In 1950, an American journalist popularised the term ‘brainwashing’, arguing that a new amalgam of technology, medicine and ideology was allowing an onslaught on people’s minds. In this abridged extract from ‘Brainwashed, A New History of Thought Control’, psychoanalyst and historian Daniel Pick explores how what we think can be manipulated.

The history of brainwashing

Words by Daniel Pickphotography by Steven Pocockaverage reading time 7 minutes

- Book extract

In September 1950, during the first year of the Korean War, Edward Hunter, an American journalist who had worked in wartime intelligence, and post-war with the CIA, coined (or, more accurately, first popularised) the term brainwashing, and left no doubt for his readers that the problem was important and real. He suggested a profound shift had occurred: new historical conditions existed for governing the mind.

In using the term, first in a piece for the Miami News and then in other writings and books, he was pointing to what he claimed to be a frightening and rising danger. Hunter described a form of psychological intervention that was being perfected by certain enemy states. This involved a veritable onslaught upon people’s minds.

Though he recognised some precursors, he would elaborate during the 1950s upon how the brainwashing threat had truly come of age: a deadly new amalgam of ideology, technology, medicine and psychological sciences that was now transforming social reality in certain foreign places, but potentially in any state.

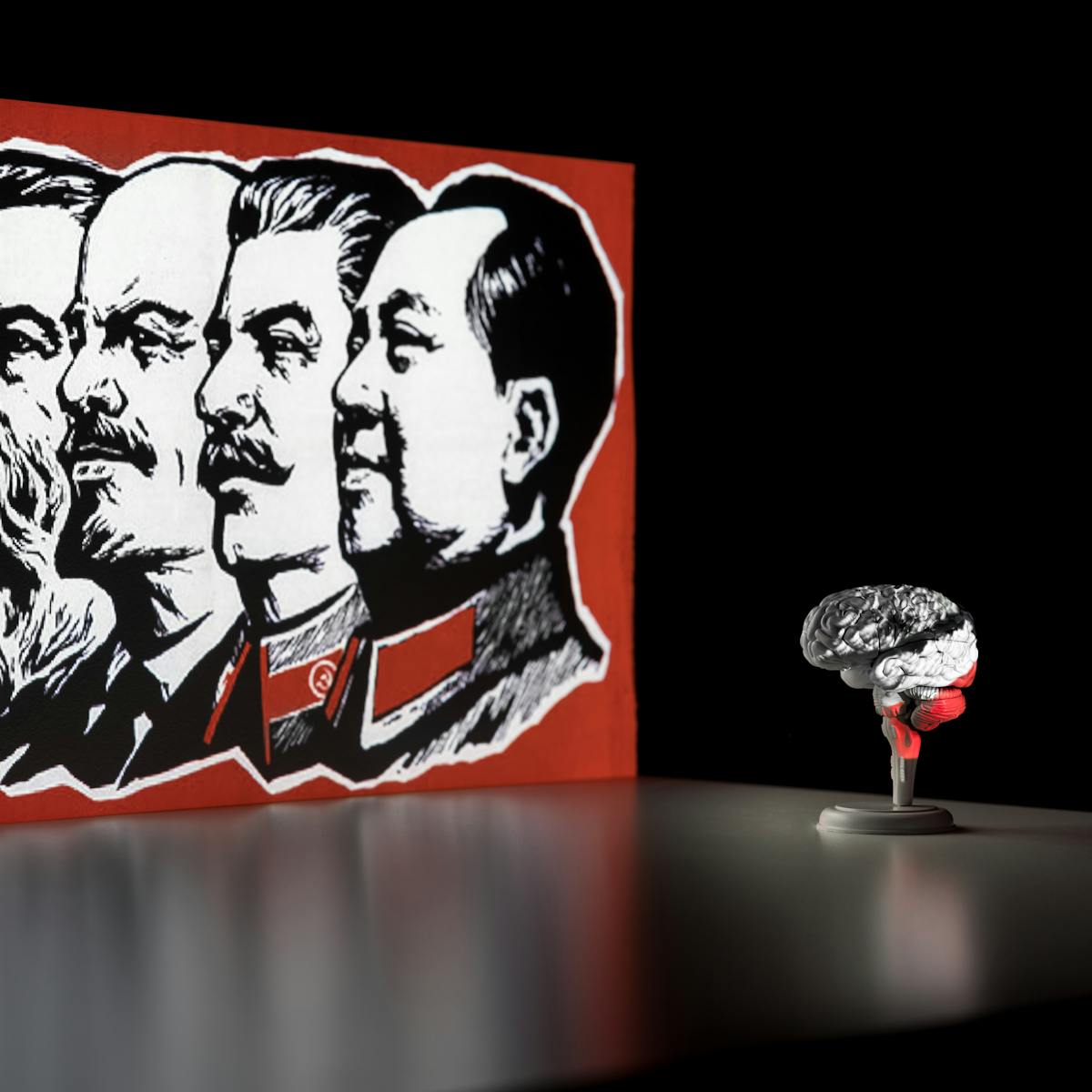

Hunter’s first article, ‘“Brain-Washing” Tactics Force Chinese into Ranks of the Communist Party’, adapted a commonplace Chinese phrase, xǐ nǎo, meaning to wash the brain. That was a euphemism; it was not about cleansing, literally, but rather destroying and substituting. The word’s Chinese provenance was highlighted, and this gave more than a clue to the American’s most obvious concerns: Mao and his communist revolution.

The psychological effects of propaganda

The warnings from Hunter and his fellow 1950s writers about brainwashing found a willing audience, perhaps primed by earlier dystopian scenarios explored in literature – all those compelling accounts of a supine society terrorised by omnipotent masters and/or fed by modern equivalents of ancient “bread and circuses”.

Some writers, such as Aldous Huxley in ‘Brave New World’ (1932), had pictured a future of captivity through anodyne entertainment, sexual so-called liberation, and drugs; others, including George Orwell, whose ‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’ was published in 1949, depicted a world where people are broken and held in a state of permanent totalitarian subjection.

“Hunter described a form of psychological intervention that was being perfected by certain enemy states. This involved a veritable onslaught upon people’s minds.”

By that time, much had already been written in the West about both Nazi and Soviet propaganda warfare. During the First and Second World Wars, substantial efforts were made by both sides to target propaganda efforts more efficiently, and, increasingly, to monitor shifts in morale and public opinion.

Clinical expertise was sought and deployed in the efforts during the 1940s to analyse and redress the deep psychological and social consequences of Nazism. The Nazis, after all, had sought to recast the population; they used the term Gleichschaltung (translated variously as coordination, synchronisation or consolidation) to convey the ambition to refashion society across the board.

The aim of the Nazi Party was to shape profoundly not only politics, but also every facet of society, and, ideally, to end all opposition in the minds of the people: in sum, to achieve a total harmonisation. It was never fully realised, but the German people lived for 12 years under the Führer; millions had voted for him, fought for him, agreed with his aims, loved him and accepted his world view, even in the face of impending calamity.

During the Second World War, psychological and anthropological researchers, including psychoanalysts, worked for the Allies in the army and intelligence services. They attempted to understand the mass appeal of fascism and the psychological consequences of living under such modern forms of tyranny; they would also help with assessing the testimony of POWs, refining propaganda, mounting “dirty tricks” operations, seeking to decipher the deeper intent and impact of enemy broadcasts, and, after victory in 1945, assisting the victors’ efforts to ‘denazify’ a defeated German population.

A focus on the brain-invaders

That terrible history continued to shadow Cold War debate on brainwashing. At the same time, there were dramatic developments in neuroscience and the elaboration of ‘psycho-surgery’. Some pundits heralded the great advances made in mental health treatment for all, thanks to the advent of electric-shock therapy and new techniques of brain surgery.

By the 1950s and 1960s, some surgeons, including prominent figures notably in the United States and Britain, would make grandiose claims that they could cure or tame those who were presumed to be suffering severe and chronic mental disorders by conducting lobotomies.

But if medicine and science might claim jurisdiction and have a key role in fixing pathological conditions in brains, from cancerous tumours to schizophrenia, others feared that drugs, shocks and surgery could also facilitate new modes of social control, including the pacification of the troublesome, unhappy, disturbed and eccentric inside a supposedly liberal society.

“If medicine and science might claim jurisdiction and have a key role in fixing pathological conditions in brains, others feared that drugs, shocks and surgery could also facilitate new modes of social control.”

Post-war movies updated older conceits in the mode of Frankenstein, featuring white-coated technicians who invade brains.

Such debate about the advances and potential dangers in science, medicine and technology also profoundly shaped the language of brainwashing. Post-war movies updated older conceits in the mode of Frankenstein, featuring white-coated technicians who invade brains, even perhaps entirely rejuvenating and controlling minds and bodies.

At the same time, some analyses of totalitarianism focused on the potential role of medicine and psychology in helping the state to ensure compliant or enthusiastic states of mind in a captive population, be it for fascism or communism.

Resisting brainwashing

Hunter wanted Americans to know that brainwashing threatened them too. He offered readers anxious glimpses of how in this new epoch, medico-psychiatric programmes could be unleashed with alarming rapidity. The methods might be overt or practically invisible. He saw links to the past, but also differentiated this emerging period of history sharply from earlier ages, when other, varied techniques exerted by political movements, religions, parties or states won hearts and minds.

The question for Hunter was whether the prisoner/patient in latter-day regimes such as Stalin’s or Mao’s could ever resist, and what tools could be offered to make people more wary, critical and resilient. Hunter recognised the possibility of psychological resistance, and explored more gradations than these simple absolutes.

Whatever the rhetoric, his accounts begged more questions than they answered, not only about how best to meet the challenge, but also about how brainwashing could be isolated conceptually from other ideas about education, persuasion and influence. His writings suggest the modern origins of the word; the mixture of fascination and fear the process evoked; the dramatic pictures so often painted, and yet also the blurred edges of that Cold War debate.

“People had to evaluate the stories they were being told and assess the authority of the columnists who told them what to think, where the dangers were coming from, whom to fear or how to resist.”

Was the procedure so total and indelible? Where and how might people hold out? What about partial brainwashing, split convictions, half-hearted conversions and milder forms of pressure and cajoling?

His role as a journalist and pundit on brainwashing was also significant, for much of this debate would be conducted not in seminar rooms or in parliaments, but across the airwaves, in popular magazines, newspapers, on TV and in the cinema. People had to evaluate the stories they were being told and assess the authority of the columnists and opinion-makers who told them what to think, where the dangers were coming from, whom to fear or how to resist.

Knowledge is power

When it came to describing what forms brainwashing actually took, and explaining the precise mechanisms involved in the process, Hunter reached for metaphors and analogies that, far from pinpointing the science, in fact made it seem truly scary, and also tantalisingly vague; for brainwashing, he proposed, somewhat loosely, is “more akin to witchcraft with its incantations, trances, poisons and potions”.

The whole thing “was a mixture of old voodoo as it were but all with a strange flair of science about it all… [a] magic brew in a test tube”.

Mysteries still abounded; he said the Chinese tried to cover up what they were doing. They didn’t want to call it brainwashing, even though they knew, apparently, that was precisely what it was. The first requirement, in Hunter’s view, was to identify the methods of brainwashing and then explore what would help people to withstand the assault.

To work most effectively, the process, he proposed, depends above all on the subject’s ignorance of how it is conducted; so, to educate might also be to arm us. If brainwashing could overpower free will, a well-prepared mind and well-equipped society could – maybe – push back against dangers abroad, or here in its midst. On the other hand, the brainwashers were becoming ever more sophisticated, and perhaps a day would come when resistance was futile; but then again, maybe not…

‘Brainwashed’ by Daniel Pick is out now.

About the contributors

Daniel Pick

Daniel Pick is a psychoanalyst, historian, university teacher, writer and occasional broadcaster. He is Professor of History at Birkbeck College, University of London, a fellow of the British Psychoanalytical Society, and author of several books on modern cultural history, psychoanalysis, and the history of the human sciences.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.