There are currently tens of thousands of asylum seekers, refugees and other displaced people in Greece, with many trapped in insecure and cramped accommodation. But good housing can be transformative, especially for those experiencing mental ill health. Writer George Kafka reports on two Athens-based projects that are helping displaced people by taking a housing-first approach.

Via an interpreter, Mamadou tells me, “I have a very long story to share.” We settle on a shady bench in the Pedion Tou Areos park in central Athens. He takes short breaks during our conversation: it’s not an easy story to tell. “Since I’ve had counselling and spoken to good people, I feel stronger and more able to talk about it.”

Mamadou and his brother Abdoulaye are victims of torture and political persecution in their home country of Guinea. After escaping state authorities, they fled the west African country in 2018. On their way to Greece they suffered extreme police brutality and medical neglect in Iran and Turkey before arriving on the island of Samos.

After eight months in isolated refugee camps, they eventually made it to Athens in July 2019. Here their situation continued to be precarious. “We were staying with eight or nine other people in just one room. The landlord would come and scream at us, tell us to leave and sometimes we'd have to sleep on the staircase or on the steps outside,” he explains. “We used to sleep sometimes at the bottom of the park here.”

Before they were forced to leave Guinea, life was very different. After graduating from university with a degree in geography, Mamadou had set up a business working as a photographer and a cameraman. Abdoulaye, meanwhile, worked as a hairdresser and had his own shop. “When we were in Guinea, we didn’t think we’d ever end up here,” Mamadou says. “If someone had told me I was going to end up here, I would have said, ‘No! I have everything.’ We had everything.”

Archaeological museum in the Exarcheia quarter of Athens (left) and the staircase to Mamadou’s apartment in Kypseli (right).

The inside of Mamadou’s apartment (left) and the Church of Saint Marina in Thissio, Athens (right).

The struggle for safe shelter

According to the UNHCR, there are currently over 170,000 refugees, asylum seekers and other displaced people in Greece. For those arriving in Athens, the options for safe and secure housing are limited. The Greek government and UNHCR provide some accommodation in camps disconnected from cities, or in more central apartments, although these are typically reserved for families and other groups of people who are considered vulnerable, are short-term, and only accessible via a highly complex bureaucratic maze.

For those who are not considered vulnerable, or those who are unable to navigate the system, overcrowded and unsafe private apartments or street homelessness are the only remaining options. That is, apart from the services being offered by a small handful of new housing organisations, such as Mazi and Chamomile.

Both organisations emerged in the last two years in direct response to the limitations and blind spots in the accommodation options for displaced people in the city. Mazi manages two houses in Athens, which are resident-run households for single men between the ages of 18 and 30. Chamomile works across 11 apartments, supporting people with mental health disorders.

Much more than four walls and a roof, both projects provide free housing with flexible tenancy periods. They take a holistic approach to their work, which ties secure housing to supporting the individual ambitions and aspirations of their residents, including Mamadou and Abdoulaye.

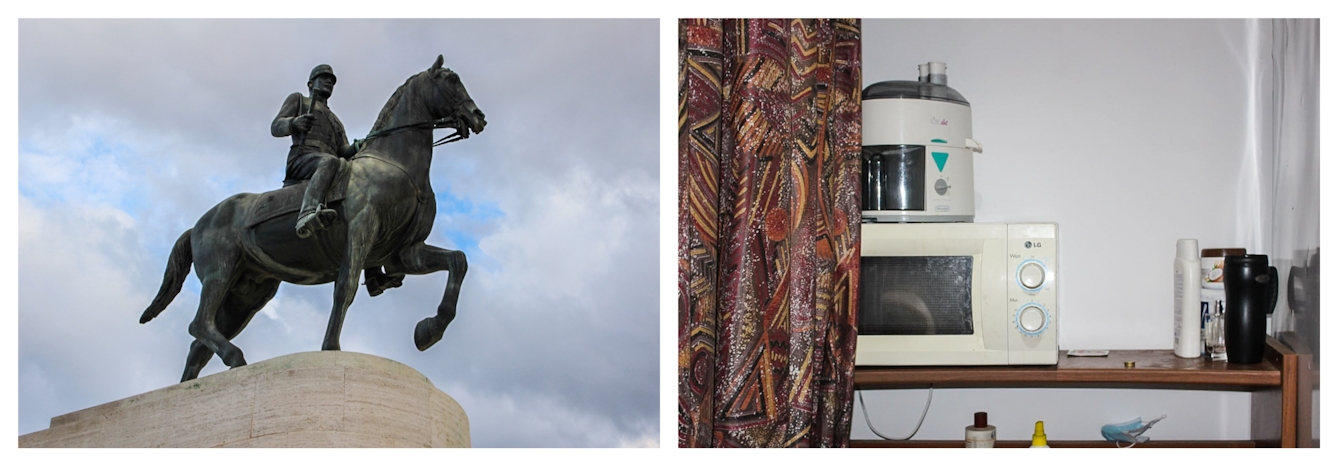

Statue of King Constantine I in the Pedion Areos park, Athens (left) and the microwave and food mixer in the corner of Mamadou’s apartment (right).

Entry door to Mamadou’s apartment in Kypseli, Athens (left) and a view of the Acropolis (right).

Fostering autonomy

“Differently from most housing provided by government organisations, we provide functional social support,” explains Sophia, a support worker for Mazi who manages a house of 11 young men in south Athens.

Sophia’s job includes working with the residents as a community and as individuals. She helps them with practical tasks – setting up a bank account or accessing legal support, for example – as well as broader social and emotional support that will allow residents to fulfil their ambitions beyond the house and, usually, beyond Greece.

Crucially, residents are able to stay in the Mazi house until they feel ready to move on. “Our approach is based on the understanding that this man is himself and he was always himself when he came to us,” explains Sophia. “This means that 99 per cent of our residents want to move on. They want to have their own place, their own space where they actually have independence and autonomy.”

Autonomy is also a crucial notion for Cassie Espinosa, co-founder of Chamomile. Chamomile provides financial and psychosocial support for people with a wide range of mental health challenges; some of which originated in their home countries, others that have developed as a result of the traumas of forced migration.

“What makes the project unique is that we don’t discriminate based on psychological challenges,” Cassie says. She explains that their integrated approach, supported by psychologists and psychiatrists, allows them to work with people who suffer from psychiatric disorders, individuals that other organisations might consider too risky.

“Why is it that we think that people as resilient as asylum seekers can’t also find a way to manage their lives with very clear framing provided by an organisation?” she asks. “We can have people with a wide range of disorders that really affect their lives, but everybody that's referred to us has a willingness to live autonomously.”

The kitchen cupboard in Mamadou’s apartment (left) and the ruins in the archeological site of the Acropolis (right).

Flowers on the landing in Mamadou’s apartment (left) and an avenue in the Pedion Areos park, Athens (right).

Rebuilding futures

After a year spent in unstable accommodation, Mamadou and Abdoulaye were put in touch with Chamomile. Today the brothers live in a one-bedroom apartment in Kypseli, close to the centre of Athens.

After moving into the apartment, Chamomile supported them in the asylum process (both have refugee status) and referred them to psychiatrists and psychologists via Medecins Sans Frontières. Mamadou was diagnosed with depression and post-traumatic stress disorder; when we met, he had recently finished a course for victims of torture.

He indicates the shorts he is wearing and the scars on his knee: “Before, I couldn't wear clothes like this because when I could see my scars, it would bring me back. Since my experiences with psychologists and psychiatrists, I can.”

When they gave us a house, we realised that life is still open and in front of us.

“Chamomile helped us because we were outside and lost in life,” he continues. “They took us and brought us close to them and they gave us a house. And when they gave us a house, we realised that life is still open and in front of us. It’s from that point onwards that we started having hope again.”

Now 28, Mamadou is thinking about the future. “I decided to think about what I was going to do with my life, and I want to be a care worker,” he says. “To work with elderly people and support them.”

Statue of Athena in the Pedion Aeros park (left) and a set of shelves in Mamadou’s apartment (right).

Housing and home

Although small in scale, Mazi and Chamomile are part of a broader global movement of residential projects with a “housing first” approach to social issues. First developed in New York in the early 1990s, this approach finds that a stable home provided without restrictions, alongside person-centred support, can be instrumental in overcoming cycles of homelessness, as well as other chronic health and social issues.

Currently most housing models for refugees and other displaced people across Europe are contingent on legal status and revolve around fixed periods that don’t reflect the needs or progress of an individual. They are often rule-based and restrict residents’ autonomy and agency.

These contrasting models might be described as the difference between housing as a physical place and home – an emotional place. We all know that to feel “at home” is to feel comfortable within four walls, but also comfortable within ourselves. Yet more than this, it’s a place from where our lives grow, our futures unfold.

For migrant and refugee populations, home is often a place forcibly left behind, sometimes without the possibility for return. Supported housing can’t bring those places back or make them safe. But projects like Mazi and Chamomile can provide the scaffolding to start constructing new futures and, maybe one day, a new place to feel at home.

Some names have been changed to protect privacy; with thanks to Maud Foxley for interpretation.

About the contributors

George Kafka

George Kafka is a London-born, Athens-based writer and editor. He writes about architecture, cities and contemporary culture for publications including BBC Culture, Frieze and The Architectural Review.

Mamadou

Mamadou (not his real name) is a victim of torture and political persecution in his home country of Guinea. After escaping state authorities, he fled the west African country in 2018. After eight months in isolated refugee camps, he eventually made it to Athens in July 2019. Before he was forced to leave Guinea, Mamadou graduated from university with a degree in geography and set up a business working as a photographer and a cameraman. In this set of images Mamadou documents his current living accommodation, set against the grandeur and historical monuments of his new home, Athens.