Growing up, Catriona Reid carefully hid two things about herself: she’d been diagnosed with Asperger syndrome, and she was taking Rigevidon, an oral contraceptive, to treat acne. As an adult, she began to question the negative effect her medication was having on her mental health, but found it hard to be believed. Here she shares her experiences of the pill as an autistic woman.

I was 14 when I was first prescribed Rigevidon as an acne treatment. It’s a combined oral contraceptive containing oestrogen and progestogen. I didn’t think or talk about it much at the time because I wanted to hide the fact that I was taking the pill. Being prescribed a contraceptive at this age felt ‘unseemly’. In my mind, it automatically advertised I was having sex. Although I was not, the idea that people would think this was terrifying. I dreaded being branded ‘a slut’.

I also wanted to hide something else about myself: that I was autistic. I was diagnosed with Asperger syndrome when I was two. Growing up, I always knew I had autism, but I chose to conceal it.

In school, I remember people saying someone was acting ‘autistic’ when they were upset, angry or being stupid. I heard this, internalised it, and did not tell anyone outside of my closest friends about my diagnosis until I went to university.

I left high school in Scotland after fifth year, rather than sixth, and started university when I was sixteen. I was younger than everyone else I knew there, but I made friends with girls that lived in my halls. We grew close enough to talk about things like sex, relationships and contraception.

Almost all of them had been prescribed Rigevidon as their first contraceptive but changed to other methods because of the side-effects. I kept taking it but slowly realised that I was experiencing similar side-effects, and more.

"Growing up I always knew I had autism, but I chose to conceal it. In school, I remember people saying someone was acting ‘autistic’ when they were upset, angry or being stupid."

I became aware that my experiences were, in some ways, very different from those of my neurotypical peers. While many of them spoke about their increasing anxiety and mood swings, I felt I experienced these symptoms more acutely. My anxiety had increased, particularly around socialising and university, to the point where I was having panic attacks on an almost daily basis.

Most neurotypical people will not understand how it feels as an autistic person, masking every day to appear ‘normal’ and never truly knowing if you are doing a good enough job. Some days I thought I was doing okay, and no one could even tell I was autistic, which was my ultimate goal. Other days, I felt people thought I was aloof, cold, weird. On Rigevidon, these days became more frequent.

Critical thinking about my contraceptive

Although my experiences of Rigevidon felt different from my friends’ experiences, something we could all relate to was the casual sexism we encountered if we expressed certain ‘undesirable’ emotions. Most women I know have experienced this kind of sexism, such as being asked, “Are you on your period?” and other medical and menstrual slights when they express anger, frustration or agitation.

As an autistic woman I have yet another layer of stereotyping to contend with. When people are aware of my diagnosis, I must fight to prove my emotions are valid, and not a product of being an ‘Aspie’ having a meltdown.

Then I discovered feminism. For me, it represented a complete change of mindset. I began to see that concepts and structures I had assumed were neutral were, in fact, helping to maintain societal inequalities.

He only saw my diagnosis rather than the woman sitting in front of him, who simply wanted to change contraceptive.

I had blindly taken Rigevidon because a doctor told me to, someone I thought always knew best and had my best interests at heart. Feminism made me a critical thinker about female contraception and women’s experiences of healthcare. I saw that our realities are often questioned, debated and even refuted by some medical professionals, especially concerning contraception. Frequently, we are met with half-sympathetic nods and sent on our way.

"I had blindly taken Rigevidon because a doctor told me to, someone I thought always knew best and had my best interests at heart."

When I eventually went to a doctor to change contraceptives, I was asked about my academic performance at university. Since I was still academically achieving, my male doctor did not see a need to change contraceptives. When I pushed back, explaining that I was feeling paranoia and increased anxiety in social situations, he told me about a helpline I could call.

The doctor then glanced at my medical records. He saw that I’d had help understanding emotions and socialising when I was younger, and suggested I consider seeking counselling as an adult for my “difficulties”. Although I understand why he suggested this, it made me feel that he only saw my diagnosis rather than the woman sitting in front of him, who simply wanted to change contraceptive. I left his office still on Rigevidon.

A group of unseen women

The 2020 docu-series ‘Sex, Explained’ explores different aspects of sex, including the history of contraception. One episode, ‘Birth Control’, investigates women’s adverse experiences with contraception, and explores the idea of a contraceptive pill for men.

I was shocked at the mention of a male contraceptive pill. I had never been aware of attempts to develop one. This made me think deeper about feminism and medicine, shaping my research throughout my master’s degree in Applied Gender Studies (Research Methods).

During my studies I found that neurodivergent women on contraception, like myself, were unseen and invisible. Are there other neurodivergent women like me who feel contraception makes their social anxiety worse? Are there others like me who feel their ability to mask slip away because of the pill? Are there others like me who feel medicine sees the diagnosis before the individual?

Finding myself after Rigevidon

Writing this in 2022, I am no longer on Rigevidon. For years I was blocked from changing my contraceptive. It was only when I managed to speak to a female doctor that my concerns were listened to, and action was taken to help me. She listened to what I had to say and didn’t question my experiences, using my words to shape her decision-making.

This was huge for me, and I imagine it would be for many other women too, especially neurodivergent women like me. When a doctor values our experiences and uses them to formulate decisions and prognoses, it has a major impact.

I am still figuring out what contraceptive is right for me, but I know that, for the first time in a while, I feel calm. I was on Rigevidon for seven formative years of my life. Had it been hijacking my ability to self-regulate, and intensifying the difficulties I already experience with autism?

"I am still figuring out what contraceptive is right for me, but I know that, for the first time in a while, I feel calm."

Now I’m free of Rigevidon, I believe I’m truly myself. Although I still struggle with the same problems, and my autism is still there, affecting my thoughts and behaviours, I am better able to regulate my emotions and cope in a variety of situations and stresses. I have been panic-attack-free for seven months now, the longest stretch of time since I had my first panic attack at 15 years old.

I used to believe panic attacks were an intrinsic part of me and my inability to cope, a clear symptom of my autism getting the better of me. Now this belief is beginning to change. Although I cannot be sure, I think Rigevidon was a primary factor in causing my panic attacks. It’s hard to be certain, because voices like mine are rarely heard.

I hope sharing my story can help another autistic or neurodivergent woman feel seen. And, even if you haven’t had experiences like mine, I hope you can see that I’m not an anomaly, even if I am treated like one.

About the contributors

Catriona Reid

Catriona is a researcher and community development worker, currently working in the Rape Crisis Network. Having just completed an MSc in Applied Gender Studies (Research Methods), Catriona hopes to continue research within feminist science and technology studies, particularly around sexual health and contraception, and in causes and prevention of gender-based violence. Her previous writing on the male contraceptive pill has been published on the Postgraduate Gender Research Network of Scotland.

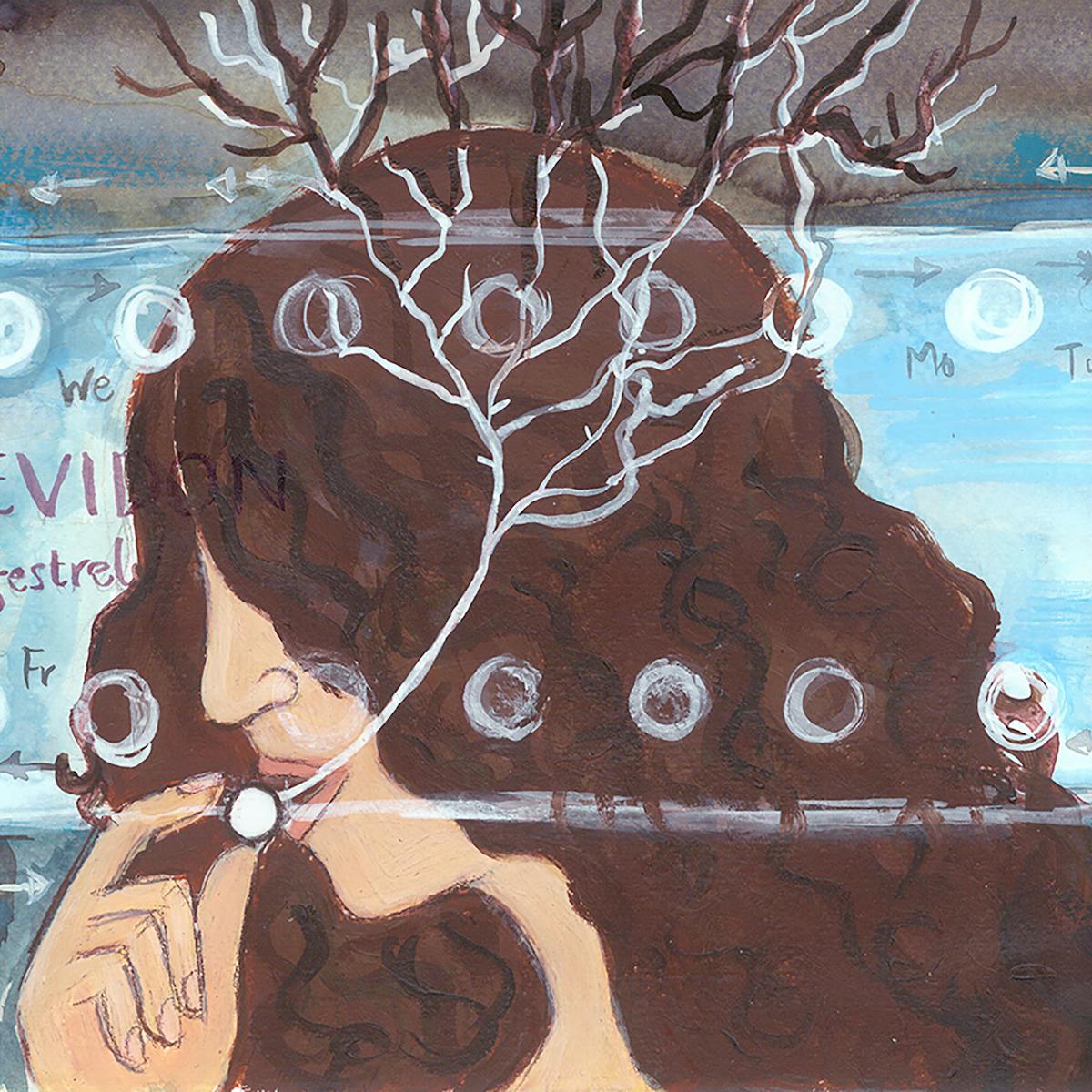

Natasha Almeida

Natasha Almeida is an illustrator and printmaker based in Newport South Wales who makes lino prints as well as ink and mixed-media pieces. She gets a lot of inspiration from exploring and connecting with the natural world. Portraiture, wildlife and plant life are recurring themes.