When your heart suddenly stops pumping blood around your body, the consequences can be life-changing, if not fatal. It’s somehow especially shocking when the cardiac arrest happens to someone who is young and fit – like the Danish midfielder Christian Eriksen. Here Meg Fozzard draws on her own experiences, and those of a fellow cardiac-arrest survivor, Tim Butt, as she discusses why some young people’s hearts stop, and why it seems to affect sportspeople more.

In the 42nd minute of the Denmark versus Finland match, during the delayed Euro 2020 football tournament, Danish player Christian Eriksen suddenly collapsed on the pitch. I was at home, watching the match on television. Alongside viewers from around the world, I saw Eriksen’s teammates huddle around to shield him from the cameras as he received CPR.

I had a cardiac arrest in 2019. I, of course, can’t remember what happened, but seeing someone else go through what I experienced was upsetting. I instantly thought of my boyfriend and how time must have stopped for him as he performed CPR on me.

After 15 minutes the match was suspended, Eriksen was carried off on a stretcher and both teams headed to the changing rooms. What felt like an agonising amount of time later, it was confirmed that Eriksen was awake and responding, and the match resumed.

It was unlike any game of football I had ever seen before. It was a very emotional time, with UEFA President Aleksander Čeferin saying, “Moments like this put everything in life into perspective. Football is beautiful and Christian plays it beautifully.”

Cardiac Risk in the Young (CRY for short) were quick to comment. The charity’s chief executive, Dr Steven Cox, described Eriksen’s collapse as a reminder of the impact cardiac conditions have on young people aged 14 to 35. Cox explained that, every week in the UK, “At least 12 apparently fit and healthy young people will collapse and die suddenly from previously undiagnosed heart conditions.”

“Sport itself will not actually cause sudden cardiac death, but it can significantly increase a young person’s risk if they have an underlying condition,” Cox went on to say. What happened to Eriksen was a “terrible reminder that even the young and fittest in our society are at risk”.

An everyday event

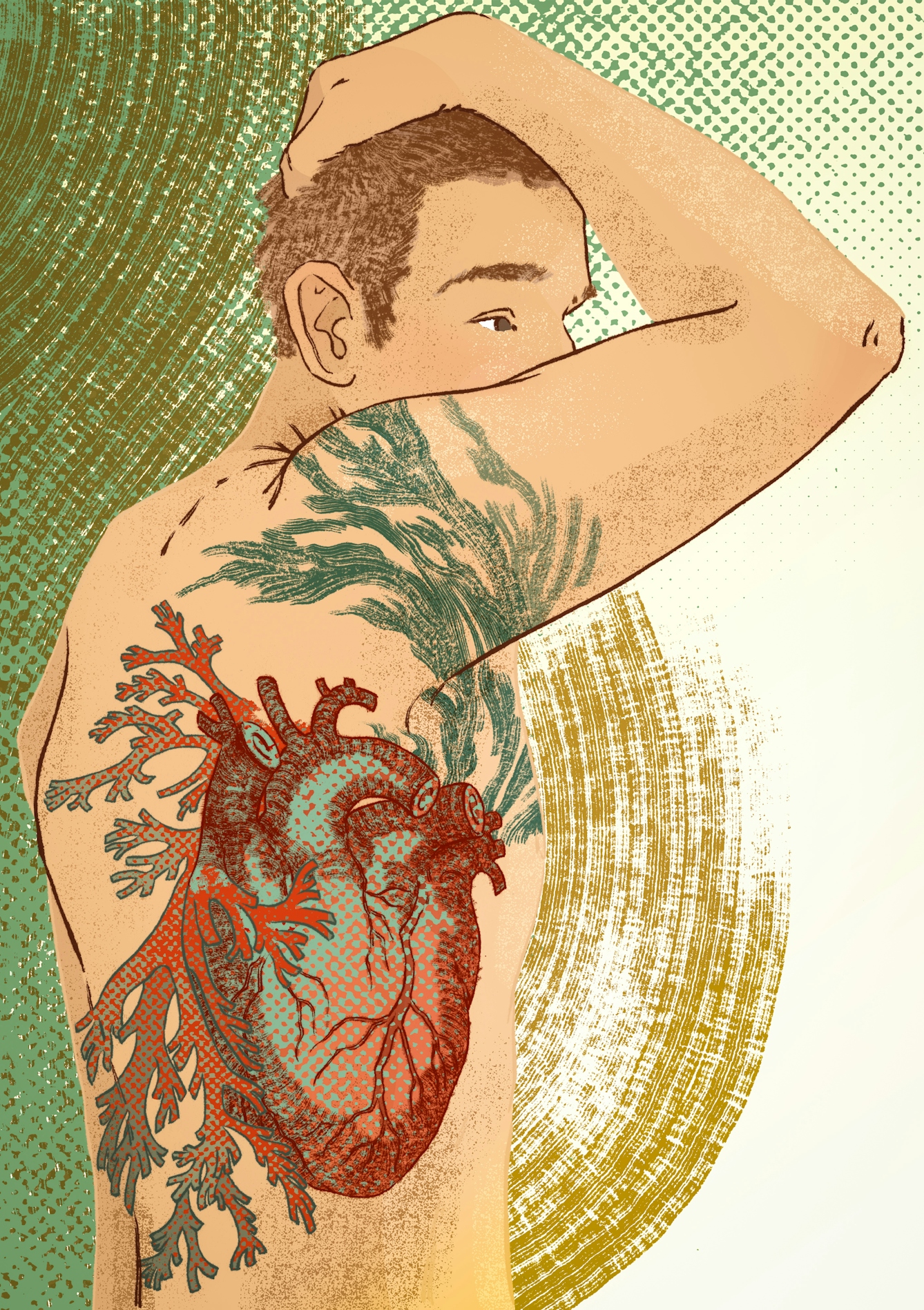

Many people conflate a cardiac arrest with a heart attack, but the two are different. A heart attack is when one of the coronary arteries becomes blocked, whereas a cardiac arrest is when a person’s heart stops pumping blood around their body and they stop breathing normally.

High-profile cases like Eriksen’s draw attention to cardiac arrests in the young, but they happen to everyday people all the time.

“Many people conflate a cardiac arrest with a heart attack, but the two are different.”

High-profile cases like Eriksen’s draw attention to cardiac arrests in the young, but they happen to everyday people all the time. Tim Butt had a cardiac arrest when he was 23, completely out of the blue.

“I classified myself as an athlete for about ten years. I was regularly training with a heart-rate monitor and would say I knew my heart well: things like my resting heart rate, max heart rate and lactic threshold. I was in tune with my body but never suspected any heart problems,” Tim told me.

“Sadly, I was aware of a schoolfriend that suffered a cardiac arrest while playing football and had died earlier that year. That made me stop and think, but what can you do? Not once did I have any symptoms or suspect an issue, and I continued my life, sport and training as normal.

“The day before my cardiac arrest I had raced my bike over at Redbridge Cycle Circuit and felt good, finishing strong on the uphill sprint in an elite field of riders. I then headed to a family gathering before going for a few drinks with friends later that night.”

Sport had been a large part of Tim’s identity before his cardiac arrest. “It was pretty obvious, having been told that I had suffered a cardiac arrest, that my previous level and intensity of participation in sport would not be recommended,” he told me.

“It’s been a journey since then: denial; turning away from cycling at times altogether; doing more sports coaching; finding other sports and new levels of expectations and satisfaction. I’m never going to get any personal-best times or be able to train hard again, but I can enjoy participating in sport and make my own decisions when assessing the risk and reward of doing so.”

Working out who’s at risk

Like Tim, my life changed completely when I had a cardiac arrest. I had flown home from a family holiday in America the day before and taken the day off work because I didn’t feel 100 per cent. Luckily, when I went into cardiac arrest, my boyfriend and housemate were there, and my boyfriend had done some CPR training years before.

I was by no means an athlete, but I regularly did pole dancing and aerial hoop to keep fit. My cardiac arrest led to a brain injury, which means I now have issues with balance and coordinating, ruling out these activities. I had to delete all my posts on Instagram of me doing aerial hoop and pole dancing because it was too difficult to look at.

“My life changed completely when I had a cardiac arrest. I had to delete all my posts on Instagram of me doing aerial hoop and pole dancing because it was too difficult to look at.”

I spoke to Dr Hamish MacLachlan, who specialises in sport cardiology and collaborates with CRY. He explained that we tend to assume that sudden cardiac deaths predominantly affect professional athletes, but it’s probably just that their cases are high-profile and attract media attention.

There are statistics showing the risk of sudden cardiac death for competitive sportspeople in Italy, where cardiac screening is mandated by law. “Early data from these screenings suggested that athletes were about three times more at risk from sudden cardiac death compared to non-athletes,” MacLachlan told me. “However, data from France and Denmark has actually suggested that there is very little difference between the risk profile of athletes and non-athletes.”

MacLachlan emphasised that it’s “incredibly important to recognise that sport per se is not the direct cause of sudden cardiac death in athletes; rather, it acts as a trigger for sudden cardiac arrest in individuals that have silent cardiovascular disease”.

There are strict rules regarding cardiac health and sports in Italy. Before his cardiac arrest, Eriksen was playing for Inter Milan, but last year they released a statement saying that the Italian medical authorities have banned him from all sporting activity.

Eriksen has now moved to play for Brentford in the Premier League, where no such rules exist. Brentford have said that, “In order to respect Christian’s medical confidentiality, we won’t be going into any details. Brentford fans can rest assured that we have undertaken significant due diligence to ensure that Christian is in the best possible shape to return to competitive football.”

For Dr MacLachlan, high-profile cases like Christian Eriksen’s galvanise discussions about who’s at risk of cardiac arrest. However, he’s careful to remind me that “the majority of conditions that cause sudden cardiac arrest or sudden cardiac death are hereditary (so the result of a faulty gene) or congenital (an issue with the development of the foetus). For that reason, the prevalence of these conditions is no different in the population of athletes versus non athletes.”

The urgent medical care that Eriksen received saved his life and his career. What happened to him was horrific to witness, but it did highlight the importance of knowing how to successfully administer CPR. In fact, it sparked a 1,000 per cent increase in calls asking for resuscitation training. It also helped draw attention to cardiac screening programmes for young athletes.

Whether a cardiac arrest occurs on or off the pitch, public awareness of correct CPR is crucial. Many, many young people are not as fortunate as me, Tim and Christian.

About the contributors

Meg Fozzard

Meg Fozzard is a freelance journalist and producer who mainly writes about disability issues. She can often be found trying to put the non-disabled world to rights on Twitter and Instagram.

Cat O’Neil

Cat O’Neil is an award-winning freelance illustrator, specialising in editorial. She studied at the Edinburgh College of Art, graduating in 2011, and has lived in Hong Kong, London, Glasgow, Lyon and Edinburgh. Her clients include the New York Times, Washington Post, WIRED, LA Times, Scientific American, the Financial Times, the Guardian/Observer, Libération and more. Her work explores the use of visual metaphors to convey concept and narrative, and combines the use of traditional and digital mediums. Much of her recent work includes the creation of 3D paper sculptures, which are made in her studio in Edinburgh.