With her immigration status uncertain and a threat of deportation hanging over her, Furaha Asani reached out to her church. As an organisation, it failed to provide support. But other churches have provided genuine safe havens for vulnerable migrants, and Furaha argues that this could and should be possible on a much wider scale.

When I was growing up, my family’s various church communities supported one another through celebrations and crises. Now, at the age of 36, I look back at those times with bittersweet nostalgia. These days, I describe myself as a practising non-denominational Christian who is currently non-church attending (for now). I have my reasons for the latter part of this assertion.

When I moved to the UK for my PhD in 2013, I spent some time bunny-hopping between churches, never really settling on one. Regular church attendance became even harder for me after my father unexpectedly passed away in 2016, in my home country (Nigeria), and I took a knock to my mental health and sense of safety. Months into my grief, despite my best efforts in creating a feeling of membership within a church body, I still found it hard to regularise my attendance.

In early 2018 I moved to a new city and decided that I was really ready to make an effort to join a church, and I did. The church was small, and you could get used to every face after three services. The church body had a couple of Black and Brown people, and the leadership made quite a big deal about how happy they were to foster a multicultural community.

I enjoyed post-service chit-chat and the occasional Sunday-afternoon lunch, and I even began volunteering at the children’s Sunday school. Eventually the friendly banter made way for the sharing of more personal information. I actively listened, and also began speaking openly about my mother’s plight as a stateless refugee in Nigeria, my worries about finding a job after my contract ended, and my back-and-forth with the UK immigration system.

When I turned to church in a crisis

In August 2019, things took a turn when I was denied a visa by the UK Home Office. I used prayer request cards, the odd email, and post-service conversations to keep church leaders updated about this escalation of events in my personal life and they assured me I would be supported in their prayers.

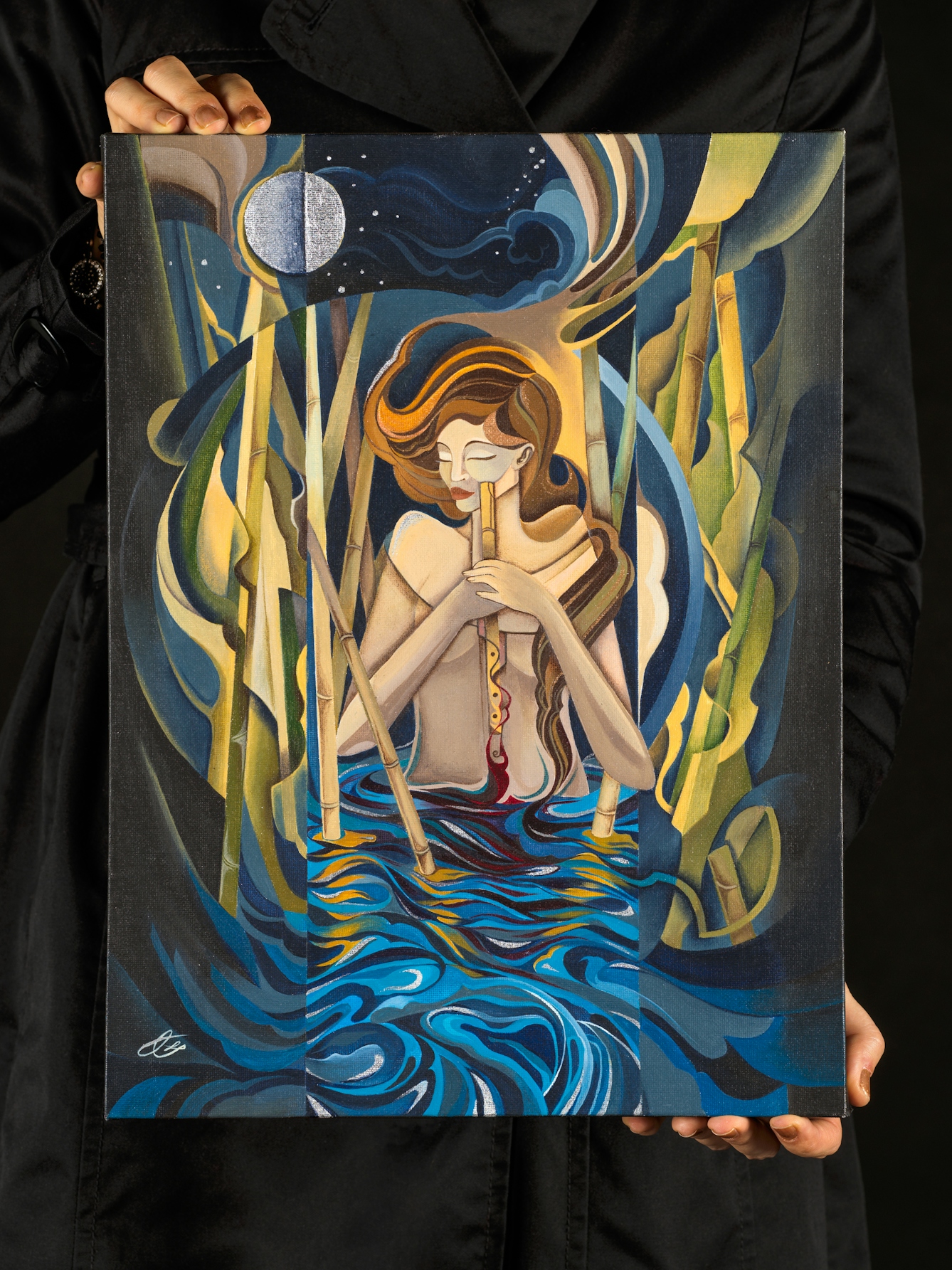

‘Separation from the root’. Acrylic on canvas. 2023. Artwork held by Ghazal Zargar.

When a deportation threat arrived, I began trying to lie low, having major fears that at any point I could be taken to a detention centre. I missed church for more than a month, but except for two Black women friends of mine, no one in this small church body seemed to notice my absence. Or if they did, they made no indication.

My two friends called, cooked food for me, invited me to their respective houses, and prayed over me. I confided in them that the lack of support I was getting from our church, as opposed to the support I knew others had gotten during their own tough times, had made me lose all confidence in this church as a spiritual home. My friends, disappointed, agreed with me, and validated my belief that this treatment (or lack thereof) was racialised.

I’ve never regretted leaving the church that let me down.

I decided to leave that church, but accepted advice from my two church friends and my family to tell the leadership team why I was leaving. I poured out my heart to the church leader. His defensiveness, though disappointing, didn’t surprise me. He didn’t seem to grasp that all I’d wanted was community care. After a tense hour (during which I felt increasing irritation for having served him peppermint tea in my favourite mug), he left. My friend and I ended the afternoon in a bewildered debrief. I’ve never regretted leaving the church that let me down.

Religion and radical support for wellbeing

Radical acts of support by a church are possible, though. In the Netherlands, a three-month unbroken church service helped keep a refugee family safe within the church building. The Bethel Church in the Hague began a church service on 26 October 2018, and kept it going for 96 days with pastors working in shifts. The police were not legally allowed to interrupt the church service to make any arrests of the family, who were resident on the church premises the entire time. In addition to being a spiritual sanctuary, the grounds of that church became a physical sanctuary for that family.

I spoke to writer, activist, and community organiser Dr Keith Hebden – who has also been a church minister – about sanctuary and support from the Church. Hebden’s vast community organising includes work on Citizens UK Sponsor Refugees programme, which since 2016 has seen more than 600 refugees welcomed across over 350 communities through the community-sponsorship scheme.

Hebden also cites various church-run social-action programmes, such as the Safe Passage campaign, Local Pantries, and the Bread Church in Liverpool. Of some of these kinds of social interventions, Hebden notes that implementation usually “comes from the pew, rather than the pulpit”.

This was certainly the case for me at the last church I regularly attended: I found help from the pew.

‘Support and shelter’. Acrylic on canvas. 2023. Artwork held by Ghazal Zargar.

Faith and community health

As my immigration case continued, the Covid-19 pandemic hit. With no NHS access, I was unsure whether I would have access to Covid-19 vaccinations.

Despite the UK government and the NHS clearly stating that anyone, including those with precarious immigration status, should be allowed to register with a GP in order to access Covid-19 vaccines as part of a healthcare amnesty, this did not happen in practice. In July 2021, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism found, in a survey of GP surgeries in England, Scotland, and Wales, that 62 per cent of respondents said they would not register a patient who didn’t have a proof of ID or legal immigration status

As I saw church doors opening to their wider communities and becoming pop-up vaccination clinics, I wondered if any churches were going one step further and providing safe vaccinations for refugees, asylum seekers, undocumented individuals – precarious migrants. Could the Church provide a healthcare sanctuary?

My own networks pointed out that the vaccine providers or the private companies who ran the sites, rather than the churches, would likely make decisions about data-sharing.

I asked Dr Hebden if he was aware of any churches who might have pulled such a radical move. He didn’t know that there were churches that did this but would be surprised if there were none, especially as some churches have always – and never stopped – campaigning on behalf of, advocating for, and supporting the needs of precarious migrants. The Jesuit Refugee Service (JRS) is a faith-based organisation in London that did just this.

Rhiannon Prideaux, JRS’s Accommodation and Emergency Response Manager, explained to me how JRS was able to support some precarious migrants within their network through the administration of 177 first doses of Covid-19 vaccine, followed by 61 second doses and 44 boosters. JRS spoke to their local NHS trust about hosting a vaccine clinic within their centre for precarious migrants registered with JRS.

‘The way of truth’. Acrylic on canvas. 2023. Artwork held by Ghazal Zargar.

While they found that most precarious migrants within their network were already registered with GP surgeries, their aim was to create a safe environment for those who wouldn’t be able to access vaccines – for one reason or another – via a surgery. The JRS team also added on the opportunity for people to speak to legal advisers and caseworkers when they came in for a vaccine. The team held one-to-one chats, and Q & A sessions with doctors online where people were free to air their concerns.

The team also opened up their clinic to precarious migrants not registered with JRS, from another part of London, who wanted to receive the vaccine in a safe environment. “We were really lucky that the health trust was really keen to do outreach. And they didn't just do it with us – they also did it in churches and mosques,” Prideaux adds.

More widely, other organisations have also been campaigning for an end to the hostile environment so everyone can access Covid-19 vaccines safely. James Skinner, Campaigner and Organiser at the charity Medact, told me that most churches he knows of that were offering pop-up vaccine clinics were also ensuring that no one was asked for ID and no information was passed to the Home Office.

“This approach was later replicated by many clinical commissioning groups that organised vaccination drop-in days specifically advertised as no-ID-checking and no-data-sharing days. It's a bit complex for this to be backed up in practice, because once a person's information is in the NHS system, there is a risk it will be shared eventually; however, there wasn't a direct link between vaccination sites and the Home Office that we could identify.”

A place of safety in the hostile environment

I could be considered lucky. I was caught in the UK’s hostile immigration environment for ‘only’ two years and emerged with a visa. I have now been vaccinated (and received two boosters).

Still, I want to see the abolishment of the hostile environment, and to emphasise how urgent it is that every precarious migrant be given safe vaccine access. In my mind, the Church can facilitate this.

It seems to me that ‘sanctuary’ is not any one, static concept, but rather takes many forms. It is my hope to see churches – especially those with resource and capacity – embrace the radical tenets of what it means to genuinely be a ‘sanctuary’ in every sense of the word.

About the artwork

Ghazal Zargar was born in Tehran to an artistic family. Her childhood passion for painting led her to become a graphic designer and illustrator. In 2020, Ghazal was forced to flee Iran, leaving behind her family and the life she had built. Ghazal has now been in the UK for almost a year, as she awaits a decision on her asylum claim. These four paintings symbolise the pain and trauma of her asylum-seeking journey in today’s hostile environment.

About the contributors

Furaha Asani

Furaha Asani is a public academic, mental health advocate, writer, speaker and precarious migrant. Her interests lie in science in pop culture, public and global health, borders and their effects on daily life, and social justice. She has written and spoken on all these issues for several platforms and organisations, and can be found tweeting very unprofessionally as @drfuraha_asani. She has previously written for Wellcome Collection under the pseudonym of Nicole.

Ghazal Zargar

Ghazal Zargar is a painter, illustrator and graphic designer. She was born in Tehran and, for years, taught art classes, designed children’s books and sold her paintings. Ghazal fled Iran after converting to Christianity, as her life was in danger. She finds relief from the stress of exile by focusing on painting and colour. Ghazal dreams that someday she’ll organise an exhibition and sell her work again.

Benjamin Gilbert

Ben is a senior photographer for Wellcome. He is happiest when telling stories with his photographs, whether that be the health implications of rural-to-urban migration in India, or the dedication of the workers who power the NHS.