When she was ill, Naomi Morris assumed she was on a straightforward journey from sickness to health. That’s what all the personal essays and celebrity memoirs about recovery promised. But what if our experiences of mental distress and ill health aren’t that neat? Naomi describes the pressure ill people feel to recover, and stay recovered, and why survival itself is success.

When my ill health coincided with the proliferation of the “personal essay” online, I assumed that my illnesses would eventually turn into a legible narrative – something I could, essentially, sell. I believed they would be worth something (culturally and monetarily); that turning them into a story would in some way eradicate any and all residual pain of having lived an interrupted life.

Mainstream depictions of ill health are often linear, focusing on an individual fight or battle with illness that is to be overcome. The climax is health, again. I wanted my own story to be regarded this way – for the hardship to mean something – and for a while, it did resemble the narrative of battling sickness to return to health.

After experiencing a prolonged period of chronic fatigue and debilitating anxiety when I was a teenager, I recovered enough to return to education. I went to university despite doubts over whether it would be possible for me to have ‘normal’ experiences. I held fast to this achievement. It was interpreted as proof that I was incredibly resilient and ultimately strong.

The spurious ‘achievement’ of health regained

Health has often been perceived to be a private matter and ill health something to disguise. The personal essay has established a type of confessional writing that is seemingly a natural partner for illness narratives, one in which disclosure is not only accepted but encouraged. The main crux of this personal writing is exposure of the intimate. Its radical nucleus is to be a liberating force by emphasising agency and ownership of our experience.

Julian the cat, named after Julian of Norwich, also known as Juliana of Norwich, who wrote Revelations of Divine Love, the earliest surviving book in England known to have been written by a woman.

However, a side effect of these types of stories becoming popular is their subsequent commodification. A slew of celebrities have expanded their repertoire to include mental health memoirs that are also accompanied by self-help interjections.

These books range from TV presenter Fearne Cotton’s ‘Calm: Working through life’s daily stresses to find a peaceful centre’ to political strategist Alastair Campbell’s ‘Living Better: How I learned to survive depression’. Meanwhile novelist Matt Haig’s ‘Reasons to Stay Alive’, an autobiographical account of his experience with unipolar depression, was in the UK top ten for 46 weeks, turning him into a celebrity author.

There is no doubt that Haig’s story, and others, have started conversations that otherwise might not have happened. The fact they’ve become bestsellers shows the appetite for stories that reflect the realities of illness and explore how hard it can be to stay alive.

These books implicitly suggest ill health should be something we can ultimately escape, fuelled by self-motivation, hope and resilience.

“Unrecovered does not mean the refusal to get well, but rather an active protest at the narrow confines of recovery.”

But these accounts remain within the bounds of acceptability. Through the pursuit of recovery, of self-adaptation, these books implicitly suggest ill health should be something we can ultimately escape, fuelled by self-motivation, hope and resilience. Illness should not be chronic.

They fit the genre of ‘The Recovery Narrative’ — a term used by Angela Woods, Akiko Hart and Helen Spandler to describe the increasing reliance on recovery as a “dominant approach to the management of mental distress and illness”.

Linear recovery narratives are not only endorsed through popular culture but, as Woods, Hart and Spandler write, a policy context in which patients are encouraged to “speak out” in accordance with preconceived “generic conventions”, such as a reaching “rock bottom” and getting better from there.

In ‘Recovering our Stories: A Small Act of Resistance’, Lucy Costa and Danielle Landry describe how “it is now commonplace for mental health organizations to solicit personal stories from clients – typically, about their fall into and subsequent recovery from mental illness”. Essentially, survivors and mental health patients are encouraged to tell their stories as a form of treatment. A decisive recovery is framed as a key component of the success story.

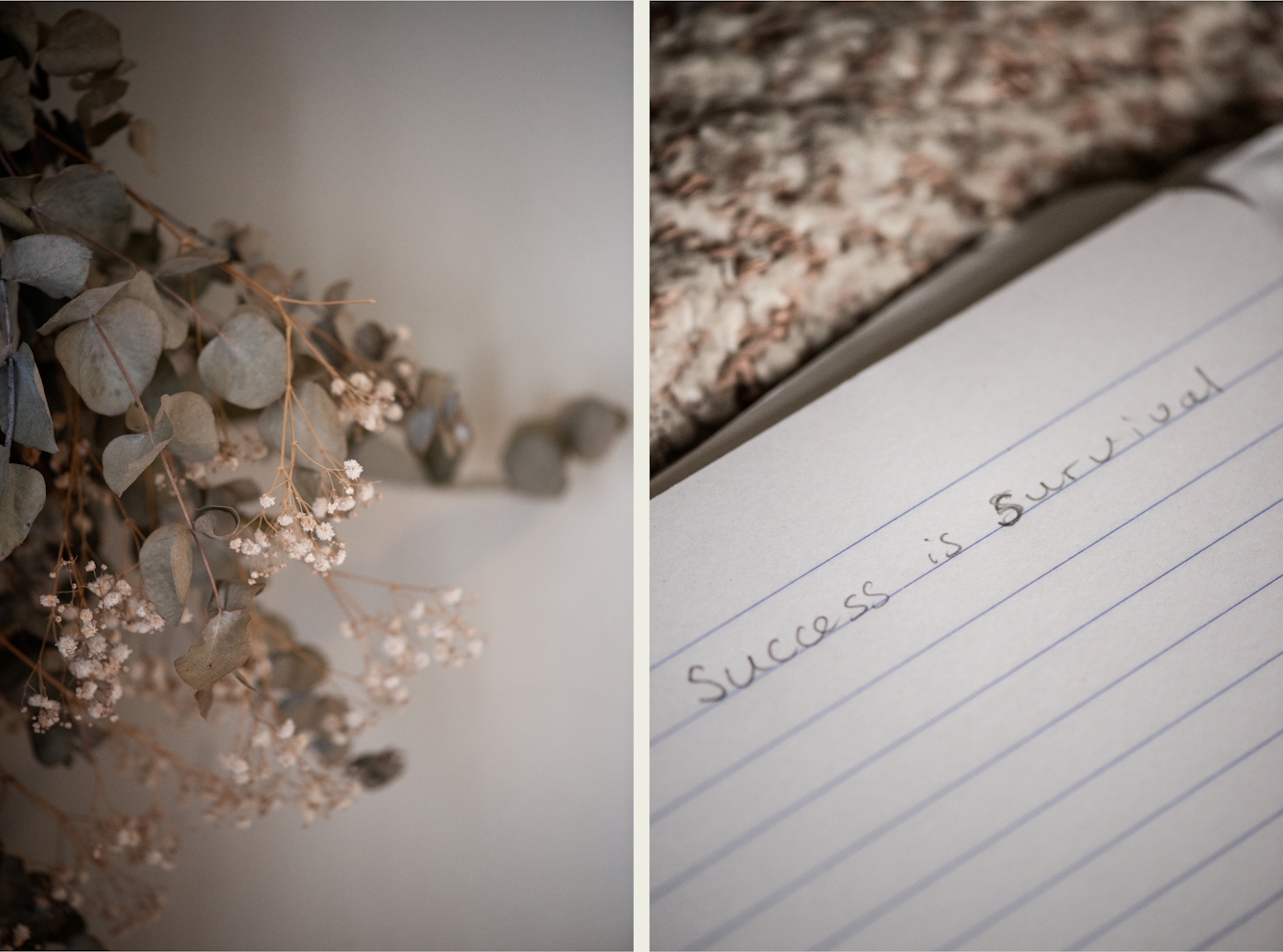

“When I was lost in the mire of illness, I pencilled “success is survival” on the end of my wooden bedframe, a quote attributed to Leonard Cohen.”

Unrecovered but surviving

When I was lost in the mire of illness, I pencilled “success is survival” on the end of my wooden bedframe, a quote attributed to Leonard Cohen. Recovery was something I strived for, but it felt completely out of my grasp. I was desperate for that narrative turn, the breakthrough: a straightforward journeying from sickness to health. I couldn’t really conceive of an alternative.

But not everyone can get well in the way endorsed by recovery narratives. By its very nature, chronic illness resists having a beginning, middle and end. To imagine that surviving was an accomplishment in itself was a great comfort.

The driving force of compulsory recovery needs this antithesis: alternative narratives that can speak to a wider array of experiences. For Recovery in the Bin, a user group for mental health survivors, this means advocating for the use of the term ‘unrecovered’ — a term, they say, “as valid and legitimate as ‘Recovered’”. Unrecovered does not mean the refusal to get well, but rather an active protest at the narrow confines of recovery.

“Not everyone can get well in the way endorsed by recovery narratives. By its very nature, chronic illness resists having a beginning, middle and end.”

By individualising our personal stories – our illness narratives – we fail to grapple with the contextual aspects of health and wellbeing. It is the world as it is that also contributes to our sickness. In Recovery in the Bin’s words, recovery is “impossible for many of us because of the intolerable social and economic conditions, such as poor housing, poverty, stigma, racism, sexism, unreasonable work expectations, and countless other barriers”.

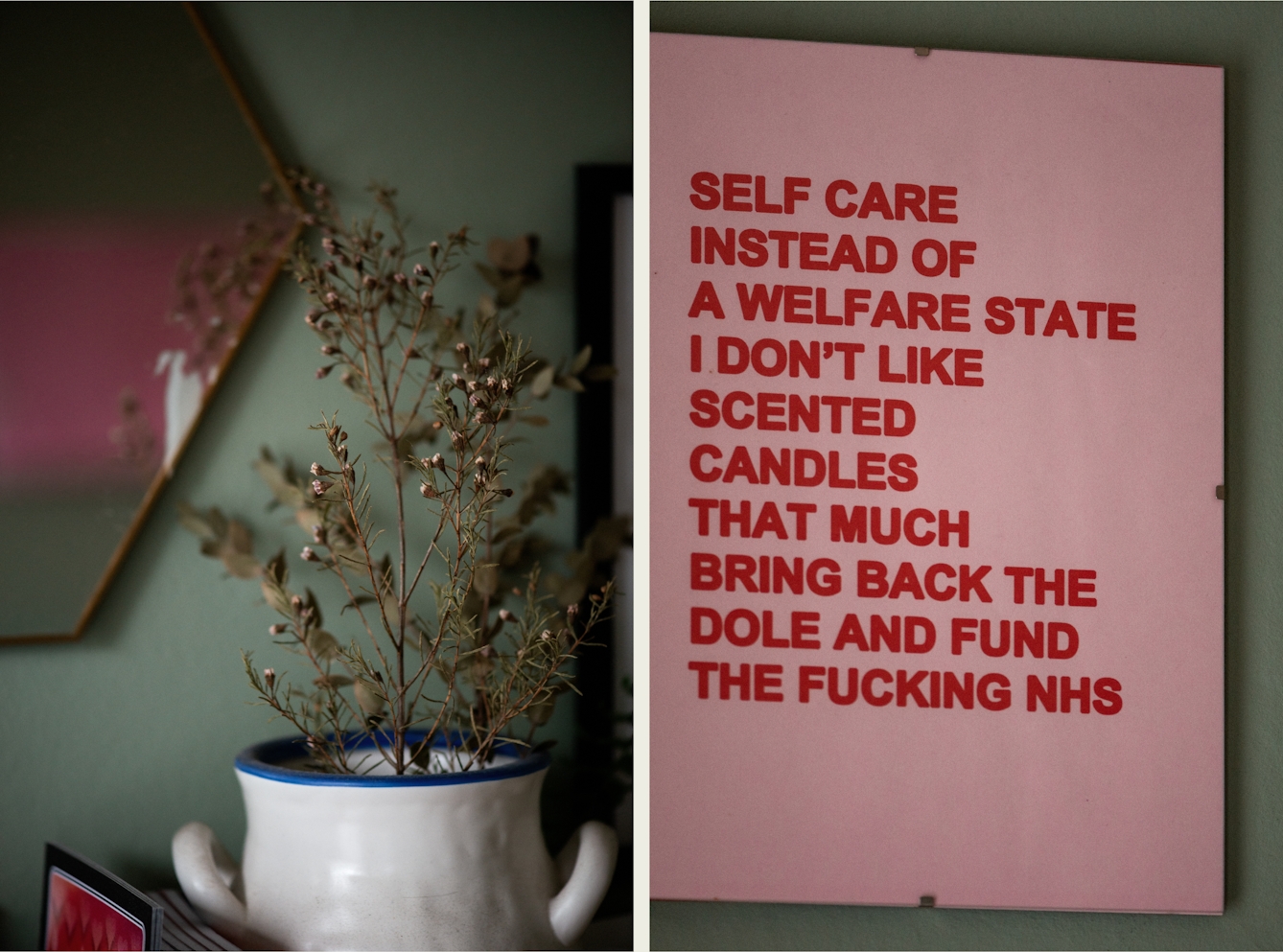

Recovery narratives often follow a case of singular fortitude, a battle to fight through our own will. In ‘The Bare Minimum Manifesto’, the Bare Minimum Collective rail against this “neoliberal requirement for self-improvement”, demanding instead that we reject all ideas of “linear progress”.

Rather, recovery narratives have the potential to be expanded: as Woods, Hart and Spandler conclude, “There is good reason to continue to tell, listen to and celebrate Recovery Narratives… there [is also] good reason to question whether… it may be considerably limiting what it is possible to see, hear, acknowledge or act upon.”

Sometimes our mental distress, our ill health, can’t be packaged into a story with a neat narrative arc. I’d experienced over a decade of undulating health before I realised my illnesses wouldn’t have the orderly conclusion I’d expected – that I wouldn’t write my story, sell it, and then heal.

About the contributors

Naomi Morris

Naomi Morris is a writer of non-fiction and poetry originally from Birmingham. Her work has been published in The New Statesman, Dazed, Polyester, Gutter, and Ache. She was an original diarist for Rookie Magazine. Naomi’s first pamphlet of poems, ‘Earth Sign’, won the 2018 Hollingworth Prize and was published by Partus and Sine Wave Peak in 2019. Her most recent collection ‘Hyperlove’, was published by Makina Books in September 2021. She lives in London with her cat, Julian.

Camilla Greenwell

Camilla Greenwell is a photographer specialising in dance, performance and portraiture. She regularly works with Sadler’s Wells, Barbican, Candoco, Rambert, The Place, the Guardian, the British Red Cross, Art on the Underground and Wellcome Collection.