We think of assistive technology as something modern, and that people with mobility issues in the past were limited to their locality or confined within their homes. But there are clues in the manuscripts associated with medieval pilgrimage to suggest that disabled people could be highly mobile.

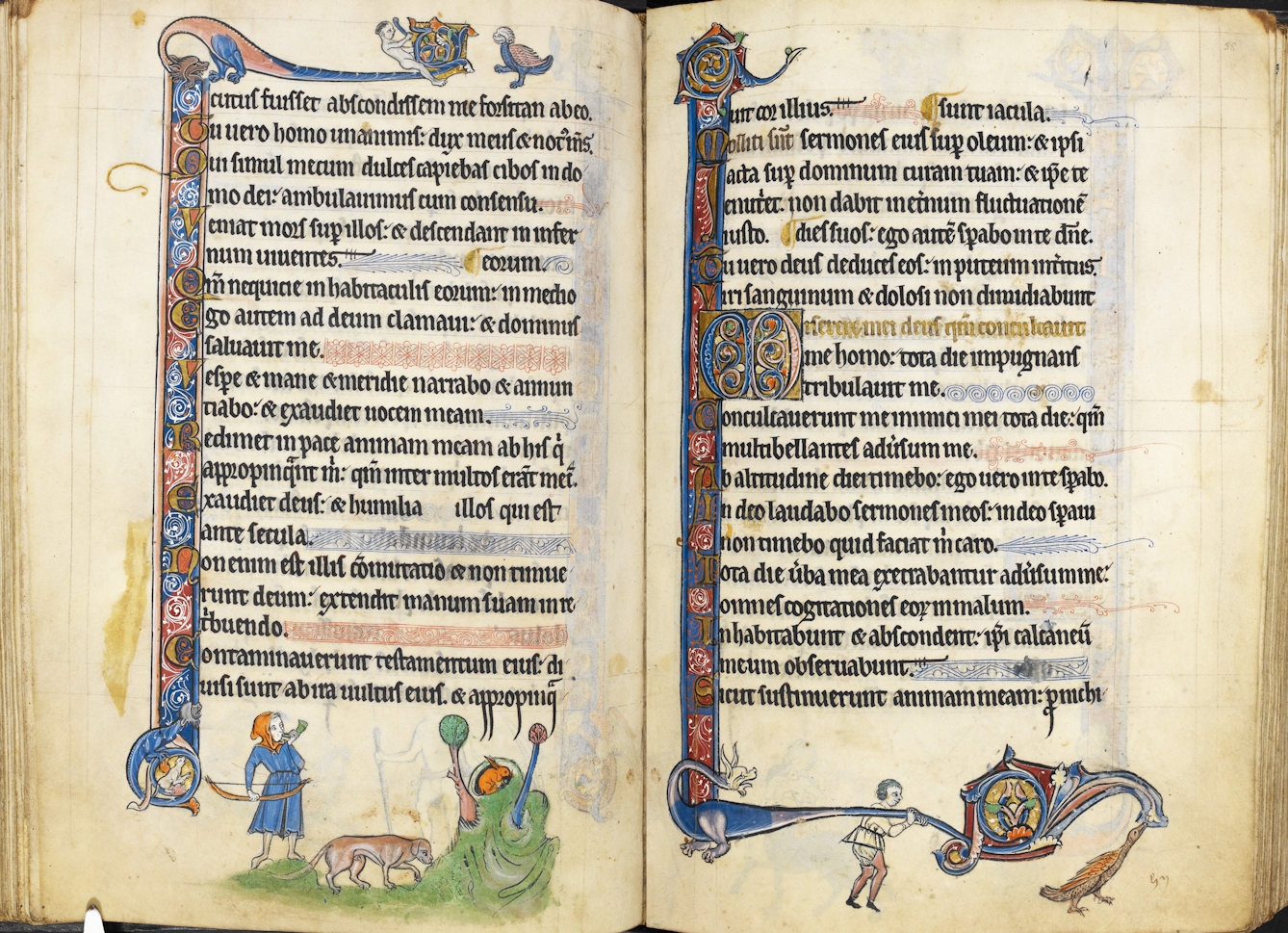

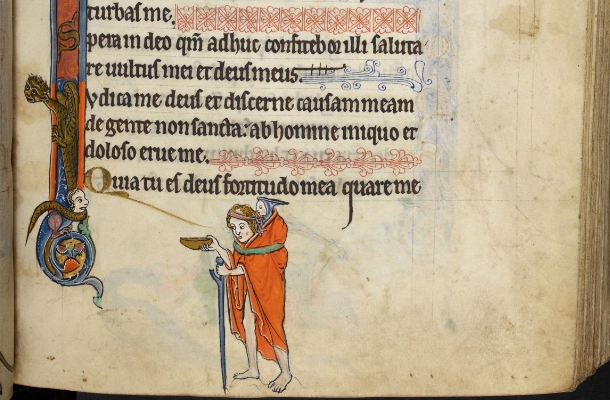

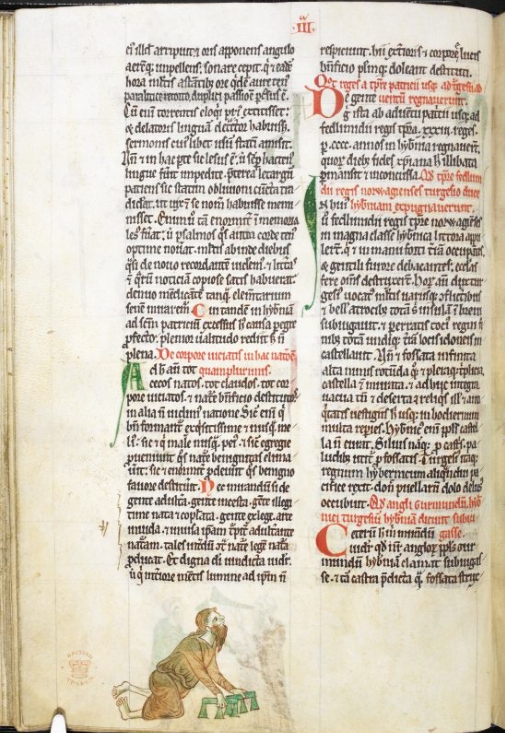

People visited religious shrines all over England and France, often travelling for days or weeks to reach their destination, using aids that were as familiar then as they are today. Written accounts of pilgrimage were sometimes accompanied by illustrations and doodles in the margins. Although these images are a rich source of evidence about medieval daily life, including individuals with disabilities, we have to be mindful that they are as much about entertainment as they are about recording events, and their primary function is to enrich the manuscript.

This illustration from an English psalm book (psalter) dated c. 1250 shows the most basic of mobility aids, a simple walking stick for support. The staff was a common aid in the Middle Ages, and widely used by travellers. In terms of the design, little has changed between these aids and a modern hiking staff. But the staff in this image is more likely to be a mobility aid than a simple trekking pole for two reasons: it is paired with individual’s lead foot in the same way such aids are still used and, secondly, the more common image of a walking staff is longer and has no distinct hand grip, as this one does.

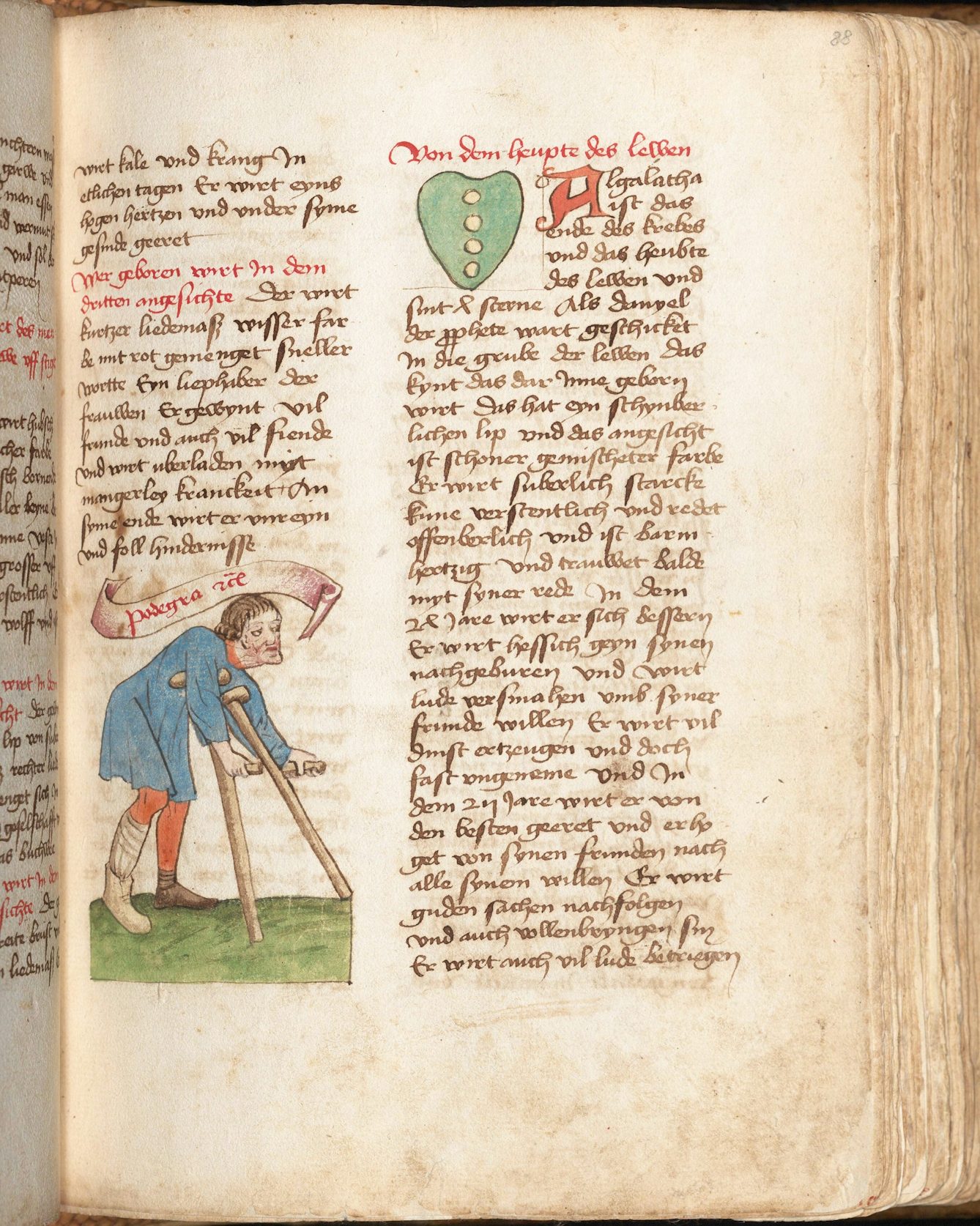

Many medieval manuscripts, even those that are not highly decorated, are filled with small sketches, designs and doodles made by the scribes who copied and produced them. This early 15th-century illustration is an example of such “medieval marginalia”. While medieval crutches were primary under-the-shoulder supports, the design of modern crutches depends on the user’s mobility and are made from steel tubes, to be adjustable for any variation in the person’s day-to-day mobility. Then as now, crutches could greatly increase a person’s mobility.

This illustration, from the German ‘Tübinger Hausbuch’, a book that combines medicine and astrology, dates from the 15th century and shows that the design of hand grips on crutches has varied little over time. These under-the-shoulder crutches with hand grips don’t look very different from their modern counterparts. A person’s crutches would be cut to length to suit them and could be recut should the individual’s needs change.

Hand trestles were another form of medieval mobility aid, with a modern parallel in the walking frame. The person shown in this 13th century manuscript clearly has either a natural variation or a dislocation in his lower limbs. He would have used the trestles to raise his upper body onto his hands and pull himself forward. The trestles would have been vital for his mobility, and an important possession, just as my own elbow crutches are to me.

This image, taken from the Luttrell Psalter, shows people with a range of mobility aids travelling to a shrine. Such illustrations are often found in the margins of works detailing miracles during the lives of the saints, or miraculous events at shrines. Some show an individual’s experience by depicting them arriving using aids and then leaving without their aids. In some cases, the healed person takes their aids with them as a sign both of their healing and a proof that they are the same person. This implies that their aids were a recognisable element of their identity – just as many people today customise their aids to reflect their personality. This sort of imagery was not restricted to manuscripts; some churches had Miracle Windows, for example Canterbury Cathedral.

This is me at Whitby in 2013. It was the first time I had been able to stand in the sea after a neurological incident in 2012 severely impaired my ability to walk. My elbow crutches take my weight on the hands and wrists, avoiding the problem of slippage associated with shoulder crutches. But there is still a risk of wrist and arm injuries from placing the weight solely on the hands. It’s a problem that would have been faced by people using crutches, trestles and walking frames across time. The design of crutches has changed little in 600 years, although one recent crutch design has attempted to solve the problem by dispersing the weight along the forearm rather than have it concentrated in the hands.

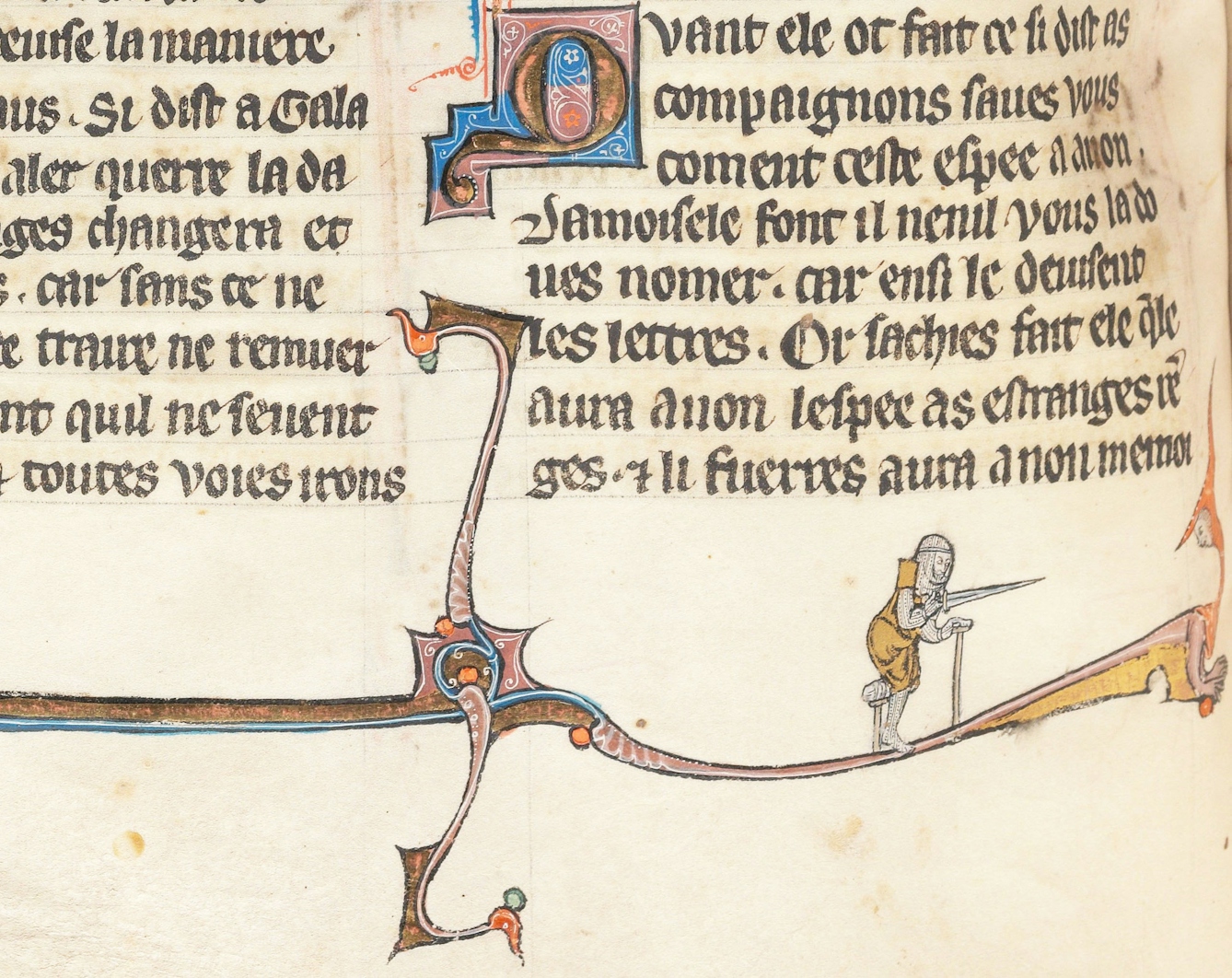

This illustration of a medieval knight attests to the concept of a prosthetic limb in the 13th century, although it is unlikely that a man-at-arms or knight would be able to fight on the ground with that combination of staff, sword and prosthetic. But some historical figures with impairments, such as John of Bohemia, continued to serve in combat – more commonly from horseback. The Knights of St Lazarus of Jerusalem, also known as the Leper Brothers of Jerusalem, had a military element during the mid-13th century, and some of their members were knights of other orders who had contracted leprosy and may have lost limbs as a result.

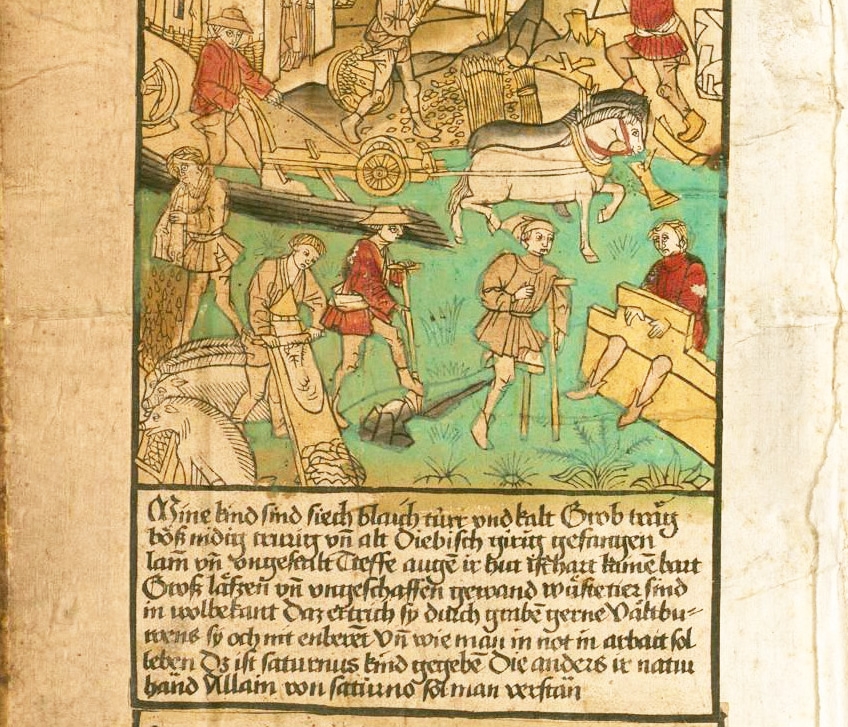

This manuscript of everyday rural life in 15th-century Germany contains a figure with the same type of prosthetic – a wooden support bound below the knee. The design of prosthetics, particularly for the lower limbs, had to be adapted to the individual’s requirements, ranging from the site of the amputation, the degree of healing, and the best way of securing the prosthetic to the person’s remaining limb.

This French book of hours contains an illustration of a man with a simple prosthetic limb like the fictional pirate’s ‘peg leg’. Such prosthetics would remain common from the Middle Ages through to the 18th and 19th centuries. Many of those who used them in the 15th century were veterans of numerous wars or had been injured in what we would now call industrial accidents. The bandages on the man’s other leg suggest that it was amputated below the knee more recently.

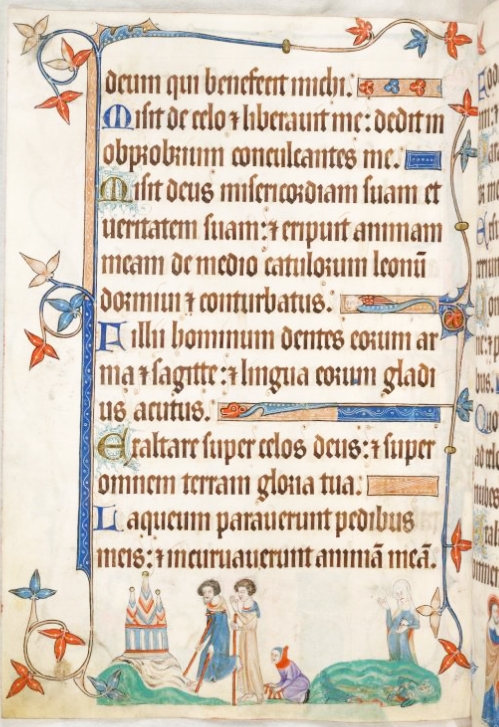

Fitting prosthetics would have been difficult, often involving arrangements of leather straps. The use of straps to secure aids goes back to the earliest surviving prosthetics, and it continues today. In this illustration, from a 15th-century book of psalms, we see a queue of men waiting to speak to a ‘horned’ Moses. The man at the front of the queue is using a similar prosthetic to the knight above, held in place with a binding below the knee. In medieval art, it was common to show historical scenes with people dressed in contemporary dress, as with the biblical figure of Moses. Many mobility-aid designs have changed little over time, which is hardly surprising, given that the human body itself remains largely unchanged. The materials may be different from the past, but the problems they were designed to solve, and the ingenuity behind them, is the same.

About the author

Jude Seal

Jude Seal is a PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London, researching the cultural perceptions of blindness, deafness and mutism in English miracle literature between 1070 and 1450. Their research explores the intersection of the histories of medicine and magic, and the archaeology of disease. They also write on living with a brain injury and chronic pain, and in their spare time are involved in disability sport.