For many of us, this has been a year with very little physical human contact. Historian Agnese Reginaldo explores the fundamental importance of touch to human health, and the adaptations we have made to keep ourselves safe.

Hugging, kissing, shaking hands, or touching someone while having a conversation are everyday interactions that are now heavily restricted, and in many cases forbidden.

The way we physically and mentally relate to others has changed remarkably due to Covid-19. The two-metre distance that separates us from each other may increase our safety and reflect social responsibility, but humans are not designed for a world where our interactions are devoid of touch. We are now accustomed to living in an environment where physical contact is dangerous, but what effect could this have on people?

Touch is the first of our senses to form. It develops before birth, at around eight weeks, beginning mainly with the most sensitive areas, including the lips and nose. Touch is an essential instrument for children to explore and learn, and the main way their parents communicate and interact with them in the weeks after birth.

It is also a primary biological necessity, and having to abstain from touch can lead to affection deprivation, or ‘skin hunger’, which has significant consequences for mood and general health. Being touched stimulates pressure sensors, sending information to the brain that automatically relaxes the nervous system, slows down the heartbeat and lowers blood pressure.

“The two-metre distance that separates us from each other may increase our safety and reflect social responsibility, but humans are not designed for a world devoid of touch.”

Touch in the form of grooming also has a significant role to play in social cohesion, as British anthropologist and psychologist Robin Dunbar has discovered. Dunbar studied how grooming in primates – including humans – is used for bonding. Monkeys that groomed each other were more likely to work as a team and defend others when faced with danger than those who abstained from grooming.

Reaching out and hugging for at least 20 seconds releases endorphins and serotonin in the body, relieving pain and anxiety.

Oxytocin, sometimes known as the ‘love’ hormone, is a chemical we release during breastfeeding, and also when we hug, touch or kiss someone. It has an astonishing effect on our mental and physical health, reducing levels of cortisol back to normal after a stress response, as well as helping us to improve our relationships.

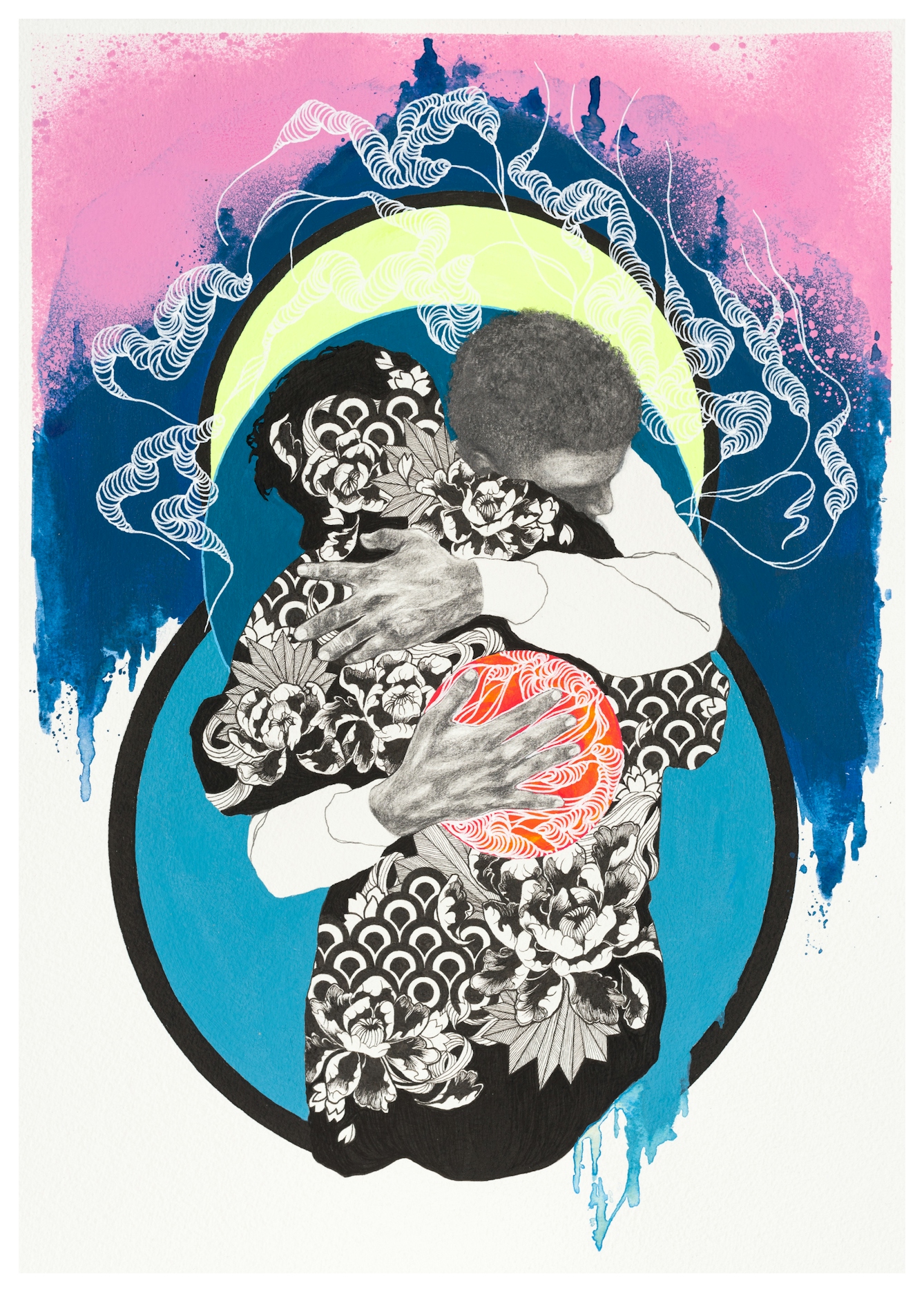

Research has shown that hugging is especially important, and that it could even reduce the likelihood of death from heart disease. Reaching out and hugging for at least 20 seconds releases endorphins and serotonin in the body, relieving pain and anxiety. During the Covid-19 pandemic, a time in which we need more than ever to relax, reduce stress and boost our immune system, it seems ironic that we should be deprived of hugging in order to protect our health.

“Oxytocin, known as the ‘love’ hormone, is a chemical we release during breastfeeding, and also when we hug, touch or kiss someone.”

A world of hands-free hugs

Today’s governments are merely the most recent in a long line of rulers banning close contact when faced with the rapid spread of disease. The formal kiss of greeting has fluctuated in popularity, disappearing in France during a 14th-century outbreak of plague, and remaining unpopular for centuries.

In England in 1439, the teenage King Henry VI also responded to the threat of plague by banning kissing. This was of course hundreds of years before people understood the real reasons for the spread of infectious diseases, although proximity to a sick person was recognised as dangerous. The ban was probably to protect Henry himself from the ritual of people kissing his ring in greeting.

In the UK, the formal kiss was long ago replaced by a handshake, which in turn has been recently ousted by the elbow bump. But replacing the hug is trickier.

In May 2020, at the height of the pandemic, various techniques and tools around the world were proposed to avert the dangers posed by hugging. ‘Hug gloves’ – a clear plastic sheet with sleeves to facilitate hugging with no skin contact– have been tried out in Canada and the UK, and aerosol scientists have been induced give instructions on how to hug safely, including holding your breath while hugging, and directing your face away from the other person.

“During the Covid-19 pandemic, a time in which we need more than ever to relax and boost our immune system, it seems ironic that we should be deprived of hugging in order to protect our health.”

During times when lockdown rules were loosened, it felt odd meeting friends and family without opening our arms to greet them, or being introduced to a stranger and not shaking hands. “Should I be closer or further away from them? Is the person in front of me expecting some physical contact or not? If so, what is appropriate?”

Video calls with family and friends are helping us to survive this distance, but these tools cannot deliver the inherent warmth of a hug, and can easily make us feel that personal connections are harder to establish.

We need to verbalise a lot more than when the language of touch was part of our communication arsenal. If someone is experiencing physical pain or feeling anxious, it is much more natural to reach out and hold their hand instead of finding the right words to express our consolation and support.

Perhaps such adaptations will help us all become better communicators, but until then we can only hope that with the promised “return to normality” later this year, we will all be able to hug our loved ones again soon without fear or danger.

About the contributors

Agnese Reginaldo

Agnese Reginaldo is an art historian whose work focuses on the intersection between art and social sciences. Her practice focuses on public-engagement projects aiming to create a more effective connection between the public and contemporary art in museum and gallery settings.

Aisha Young

Aisha is a Kent-based artist using drawing and painting to create works that explore the everyday chaos that resides in the mind, unspoken emotions and the sometimes unseen stories that play out daily. She draws and paints in a realistic style that's then combined with layers of colour, pattern and texture. She plays with real and surreal elements in her work, celebrating the oddities and irregularities that can occur with an erratic thought process.