Fifty years ago, experiments exploring the effects on mice of high-density living environments were seen as predictions for human behaviour in similar circumstances. In short, the results were not positive. But perhaps compassionate kinship, one of the ways current thinking proposes to deflect the horror the rodents experienced, could save us.

It’s getting mighty crowded

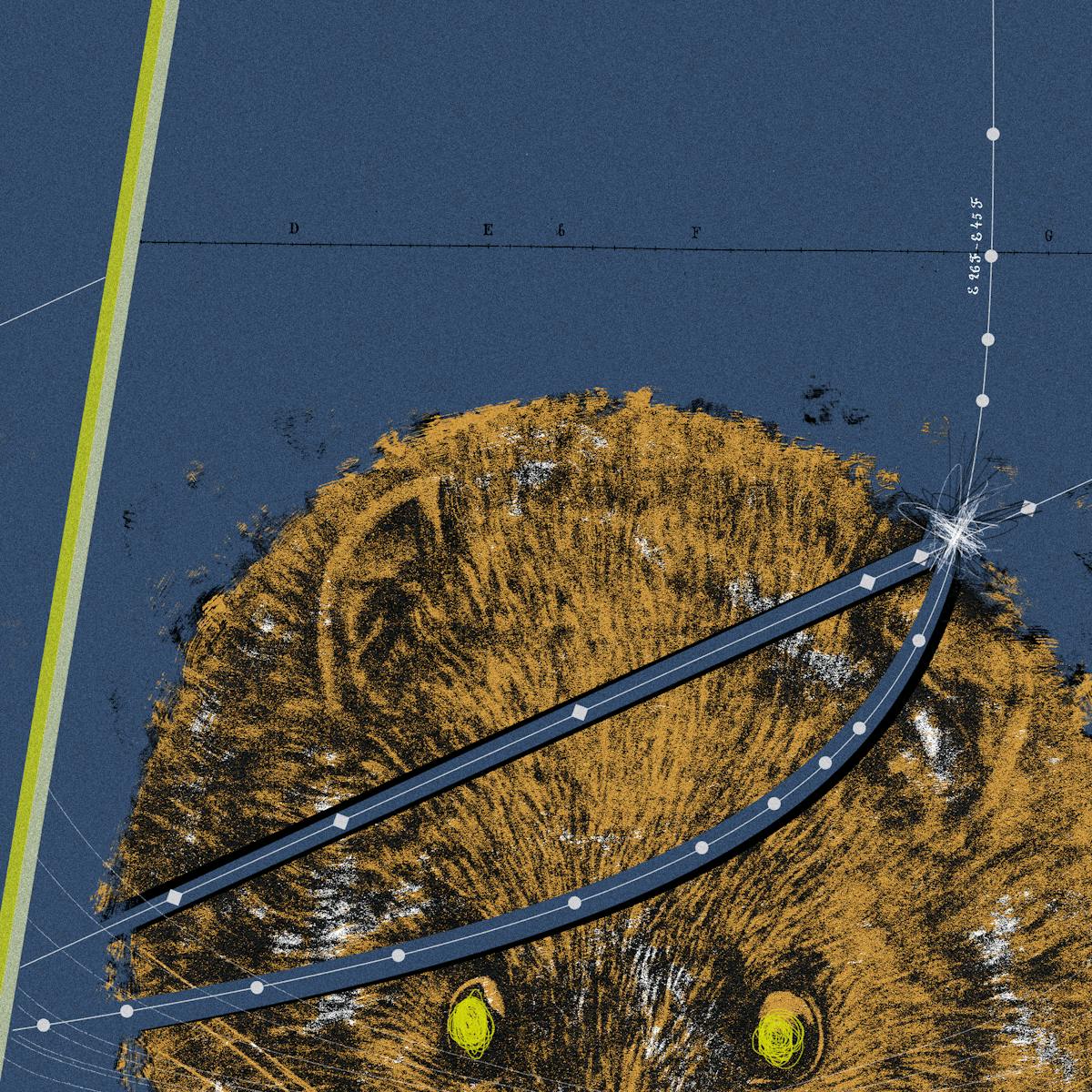

Words by Charlotte Sleighartwork by Gergo Vargaaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

Between 1968 and 1972, the American National Institute of Mental Health carried out a series of experiments on the results of high-density living, with horrifying results. Reproductive abnormality, parental neglect, violence and even cannibalism were triggered.

These, thankfully, were not human experiments. They were conducted on mice, penned into an enclosure 2.7m square, with space to climb and hide. The mice were given all the food and water they required, kept clean and free from disease, and left to reproduce unchecked. Such benign starting conditions were all it took for the horror to unfold.

The scientist in charge of this furry dystopia was John B Calhoun, and he explicitly linked his research with the biblical apocalypse. By providing the mice with ideal living conditions, he wrote, he had ‘defeated’ for them the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse described in the Book of Revelation. These four – which Calhoun interpreted as being sword, famine, pestilence and wild beasts – could be understood as the normal environmental pressures of disease and predation.

In killing these ‘horsemen’, however, Calhoun had removed the impetus for survival and evolution. Relieved of the need to find food or avoid predators, the mice had committed race suicide. Thus Calhoun claimed to have decoded the mysterious meaning of Revelation, discovering something that he called “the death of the second death”.

Morals and mass starvation

Eccentric though his conclusions were, Calhoun had been invited to develop his experiments by one of the United States’ most august institutions of human science: important human parallels were considered to be at stake.

For, since shortly after World War II, American attention had turned to the so-called “population bomb” and the dangerous possibility that the needs of the Earth’s rapidly growing population would outstrip its resources. Writers and scientists made drastic and well-publicised predictions about mass starvation as early as the 1970s.

The cluster of conferences and books on this theme echoed warnings first set out at the end of the 18th century. The Reverend Thomas Malthus, though he lived in the genteel world described by Jane Austen, always saw nature out of the corner of his eye, clawing at its edges.

“Malthus argued that human expansion would always reach limits defined by nature: want and famine, and with these, the human inclination to conflict.”

In his ‘Essay on the Principle of Population(view in catalogue)’, first published in 1798, Malthus argued that human expansion would always reach limits defined by nature: want and famine, and with these, the human inclination to conflict. There was no point in extending relief to the poor, said Malthus – they would only produce more children until the problem of hunger returned, hydra-headed. Only moral control in limiting procreation could save them.

The main example that Malthus had in mind as he wrote was the process of colonisation underway in North America and Australia. He was sceptical about its advisability – even, perhaps, its morals. It seemed to him that these lands had reached natural carrying capacity with their indigenous populations, and that displacing these “savage” peoples in hopes of wealth and riches (and, in the case of the US, rational revolution) was an act that was in vain, as well as wicked.

Prejudice in population research

All this was the backdrop to Calhoun’s mouse investigations. In a series of films made to explain and promote his research, Calhoun was quick to explain their significance for the human population. Drawing a graph on a blackboard, he explained that the period for doubling of the Earth’s population had been halving since civilisation began.

By the 11th period of doubling – the early 21st century – the human population would max out with death and destruction. He gave humanity 15 years to decide how it was going to respond to this challenge. The mice showed how not to do it.

Calhoun was actually not that bothered by the violence of the mice. What preoccupied him more was the problem of what he called “the beautiful ones”, males that groomed themselves endlessly and declined to fight or mate.

Calhoun’s distaste for these individuals echoes conventional stereotyping of male homosexual characteristics in the period. Giving up the desire for heterosexual procreation might reduce pressure on food resources, but for Calhoun it would come at the cost of drives that were most properly human.

Extending his now offensive outlook on sexuality to matters of race, Calhoun also noted the danger of ‘tribalism’ in a stable population. The racialised element of Calhoun’s outlook was a well-established theme in population discourse.

“In killing these ‘horsemen’, Calhoun had removed the impetus for survival and evolution. Relieved of the need to find food or avoid predators, the mice had committed race suicide.”

Referring to ‘overpopulation’ was often a way for white people to express their fear of growing numbers of non-white people, whether ‘displacing’ them in their neighbourhoods or consuming the resources of the world. Magazines that described Calhoun’s experiments as replicating ‘urban’ conditions were dog-whistle references to Black America.

But there is a wicked trap in ceasing scientific discussion about world population on account of its racist history. By doing so, we may fall into the arms of the capitalist fundamentalists who wish to deny all limits to growth upon the planet. More people, more profit – ad infinitum! Malthus’s fundamental point is correct: there is a carrying capacity to the Earth, a limit to the resources available to support a species, calculated as about half of what we are presently consuming.

Malthus was also correct in observing that the displacement of indigenous populations by high-consuming settlers was the main factor in this process. High-consuming citizens of the Global North are disproportionately responsible for the planetary strain compared to those of the Global South.

Ways to subvert selfishness

One inspiring solution comes from those who aspire to “make kin, not babies”. This principle, coined by philosopher Donna Haraway, gets at the idea that our best option, both practically and spiritually, is to extend and expand our compassion and nurture to humans other than our most immediate genetic relatives.

Faced with the environmental apocalypse, many people are not just deciding “not to have children”, but actively choosing to participate in raising nieces, nephews and children in their social circle. It is a ‘queering’ of parenthood that, far from being a pathology as Calhoun feared, turns out to be good for us all.

Millions of people are already being forced to seek new homes due to climatic degradation, and this number will only grow in the coming years. The best outcome for all will entail inhabitants of rich countries figuring out how to find kinship with the children – and adults – who arrive for this reason.

People who work in creative, media and educational settings all have the opportunity to help current inhabitants of the Global North to hear the stories of new arrivals; to expand and celebrate who counts as ‘us’. ‘The Great Global Bake Off’, anyone? ‘Climate Come Dancing’?

Calhoun proclaimed that excess population might cause the death of “humanity as we know it”. But if humanity can morph from procreative selfishness to kinship intentionally and compassionately bestowed, that might just be a good thing.

About the contributors

Charlotte Sleigh

Charlotte Sleigh is an interdisciplinary writer and practitioner in the science humanities. Her most recent book is ‘Human’ (Reaktion, 2020). She is Honorary Professor at the Department of Science and Technology Studies, UCL, and current president of the British Society for the History of Science.

Gergo Varga

Gergo Varga is an illustrator, collage animator, motion designer and the name behind ‘varrgo’. varrgo is a place where Gergo creates and animates mixed-media projects, particularly in the style of collages and cut-outs. He enjoys working with things that have already had a life, from old magazines to scribbles in a notebook. His longest-running creative project is ‘oners’, where he visualises one-minute quotes from contemporary thinkers. Gergo created the animations and illustrations for ‘Apocalypse How?’ and ‘Eugenics and Other Stories’, published on Wellcome Collection Stories.