The plant lore around the mandrake goes back to ancient times. Kate Quarry and Lalita Kaplish root around for what has made this unremarkable-looking plant so magical.

Mandrake medicine and myths

Words by Kate Quarrywords by Lalita Kaplish

- In pictures

The mandrake is a perennial herb with a large root, purple flowers and poisonous yellow fruit. It is native to the Mediterranean region and was familiar to the Romans, Greeks and Middle Eastern cultures. It has a long history of medicinal use, and one of the oldest and most common uses was as a fertility aid. In Genesis, the first book of the Old Testament, Jacob’s wives, the sisters Leah and Rachel, compete to provide him with children with the help of mandrake.

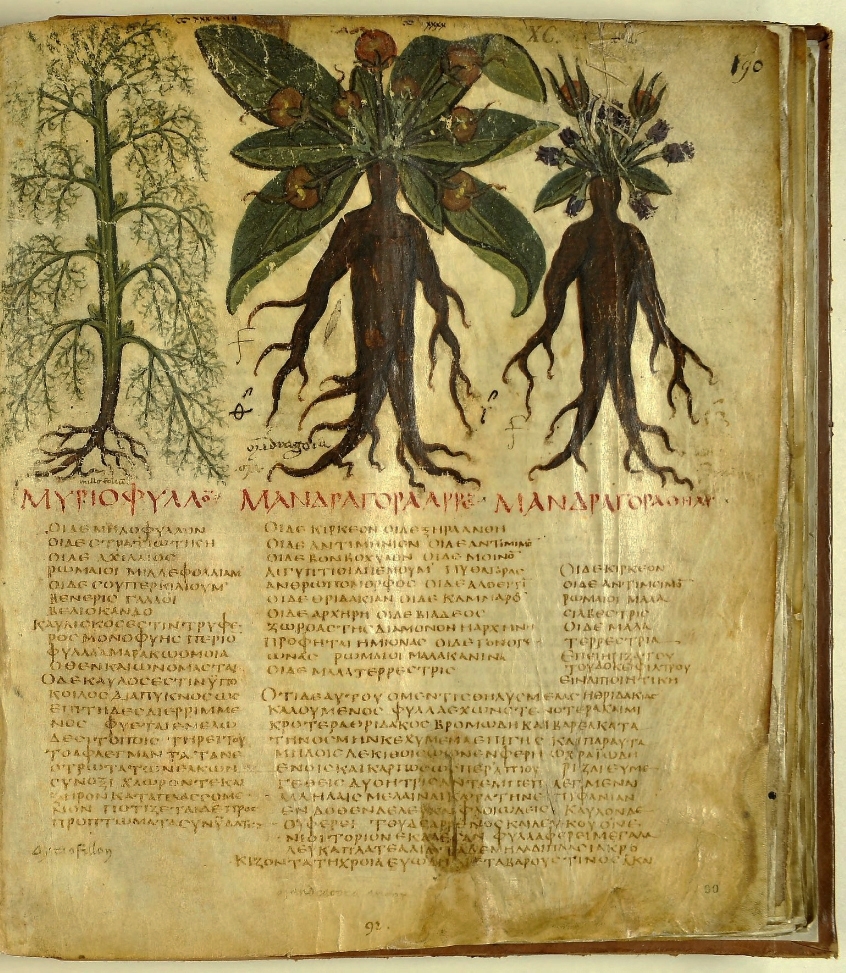

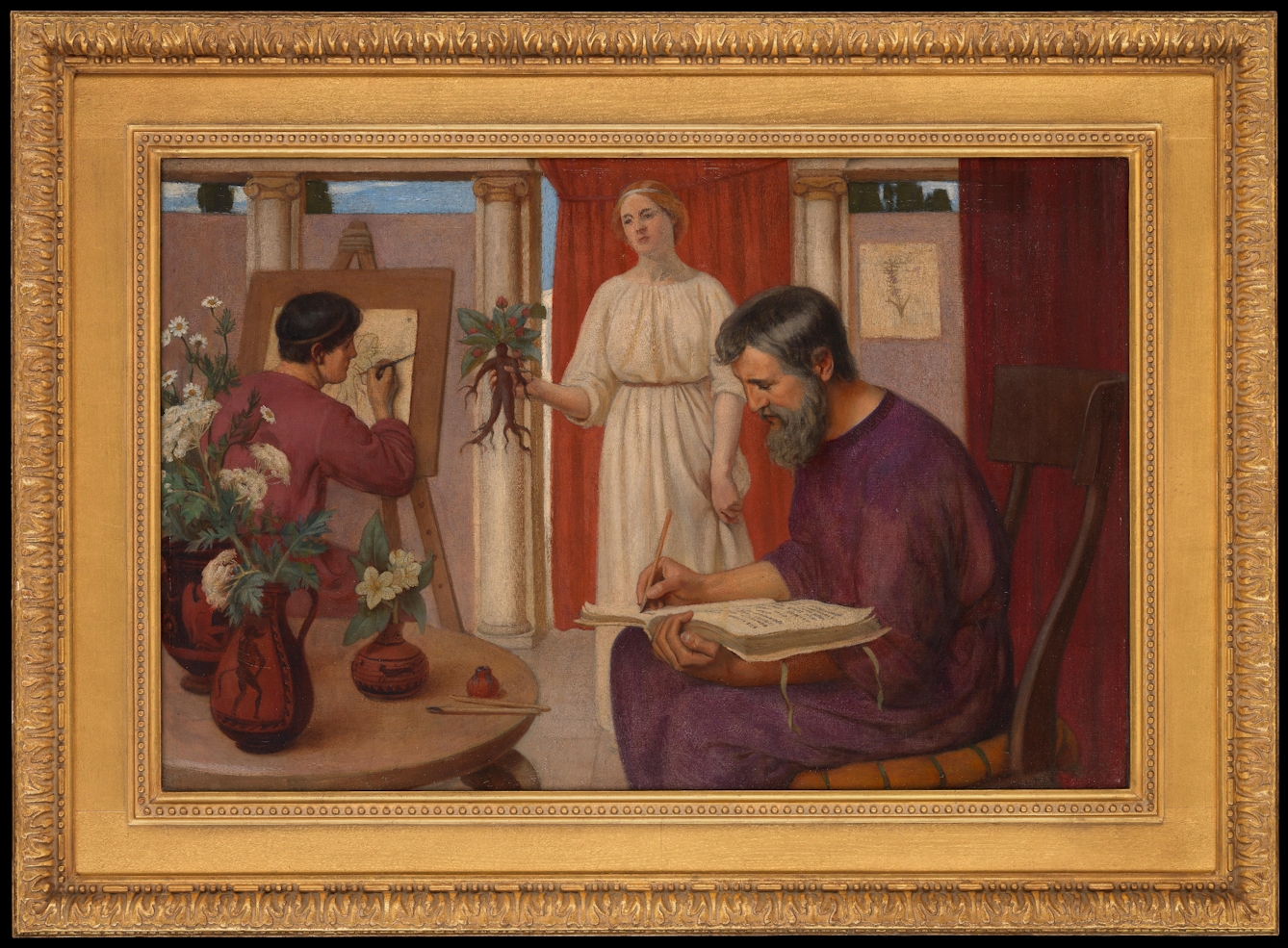

In the first century CE, the Ancient Greek physician and botanist Pedanius Dioscorides noted the human-like form of the mandrake’s roots and indicated its use as an anaesthetic for surgical procedures such as amputation. His comprehensive medical treatise, ‘De materia medica’, was widely copied, circulated in the original Greek, and later translated and modified in Latin and Arabic for many centuries. The Romans generally mixed mandrake with wine and other herbs as a sedative or sleeping draught.

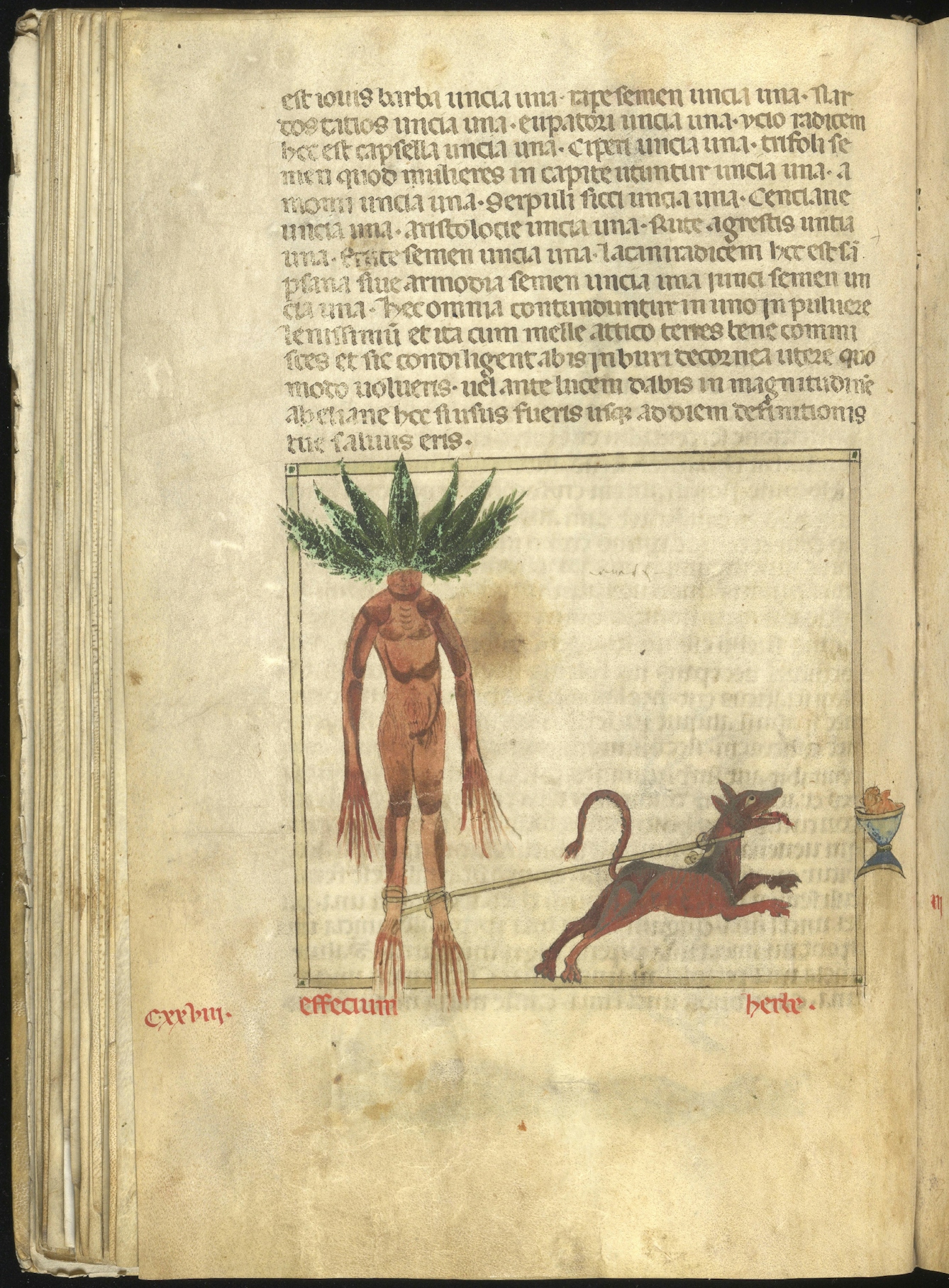

Perhaps because of its hallucinogenic and toxic properties, the mandrake was also associated with magical and supernatural powers. The plant was said to emit a cry so powerful that it could kill the person who tried to uproot it, a myth that was perpetuated in medieval herbals, which advised plant-gatherers to attach the plant to a hungry dog who was then allowed to run towards a dish of food, thus uprooting the plant as it ran. The dog might die, but the herbalist would be safe if they kept their distance and blocked their ears. The same story made an appearance in the Harry Potter books and films, where the young wizards were trained to wear ear protectors when transplanting mandrakes.

The mandrake was connected with witchcraft as well, perhaps because of its use by female midwives and healers for fertility and childbirth. Jeanne d’Arc (d. 1431), for example, was accused at her trial of carrying a mandrake root as evidence of her witchcraft. Another myth was that mandrake plants could be found at the foot of gallows, where the semen of hanged men had fallen. It was said that witches would gather these plants to impregnate themselves. This idea inspired the 1911 German novel ‘Alraune’ (named after the German for an amulet made from mandrake root), in which a scientist uses the semen of a hanged murderer to artificially inseminate a sex worker. The resulting child, Alraune, grows up to have no concept of love and engages in “sexual perversions”.

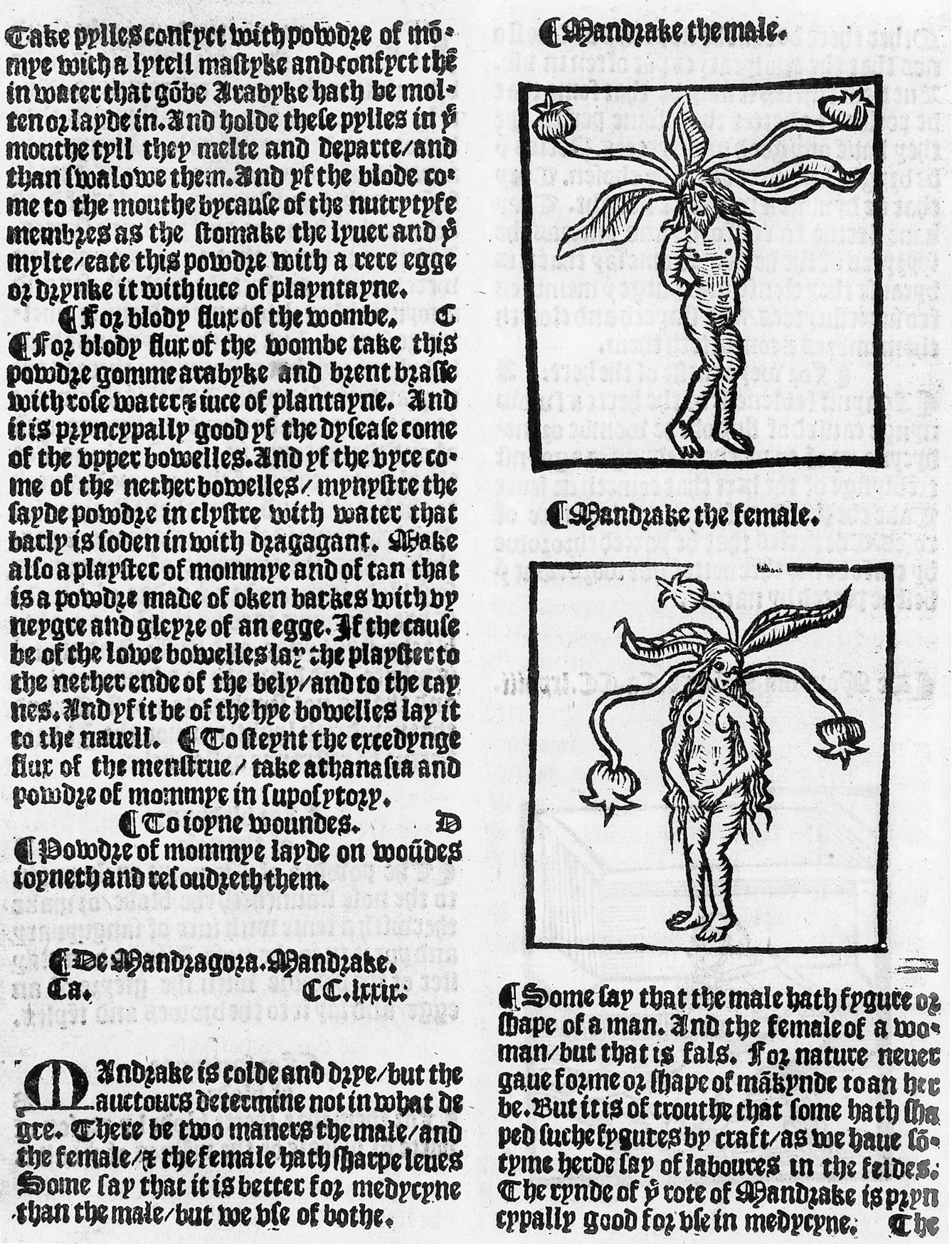

According to the 15th-century doctrine of signatures, the medicinal use of a plant was indicated by how closely some part of it resembled a human body part or organ. The fact that the mandrake root resembled an entire human body was a sign of its potency, and this connection to the human form as a whole may have been why it was associated with fertility. Some herbals showed ‘male’ and ‘female’ versions of the root, which could be used to strengthen male or female fertility.

The power of the mandrake extended beyond ingesting it: to use it as a fertility aid, the root could be placed under a person’s pillow, or it could be kept close to someone ill to treat their condition. In the film ‘Pan’s Labyrinth’, for example, the heroine places the root in a saucer of milk under her sick mother’s bed. Roots were sometimes carved to enhance their human form and could be carried on the person as a charm or talisman, not only to help with conception, but to help find love and bring good fortune.

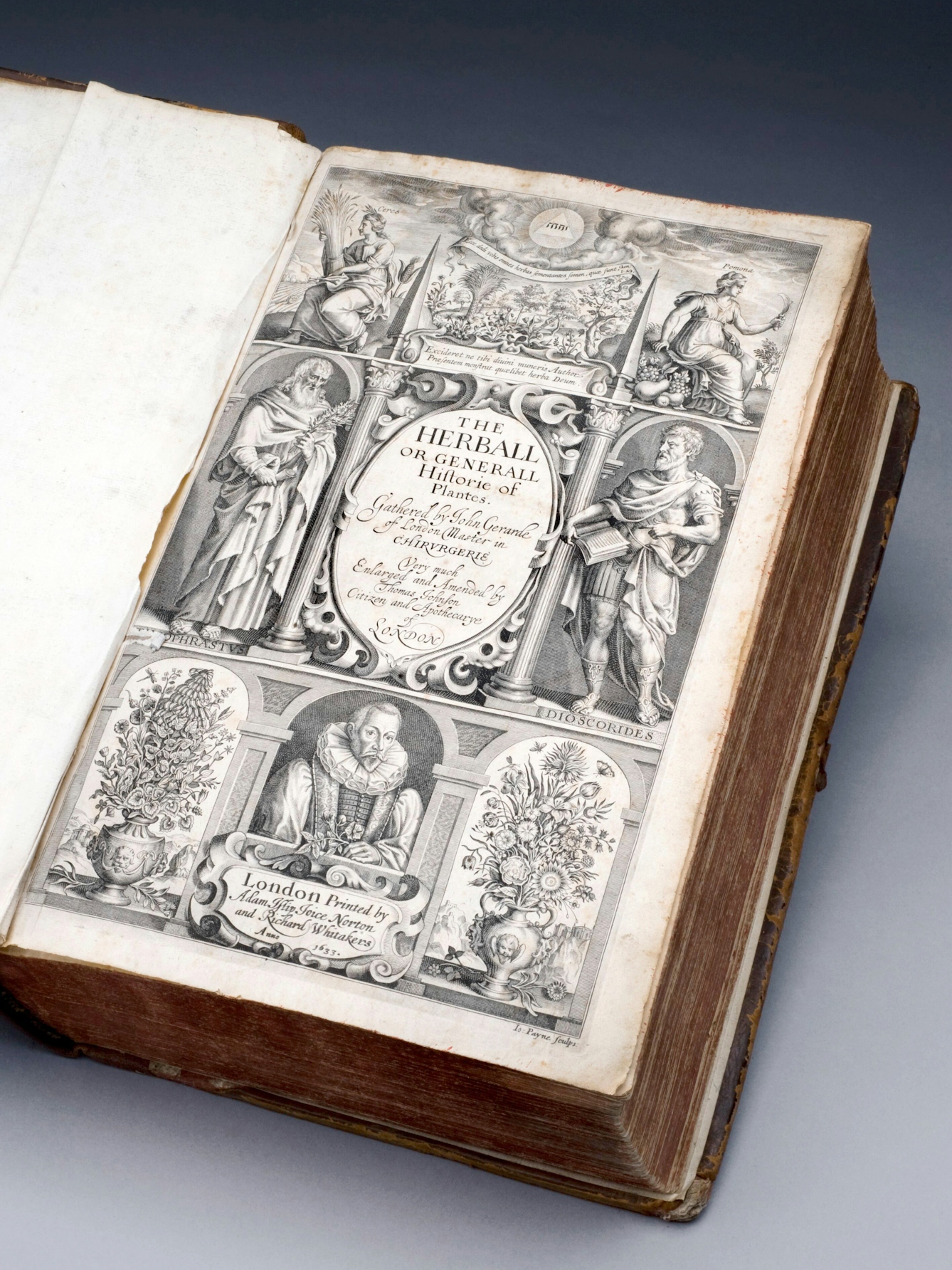

As a Mediterranean native, the plant was less common in damp, cool Britain, and there was a ready market for fake mandrakes made out of bryony root (also known as false mandrake). One reason for the myth of the mandrake’s shriek may have been to deter people trying to steal hard-to-come-by mandrake plants. By the 17th century, however, the power of the mandrake had begun to wane. John Gerard’s‘ ‘Herball’ complained that “there have been many ridiculous tales brought up of this plant, whether of old wives or runnegate surgeons or phisick mongers, I know not”.

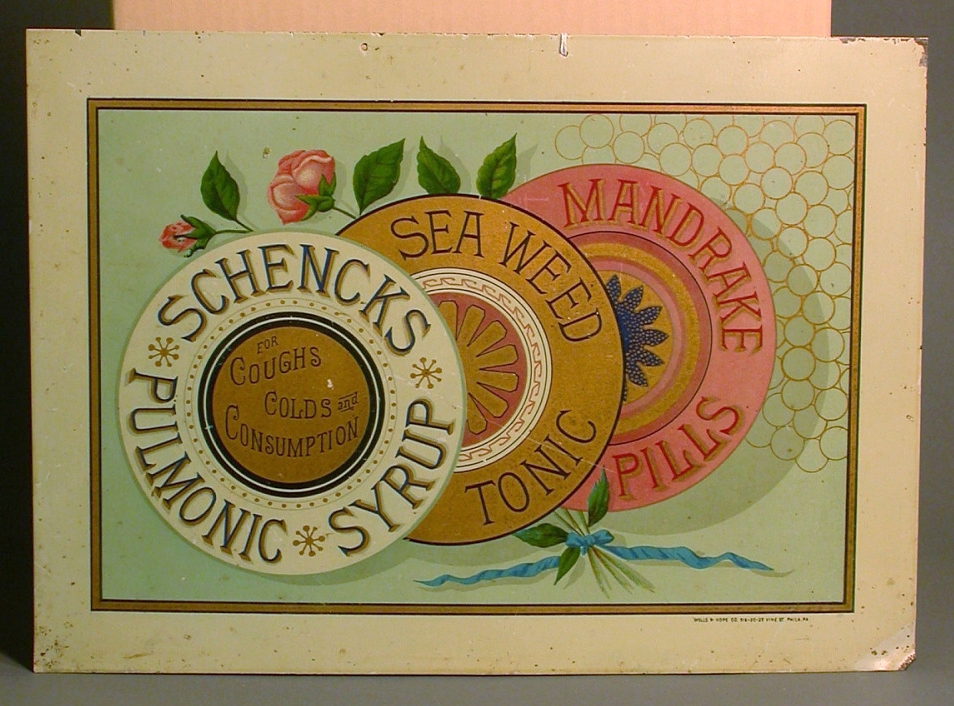

Mandrakes could still be found in patent medicines in the 19th century. In 1887 Dr Schenck published a 36-page pamphlet extolling the virtues of his mandrake pills, which he claims are “the rational way of treating all diseases”. He explains that the “cathartic, emetic” actions of mandrake will treat “disturbed conditions of stomach, liver, spleen, kidneys, bowels and blood”.

In 1889, the active chemical in the mandrake plant was isolated and identified as mandragorine, later confirmed as a mix of alkaloids. The alkaloids are a family of potent chemicals, still widely used in pharmaceuticals and responsible for the hallucinogenic and sedative (and toxic) effects of many other plants, including deadly nightshade. Once chemists could create these substances in the laboratory, they no longer needed to identify plants or prepare drugs from source, and plant lore became redundant. Stripped of the enchanting imagery and mythology found in herbals, references to the mandrake in 19th-century pharmacopoeias were sadly diminished. The mandrake may have become just another botanical specimen, but its mystic past still holds an intoxicating allure.

About the authors

Kate Quarry

Kate Quarry is a freelance subeditor working with Wellcome Collection’s Digital Editorial team.

Lalita Kaplish

Lalita is a digital content editor at Wellcome Collection with particular interests in the history of science and medicine and discovering hidden stories in our collections.