again. The series ends with you stepping out of the mask. And with it is a sense that there is always hope.

Hayley is only just surfacing after their own autism and ADHD diagnoses. They are taking time to reconnect with themself so they can look out to sea in new ways.

About the contributors

Mayanne Soret

Mayanne Soret is a writer based in Edinburgh. Her writing explores visual culture and the politics of digital life. She has written for Dazed, The Skinny, Art UK and The List, as well as independent small presses and zines.

Hayley Wall

Hayley Wall is an artist based in the UK. Hayley’s work highlights the struggles and joys of queer and disabled people as their bodies move through the world. The bodies Hayley draws are often a reflection of themself but can at times express who Hayley desires to be – allowing them new empowering perspectives. Hayley’s hope is that their work might enrich the discourse around marginalised experiences.