Chemist Humphry Davy saw the experience of pain as a question of “mind over matter”. But his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge was intently tuned in to his own pain and the suppression of it with narcotics. Despite his no-nonsense views, Davy acknowledged that Coleridge’s introspective obsession with his body was part of his creative genius – one which put him ahead of the medical sensibilities of his day.

Coleridge’s hypochondria

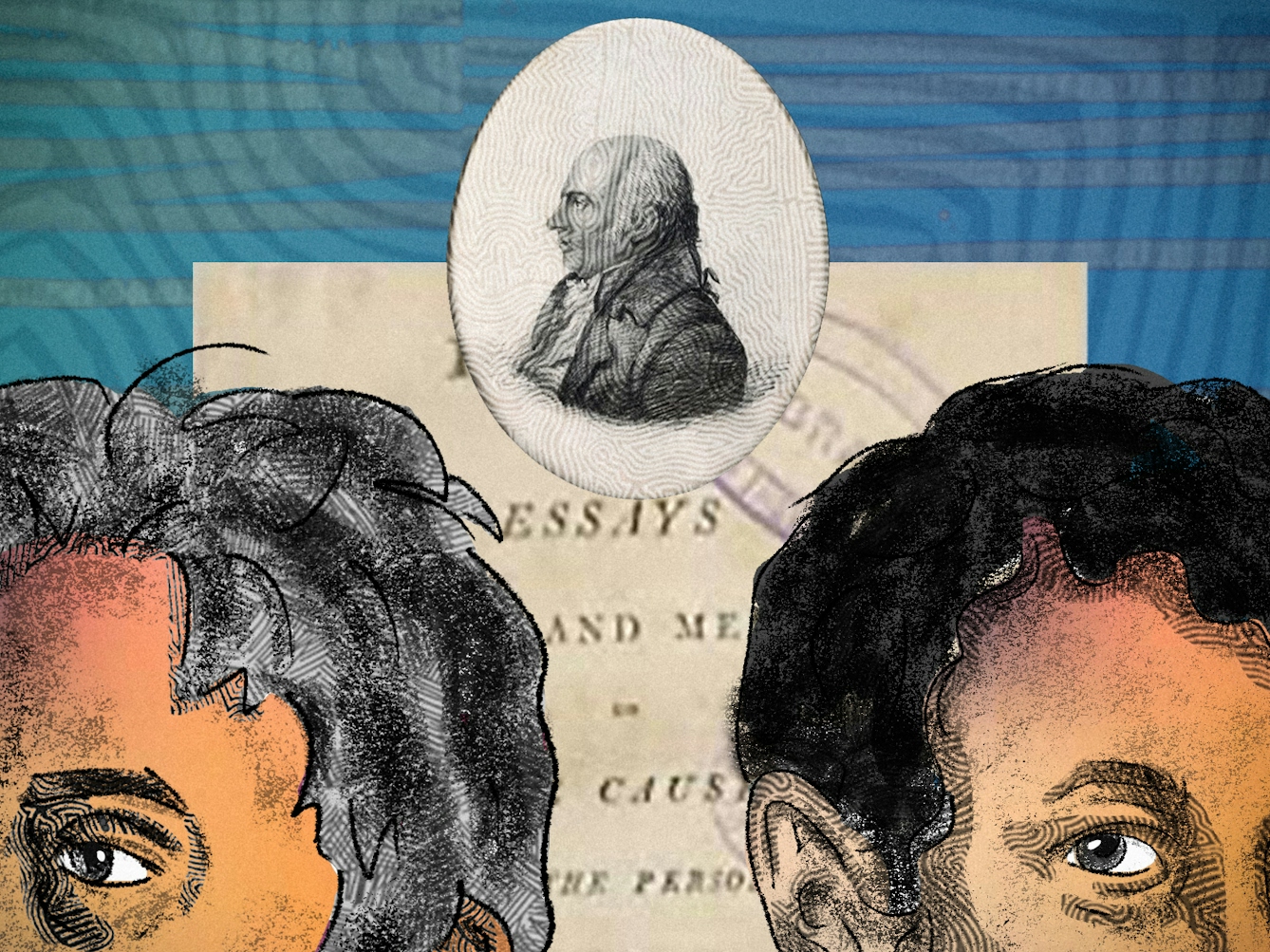

Words by Mike Jayartwork by Naki Narhaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Article

The poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the chemist Humphry Davy met as young men in Bristol in 1799 and quickly forged a friendship that would last a lifetime. Coleridge was fascinated by the chemical prodigy, who would in time become Sir Humphry, the great scientific genius of his generation.

“Living thoughts,” wrote Coleridge, “spring up like turf under his feet.” Davy was equally inspired by his new friend’s expansive notions of poetry and philosophy.

On one subject, however, they differed profoundly. For Davy, pain was a distraction; for Coleridge, a source of endless fascination. In one letter to his friend, Coleridge wrote: “I want to read something by somebody expressly on pain… it is a subject that exceedingly interests me.”

Davy maintained that “a firm mind might endure in silence any degree of pain”, and he relished any opportunity to demonstrate “the supremacy of mind over matter”. He was a fearless, often reckless experimenter: when he cut his finger to the bone in a laboratory accident, his first reaction was to dip it in a bottle of his newly discovered gas, nitrous oxide, and to note that the dripping blood turned purple.

In his report on nitrous oxide in 1800, Davy observed that inhaling the gas temporarily eased the pain of his laboratory injuries, and proposed that as it “appears capable of destroying physical pain, it may probably be used with great advantage during surgical operations”. But the suggestion, one among a handful of speculative applications, went no further.

“For Davy, pain was a distraction. He maintained that ‘a firm mind might endure in silence any degree of pain’, and he relished any opportunity to demonstrate ‘the supremacy of mind over matter’.”

Davy’s lack of interest in pain was matched by the surgeons of his generation, who dismissed anaesthetics as quackery that preyed on the patient’s fear of suffering. Medical orthodoxy was supported by the religious view that pain was a Divine necessity, and enduring it a moral test.

Diseases as signs of the times

Coleridge’s letters and notebooks, by contrast, are filled with minute observations of his rheumatism, boils, fevers, neuralgia and particularly his “treacherous bowels”, which inflicted on him an endless series of agonies. He would bury himself for hours in medical textbooks, and emerge with a self-diagnosis of kidney stones or bladder cancer.

The pair met through the radical physician Thomas Beddoes, who was Davy’s employer in Bristol in the search for therapeutic applications of gases, and Coleridge’s mentor in political activism and the latest medical theories. Beddoes was a pioneer of social medicine, and in his three-volume survey of the nation’s health, ‘Hygeia’ (1802), he identified hypochondria as a new type of occupational disease.

Coleridge would bury himself for hours in medical textbooks, and emerge with a self-diagnosis of kidney stones or bladder cancer.

Just as workers in industrial towns such as Birmingham were contracting lung diseases, he observed that hypochondria was becoming endemic among the “middling and affluent classes”. Medical fads and anxieties, encouraged by idleness, disposable income and predatory private doctors, blurred the lines between health and illness.

“The pair met through the radical physician Thomas Beddoes, who recorded the rise of hypochondria in his own practice.”

Excessive attention to minor symptoms created negative feedback loops that could turn slight breathlessness into alarming chest pains, or (as with Coleridge) a bout of indigestion into weeks of infirmity.

Beddoes recorded the rise of hypochondria in his own practice and found himself prescribing more narcotic drugs such as opium and ether: palliatives that were effective at reducing anxiety but compounded the condition if their use became habitual.

This was precisely what befell Coleridge. He kept his opium habit a secret for years, and when this was no longer possible, he pleaded medical necessity. Many of his friends had their doubts, notably his former secretary Thomas De Quincey, who judged that Coleridge’s opium use was a “surreptitious seeking for pleasure”: despite his protestations of illness, he was not medicating pain but merely the ennui we must all endure as part of the human condition.

Opium gave Coleridge immediate relief, but it extracted a terrible price. It could give him a radiant glow and wonderful fluency at the dinner table, but these raptures were followed by the insomnia and skin-crawling hypersensitivity he describes in poems such as ‘The Pains of Sleep’ (1803), and the torments of constipation, a shameful metaphor for the writer’s block that opium also induced.

Coleridge was all too aware of the judgements being passed on him, yet he dwelt deeply on his pains, their causes and their meanings, and particularly their effects on his mental world. “My spirits are low,” he wrote to a friend in 1804, “but this I well know is a symptom of bodily disease, and no part of sentiment or intellect.”

“Imagination was the key to Coleridge’s philosophy… he loved to invent words, and the term he coined for the connections between mind and body was an enduring one: ‘psycho-somatic’.”

The fashion for compassion

Imagination was the key to Coleridge’s philosophy, the link between mind and matter, and interrogating his bodily constitution was inseparable from his creative life. As Humphry Davy wrote in 1808, when his invitation to Coleridge to lecture at the Royal Institution provoked a nervous collapse, the poet’s “excessive sensibility” was “the disease of genius”. Coleridge loved to invent words, and the term he coined for the connections between mind and body was an enduring one: “psycho-somatic”.

As the 19th century advanced, Coleridge’s interest in pain and illness became more in tune with the times. “Sensibility” – what we might today call empathy or compassion – was increasingly valued as a mark of character. A progressive “middling class” led campaigns against displays of cruelty and suffering, from bear-baiting to Bedlam visits to public executions.

The “language of feeling” explored by Davy and Coleridge’s generation of Romantic poets bore fruit in the popular novel, in which authors such as Charles Dickens invited their readers to share the suffering experienced by the less fortunate. Some physicians and religious authorities continued to argue that pain was a necessity, but for many it had come to seem barbaric to withhold analgesics such as ether and opium from patients, especially those suffering chronic or terminal illness.

Fifty years after Davy’s and Beddoes’ experiments, nitrous oxide and ether finally found the defining medical application for which they had been searching: anaesthesia. British surgeons were initially reluctant to adopt the newfangled American discovery – a “Yankee dodge” – but public opinion tipped in its favour when Queen Victoria was administered chloroform in 1853 during the birth of her eighth child, Leopold. She pronounced the experience “delightful beyond measure”.

By this point, to inflict pain needlessly seemed reprehensible, and anaesthesia was hailed as the medical discovery of the century. Coleridge had died in 1834, a gentleman invalid fondly remembered by the staff of T H Dunn’s pharmacy on Highgate Hill, which he visited for his regular supply of opium tincture.

But in this new climate, his “hypochondriac delights” – his biographer Richard Holmes’s perceptive phrase – appear not simply as a moral flaw, but a prescient injunction to pay more attention to our embodied selves.

About the contributors

Mike Jay

Mike Jay is an author and curator who has written widely about the history of science and medicine. He has co-curated two exhibitions with Wellcome Collection: ‘High Society: mind-altering drugs in history and culture’ (2010–11) and ‘Bedlam: the asylum and beyond’ (2016–17). His book ‘The Atmosphere of Heaven’ (2009) tells the story of Thomas Beddoes, Humphry Davy and the discovery of nitrous oxide. His most recent book, ‘Mescaline: a global history of the first psychedelic’ (2019), is out now in paperback.

Naki Narh

Naki is an artist of Ghanaian descent from two homes, Accra and London. Her work draws inspiration from quintessentially Ghanaian tropes and concerns: explorations of self and identity, social and personal conscience. She loves to work with abstract lines, portraits, colour and patterns. She works in ink and acrylic on paper, digital painting and canvas. Explosions of colour and patterns mark her rapidly evolving signature style. Her love for art and architecture are more than expressions of self: they represent an amalgam of all that has moulded her themes and style of painting. They are an assimilation of the kaleidoscope of cultural and structural vibrancy and vitality of a life spent immersed in distinctly different cultures.